Trajan’s Bridge: World’s First to Surpass 1km, 2,000+ Years Ago

Trajan's Bridge, also called Bridge of Apollodorus over the Danube, was a Roman segmental arch bridge, the first bridge to be built over the lower Danube and considered one of the greatest achievements in Roman architecture.

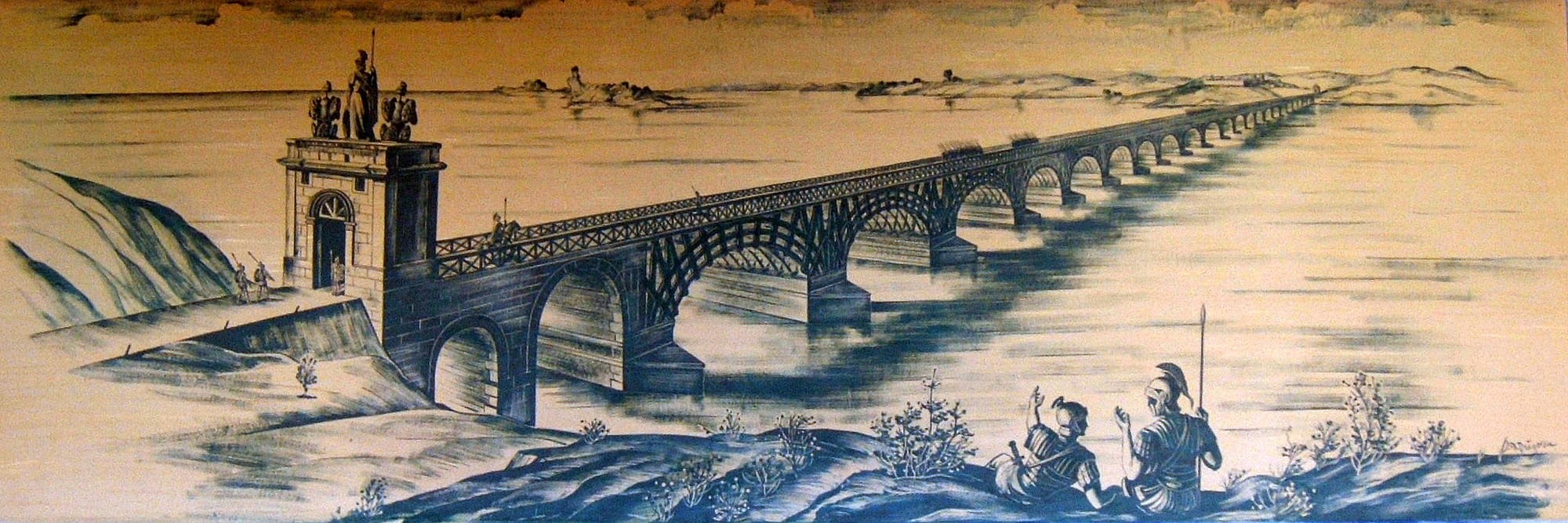

Trajan's bridge was one of the architectural wonders of Europe at the time of its construction. Among Roman architectural works, Trajan’s bridge is one of the few whose appearance we can assess with reasonable accuracy.

Based on written records, surviving remnants, and especially the famous depiction on Trajan's Column, we know that the bridge's support structures, both on the riverbank and in the riverbed, were made of masonry. The bridge’s wooden latticed framework rested atop these masonry pillars in the riverbed, with many details clearly represented on the column in Rome.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the bridge is the method of its construction during Roman times. With twenty pillars set in the Danube riverbed using caissons and spanning 55 meters between each pillar, its construction was a remarkable architectural feat. The bridge's design remains significant in contemporary studies of Roman bridge-building techniques and wooden scaffolding.

A Bridge Designed and Built to Amaze Next Generations

A famous architectural achievement of the Roman Empire, Trajan’s Bridge, is a 3,600-foot-long (1.1 km), twenty-span wooden structure built on stone piers. Constructed between 103 and 105 AD by Emperor Trajan and his chief engineer Apollodorus, the bridge crossed the Danube River.

During this time, the Roman Empire covered much of present-day Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. To consolidate and expand his vast empire, Trajan developed permanent roads and bridges to facilitate the movement of troops and trade. Although the Romans are famous for their stone buildings and bridges, many, like Caesar’s and Trajan’s bridges, were constructed using wood.

The Consruction of the Bridge

The construction of the bridge —initiated by Emperor Trajan and designed by the architect Apollodorus, as aforementioned– took place between 103 and 105 AD. Spanning the Danube River, it served as a key connection between the newly-established province of Dacia and the rest of the Roman Empire, and it became known as Trajan’s Bridge.

The bridge's main structure consisted of 28 support pillars, though only eight have been explored through archaeological investigations—four on the Romanian side and four on the Serbian side. All pillars, except for the one closest to the riverbank, are preserved at the foundation level, with partial remains of walls above that zone. The fourth bank-side masonry pillar, which includes a platform for the wooden structure, is preserved more than 8 meters above the foundation zone and is the best-preserved section of the bridge on the Serbian side.

The pillars in the riverbed, which supported the wooden arches and the platform above, are no longer visible above the water's surface and are in poor condition. They have been examined using hydrographic and geophysical sonar techniques, and later modeled and analyzed with photogrammetric methods. (Trajan’s Bridge – Analysis of Apolodorus’ Design Concept, by Igor Bjeli, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade, Serbia)

How do we know what we know, about Trajan’s Bridge?

Trajan’s bridge, stands out as the most remarkable of Trajan's military bridges, surpassing others over the Rhine, the Tagus, and elsewhere. The historian Cassius Dio provides a brief account of the bridge in his Roman History, noting its twenty stone piers, each 150 feet (±45 meters) high, 60 feet (±18 meters) wide, and spaced 170 feet (±52 meters) apart, connected by arches.

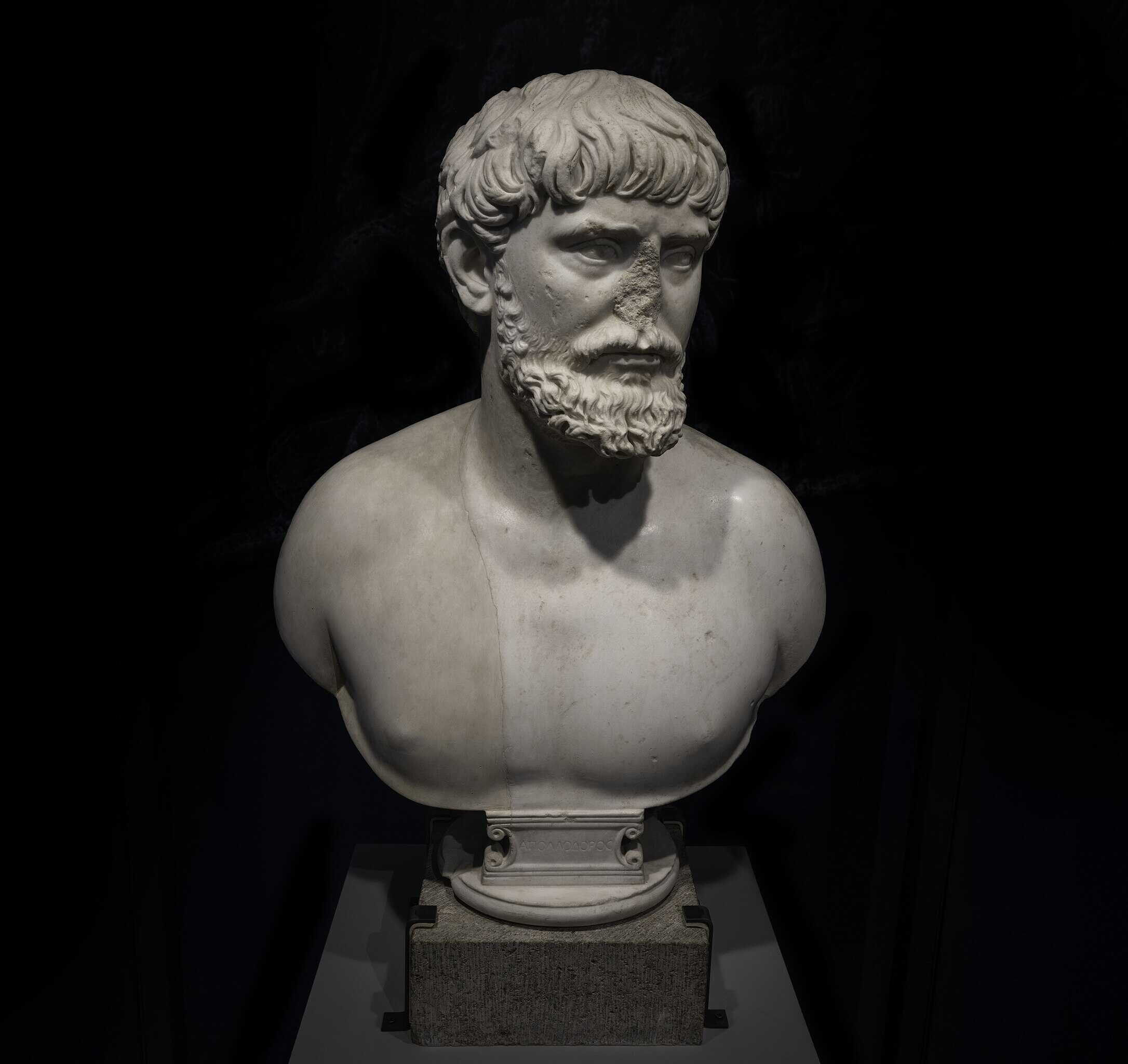

Although in Dio’s time the piers were all that remained, he remarked that their grandeur demonstrated the power of human ingenuity. Both Dio and Procopius confirmed that Apollodorus designed the bridge, and Procopius added that, by the 6th century, the ruins obstructed the Danube’s flow. Apollodorus also designed Trajan's Forum in Rome, and his death at the hands of Hadrian was recorded by Dio and others.

Later historians like Aurelius Victor and Tzetzes provided more details, with Tzetzes mentioning that Apollodorus even constructed an island in the Danube. If Apollodorus' account of his work had survived, it might clarify some of Dio's exaggerations, such as his description of the Danube’s "violent and deep" current. In reality, the river near the bridge is relatively wide, shallow, and gentle, though conditions may have changed since Dio’s time. The reported height of 145.5 feet also seems excessive, as the low banks of the river would not require such an elevation.

The Bridge’s Standing Remains

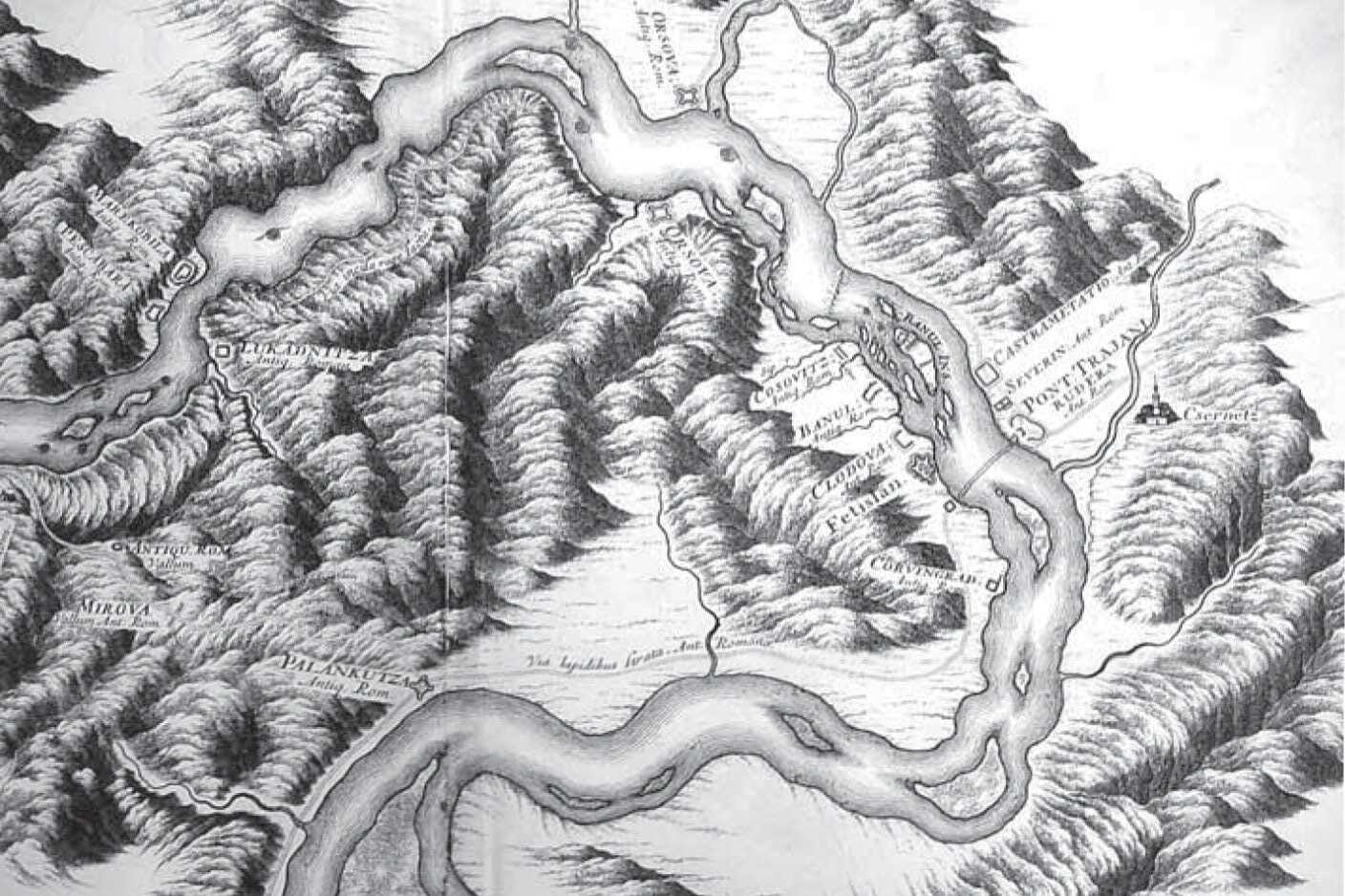

Nevertheless, Trajan’s bridge remains a unique architectural feat, unmatched in the region even in modern times. Its remnants can still be seen at low water near Turnu Severinu, Romania, the site of the Roman outpost Drobetae. Built to span the river to Egeta on the opposite bank, where Roman legions were once stationed, the bridge’s remains today include fragments of masonry on both sides of the river and remnants of the foundation piers visible in the water.

An island near the middle of the river may represent the artificial island created by Apollodorus. Nineteen substructures of the bridge, excluding the end buttresses, have been identified, and even fragments of the wooden superstructure were discovered in 1858 by Austrian engineers.

Trajan’s Bridge North Bank, in Romania

Trajan’s Bridge South Bank, in Serbia

While Dio’s measurements were somewhat inaccurate, the actual piers averaged 170 feet apart and were around 45-47 feet long and 69-72 feet wide. These massive piers, made from opus incertum and encased in stone, were designed to support the arched roadway and withstand the river’s forces.

The Artistic Representations of Trajan’s Bridge

In addition to the sparse physical remains, there are several artistic depictions of Trajan’s bridge found in Roman works of art. These show that the arches and roadway were constructed from wood, as one would expect for spans of such length.

The bridge is partially depicted in one of the relief scenes on the Column of Trajan in Rome. In this scene, a sacrifice is being made, likely to celebrate the completion of the bridge. In the foreground, Emperor Trajan stands with several others, including Hadrian, who was one of Trajan's generals at the time, and Apollodorus, the architect, around an altar where a priest is about to sacrifice an ox.

In the background, five square pillars and five arches of the bridge can be seen, along with the wooden roadway and its long balustrade. The roadway is accessed from the Moesian side by a staircase that leads through a monumental gateway, and fortresses are shown at both ends of the bridge.

Another scene on the column, showing the Roman army marching down a short, inclined bridge, has been interpreted by Cichorius as the Dacian side of the Danube bridge, where it slopes down toward the riverbank.

Based on Procopius' statement that Apollodorus constructed an island in the riverbed, and a letter from Pliny the Younger that mentions rivers being redirected into new channels, Cichorius theorizes that a canal was built at the Dacian end of the bridge to divert some of the river’s flow, reducing the strength of the current.

He believes this canal is depicted in the second scene and uses it to support his reconstruction of the bridge. However, no evidence of such a canal exists today, and most researchers believe Pliny’s statement refers to Trajan’s redirection of the Sargetia River to uncover Decebalus' hidden treasure in its bed.

On the reverse side of a large bronze medallion in the Cabinet des Medailles in Paris, one large arch of Trajan's bridge is depicted, and several of Trajan's coins show fifteen arches along with statue-crowned towers at both ends. The bridge was likely built between the First and Second Dacian Wars and was completed by 105 A.D., in time for troops to cross the river at the start of the second conflict.

Dio records that Trajan constructed the bridge for easier access into Dacia in case of future conflicts but notes that Hadrian later removed the surface structure due to concerns that barbarians could overpower the guards and cross into Moesia. Hadrian is known to have considered abandoning Dacia, only refraining out of concern for the Roman settlers in the region. It seems contradictory, however, that he would keep the province but cut off its only secure connection.

This leads us to consider another motive beyond Dio's explanation for the bridge's destruction. Hadrian’s actions may have been influenced by personal factors. Dio recounts an incident where Hadrian offered suggestions on the bridge's design, only to be dismissed by the architect, Apollodorus. This insult, along with jealousy of Apollodorus' talents, might have driven Hadrian to not only destroy the architect but also the bridge itself.

Two centuries later, in 328 A.D., Constantine restored the arches and roadway during a campaign against the Goths, as mentioned in the Chronicon Paschale (a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. However, subsequent invasions by the Goths and Huns ultimately led to the bridge being permanently dismantled. (Trajan's Danube Road and Bridge, by Walter Woodburn Hyde)

Going Down in History

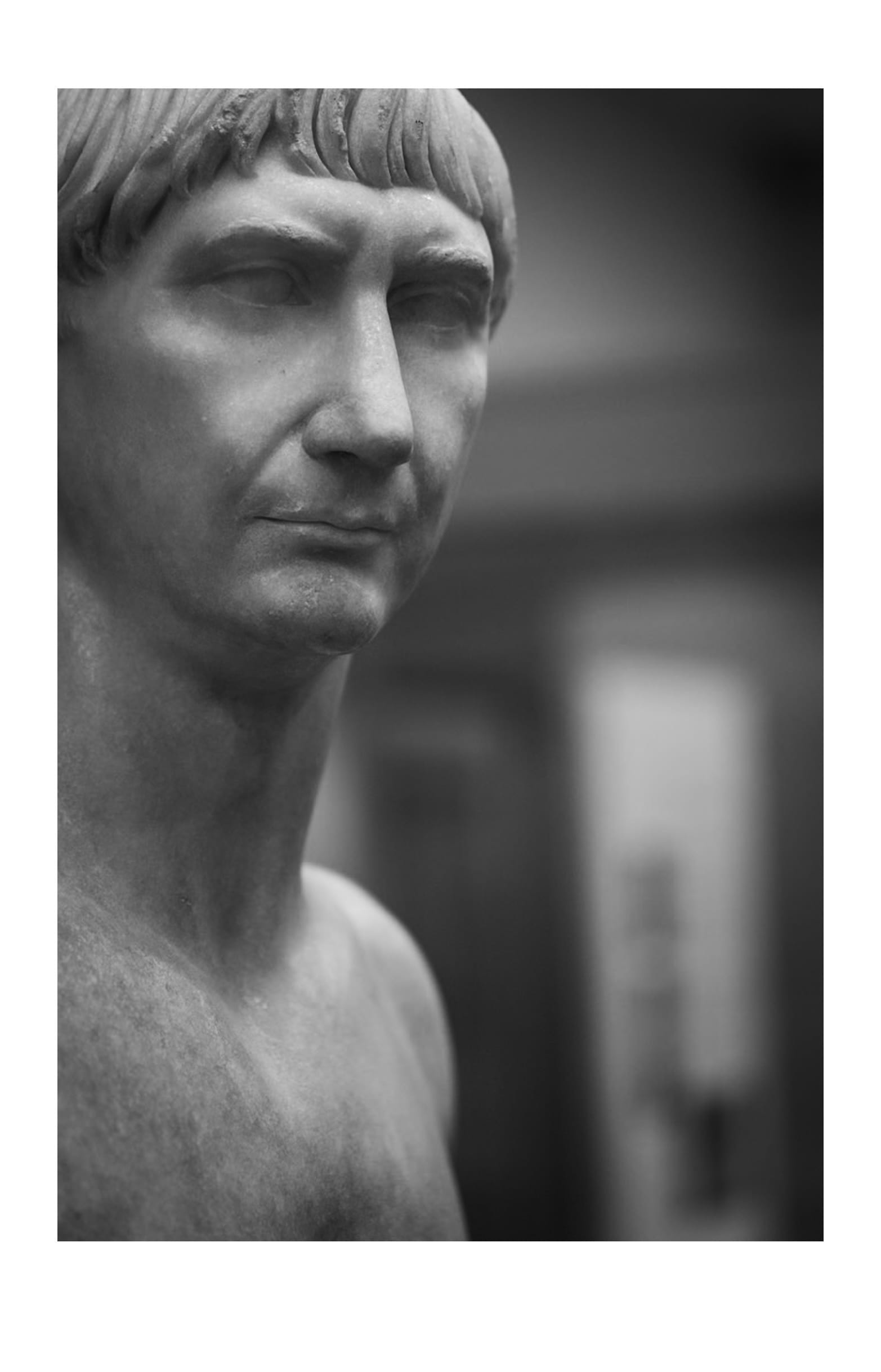

With the Danube project, Trajan had placed himself in a long line of distinguished bridge-builders, such as Darius of Persia, who bridged the Bosphorus; Darius's son Xerxes, who built a bridge of boats across the Hellespont; Seleucus I Nicator, who connected Apamea and Zeugma (meaning "Bridgetown") on the Euphrates; Julius Caesar, who constructed a bridge across the Rhine in just ten days; and Caligula, whose bridge of boats between Baiae and Puteoli was meant to outshine the achievements of Darius and Xerxes, providing a platform for his triumphal march across the sea.

The impact of Trajan's engineering skill on his contemporaries is confirmed by the Younger Pliny.

Trajan’s bust. Credits: Ramon Stoppelenburg, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

To Pliny, the Romans' ability to "divert the course of rivers and throw great bridges across them" was the most remarkable accomplishment of the Dacian campaigns. In a letter to Caninius Rufus in 107, Pliny praises his friend's idea to write an epic poem about the Dacian Wars, noting that the subject provides the chance to "sing of rivers turned into new channels, and rivers bridged for the first time, of camps pitched upon craggy mountains."

For Pliny, the true legend of the Dacian Wars lies not in the battlefield victories or the heroic suicide of Decebalus, but in Rome’s triumph over nature. (The Trophy on the Bridge and the Roman Triumph over Nature, by Fred S. Kleiner)

"I greatly approve your design of writing a poem upon the Dacian war, for where could you have chosen a subject so new, so full of events, so extensive, and so poetical?

A subject which while it has all the marvellous of fiction, has all the solidity of truth.

You will sing of rivers turned into new channels, and rivers bridged for the first time, of camps pitched upon craggy mountains, and of a king superior to adversity, though forced to abandon his capital city and even his life.

You will describe, too, the victor's double triumph, one of which was the first that was ever gained over that nation, till then unsubdued, as the other was the final."

Trajan’s Bridge, the longest in the world at the time, remained an architectural phenomenon for centuries, built over a fast-flowing river and in the proximity of enemy territory. The most well known description of this bridge, was done by Cassius Dio, in his Roman History:

“Trajan constructed over the Ister [Danube] a stone bridge for which I cannot sufficiently admire him. Brilliant, indeed, as are his other achievements, yet this surpasses them.

For it has twenty piers of squared stone one hundred and fifty feet in height above the foundations and sixty in width, and these, standing at a distance of one hundred and seventy feet from one another, are connected by arches.

How, then, could one fail to be astonished at the expenditure made upon them, or at the way in which each of them was placed in a river so deep, in water so full of eddies, and on a bottom so muddy? For it was impossible, of course, to divert the stream anywhere.

I have spoken of the width of the river; but the stream is not uniformly so narrow, since it covers in some places twice, and in others thrice as much ground, but the narrowest point and the one in that region best suited to building a bridge has the width named.

Yet the very fact that river in its descent is here contracted from a great flood to such a narrow channel, after which it again expands into a greater flood, makes it all the more violent and deep, and this feature must be considered in estimating the difficulty of constructing the bridge.

This, too, then, is one of the achievements that show the magnitude of Trajan's designs, though the bridge is of no use to us; for merely the piers are standing, affording no means of crossing, as if they had been erected for the sole purpose of demonstrating that there is nothing which human ingenuity cannot accomplish.

Trajan built the bridge because he feared that some time when the Ister was frozen over war might be made upon the Romans on the further side, and he wished to facilitate access to them by this means.”

The Strategic Location of Trajan’s Bridge

The Roman road network was vast across the empire, but Trajan sought improved access from Viminacium, his westernmost point, for his military campaigns into Dacia. The road crossed the Danube at Trajan’s Bridge, located below the Iron Gates near modern-day Orsova.

At this location, the Danube flows through the Carpathian Mountains, specifically the Kazan Defile, a narrow, steep gorge with cliffs reaching 2,000 feet (610 meters) and a width as narrow as 350 feet (107 meters), with rapids stretching for about 1.5 miles (2.4 km). The river reached depths of up to 180 feet (55 meters) in some areas and widened to over 3,000 feet (914 meters) at the bridge site.

One of Trajan’s significant infrastructure projects was the construction of a road along the western face of the defile. In certain sections, the road was built on cantilevered wooden structures anchored into the rock. This road is now submerged due to the construction of a downstream dam. The modern city of Drobeta-Turnu Severin occupies the northern (eastern) end of the original bridge.

The Bridge’s Deterioration

Procopius of Caesarea was the next ancient author to provide an account of the bridge site. Writing around 550 AD in his work Buildings (De Aedificiis), which mainly focused on the construction projects of Emperor Justinian, Procopius also mentioned the remnants of Trajan’s Bridge.

According to Procopius, by the mid-sixth century, Trajan’s Bridge had fallen into ruins, obstructing river navigation. To restore navigability, a canal was reportedly dug around the northern (Romanian) end of the bridge. However, this task likely proved difficult, as much of the bridge and its piers had already been eroded by the river.

Scholars speculated that this canal may have been part of the Danube when Trajan originally built the bridge. If so, Trajan would have had to construct an additional small, low-level bridge over this branch, in addition to the main structure.

This theory is supported by the name of the fort on the Serbian side, “Pontes,” the plural of pons (Latin for bridge), and a suggestion from Trajan’s Column that a lower-level bridge may have existed on the Serbian side of the river. (Trajan's Bridge: The World's First Long-Span Wooden Bridge, by Francis E. Griggs, Jr.)

Tabula Traiana and Decebalus’ Imposing Statue

The Tabula Traiana is a Roman memorial plaque located in Serbia, commemorating Emperor Trajan's construction of the military road along the Danube River during his campaigns against Dacia. The plaque, originally inscribed into the rockface along the Danube’s Iron Gates, marks the final victory over the Dacians in 105 AD and celebrates the completion of the infrastructure that enabled Roman forces to conquer Dacia.

The tabula itself was relocated in the late 1960s when the construction of the Iron Gates Dam threatened to submerge the original site. To preserve it, engineers moved the entire 300-ton rock slab on which the plaque is carved about 50 meters higher on the cliffside, where it remains visible only from the river.

On the opposite bank of the Danube, in Romania, stands a colossal rock sculpture of the Dacian king Decebalus, Trajan’s formidable opponent during the Dacian Wars. This statue, created between 1994 and 2004, is the largest rock sculpture in Europe, standing at 55 meters high and 25 meters wide. Commissioned by Romanian businessman Iosif Constantin Drăgan, the statue symbolizes Decebalus as a national hero, gazing across the river towards the Tabula Traiana, symbolizing the confrontation between the Dacians and Romans.

The move to relocate the Tabula Traiana was a crucial preservation effort. It not only saved the historical artifact from being lost to rising waters but also maintained the symbolic dialogue between the Roman inscription and the statue of Decebalus. The positioning of Decebalus's statue is significant as it faces the inscription of his conqueror, providing a dramatic visual representation of the ancient conflict that shaped the region’s history. Drăgan, a proponent of Romanian nationalism, intentionally placed the statue in a way that immortalizes Decebalus as a central figure of Romanian heritage.

The Tabula Traiana inscription, originally meant to celebrate Roman engineering and military success, now serves a dual function in modern times: while it stands as a Roman relic, it also complements the monument of Decebalus, creating a narrative of resistance and eventual conquest. This juxtaposition speaks volumes about how historical symbols are reused in nationalistic narratives, especially when considering that Decebalus’s statue was crafted during a period of resurgent Romanian pride in Dacian heritage.

The inscription reads:

IMP. CAESAR. DIVI. NERVAE. F

NERVA TRAIANVS. AVG. GERM

PONTIF MAXIMUS TRIB POT IIII

PATER PATRIAE COS III

MONTIBVS EXCISI(s) ANCO(ni)BVS

SVBLAT(i)S VIA(m) F(ecit)

The text was interpreted by Otto Benndorf to mean:

Emperor Caesar son of the divine Nerva, Nerva Trajan, the Augustus, Germanicus, Pontifex Maximus, invested for the fourth time as Tribune, Father of the Fatherland, Consul for the third time, excavating mountain rocks and using wood beams has made this road.

The creation of Decebalus’s sculpture was a monumental task. The project took ten years to complete, with twelve sculptors dynamiting and carving the rock. Underneath the sculpture is a Latin inscription, "DECEBALUS REX—DRAGAN FECIT," which translates to "King Decebalus—Made by Drăgan," marking the strong connection between the businessman’s personal legacy and his vision of Dacian heritage.

Both the Tabula Traiana and the statue of Decebalus stand as reminders of the historical and ideological conflicts that shaped the region. Their proximity across the Danube serves as a symbol of the enduring legacy of the Roman Empire and the Dacian resistance, which continues to resonate in the cultural memory of Romania and Serbia today.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: