Vestal Virgins: Keepers of Rome's Eternal Flame and Protectors of the State

The Vestal Virgins were guarding Rome’s sacred flame keeping the state safe.

The Vestal Virgins were a group of priestesses in ancient Rome dedicated to the goddess Vesta, the deity of the hearth, home, and family. Their primary duty was to maintain the sacred fire within the Temple of Vesta, which was not allowed to go out as it symbolized the security and eternal life of Rome.

Who was Vesta?

Vesta, the titular deity of the Vestal Virgins and one of Rome's most esteemed deities, was the goddess of the hearth in every Roman home as well as the protective deity of the symbolic hearth of the Roman state—the eternal fire within Vesta's temple. Her cult was both domestic and civic. Her Greek counterpart was Hestia, whose name means "hearth."

Vesta was associated with agricultural fertility, and the fire she embodied had regenerative powers. Fields were burned to fertilize them for the next crop, reflecting Vesta's procreative power of the flame. Among the treasures in the Temple of Vesta was a phallus (fascinus). This minor deity, Fascinus, was symbolized by a phallus, and phallic amulets, known as fascini, were used by the Vestals (among others) to ward off evil.

The virginity of the Vestal priestesses complemented the procreative power of the goddess Vesta, symbolized by the fire that purifies and regenerates the earth through destruction. For much of her history, Vesta was aniconic, meaning she had no recognizable form or gender. However, during the imperial era, Vesta's gender was defined and controlled by depicting her as a matron. In coin and relief sculptures, Vesta was shown wearing the stola, transforming her powerful natural force into a domesticated Roman matron.

Vesta's physical representation became increasingly important in imperial coinage around the same time that portraits and honorific statues of the Vestals began appearing in the Atrium Vestae. (Molly Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, Priestesses of Ancient Rome)

Who were the Vestal Virgins?

The Vestal Virgins were unique among public priesthoods. Selected before puberty from various eligible candidates, they were freed from all legal obligations and ties to their birth families. They joined Vesta's priestly college, which consisted of six priestesses. Their supervision was the responsibility of a senior vestal, but their selection and governance were overseen by Rome's chief male priest, the Pontifex Maximus, which, during the Imperial era, meant the emperor.

The virgin priestesses of Vesta, who served in her temple and tended to the eternal fire, were closely linked to the earliest Roman traditions. Their presence at Alba Longa is tied to these traditions, as Silvia, the mother of Romulus, was part of their sisterhood. The establishment of the Vestal Virgins in the city, like many aspects of state religion, is typically attributed to Numa Pompilius, a Sabine and Rome's second king. Known as the most religious of Rome's seven kings, it is fitting that Numa was responsible for founding the cult of Vesta and the order of the Vestal Virgins.

Numa selected four, two from the Titienses, two from the Ramnes and two more were later added from the Luceres by Tarquinius Priscus, according to Plutarch or by Servius Tullius according to Dionysius of Halicarnassus. (The first Roman tribes were probably ethnic in origin and consisted of the Titienses (Tities), Ramnenses (Ramnes), and Luceres.) The number of six Vestal Virgins remained unchanged when Plutarch wrote about them, and the claim that this number was later increased to seven is based on very unreliable evidence.

The Vestal Virgins were originally selected (the technical term is "capere") by the king, and later as aforementioned, during the Republic and Empire, by the Pontifex Maximus. The chosen maiden had to be between six and ten years old, physically flawless, with all senses intact, the daughter of freeborn parents who had never been slaves, who engaged in no dishonorable occupation, and whose family resided in Italy.

After being selected, their hair was cut off and hung on an ancient lotus tree standing in the grove of Vesta.

The period of service for a Vestal Virgin lasted thirty years. The first ten years were spent learning their sacred duties, during which they were called discipula (female student). The next ten years were dedicated to performing these duties, and the final ten years were spent instructing new novices. Throughout their service, they were bound by a solemn vow of chastity. After completing the thirty years, they could choose to renounce their office, return to secular life, and even marry.

However, few took advantage of this option, and those who did often lived in sorrow and remorse due to their established habits. Consequently, such a decision was considered ominous, and most priestesses remained in the service of the goddess until their death. (Vestales. Article by William Ramsay, M.A., Professor of Humanity in the University of Glasgow.)

“Next, he added to the four holy virgins who had the custody of the perpetual fire two others; for the sacrifices performed on behalf of the state at which these priestesses of Vesta were required to be present being now increased, the four were not thought sufficient. The example of Tarquinius was followed by the rest of the kings and to this day six priestesses of Vesta are appointed. He seems also to have first devised the punishments which are inflicted by the pontiffs on those Vestals who do not preserve their chastity, being moved to do so either by his own judgment or, as some believe, in obedience to a dream; and these punishments, according to the interpreters of religious rites, were found after his death among the Sibylline oracles. For in his reign a priestess named Pinaria, the daughter of Publius, was discovered to be approaching the sacrifices in a state of unchastity. The manner of punishing the Vestals who have been debauched has been described by me in the preceding Book.”

The Roman Antiquities of Dionysius of Halicarnassus

What was the everyday life of the Vestal Virgins?

For the emperor and other prominent male patricians, the Vestals safeguarded important documents such as wills. The Chief Vestal at the time of Augustus' death informed Livia of his will's contents. The Vestal Virgins also enjoyed two other legal privileges typically reserved for elite Roman men: the right to be preceded by a lictor in public and the right to ride through the streets of Rome in a special carriage called a carpentum.

Their primary duty was to take turns watching the eternal fire on the altar of Vesta, as its extinction was considered the most ominous of prodigies, symbolizing the potential downfall of the state. If the fire went out due to a priestess's negligence, she was stripped and scourged by the Pontifex Maximus in darkness and behind a screen, who would then rekindle the flame by rubbing two pieces of wood from a felix arbor together.

The Vestals' other duties included presenting offerings to the goddess at designated times, and each morning sprinkling and purifying the shrine with water. Initially, this water was to be drawn from the Egerian fountain according to Numa's institution, but later it was acceptable to use any water from a living spring or running stream, provided it had not passed through pipes. For sacrificial purposes, the water was mixed with muries, salt pounded in a mortar, placed in an earthen jar, and baked in an oven.

The Vestals also participated in all major public religious rites, such as the festivals of Bona Dea and temple consecrations, attended priestly banquets, and were present at significant events like Cicero's solemn appeal to the gods during Catiline's conspiracy. They also safeguarded the sacred relics known as the fatale pignus imperii, the fate-granted pledge for the permanence of Roman rule, kept in the innermost sanctuary (penus Vestae), which only the Vestals and the chief pontifex could enter.

The exact nature of this object was unknown, with some believing it to be the Palladium, others the Samothracian gods brought by Dardanus to Troy and later to Italy by Aeneas. It was believed to be contained in a small, tightly sealed earthen jar, with an identical but empty jar beside it.

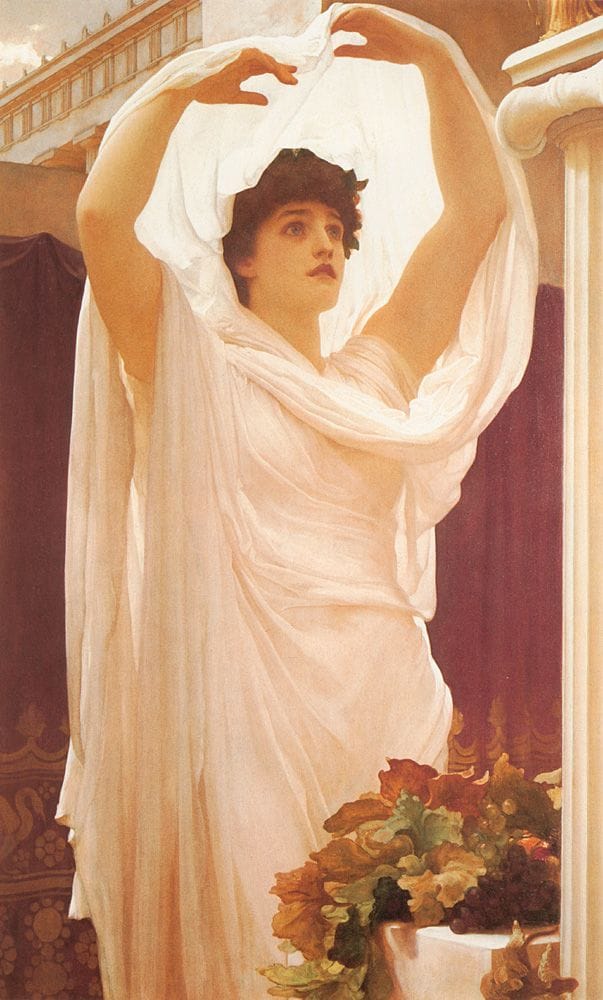

Similar to the attire of a respectable matrona, the costume of a Vestal visibly demonstrated her social status and moral integrity. The complete Vestal regalia included the seni crines (a six-tressed hairstyle), a headdress made of the infula and vittae (woolen bands), a veil called the suffibulum, a palla (mantle), the soft shoes typical of a priestess, and a long tunica (tunic).

Unlike other Roman women, Vestals enjoyed several privileges: they could own property, were exempt from certain taxes, and were freed from their family's patriarchal authority (patria potestas). They had the ability to make their own wills and could give evidence in court without needing to swear an oath.

These rights came at a high cost: 30 years of enforced chastity. Many historians believe that the state's health was linked to the virtue of its women. Since the Vestals' purity was highly visible and sacred, breaking their vow of chastity was met with severe penalties. As it was forbidden to shed a Vestal Virgin's blood, they were executed by immuration—being bricked up in a chamber and left to starve. Her sexual partner faced an equally brutal punishment: death by whipping. Throughout Roman history, there are numerous instances of these harsh sentences being carried out. (National Geographic. Rome's Vestal Virgins: protectors of the city's sacred flame)

Their escort ensured their protection, and if they encountered a convicted criminal, he would escape punishment. It was believed that wills, contracts, and treasures were safest in their sanctuary. They held a place of honor in the theater and at fencing matches, and they were particularly fond of watching gladiator fights. During these matches, they would signal the mortal blow or, more rarely, a pardon by gestures of their thumbs.

Upon their death, Vestals were allowed to be buried within the city walls, a privilege prohibited by the law of the Twelve Tables for others. To support themselves, they received a scholarship from the public treasury, likely in kind, and they probably also owned property, like other priests.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: