The Spiraling Legacy of Trajan's Column: Art, Propaganda, and Power

Trajan's Column is an iconic piece of Roman art and architecture, rich with historical, artistic, and cultural significance.

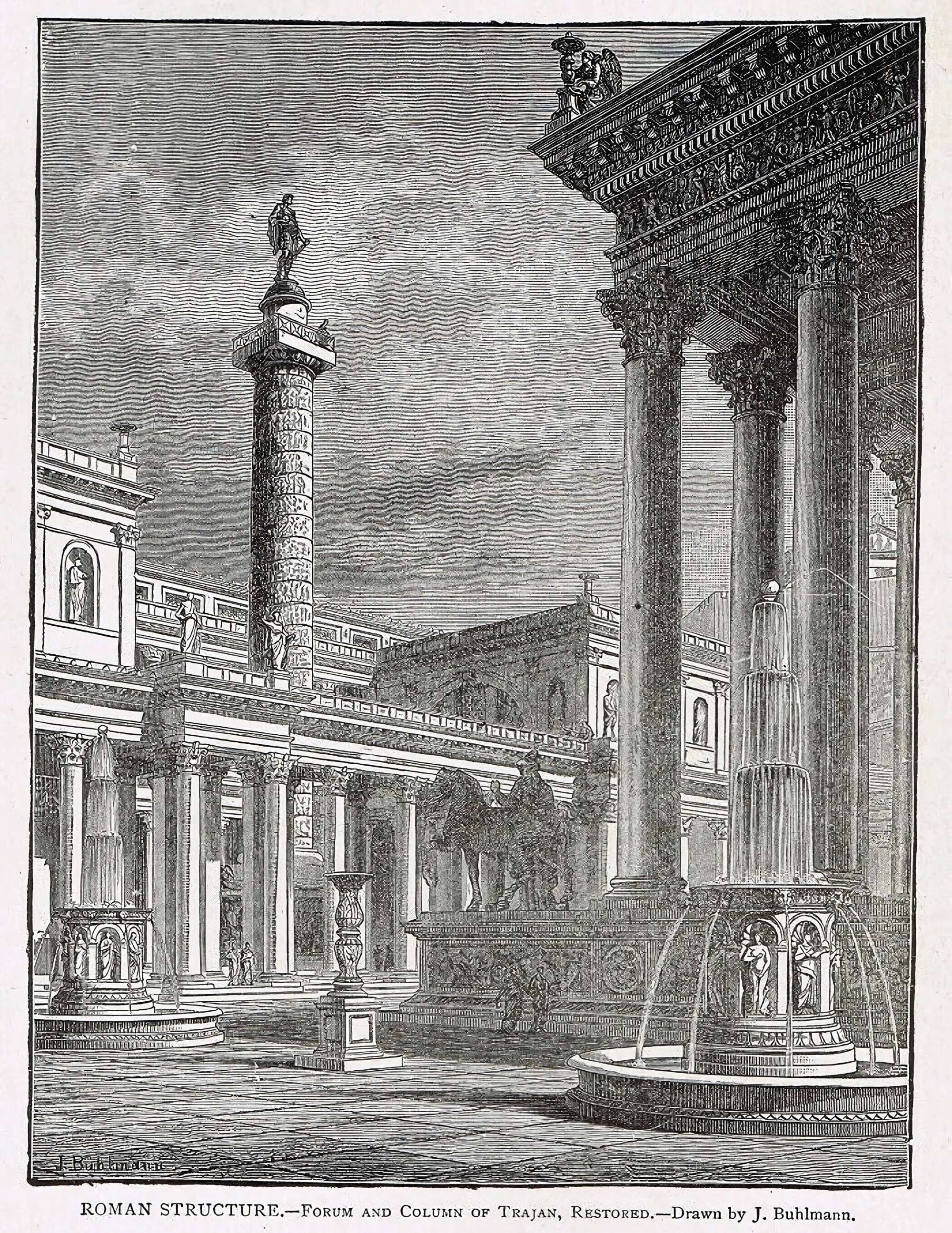

Towering above the Roman Forum, Trajan’s Column stands as an extraordinary proof to the power, ambition, and artistic sophistication of the Roman Empire. Erected in 113 CE to celebrate Emperor Trajan’s victory in the Dacian Wars, this iconic monument is more than just a physical structure; it is a narrative masterpiece that weaves together scenes of battle, diplomacy, and imperial propaganda.

Spiraling upwards for over 30 meters, the column’s intricately carved reliefs tell a story not only of conquest but also of the logistical and administrative prowess that defined Rome’s golden age. A miracle of engineering and storytelling, Trajan’s Column continues to capture the imagination of historians, artists, and visitors, serving as a cultural bridge between antiquity and the modern world.

Its enduring relevance prompts us to ask: how did this remarkable monument come to symbolize both the triumphs and complexities of Rome’s imperial aspirations?

Credits: historyin3D, Instagram

Trajan’s Column: A Monument of Roman Art, History, and Conquest

Located near the grand Ulpian Basilica, the column was surrounded by two libraries—one Greek and one Latin—and possibly encircled by colonnades, as evidenced by the foundations that remain. Adjacent to the column was a temple dedicated to Trajan, likely built later by his successor, Hadrian.

In the center of the forum, a gilded bronze statue of Trajan on horseback commemorated his triumphs, while the surrounding balustrades and architectural elements were adorned with symbols of military glory, such as gilded images of arms and horses.

Designed by Apollodorus of Damascus, a famous architect and engineer, the column and its associated structures epitomized Roman architectural and engineering excellence. Apollodorus, who also constructed the famed Danube bridge, collaborated closely with Trajan.

While Trajan was more a military leader than an art connoisseur, his appreciation for monumental scale and grandeur is evident in these projects.

Detail of a bireme Roman galley ship in Trajan’s Colun in Rome. Credits: BGStock72, by Canva

The column itself served not only as an artistic miracle but also as Trajan’s tomb, housing his ashes—an exceptional honor in Roman tradition. Its spiraling bas-reliefs depict the emperor’s military campaigns, particularly the conquest of Dacia. These detailed scenes provide a rare visual narrative of Trajan’s life and accomplishments, as few written histories about him survive.

Historians like Pliny the Younger and poets such as Caninius Rufus left limited records, and many accounts of Trajan’s reign are fragmentary or lost. Trajan’s Column is not merely a testament to Roman military achievements but also a valuable historical artifact. It offers insights into the emperor’s character and the significance of Dacia, one of Rome’s last great conquests. Although the province was later abandoned by Hadrian, the column endures as a lasting symbol of Roman art, engineering, and imperial ambition.

Trajan: From Military Leader to Rome’s “Optimus” Emperor

Trajan, born around 53 CE, rose through the ranks of the Roman military, gaining invaluable experience under his father’s command during campaigns like the Parthian War. He served as a military tribune, praetor, consul, and governor in key regions such as Spain and Germania Superior.

His ability to manage both military and civil affairs, combined with his popularity among the legions, led to his adoption by Emperor Nerva, ensuring a stable succession.

Roman Emperor Trajan statue detail. Credits: Crisfotolux from Getty Images, by Canva

Known for his engineering prowess, Trajan left lasting legacies in military infrastructure, including the town of Ulpia Trajana, bridges over the Rhine and Danube, and colonies like those at Hochst and Baden Baden. These projects showcased his strategic vision and efforts to secure the empire’s borders.

Upon his entry into Rome in 99 CE, Trajan’s humility and approachability set him apart. He refused the typical exactions from provinces, walked into the capital on foot without guards, and engaged warmly with citizens and senators alike. His wife, Plotina, and sister, Marciana, also upheld his ideals, contributing to his legacy of magnanimity.

As emperor, Trajan spent two years in Rome implementing reforms, curbing corruption, reducing the power of the Praetorian Guard, and earning the title Optimus— “the Best.” This unique title reflected his exceptional leadership and was not passed to any other emperor. In the fourth year of his reign, Trajan embarked on his Dacian campaigns, driven by a belief in Rome’s mission of conquest and the necessity of military achievements to legitimize his rule, a sentiment echoed by leaders in later eras.

The Dacians: A Formidable Foe and Strategic Prize

The Dacians were a powerful and advanced people, distinct from Rome's German allies and tributaries. Skilled in metallurgy and warfare, they had gained military experience during their conflicts with Emperor Domitian's legions, acquiring Roman war machines and expertise through force or bribery. Despite lacking armor, they fought bravely in their traditional linen tunics and cloaks, relying on their natural resources and strategic fortifications.

Originating from the Getae, who were known for their proximity to Greek civilization, the Dacians had crossed the Danube and established a vast domain spanning Wallachia, Transylvania, Moldavia, and parts of Hungary. Their capital, Zarmizegethusa, was fortified on a rocky prominence in the Carpathian Mountains, surrounded by fertile lands and formidable mountain passes like the Iron Gate and Rothenthurm, making it an easily defensible region.

The Dacian territory was rich in resources, including abundant pastures for livestock and valuable mines of gold, silver, and iron. These natural riches, coupled with the region's strategic importance as a frontier defense, made Dacia a highly desirable conquest for the Roman Empire. (A description of the Trajan column, by John Hungerford Pollen)

Trajan's Column and the Testament to an Emperor's Legacy

In A.D. 117, Emperor Trajan, suffering from partial paralysis and dropsy, left his army in Syria to return to Italy. His journey was cut short by illness, and he passed away on 8 August in Selinus, Cilicia. His body was cremated, and his ashes were transported to Rome by his returning army.

These ashes, sealed in a golden urn, were placed in the base of the magnificent Column in his Forum—a unique honor for an emperor, as burials within the city were usually forbidden.

Trajan’s Column base in Rome, Italy. Credits: piola666 from Getty Images, by Canva

While the ashes were stolen during the Middle Ages, the Column still stands proudly in the heart of modern Rome, a celebrated monument of the Roman world. Although Trajan's Column has long been a subject of admiration, scholarly attention has largely concentrated on the narrative and historical elements of its spiraling frieze or its original context within the Forum.

What explains the Column's unconventional design and decoration, often viewed as unsatisfactory? And how did its designer use architecture and sculpture to immortalize the emperor's memory? By examining the Column as a work of mortuary art, we can have a fresh perspective on one of Rome’s most iconic landmarks.

Towering 150 Roman feet (44.07 meters), the Column features a sculpted base adorned with weapons and trophies, and a spiraling narrative frieze along its shaft. Atop its Tuscan capital once stood a gilded statue of Trajan, which was replaced after a lightning strike destroyed it.

The narrative frieze likely drew inspiration from illustrated scrolls or festival fabric wound around columns and is believed to be based on Trajan's account of the Dacian campaigns, Dacica. Since Trajan's written work is nearly lost, the Column serves as a rare visual record of the wars. Scholars, however, often critique the frieze for its viewing challenges, requiring observers to crane their necks upward and circle the Column repeatedly to follow its narrative.

There is debate over the Column's intended purpose. While Trajan's ashes were interred beneath it—an extraordinary honor granted posthumously by the Senate—it's unclear whether this sepulchral function was planned from the outset. Three possibilities emerge:

- It was initially conceived as an honorary monument and later repurposed as a tomb,

- It was redesigned to include a funerary function during construction,

- Or it was always intended to serve as Trajan’s burial site.

Whatever its origins, the Column stands as both a commemorative masterpiece and a unique repository of Trajan's imperial legacy.

Amanda Claridge, a scholar of Roman archaeology and professor of Roman archaeology at Royal Holloway, University of London, suggested that Trajan's Column may not have included its spiraling frieze during Trajan's lifetime, as its design is unusually intricate and may have been added later under Hadrian when the Column became Trajan's tomb.

The Column's base contains a chamber that resembles Roman funerary altars, featuring traces of a bench or altar and a bracket likely holding Trajan's golden urn, hinting at an original funerary intent. The Column's function aligns with traditions of honoring foundational heroes by burying them within city walls, as seen with Alexander the Great.

Trajan's decision to rest within the pomerium—a rare and presumptive act—distanced him from the Flavian emperors and evoked parallels with Julius Caesar's commemorative column in the Forum. Scholars argue that Trajan disguised his future tomb as a victory monument, revealing its sepulchral significance only upon his burial.

Sculptural elements throughout the Forum reinforce this dual purpose. Decorations of griffins, putti, and tauroctonous Victories symbolize both military power and apotheosis, drawing from funerary and triumphal traditions. This purposeful ambiguity in the Forum’s design reflects Trajan's intent to celebrate his achievements while cementing his legacy as both a victorious leader and a venerated hero in Roman memory. (The Politics of Perpetuation: Trajan's Column and the Art of Commemoration, by Penelope J. E. Davies)

Mapping Imperial Conquest Through Landscape and Narrative

Pliny the Younger’s Panegyric describes Trajan’s domination of Dacia as an almost supernatural triumph over geography itself.

“Though he be defended by the seas between, the mighty rivers or sheer mountains, he will surely find that all these barriers yield and fall away before your prowess, and will find that the mountains have subsided, the rivers dried up and the sea drained away, while his country falls a victim not only to our fleets but to the natural forces of the earth!”

This theme resonates powerfully in the reliefs of Trajan’s Column, which depict the emperor’s campaigns against the Dacians in a sprawling, spiraling frieze. The 190-meter-long narrative features over 2,600 figures and more than 300 structures, seamlessly woven into a cartographic-like portrayal of the terrain of southern Europe.

The landscapes—mountains, rivers, forests, and forts—are not mere backdrops but integral elements of the story, underscoring the Roman conquest of both people and land. Strikingly, the reliefs emphasize engineering feats over battle scenes. Roman soldiers are depicted building roads, constructing forts, and traversing challenging terrain.

These visuals highlight the critical role of military surveyors and engineers, whose work transformed enemy lands into Roman provinces. This transformation reflects a broader Roman imperial ideology, as geography and conquest were intertwined. Roman generals, like Trajan, documented their campaigns in commentarii, fusing military and geographical objectives. These writings, including Trajan’s lost Dacica, likely inspired the reliefs’ design.

The Column’s frieze functions as both an expansive map and a geographical treatise, illustrating the Roman mastery over terrain.

Details of Roman military tactics in Emperor Trajan’s Column. Credits: YinYang from Getty Images Signature, by Canva

Drawing on the cultural geography of writers like Strabo, the reliefs blend continuous narrative with topographical precision, conveying Rome’s imperialist vision. This combination of cartography, engineering, and narrative exemplifies how the Column’s designers used landscape as a tool of persuasion, linking conquest to the very reshaping of the earth.

A Testament to Leadership and Triumph

Both Pliny the Younger and Dio Cassius portray Trajan as a hands-on leader, deeply involved in every aspect of the Dacian campaigns, from strategy to construction and land transformations. This active engagement is vividly represented in the Column, where Trajan appears frequently, emphasizing his presence and command.

The Column’s creation reflects this direct involvement, with Apollodorus of Damascus, the campaigns' chief engineer and later the architect of Trajan’s Forum and Markets, likely serving as the mastermind behind the relief design. Additionally, Balbus, the lead military surveyor, contributed his expertise through an illustrated commentary, enriching the imagery with detailed accounts of the campaigns.

This collaborative effort mirrors a modern military engineer producing a comprehensive documentary after returning from a mission. The Column’s innovative helical frieze employs a continuous landscape, integrating topography as a central theme. This emphasis on land and its transformation traces back to a long tradition of Roman triumphal imagery, which combined battle scenes with quasi-cartographic elements.

Such visuals, documented since the Republic, celebrated the virtus (courage and excellence) of commanders. Triumphs displayed painted panels, banners, and models showing devastated landscapes, demolished fortresses, and conquered cities, as noted by Josephus in his account of the triumph of Titus and Vespasian. Pliny himself envisioned similar scenes in Trajan’s triumph, depicting the spoils and prisoners as testaments to Roman victory.

These triumphal images, which sometimes incorporated maps, laid the groundwork for the narrative quality of the Column’s reliefs, translating moving depictions of conquest into a monumental, enduring celebration of Roman dominance.

Pliny writes to a friend:

‘It is excellent to write of the Dacian War. You will describe new rivers set flowing over the land, new bridges built across rivers, and camps clinging to sheer precipices; you will tell of a king driven from his capital and finally to death, but courageous to the end..’

Pliny highlights the connections between Trajan’s Column, Roman conquests, and ancient practices of geography and cartography. The Column’s reliefs reflect the achievements of military surveyors and engineers, whose work during war and peace shaped the Forum of Trajan and the broader Roman worldview.

Inspired by geographical writers, the reliefs intertwine history and geography, depicting Roman soldiers and their constructions across a vast landscape, akin to a periplus voyage. This imagery serves as a powerful metaphor for Roman conquest, illustrating the process of claiming and integrating distant lands into the empire.

The reliefs also symbolize the viral spread of Roman culture, with marching camps and forts depicted as "little Romes," akin to the network of linked cities on the Peutinger Table. This expansionist ideology, central to Roman policy since Augustus, is expressed through construction and control. Augustus boasted of transforming Rome from a city of clay to one of marble, but Trajan surpassed even him with the grandeur of his Forum, described by Ammianus Marcellinus as unparalleled in magnificence.

Through its reliefs, Trajan’s Column encapsulates the empire’s expansion to its maximum territorial reach, serving as a visual testament to Rome’s ideology of conquest and its enduring legacy. (The Column of Trajan in the light of ancient cartography and geography, by John Stephenson)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: