Was Commodus Truly the Megalomaniac Gladiator Emperor?

Commodus was largely seen as capricious, self-indulgent, and more interested in personal pleasures than in governing the empire.

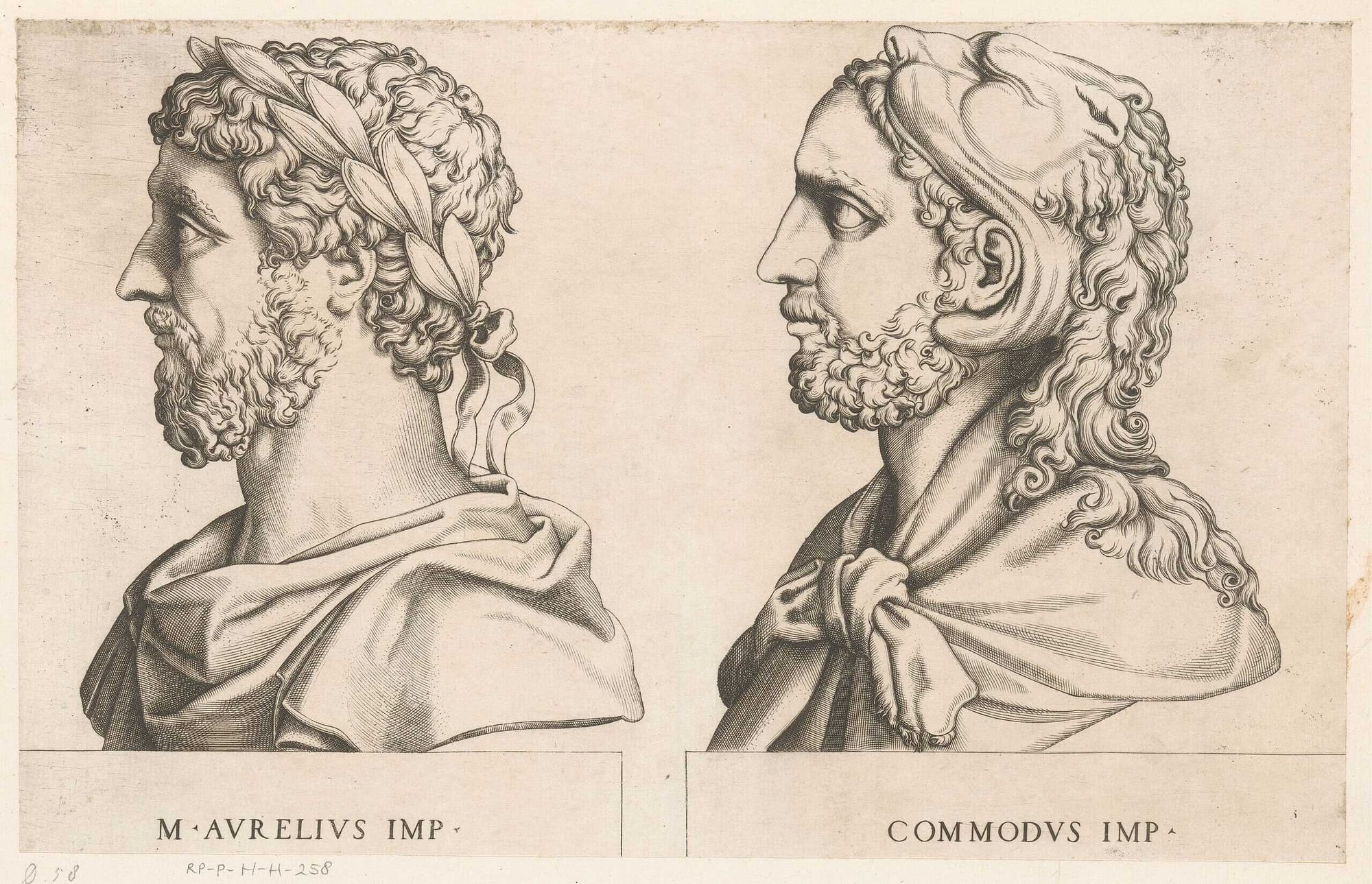

Commodus (Lucius Aurelius Commodus) was Roman emperor from 180 to 192 AD and is often remembered for his erratic behavior, his love for gladiatorial combat, and the decline of Rome during his reign. He was the son of the highly respected Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and his reign marked the end of the "Five Good Emperors" and the beginning of the empire’s decline into instability.

The Portrait of a Bad Emperor

In most ancient and modern literature, the Roman emperor Commodus, is portrayed in overly simplistic and highly negative terms. He is often depicted as a madman, megalomaniac, foolish, and immoral, with seemingly no redeeming traits. While Commodus was undoubtedly a more complex individual, the real person has been lost to history, having lived nearly two thousand years ago.

Today, Commodus survives mainly as a literary figure, shaped by narratives created by others. This character, who embodies the antithesis of a good ruler, dates back to the earliest surviving accounts of him from the early third century and continues to influence modern historiography.

The central question is: what factors have contributed to the negative portrayal of Commodus in both Roman and modern historiography? To answer this, we must explore related questions: what led to the creation of this narrative? Why does the depiction of Commodus as a bad emperor resonate with both historians and readers? Are there alternative representations of him, and why have these been overshadowed by the dominant literary narrative?

It's important to consider not only historiography but also literature and fiction, as the relationship between these fields helps explain the development and persistence of the character of Commodus. This is particularly significant when examining the broader narrative of "good" versus "bad" emperors. (The Literary Character of the Roman Emperor Commodus, by Ingjerd Arnøy)

Commodus’ Heritage; a Heavy Burden

Commodus ruled as emperor for thirteen years, a reign of such length that it suggests he could not have been all the negative things he is often depicted as, and still survived. It was a turbulent period in Roman history, as Commodus grappled with crises inherited from his renowned father, Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor.

The Roman Empire was plagued by a devastating epidemic that decimated armies and emptied cities, while years of continuous warfare had left large portions of the empire ravaged, straining its finances to the breaking point. According to the historian Cassius Dio, Commodus inherited a "kingdom of gold" and left it one of "iron and rust," but this narrative challenges that view, which many historians and filmmakers have uncritically accepted.

Faced with a fragile political system and a collapsing financial structure that benefited a small aristocratic elite, Commodus sought to reform the empire. He aimed to create an autocratic monarchy supported by a professional class of imperial freedmen and officials, rather than relying on the increasingly disloyal and self-serving senatorial aristocracy. Deprived of their privileges, gifts, and promotions, a small group of elite families conspired against Commodus, the very man they publicly praised while secretly plotting his death.

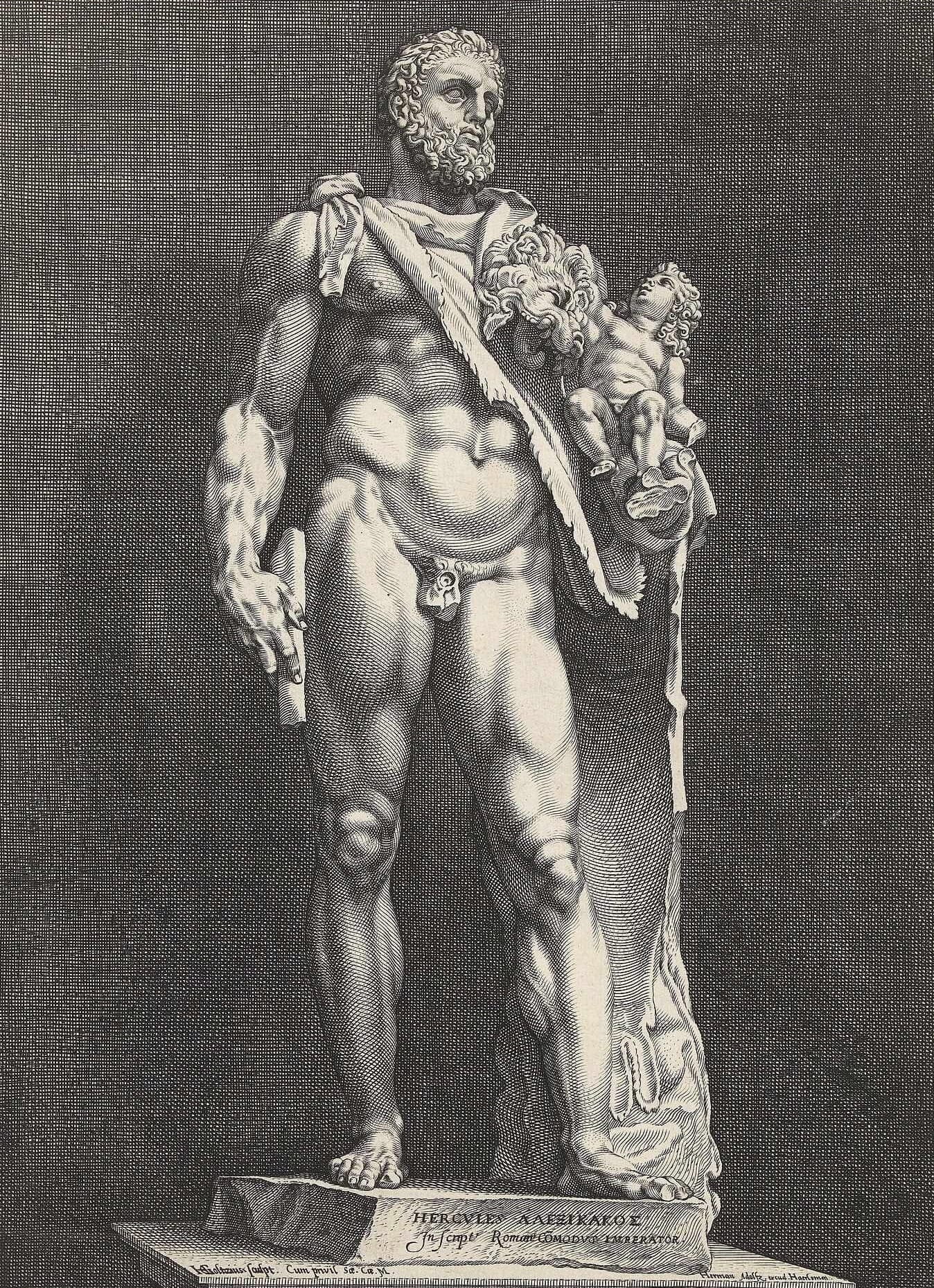

Commodus rejected the republican values that Augustus had concealed behind his imperial rule. Instead, Commodus saw himself as a supreme patron ruling for the good of all. He identified with the demigod Hercules, a figure known for his physical strength, hunting ability, and survival against deadly odds.

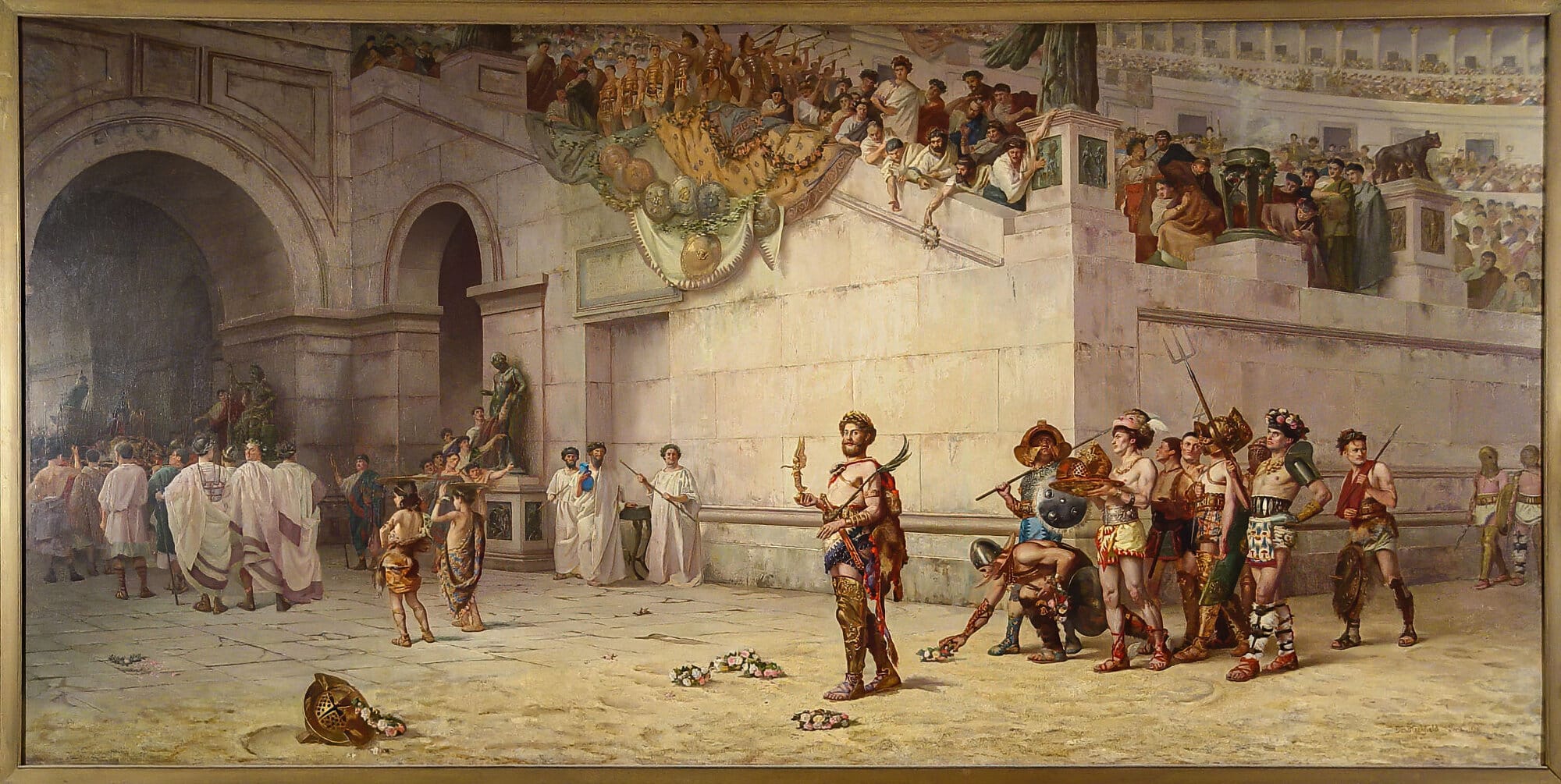

By fighting as a gladiator, Commodus expressed empathy with the resilience of mankind in an era of chaos and deadly plague. To the Romans who chanted his name in the Colosseum, Commodus had transcended mortality to become their "Roman Hercules," fighting to preserve the empire and create a new golden age.

The Roman populace largely embraced this image, especially after Commodus had virtually rebuilt the city following a destructive fire. However, a small elite group of aristocrats resented the threat to their power and influence, recalling their privileged "golden age" under Marcus Aurelius. To justify their assassination of his son, they painted Commodus as a madman, a tyrant, and a debauchee.

The result? Nearly a century of barbarian invasions, civil wars, and the very transformation of the empire into the system that Commodus had attempted to create.

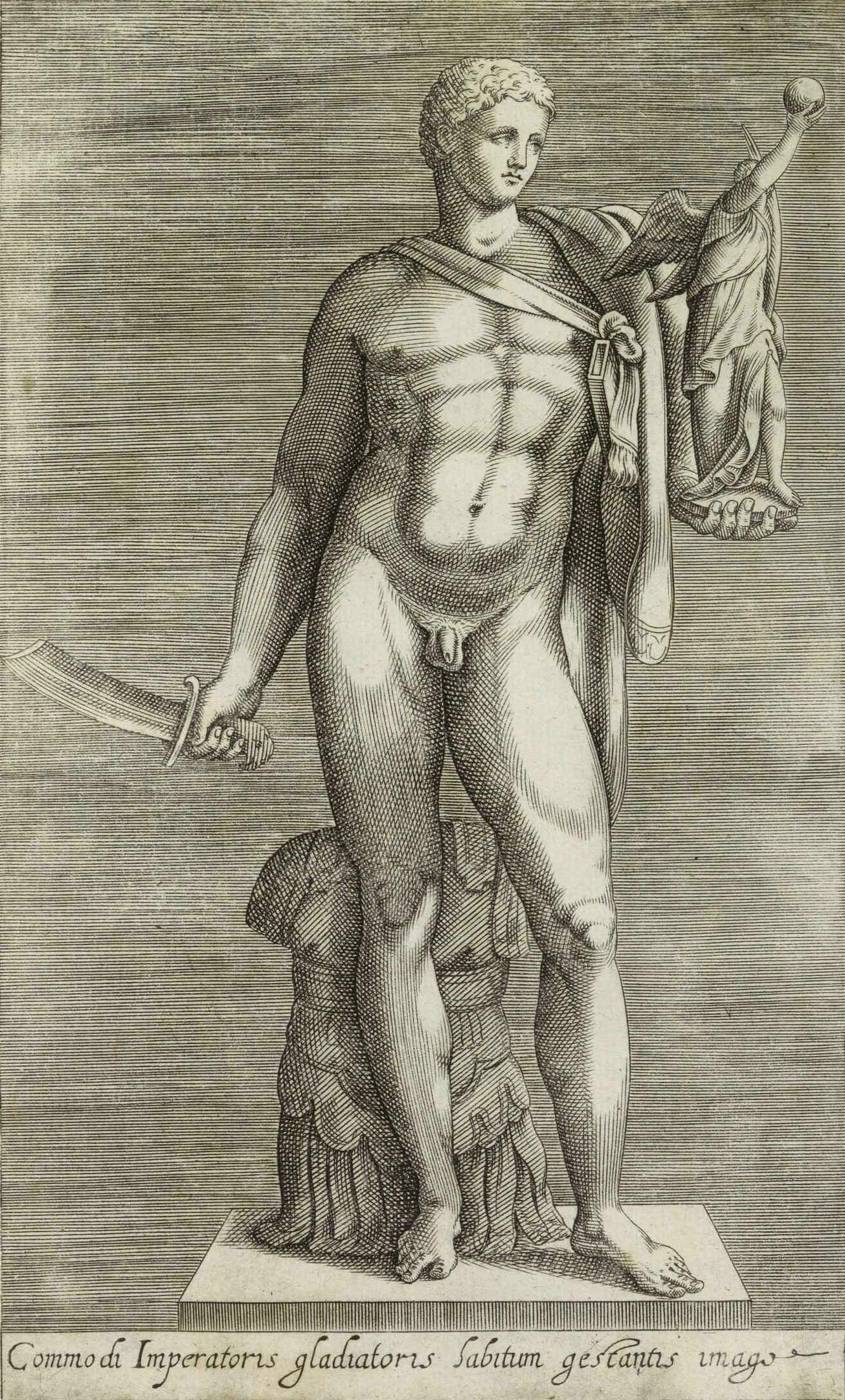

Commodus’ bust as Hercules, engraving by unknown artist. Public domain

Historians and publishers have largely concentrated on Commodus' father and predecessor, Marcus Aurelius, as well as his eventual successor, Septimius Severus. As a result, the significant reign of Commodus, which marked a pivotal moment in Roman history, has been almost entirely overlooked.

A Misty Background

By the time Commodus became emperor, the Roman Empire had enjoyed a prolonged period of political stability. Following the assassination of Domitian in 96 AD, the Senate chose Nerva as emperor, though his reign was short due to his age and lack of support from the army and Praetorian Guard.

Nerva adopted Trajan as his heir, establishing a trend where emperors were adopted by their predecessors due to a lack of male heirs rather than a deliberate policy. This adoption practice, rooted in Roman law, was not new; Julius Caesar had adopted Augustus, and Augustus later adopted Tiberius.

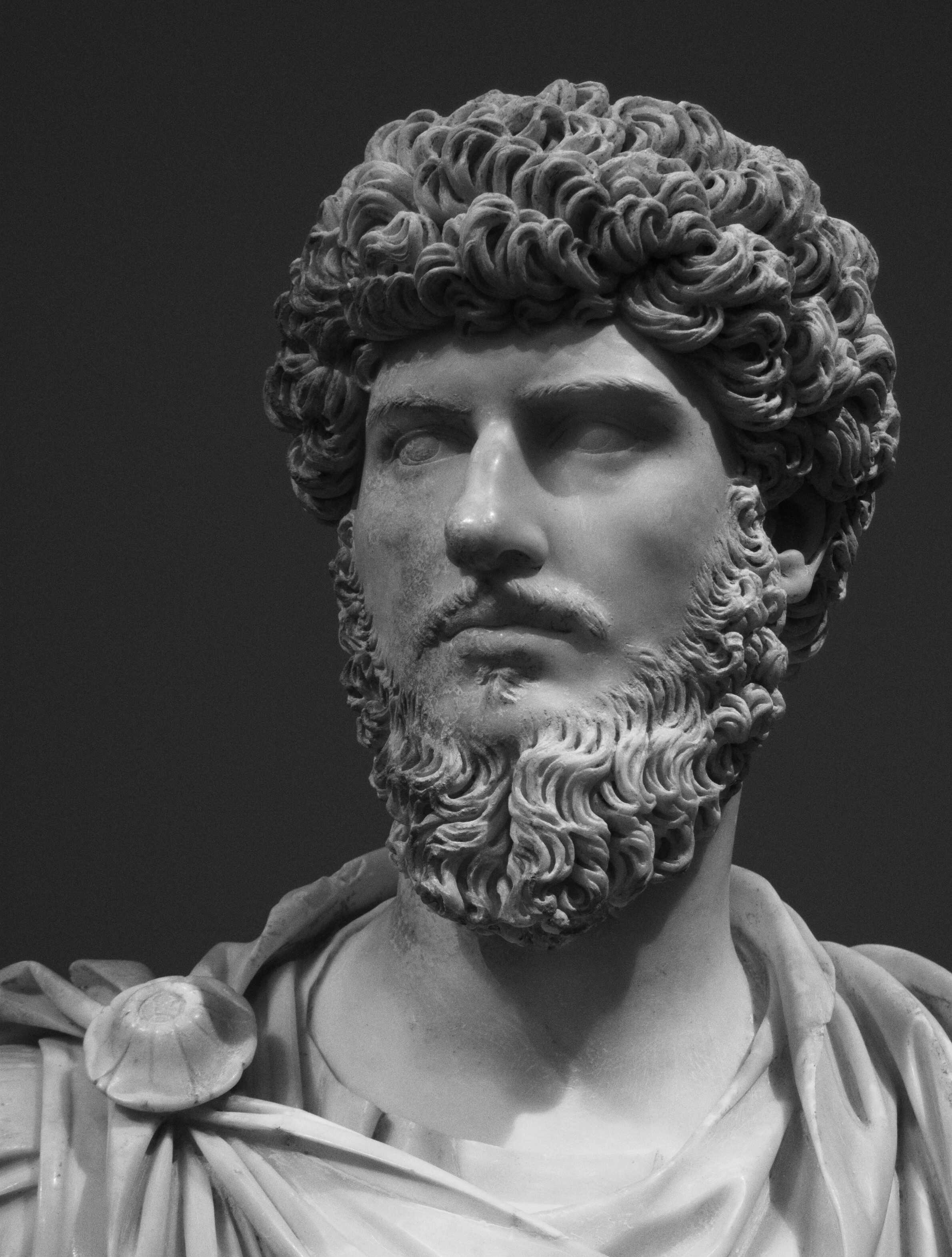

Commodus’ father, Marcus Aurelius, ascended the throne in 161 AD alongside Lucius Verus, who had been adopted by Emperor Antoninus Pius. Their joint rule was strengthened by the marriage of Verus to Marcus Aurelius' daughter, Lucilla, while Marcus had been married to Faustina, the daughter of Antoninus Pius.

However, the empire’s peace was shattered by two major events: a plague and barbarian invasions beginning around 166 or 167 AD.

Painting of Commodus by Rubens, as Hercules. Credits: Leiden Collection, Public domain

Known as the ‘Antonine Plague,’ the disease was brought into the empire by soldiers returning from campaigns in the East. Lucius Verus, while not seen as either a great or terrible emperor, lived a luxurious lifestyle away from the plague-ridden streets of Rome, building a palace on the city's outskirts. His death, likely from the plague, led Marcus Aurelius to remarry Verus’ widow, Lucilla, to a man of lower status, Claudius Pompeianus, which caused tension within the family.

Meanwhile, Marcus Aurelius focused on repelling barbarian invasions along the Danube frontier, facing a string of military and financial challenges. The empire was strained by continuous warfare and the plague, which depleted both armies and the imperial treasury.

Despite the chaos, Marcus Aurelius sought to stabilize the empire by promoting skilled military commanders like Pompeianus and Pertinax, and relying on his network of senatorial allies. The empire faced unrelenting war, barbarian invasions, and even a rebellion led by Avidius Cassius in the East. The widespread devastation, plague, and civil unrest left much of the empire in ruins by the time Marcus Aurelius died in 180 AD.

Commodus inherited this troubled kingdom, which had been significantly weakened despite its outward appearance of stability and prosperity. The idea of the empire being a "kingdom of gold" during Marcus Aurelius' reign, as later historians suggested, contrasts with the reality of the significant challenges Commodus faced when he became emperor. (The emperor Commodus god and gladiator, by John S. McHugh)

Commodus According to Historical Tradition

According to the most well-known ancient sources, which reflect the hostile perspective of Rome's senatorial aristocracy, it is difficult to imagine a worse ruler than Commodus. Even before his birth, his mother Faustina was troubled by ominous warning dreams, and his early childhood was marked by the tragic loss of his twin brother:

“Faustina, when pregnant with Commodus and his brother, dreamed that she gave birth to serpents, one of which, however, was fiercer than the other.

But after she had given birth to Commodus and Antoninus, the latter, for whom the astrologers had cast a horoscope as favourable as that of Commodus, lived to be only four years old.”

Augustan History: Commodus 1.3–4; quoted from David Magie (tr.), The Scriptores Historiae Augustae

Although Commodus' father had entrusted him to the care of excellent teachers, the young prince's true character emerged during his adolescence, as he became corrupt, shameless, and inclined toward debauchery. His moral decline was so severe that, once he became emperor, he quickly signed disadvantageous peace treaties with the enemies his father had defeated, allowing him to indulge in his dark pleasures.

"He abandoned the war his father had nearly completed and accepted the enemy's terms, then returned to Rome."

Some courtiers, supported by Commodus' sister Lucilla, conspired against him, but the failed plot led to brutal reprisals, particularly targeting the aristocracy. Lucilla was exiled; following this, Commodus appointed Tigidius Perennis as prefect of the guard, giving him sole control over the empire, while Commodus continued his reckless, indulgent lifestyle.

“Perennis, being well acquainted with Commodus’ character, discovered the way to make himself powerful, namely, by persuading Commodus to devote himself to pleasure while he, Perennis, assumed all the burdens of the government – an arrangement which Commodus joyfully accepted.

Under this agreement, then, Commodus lived, rioting in the Palace amid banquets and in baths along with 300 concubines, gathered together for their beauty and chosen from both matrons and harlots, and with minions, also 300 in number, whom he had collected by force and by purchase indiscriminately from the common people and the nobles solely on the basis of bodily beauty.”

Augustan History

Commodus' excessive fascination with gladiatorial games drove him to personally participate in these combats, frequently endangering the lives of his courtiers. Ultimately, he even ordered the execution of his sister.

“He fought in the arena with foils, but sometimes, with his chamberlains acting as gladiators, with sharpened swords.

By this time Perennis had secured all the power for himself.

He slew whomsoever he wished to slay, plundered a great number, violated every law, and put all the booty into his own pocket.

Commodus, for his part, killed his sister Lucilla, after banishing her to Capri.”

Augustan History

Commodus’ delusions of grandeur reached new heights when he began to rename things in his own honor. He officially renamed Rome itself as Colonia Commodiana (“Colony of Commodus”) and referred to the Roman people as Commodiani. He even changed the names of the months to reflect his many titles, such as Lucius, Aurelius, and Commodus.

Additionally, statues were erected of Commodus dressed as Hercules, complete with a lion's skin and club. He proclaimed himself as Hercules reincarnated, often appearing in public as the demigod and even having coins minted with his image as Hercules.

In the hostile and bitter portrayal provided by the Augustan History, Commodus embodies all the classic stereotypes long associated with tyrants, which have been recognizable in historical accounts of despotic rulers dating back to archaic Greece. These familiar tropes include a dream warning the tyrant's mother during pregnancy, childhood marred by family losses, abnormal or bizarre sexual behavior, a violent nature, and a tendency to persecute and humiliate the aristocracy.

Naturally, these accounts culminate in a horrific and exemplary death.

The biographers or historians who depict tyrants in this way intended their deaths to serve as warnings, deterring future generations of power-hungry men from autocratic ambitions. The particularly striking detail about Commodus’ harem of concubines and male lovers, numbering three hundred, was an attempt to commemorate the legendary heroes of Thermopylae.

Commodus gathered them through a combination of money and force, the latter especially among the aristocracy. This recalls the so-called "Flowers of Samos," a group of male and female beauties assembled for the tyrant Polycrates' pleasure, as well as the island location of Laure, a sort of red-light district where courtesans were kept in lush gardens surrounded by luxuries for the tyrant's enjoyment.

In contrast to the exaggerated depiction of Commodus in the Augustan History, Cassius Dio's account is somewhat more lenient, though it still includes many vivid, sensational, and at times gruesome details. Dio primarily attributes Commodus' negative traits to the influence of bad companions.

“This man [Commodus] was not naturally wicked, but, on the contrary, as guileless as any man that ever lived.

His great simplicity, however, together with his cowardice, made him the slave of his companions, and it was through them that he at first, out of ignorance, missed the better life and then was led on into lustful and cruel habits, which soon became second nature.”

Rather than emphasizing Commodus' perversions and sexual peculiarities, the historian chooses to focus more on his violent tendencies and his involvement in gladiatorial activities:

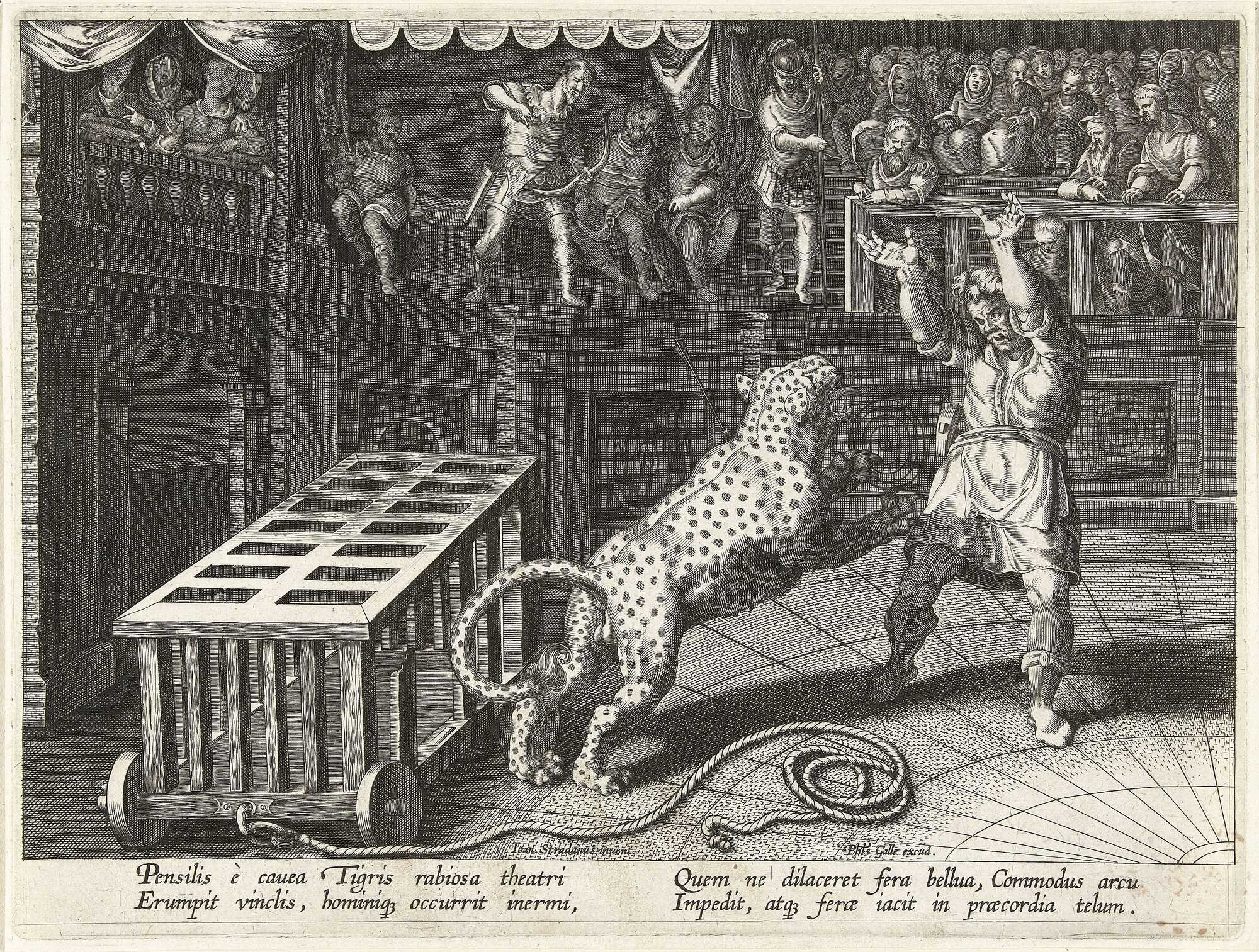

“Commodus devoted most of his life to ease and to horses and to combats of wild beasts and of men.

In fact, besides all that he did in private, he often slew in public large numbers of men and beasts as well.

For example, all alone with his own hands, he dispatched five hippopotami together with two elephants on two successive days; and he also killed rhinoceroses and a camelopard [giraffe].

This is what I have to say with reference to his career as a whole.”

Dio portrays Commodus' unusually intense enthusiasm for gladiatorial combat as simply an eccentric aspect of his personality. However, it is possible to infer that the emperor's appearances in the arena were part of a deliberate strategy to win the favor of the urban masses, rather than a simple symptom of megalomania. In most cases, Commodus‘ character was condemned — and even suffered damnatio memoriae, since there is visible evidence that figures of his likeness were removed from the Constantine Arch, at the orders of an unknown emperor.

Was Commodus Really that Bad?

Barry Baldwin, a scholar who has examined the controversial emperor Commodus, begins his analysis with a discussion of a debated passage by the late fifth-century AD Carthaginian poet Blossius Aemilius Dracontius. In his work Satisfactio, written to placate the Vandal king Guntamund, Dracontius initially praises Julius Caesar, Augustus, and Titus. However, unexpectedly, he also begins to praise Commodus, with lines 187–190 being particularly surprising:

“The other emperor, Commodus Augustus, a poet and a good man with a sense of duty and devotion, says in a modest little discourse: “A noble precept, rulers [or: teachers], learn from me: he who wants to be a god should lead a responsible life.”

While some scholars suggest that Dracontius made a significant error by confusing Commodus with his father, the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius, Barry Baldwin argues that such a mistake would be unlikely for a poet who typically demonstrated historical accuracy.

Baldwin believes that the moralizing lines in Satisfactio do indeed refer to Commodus. He points out that any well-educated Roman citizen, especially a young prince like Commodus, would have been capable of composing such lines, and even a ruler known for immoral behavior could invoke noble sentiments when it suited him, similar to how Nero did.

What remains harder to explain is Dracontius' praise for Commodus' moral character. Baldwin suggests that the two lines Dracontius references may date back to Commodus' youth, although the phrase vir bonus typically refers to an adult. Baldwin notes that, while the Augustan History presents an especially negative portrayal of Commodus, even Cassius Dio and Herodian acknowledge some of his good qualities; with the latter praising the emperor’s beauty, as Michael Grant illustrates in his book, The Roman Emperors.

Scholars like Baldwin argue that Dracontius’ positive view of Commodus likely stems from the favorable treatment Africa received under his rule. Perspectives from places like Antioch and Carthage differed from those in Rome. Additionally, Baldwin suggests that the divergence in judgments on Roman emperors in later ancient and Byzantine sources, compared to earlier historians, may be influenced by Christianity. (Was Commodus really that bad?, by Eleonora Cavallini, in The Fall of the Roman Empire, film & history, edited by Martin M. Winkler)

The Death of Commodus

The senators and noblemen, who stood to gain the most from Commodus' death, were too fearful to make an attempt on his life. While the people may have been wary of his cruelty, they appreciated the extravagant games he hosted and the generous gifts he distributed to keep them content. They had no desire to kill him.

Thus, the conspiracy that eventually led to his death emerged from an unlikely source.

Roman Athlete Narcissus strangling Emperor Commodus, engraving by G. Mochetti. Credits: Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0

After killing his wife Crispina, Commodus took several mistresses, but his favorite was a freed slave named Marcia, whom he treated as his wife, granting her many privileges an empress would enjoy. Two other key figures in his circle were his chamberlain Eclectus and the guard prefect Laetus, responsible for his personal safety. Remarkably, it was these three—Marcia, Eclectus, and Laetus—who conspired to bring about Commodus' demise.

Commodus was murdered on New Year's night in A.D. 192. According to the story, he had planned to dress as a gladiator the following day to "open" the new year by parading around with gladiators. Laetus and Eclectus reportedly advised him to wear the imperial purple instead, as it was more dignified. Marcia supported their suggestion.

Enraged, Commodus withdrew to his room and wrote orders for their execution, along with the execution of several others. A young boy, who was particularly dear to Commodus and allowed to roam freely in the palace, found the notebook with the orders and started playing with it.

The boy walked along the corridor. By coincidence the boy happened to meet Marcia, who was also very fond of him.

She gave him a hug and a kiss, and then took the tablet from him because she was afraid that he might destroy something important by mistake while innocently playing with it.

But when she realized that it was Commodus' writing, she became curious to have a look at the contents.

Finding that it was a death-warrant, and that she was going to be first to be executed, with Laetus and Eclectus next, and similar deaths awaiting the others, she let out a scream."

Marcia quickly informed Laetus and Eclectus, and together they decided to kill Commodus before he could carry out their executions. Since Marcia always prepared Commodus' drinks, they chose poisoning as the easiest method. Commodus drank the poisoned wine without any suspicion.

However, because he was so intoxicated, he vomited, and the poison did not take full effect—it only made him very drowsy. As a result, the conspirators sent in Narcissus, a powerful athlete, who strangled Commodus while he was still unconscious from the effects of the wine and poison.

Commodus died at the age of thirty-one, having ruled as sole emperor for thirteen years. (Commodus: Rome's third maddest emperor, by Hekster, O.J)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: