Tiberius: Power, Paranoia, and Politics in Imperial Rome

Tiberius, Rome’s second emperor, was a ruler shaped by duty, suspicion, and an uneasy relationship with power. Unlike his predecessor Augustus, whose charisma and political acumen forged the foundations of the empire, Tiberius ruled with a more withdrawn and calculating approach

Tiberius’ reign was marked by military success, administrative efficiency, and an increasing paranoia that led to purges and political repression. While historians such as Tacitus and Suetonius paint him as a bitter and reclusive tyrant, others acknowledge his contributions to Rome’s stability. But who was the real Tiberius—an able statesman trapped by circumstance, or a ruler consumed by mistrust and detachment?

The Enigmatic Emperor Who Shaped Rome’s Future

Tiberius' reign, often overshadowed by the grandeur of Augustus and the excesses of later rulers, was nonetheless a defining period in the consolidation of the Roman Empire. A deeply private and reluctant leader, Tiberius navigated the complex political landscape with pragmatism, efficiency, and a deep-seated suspicion that would come to characterize his rule.

Born into the prestigious Claudian family, Tiberius was shaped by a lineage of statesmen, warriors, and reformers who had left their mark on Rome for centuries. Though a Claudian by birth, his ancestry was complicated by adoption and marriage alliances, tying him to the influential Livii Drusi and Julian families.

His early years saw him thrust into the volatile politics of the late Republic, where shifting allegiances and Octavian’s consolidation of power forced his father, Ti. Claudius Nero, into exile. The sudden elevation of his mother, Livia Drusilla, to the role of Augustus’ wife placed Tiberius in the imperial fold, but also under the shadow of the ambitious Julian lineage.

Trained in rhetoric, law, and military strategy, Tiberius was an intellectual with a deep appreciation for history and philosophy. He excelled in military command, securing Rome’s frontiers in Germany, Pannonia, and Armenia, but his personal disposition made him an uneasy participant in the political maneuverings of the imperial court.

His retreat to Rhodes in self-imposed exile remains one of the most puzzling episodes of his life, reflecting both his discomfort with imperial expectations and his growing distrust of Augustus’ succession plans.

Despite his reluctance, Tiberius eventually became Rome’s second emperor in AD 14.

A closeup photo of a bust of roman emperor Tiberius. Credits:

His early rule was marked by administrative competence and military discipline, but his withdrawal from public life and increasing reliance on the ambitious prefect Sejanus led to an era of paranoia and political purges. His final years, spent in isolation on the island of Capri, cemented the image of a suspicious, misanthropic ruler, whose policies—whether wise or oppressive—were dictated by an unshakable belief in the inherent dangers of power.

Yet Tiberius’ reign was crucial in defining the imperial system. He fortified the bureaucratic and military foundations laid by Augustus, resisted reckless expansionism, and upheld a strict financial policy that stabilized Rome’s economy.

While ancient sources, particularly Tacitus and Suetonius, portray him as a tyrant plagued by secrecy and cruelty, modern scholarship offers a more nuanced view of his rule—one of calculated governance, political survival, and a complex personality caught between duty and detachment.

Who, then, was Tiberius?

A capable administrator undone by his mistrust of others? A reluctant ruler trapped in a role he never desired? Or a pragmatic leader whose legacy was distorted by history’s harshest critics?

From Political Refugee to Reluctant Emperor

Tiberius’ life was marked by political maneuvering, shifting allegiances, and the weight of imperial expectations. From the moment he entered the world, his fate was intertwined with Rome’s turbulent political landscape. Born into the prestigious Claudian family but raised in the shadow of the emerging Augustan regime, he was, at different points in his life, both a political refugee and a rising star within the new imperial order.

His early years saw him adopted as heir by M. Gallius, a move that could have signified a shift in allegiance, but Tiberius declined to take the Gallius name, remaining firmly a Nero. The death of his father, Ti. Claudius Nero, in the early 30s BC further cemented his integration into Augustus’ circle, with the future princeps drawing him ever closer. His betrothal to Vipsania, daughter of Augustus’ trusted general Agrippa, further solidified his place in the inner ranks of the new regime.

From an early age, Tiberius was thrust into the world of politics and military affairs. He rode beside Augustus in his Actium triumph, trained alongside his cousin Marcellus, and took part in military campaigns in Spain, earning valuable experience. His role as an advocate in legal cases before the Senate and Augustus himself revealed both his rhetorical skill and his alignment with the imperial court.

When a political crisis arose in 23 BC, Tiberius was called upon to prosecute those who threatened the stability of Augustus’ principate—demonstrating his loyalty but also earning the resentment of Rome’s lingering Republican faction.

A Gold Roman Aureus Coin of Emperor Tiberius. Public domain

His career flourished in the East, where he played a key role in Augustus’ diplomatic efforts with Parthia, securing the return of Crassus’ lost standards and installing a pro-Roman king in Armenia. These missions enhanced his reputation, but they also revealed a key trait: his preference for duty over ambition. Unlike his more charismatic stepbrother, Nero Drusus, Tiberius was methodical, disciplined, and cautious—traits that would come to define his rule.

The evolving Augustan succession plan placed Tiberius in an increasingly complex position. The deaths of Marcellus and Agrippa reshaped the imperial family, and while Agrippa’s sons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, were groomed as heirs, Tiberius remained a key figure. His successful military campaigns in the Alps and Germany further established his credentials, but he remained in the shadow of Augustus’ preferred successors.

By 13 BC, Tiberius had achieved the pinnacle of a traditional senatorial career, serving as consul and leading military operations in Rome’s frontier regions. Yet, his personal life was disrupted when Augustus forced him to divorce Vipsania and marry Julia, the widow of Agrippa and the emperor’s only daughter.

This political marriage, meant to bind him even more closely to the dynasty, was a source of deep personal misery. In the coming years, his growing dissatisfaction and the increasing pressures of the succession crisis would drive him to a self-imposed exile on Rhodes—an episode that underscored his reluctance for supreme power.

Tiberius’ story is one of contradictions. He was a man of immense talent, yet often reluctant to wield power. He was a key architect of Rome’s imperial stability yet haunted by the burdens of rule. His early career—shaped by alliances, military successes, and political survival—set the stage for his eventual reign, which would prove as enigmatic and complex as the man himself. (Tiberius the politician, by Barbara Levick)

Tiberius and Rome’s Northern Frontier: Conquest, Strategy, and Expansion

In 16 BCE, despite having received praetorian rank in 20 BCE, Tiberius formally held the office of praetor at the age of twenty-five. The period following his tenure in this position until his eventual withdrawal to Rhodes was predominantly occupied with military campaigns along Rome’s northern frontier.

Augustus saw considerable work to be done in this region, focusing on three major objectives:

- First, he aimed to subdue the Alpine territories, whose inhabitants frequently raided Italy and Gaul.

- Secondly, he sought to extend Roman control over Illyricum up to the Danube, securing the valleys of the Save and Drave. This expansion would establish a more direct link between Macedonia, Italy, Gaul, and the Rhine. If successful, the Rhine and Danube would serve as Rome’s natural frontiers.

- The third area of military engagement was Germania, where the Romans conducted expeditions across the Rhine, exploring the possibility of extending their control to the Elbe. This initiative was likely driven by the strategic advantage of shorter supply lines that an Elbe–Danube boundary could offer.

To oversee the early phases of this expansion, Augustus traveled to Gaul in 16 BCE, accompanied by Tiberius. The following year, Tiberius and his younger brother, Drusus, launched a campaign against the Rhaetians and Vindelicians. Due to the fragmented nature of ancient sources, their precise movements are difficult to reconstruct.

However, it appears that Drusus initially engaged the Rhaetians near the Tridentine Alps, securing a victory that earned him praetorian honors. Despite this success, the Rhaetians continued to pose a threat to Gaul, though they refrained from further incursions into Italy.

Tiberius later joined forces with Drusus, and together they divided their army, assigning separate detachments to their legates.

Drusus the Elder bust. Credits: Scailyna, CC BY-SA 4.0

Based on the order in which the names of the conquered tribes appear on the victory monument at La Turbie, it is likely that Drusus advanced via the Brenner Pass into Vindelicia, progressing through the Bavarian Alpine foothills into Upper Swabia. Meanwhile, Tiberius appears to have moved eastward from Vindonissa along the Rhine toward Lake Constance, which he crossed by boat. After these initial maneuvers, the brothers coordinated their forces and advanced together.

The rapid movement through the Alpine valleys, coupled with a strategy of dispersing their forces to prevent enemy tribes from massing against them, led to a swift victory. The territory up to the Danube was conquered but not permanently occupied.

At this stage, there were no Roman garrisons positioned directly along the river. Instead, the army was stationed at Oberhausen, allowing for rapid deployment in response to any emerging threats. This approach was likely due to the sparsely populated nature of the Danubian region and the absence of any significant external power capable of mounting an immediate invasion. Consequently, there was little need to station troops in forward positions either to suppress local resistance or to defend against external aggression.

Marriage, Duty, and Succession

By 13 BCE, at the age of twenty-eight, Tiberius had reached the consulship. One of his key responsibilities that year was organizing the celebrations marking Augustus’ return from Gaul. As part of the event, he made a pragmatic decision to seat the young Gaius Caesar beside his adoptive father, Augustus. However, this act earned him a reprimand from the princeps, who likely felt it was too soon for such a public display of Gaius’ position.

That same year, Agrippa returned from the East to assume command in Illyricum. His tribunician power was renewed for another five years, and he departed for the Balkans with imperium superior to that of other provincial governors, ensuring he held supreme authority in the region.

However, his strenuous efforts had taken a toll on his health, and the harsh Pannonian winter proved too much for him. In February of 12 BCE, Agrippa passed away.

Agrippa’s death was a significant loss for Augustus, not only depriving him of his most capable general and administrator but also reigniting the succession dilemma. While Augustus now had heirs in Gaius and Lucius Caesar, he lacked a seasoned and loyal deputy who could protect their interests should he himself die.

The practical solution was clear: Julia, Agrippa’s widow, needed a new husband—someone who could assume Agrippa’s role both politically and within the imperial family. The ideal candidate was Tiberius.

Augustus showed little regard for personal feelings in his dynastic arrangements. It was irrelevant that Tiberius was happily married to Vipsania, that she was pregnant, or that she was still mourning the recent loss of her father. With Agrippa gone, Tiberius had become Rome’s foremost military commander—the only figure capable of succeeding Agrippa as Augustus’ right-hand man.

His prominence and influence were bound to grow, and Augustus could not afford to leave him out of his succession plans. Marrying him to Julia was the logical solution. This union would further intertwine the Julian and Claudian bloodlines, ensure that Gaius and Lucius had a stepfather to guide them, and help contain any ambitions that Tiberius or his mother, Livia, might have nurtured regarding the succession.

Tiberius was ordered to divorce Vipsania, and he complied, becoming betrothed to Julia. However, the marriage did not take place immediately, as Tiberius was dispatched as Augustus’ legate to assume command in Illyricum, filling the vacancy left by Agrippa’s death. It was only in 11 BCE, after two successful campaigns in Pannonia, that the marriage was finally formalized upon his return to Rome.

A flaw in Augustus’ carefully constructed plan soon became evident. In the following year, Julia gave birth to a son in Aquileia. Had the child survived, Tiberius might have been inclined to prioritize his own son over Augustus’ chosen heirs, Gaius and Lucius, potentially disrupting the succession arrangement.

However, the child died in infancy, preventing any such complications. The issue of succession did not arise again, as by 6 BCE—possibly even earlier—Tiberius and Julia had effectively ceased living as husband and wife. (Tiberius, by Robin Seager)

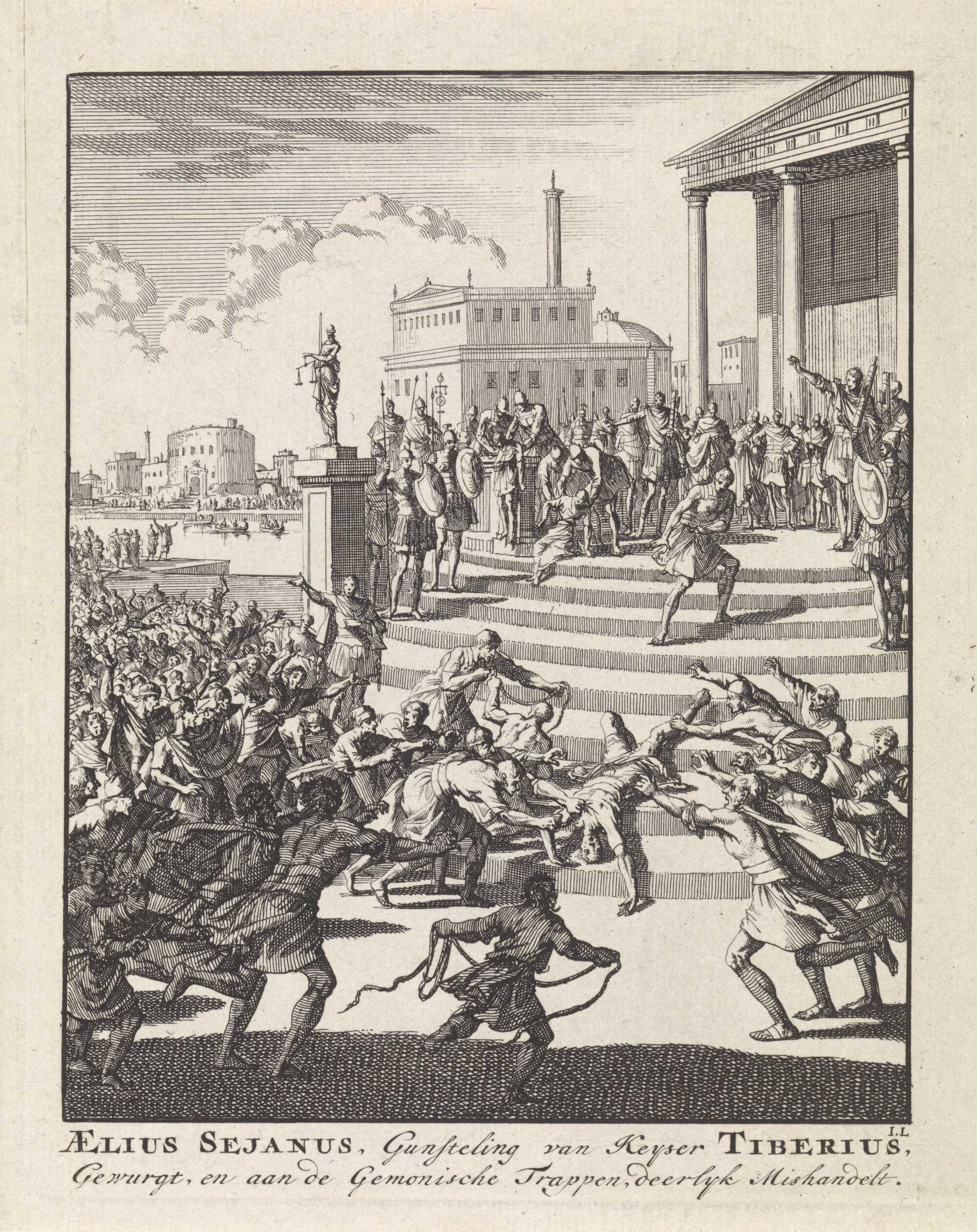

The Fall of Sejanus: A Turning Point in Tiberius’ Reign

Tacitus marks the fall of Sejanus as a defining moment in Tiberius’ life and rule, a shift that plunged Rome into a reign of terror. With Sejanus eliminated, the question of succession appeared to settle, as Gaius Caligula, aided by his chief supporter Macro, solidified his position.

However, the greater consequence of Sejanus’ downfall was the vengeful purge that followed—“a witch-hunt,” as Tacitus suggests—where fear, political opportunism, and betrayal dictated the fate of Rome’s elite. For Tiberius, the discovery that his trusted confidant had been a “murderous schemer” was a profound shock. His paranoia only deepened when Apicata, Sejanus’ former wife, sent him a letter revealing the Prefect’s involvement in the poisoning of his son, Drusus.

Tiberius, already known for his cold and calculated demeanor, did not act in haste. The destruction of Sejanus was a “brilliantly thought out and executed action,” but it did not bring peace. Instead, the emperor retreated further into himself, indulging in self-pity, and addressing the Senate with words laced with irony and despair:

“What I am to write to you, conscript fathers, or how I am to write it, or what I am to refrain from writing at this time, may the gods and goddesses all send me to perdition quicker than I feel I’m going already, if I know.”

The Senate, sensing the shift in power, sought to erase Sejanus from memory. His statues were torn down, and his name was subjected to damnatio memoriae. The senators, eager to prove their loyalty, held an annual festival to commemorate his fall and forbade excessive honors to any future man, except for Macro, the new power behind the throne. Yet, the purges did not stop with Sejanus.

His allies—Blaesus, Bruttedius Niger, and even men of seemingly innocent connection—were swiftly accused and executed. Some, like Sextius Paconianus, were charged with ensnaring Caligula, while others, such as Lucanius Latiaris, were caught in the political web they had once helped weave. The hunt for Sejanus’ supporters extended even to prominent consulars, causing a wave of fear throughout the Senate, as Tacitus notes:

“There was hardly a senator who had no tie with these distinguished men.”

As the purges continued, self-preservation led many to turn against their own allies. Accusations became a weapon—men denounced their friends, and those who had been fervent supporters of Sejanus suddenly became his loudest enemies.

“Men competed to kick the corpse,”

Tacitus remarks, describing how the mob and senators alike rushed to distance themselves from the fallen Prefect. Others, like the former consul L. Fulcinius Trio, attempted to rehabilitate their position by pointing fingers at others, turning the Senate into a theater of suspicion and retribution.

By 33 CE, Tiberius had eradicated the remnants of Sejanus’ network, but his own grip on power had begun to loosen. Isolated on Capri, he seemed more a shadow than a ruler. The year saw the deaths of Agrippina the Elder, the last real opposition to Tiberius, along with her son Drusus, whom the emperor allegedly starved to death.

In a final act of cruelty, Tiberius had Drusus’ dying words recorded and read aloud to the Senate, just as he reminded them that Agrippina had perished on the same date as Sejanus—an unsubtle suggestion that both were equally deserving of their fates. The Senate, in turn, showered him with grotesque flattery, praising his clementia even as bodies continued to pile up.

Though the terror eased somewhat in the last years of Tiberius’ reign, the damage had been done. Rome had become a place where fear ruled, where whispers could mean death, and where the Senate, stripped of dignity, played along with the emperor’s whims.

Meanwhile, Caligula was quietly maneuvering into position, ensuring that, when Tiberius finally died in 37 CE, he would rise unchallenged.

A possible representation of Caligula, smirking from the shadows. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: