To Adopt or Not to Adopt? Rome Took a Clear Position

Some Roman decisions were made quietly, but their effects were permanent: names changed, heirs appeared, and obligations shifted hands. Behind the formal language of law stood a society trying to protect continuity in a world marked by mortality, status, and competing claims.

In Roman society, family was not only a matter of affection or descent. It was a legal structure tied to property, memory, religious duty, and public standing. When that structure was threatened – by the absence of an heir, the extinction of a name, or the risk of a household ending – Romans did not leave the outcome to chance. They turned instead to a formal solution, one that could redefine identity, rewrite lineage, and secure continuity across generations.

A Different Starting Point

In the modern Western world, adoption is usually understood as a response to the needs of children. It is commonly framed as a way for adults who wish to raise children to provide care for those who cannot remain with their birth families. Over time, changing attitudes toward single parenthood and family support have reduced the number of children available for adoption, while international adoption has raised complex questions about inequality, displacement, and power.

Rome operated within a very different set of conditions. Family life unfolded in a high-mortality environment, where childhood illness, maternal death, and the early loss of parents were common. Even among the elite, not all children survived to adulthood. Large families did not guarantee continuity, and the survival of heirs could not be assumed.

Roman households were also shaped by sharp social hierarchies and the widespread presence of enslaved labour. Child-rearing was often delegated to wet nurses and household staff, which could distance parents from early upbringing. At the same time, exposure and abandonment were accepted practices, indicating that not all children were regarded as equally worth raising. Decisions about whether a child would be reared at all could be influenced by legitimacy, health, or family circumstance.

These realities placed continuity under constant pressure, particularly among the elite. Childlessness, repeated loss, and fragile family lines were persistent problems. In this context, adoption did not function as a substitute for parenthood in an emotional sense. It functioned as a legal and social mechanism for survival: a way to secure heirs, preserve names, and maintain households when birth alone failed to do so.

Roman family life was also marked by unequal power within the household. Male authority over family structure was extensive, while female perspectives are largely absent from the surviving record. Long periods of male absence due to military or administrative service further shaped family dynamics. Adoption appears most frequently in situations where a man had outlived one or more partners and faced the prospect of his household ending without succession.

Seen against this background, Roman adoption was not an act of rescue or sentiment. It was a calculated response to demographic risk, mortality, and the need for continuity in a society where family survival could never be taken for granted.

Was adoption common in Rome?

It is difficult to measure how widespread adoption was at Rome with precision. Most estimates are based on personal names, since adoption often left traces in nomenclature. Roman naming practices, however, were flexible, and changes that appear to reflect adoption can sometimes be explained in other ways. For this reason, numerical figures can only be approximate.

What the available evidence does indicate is that adoption occurred with some regularity among elite groups. Studies focusing on office-holders suggest that a measurable minority had entered their families through adoption. The proportions vary by context, but they consistently appear in environments where inheritance, office, and family continuity carried particular weight.

These figures are drawn from groups that are both well documented and especially sensitive to succession. They reflect situations in which the absence of a male heir created practical problems that required resolution. The evidence also shows that adoption was employed in circumstances extending beyond private family need, including cases where political or social considerations were involved.

Continuity, Inheritance, and Legal Solutions

In Roman society, adoption was closely tied to the need for continuity within the family. This involved not only the transmission of property, but also the preservation of family rites and obligations. A household without legitimate descendants faced both material and symbolic disruption. In such cases, adoption offered a means of creating an heir where birth had failed to do so.

A Roman without legitimate children could adopt a son who was still under paternal authority in another household, or bring under his power a man who was legally independent. These mechanisms allowed a family line to continue despite the absence of natural offspring. While the original motivations behind adoption—whether religious or economic—cannot be securely identified, the surviving evidence shows that adoption was used repeatedly and in a structured manner.

In the late Republic and early Empire, inheritance considerations appear prominently in the cases that are best documented, alongside an increase in testamentary arrangements.

During the Classical period, the legal recognition of children born outside marriage was extremely limited. Legitimation, understood as the acquisition of paternal authority over such children, was largely unavailable. In general, natural children could not be adopted. A narrow exception existed for men without other children under their authority, who could incorporate certain illegitimate children through specific legal procedures, provided those children were freeborn or freed and met additional conditions.

Even so, this practice does not appear to have been widespread, and adoption more often involved individuals of equivalent social standing.

Restrictions on legitimate marriage further shaped the pool of potential heirs. Certain groups, including soldiers for much of the imperial period, were barred from contracting legal marriages. As a result, children born from concubinage or similar arrangements were excluded from their father’s family unless special legal measures were later introduced.

From the fourth century onward, new forms of legitimation emerged under imperial legislation. These allowed children born from concubinage to be brought under paternal authority in specific circumstances, usually through the subsequent marriage of their parents or by direct imperial approval. Additional provisions linked legitimation to civic obligations, enabling certain children to inherit as legitimate if they entered municipal office. These measures were subject to restrictions and did not apply in cases where marriage had been prohibited at the time of conception.

Over time, the legal framework governing adoption and legitimation continued to change. Adoption remained a formal legal act, but its central role within Roman law diminished in the post-Classical period. Adjustments allowed for the adoption of women and, eventually, for women themselves to adopt, as adoption no longer automatically entailed the creation of paternal authority. Despite these changes, certain formal requirements, including age thresholds and generational distance between adopter and adoptee, were retained.

Breaking the Father’s Power

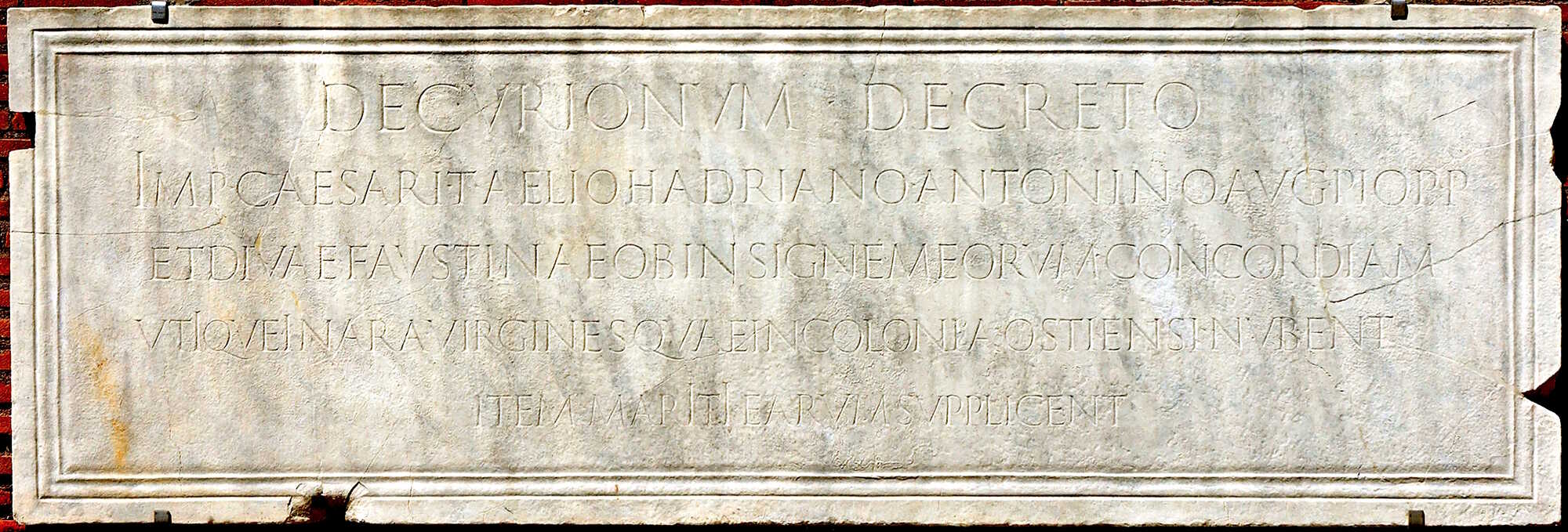

For the earliest phases of Roman history, the structure of the family can only be glimpsed indirectly. No contemporary sources survive, and later authors already stood at a considerable distance from the practices they described. By the late Republic and early Empire, however, one early legal text had acquired particular importance for understanding personal status within the Roman household: a provision of the Twelve Tables concerning the release of a son from paternal authority.

Table IV.2 states:

si pater filium ter venum duit, filius a patre liber esto.

If a father gives his son in sale three times, let the son be free from his father.

This provision defines the conditions under which patria potestas—the father’s legal power over his son—could be broken. Whether the phrase refers to a literal sale or to repeated hiring out for labour has been debated, but its significance lies less in the mechanism than in the principle it establishes. A son could, under specific circumstances, be removed from his father’s authority and placed in a new legal position.

By the second century CE, this procedure was understood as a necessary preliminary to adoption. The jurist Gaius describes the process as a formal sequence of acts designed to dissolve one paternal bond before another could be created:

“Furthermore, parents also stop having under their power children given in adoption. Indeed for a son, supposing he is given in adoption, three mancipations and two intervening manumissions accordingly occur … when a father releases him from power in order to make him legally independent (sui iuris).” (Gaius, Institutes)

The legal writers focus entirely on procedure. They explain how paternal power was transferred, but not why the parties involved sought adoption in any given case.

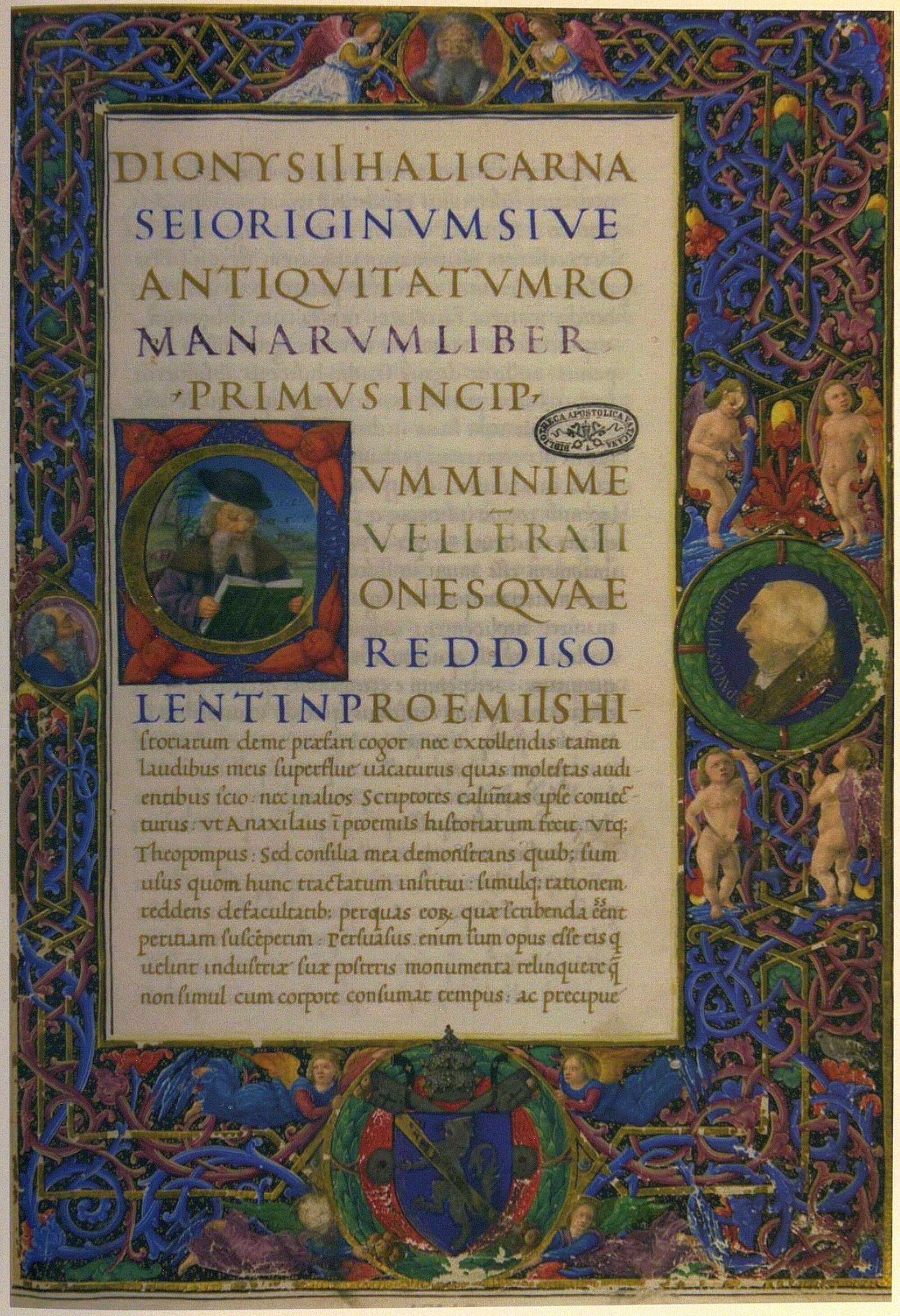

A more interpretative perspective appears in the Augustan period, when Dionysius of Halicarnassus discussed the same rule while reflecting on Rome’s early laws. Treating the provision as a genuine sale of sons, he remarked on the extent of paternal authority in Roman custom:

“He even authorised the father to make money from his son, up to a third sale … giving greater power to the father over his son than to a master over his slaves.” (Roman Antiquities)

Dionysius associated this rule with Rome’s earliest lawgivers and saw it as evidence of Roman severity when compared with Greek practice. He also noted a later restriction attributed to Numa, under which a father who had arranged a lawful marriage for his son would lose the right to sell him. His account reflects an Augustan attempt to reconcile early Roman law with contemporary moral sensibilities.

Whatever its original social context, by the historical period adoption functioned primarily as a legal mechanism affecting inheritance. Once adopted, a son stood in the same legal position as a natural child within his new household. He lost claims in his family of origin and acquired those of a legitimate descendant in the adoptive family.

In financial terms, his position was equally constrained: adoptive and natural sons alike remained subject to the extensive control imposed by patria potestas.

Roman law distinguished between two forms of adoption based on the legal status of the individual concerned. One applied to those already under paternal power; the other to those who were legally independent. Both required formal enactment and public recognition. Emancipation and adoption were thus closely linked from an early stage, and by the time of the Twelve Tables, the legal foundations for both procedures were already in place.

Who Was Allowed to Adopt

Roman adoption was tightly constrained by legal status. Because adoption placed the adoptee under the patria potestas of the adopting father, only a man who already possessed that authority could adopt. A son still under his own father’s power was therefore ineligible.

This restriction shaped practice in noticeable ways. One solution frequently attested in the legal sources was the adoption of a grandson rather than a son. In such cases, a grandfather could establish an heir on behalf of a childless son while remaining within the limits of the law.

This arrangement, however, required careful handling. The consent of the son was necessary before a grandson could be adopted into the family. Without it, the legal position of the child would be ambiguous. Even when consent was given, adoption did not automatically resolve all questions of succession.

A grandson adopted in this way did not inherit directly from the grandfather, since on the grandfather’s death he would fall back under the authority of his natural father. The procedure appears designed to secure continuity across generations rather than to bypass the intermediate heir.

Roman law also imposed age requirements intended to imitate the natural order of parenthood. The adopter was expected to be significantly older than the adoptee, with an eighteen-year gap treated as appropriate. This principle was already recognised in the late Republic and continued to be discussed in later legal writing. Although enforcement could be uneven—particularly in politically sensitive cases—the expectation that adoption should resemble biological succession remained influential.

Further refinements addressed cases that appeared to strain this principle. An older man was not to be adopted by a younger one, and a man was discouraged from adopting multiple individuals without a clear justification. In cases of adrogation, where a legally independent person was taken under paternal authority, additional scrutiny applied.

A man below a certain age was expected to attempt to produce his own heirs unless a specific impediment existed. Exceptions could be made, especially where prior family ties were involved.

These rules reflect an effort to regulate adoption so that it preserved the appearance of natural family order while serving legal and social needs. The legal authorities focused on eligibility, consent, age, and succession, treating adoption not as a private arrangement but as a formal reconfiguration of family structure that required public legitimacy.

Why Women Could Not Normally Adopt

In Roman law, adoption depended on the possession of patria potestas. Because women did not hold this authority, they were in principle excluded from both forms of adoption, adoptio and adrogatio. Adoption was not conceived as a joint decision by a married couple. A woman, unless she was in a manus marriage, did not belong legally to the same familia as her children and exercised no formal authority over them.

Marriage itself was not a requirement for adoption, and many adoptions appear to have taken place in households without a wife, whether through widowhood or lifelong bachelorhood. In this sense, adoption could function as an alternative to marriage rather than an extension of it.

The exclusion of women was reinforced by procedure. Adrogatio was carried out in the comitia curiata, a political assembly in which women could not participate. As a result, female perspectives played no formal role in the selection of adoptees. Adoption had no direct legal implications for a wife, a point underscored by juristic discussions of the adoptee’s position within the household.

Paulus addresses this explicitly when explaining the legal relationships created by adoption:

“A person given in adoption becomes cognate to everyone to whom he becomes agnate… adoption does not create the tie of blood, but the tie of agnation. Hence if I adopt a son, my wife is not in the place of mother to him… but the man whom I adopt does become brother to my daughter… and of course the two are not allowed to marry.”

This passage clarifies that adoption established agnatic, not biological, relationships. The adoptee entered the adopter’s family structure, but not the kinship network of the adopter’s wife.

Some cases from the Republic and early Empire suggest ways in which women could influence succession indirectly. Testamentary arrangements allowed women to require heirs to assume their name, producing effects similar to adoption without formally creating patria potestas. These cases are best understood as testamentary solutions rather than true adoptions.

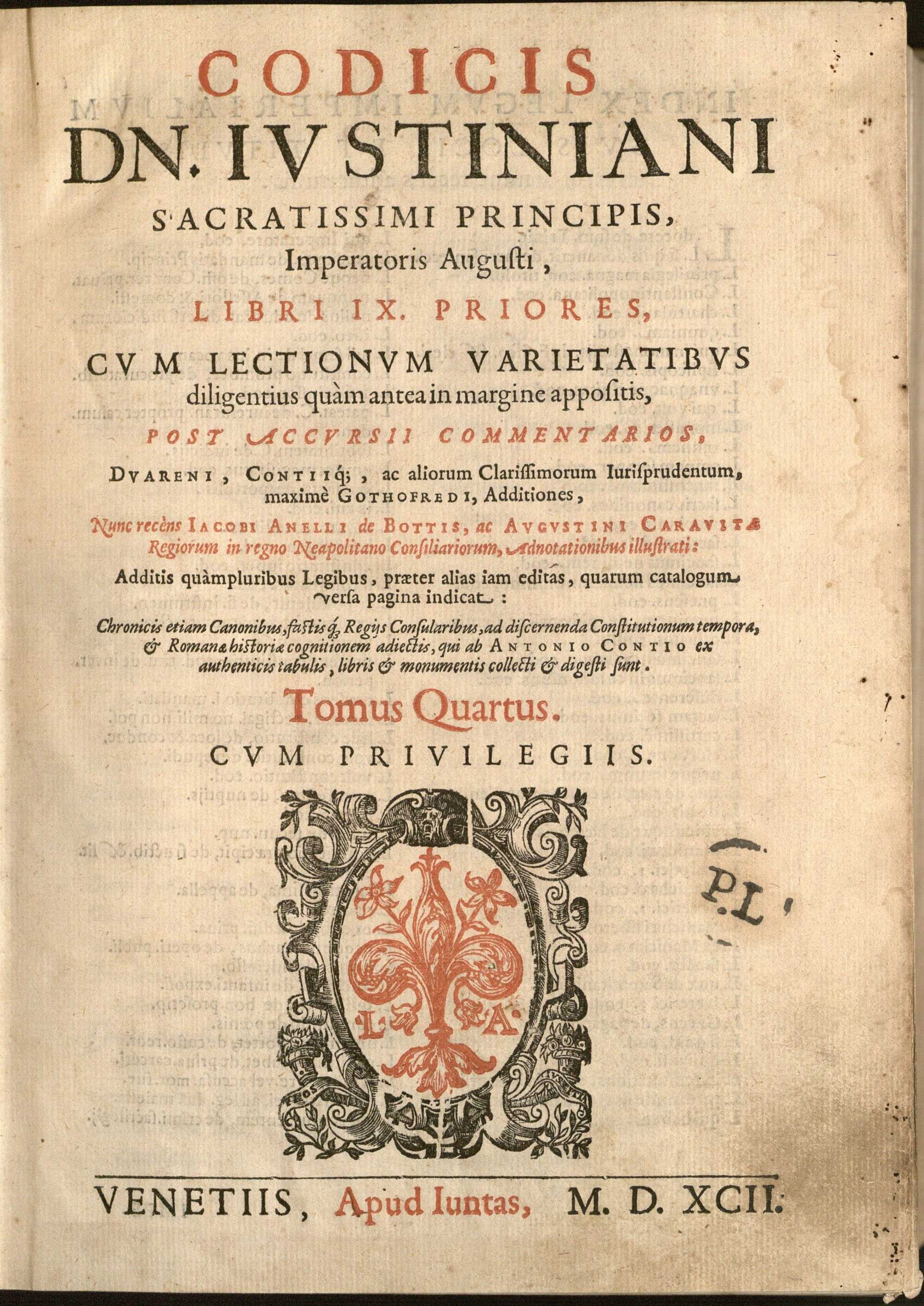

Imperial legislation introduced limited exceptions. A constitution of Diocletian from 291 CE records a highly specific exemption granted to a woman seeking to incorporate her stepson after the loss of her own children:

“It is certain that a woman, who does not even have her own sons in her power, cannot adrogate… we permit you to have him, just as if he were born from you, as a token of a natural and legitimate son.”

This case was treated as exceptional rather than normative. Later juristic opinion confirms that female adoption required direct imperial authorisation:

“Since a woman cannot adopt a son without an order from the emperor…”

The general prohibition remained in force until the time of Justinian, who reiterated the ban while allowing petitions based on exceptional circumstances, including the loss of children. Evidence from late Roman Egypt suggests that private arrangements sometimes bypassed formal law, reflecting a practical recognition of maternal authority, particularly among widows. Testamentary adoption remained the most viable route for women to shape succession, though it did not produce the same legal effects as adoption during life.

Two Ways to Create a Son

Roman law recognised two distinct forms of adoption, depending on whether the act took place in a public or private setting. Our knowledge of these procedures comes largely from imperial-era legal and antiquarian sources, which describe practices already regarded as traditional. Although the evidence is fragmentary, it allows a clear distinction between adoptio and adrogatio, each governed by different legal requirements.

Aulus Gellius offers the most complete surviving explanation of the two procedures:

“When strangers are taken into another family and into the position of children, this occurs either through the praetor or through the people. When it happens through the praetor it is said to be adoptatio, when through the people adrogatio…”

In adoptio, the person being adopted was already under the patria potestas of another father. The procedure required the dissolution of that authority and the formal transfer of power to the adopter, carried out before a magistrate. This was a private act in the sense that it did not involve legislation, though it remained a public legal process. Its structure closely resembled emancipation, except that the final release was omitted, leaving the adoptee under the control of the new paterfamilias.

Adrogatio, by contrast, applied only to individuals who were legally independent (sui iuris) and thus heads of their own households. Because this procedure extinguished one family in order to preserve another, it required public approval. It was carried out before the comitia curiata, under the supervision of the pontiffs, and involved a formal inquiry into the circumstances of the adoption. Gellius records the formula of the popular mandate, which explicitly transferred full paternal authority:

“Will you request and command that Lucius Valerius should be son to Lucius Titius… and that he should have power of life and death over him, as a father has over his son.”

This language reflects the legal comprehensiveness of paternal power rather than its everyday application. The procedure also involved the renunciation of the adoptee’s former family rites, a step that made adrogation both a legal and religious act.

The pontiffs were required to examine several factors before approving an adrogation. These included the adopter’s age and capacity to produce natural heirs, the motives behind the adoption, and the relative status of the parties involved. Cicero’s discussion of the attempted adoption of Clodius illustrates how these criteria could become points of contention, especially when political interests were at stake. Concerns extended not only to the extinction of the adoptee’s family rites but also to the potential harm to his material interests.

Over time, the administration of adrogation changed. While the comitia curiata continued to exist into the imperial period, its role gradually diminished. By the second century CE, adrogation by imperial rescript is attested, with the emperor assuming functions formerly exercised by the pontiffs. The convenience of this procedure appears to have led to the gradual abandonment of popular adrogation at Rome, though the precise point at which this occurred remains uncertain.

Private adoption remained more flexible but was still constrained by legal form. Because the adoptee remained under paternal power, the arrangement was primarily negotiated between senior male members of different households. Financial considerations were central, but short-term political and social interests could also shape decisions. Such motives are difficult to trace, as they rarely surface in surviving legal texts.

Alongside these procedures stood the phenomenon often described as testamentary adoption. Ancient authors use the language of adoption in such cases, but modern analysis suggests that most involved no more than the appointment of an heir combined with the instruction to assume the testator’s name. Only in exceptional circumstances—most notably the case of Octavian – was a formal adrogation carried out after death, and even then under unusual political conditions.

Ancient writers themselves did not consistently distinguish between these different mechanisms. Terms such as adsciscere, in familiam transire, or nomen adsumere could be used to describe a range of arrangements with very different legal effects. This ambiguity reflects a broader Roman tendency to focus less on procedural distinctions than on the visible outcome: the transformation of name, status, and family affiliation.

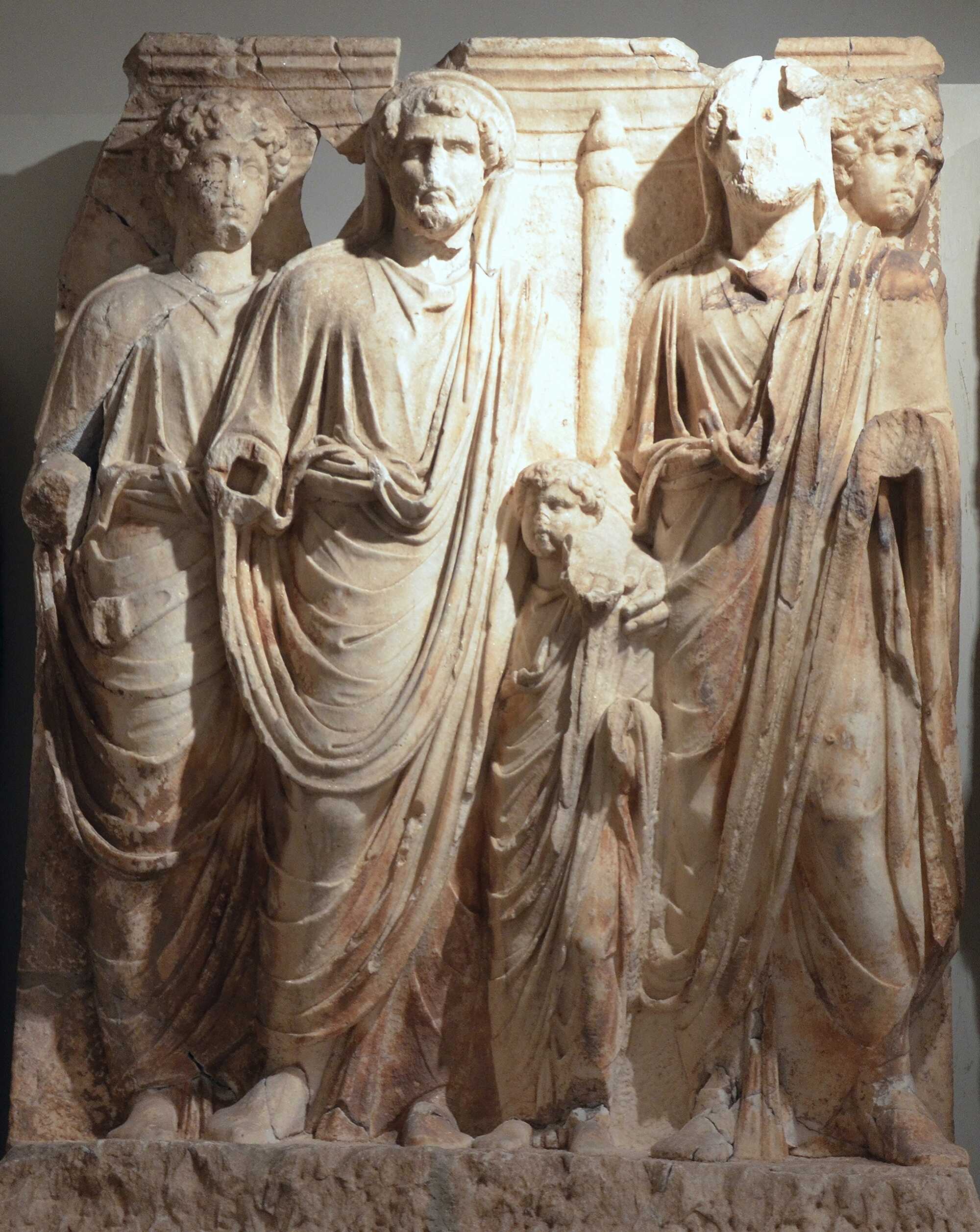

Adoption, Status, and Elite Continuity

Among Rome’s elite, adoption served purposes that remained broadly consistent from the late Republic into the early Empire. Political standing and inheritance lay at the centre of these arrangements. For senators and their families, success was measured through participation in public life, especially advancement along the cursus honorum, military distinction, and the accumulation of honour that accompanied office-holding. Wealth mattered not simply as property, but as a resource that enabled political action and social visibility.

Although Roman elites did not generally treat landed property as an untouchable ancestral possession in the manner of later aristocracies, inheritance still conferred significant power. Control over wealth included the ability to alienate property and to determine succession, and adoption offered a means of directing both. Where natural succession was uncertain or impossible, adoption provided a practical response to demographic vulnerability.

Elite adoption often favoured close relatives or candidates of comparable rank. This increased the likelihood that the adoptee would share the values, ambitions, and expectations of the group. The history of the Scipionic family illustrates how children could be redistributed among branches of a wider kin group to stabilise succession. Such strategies did not always produce the intended outcome. In one prominent case, a father who produced several sons nevertheless saw his surviving heirs absorbed into other families through adoption.

Literary sources rarely describe adoption from the perspective of the adoptee. This may reflect the fact that Roman adoption usually involved individuals of similar status, so the social transition was less dramatic than might be assumed. Where evidence does survive, it suggests that adoption could be integrated into existing family relationships rather than replacing them entirely.

A revealing case appears in the writings of Quintilian. In the preface to Book 6 of the Institutio Oratoria, he mourns the death of his young sons and reflects on the importance of the elder as his hope for old age. Yet this same child had recently been adopted by a consular figure, with a marriage into a praetorian family already envisaged:

“Have I lost you when you have moved closer to expectations of every distinction through your recent adoption by a consular, destined to be son-in-law to a praetorian uncle…?”

The passage shows adoption operating as a mechanism of advancement. The child remained connected to his natal family while gaining a second paternal figure and access to higher social networks. In Quintilian’s case, adoption appears as one of several strategies employed to secure his son’s future, alongside education and arranged marriage. The arrangement also reflects Quintilian’s own concerns about mortality and status, as well as his reliance on extended family networks following the early death of his wife.

Such cases are particularly visible among provincials who rose to prominence under the Empire. For members of this group, adoption could function as a corrective to misfortune or limited origins, a way to realign family prospects with new ambitions. The association between adoption and succession is explicit in contemporary writing, where adoption is described as a means of repairing one’s position in life.

Under the Empire, the broader significance of elite adoption shifted. Senatorial adoptions continued, but their political impact was increasingly shaped by imperial patronage. Attention turned toward the imperial household itself. Early imperial adoptions initially retained the appearance of private family arrangements, but their wider implications were quickly recognised. After the end of the Julio-Claudian line, adoption became an overt instrument of designation, and its political function came to dominate all other considerations. (“Adoption in the Roman world” by Hugh Lindsay)

Roman adoption was less a private choice than a legal instrument that could redirect inheritance, redefine kinship, and keep a household intact. It operated through formal rules, public procedures, and assumptions about authority that shaped who could adopt, who could be adopted, and what changed as a result. In that sense, the Roman answer was not sentimental—it was structural.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: