The Roman Supernatural: Magic, Omens, Haunted Houses, Ghosts and Rituals

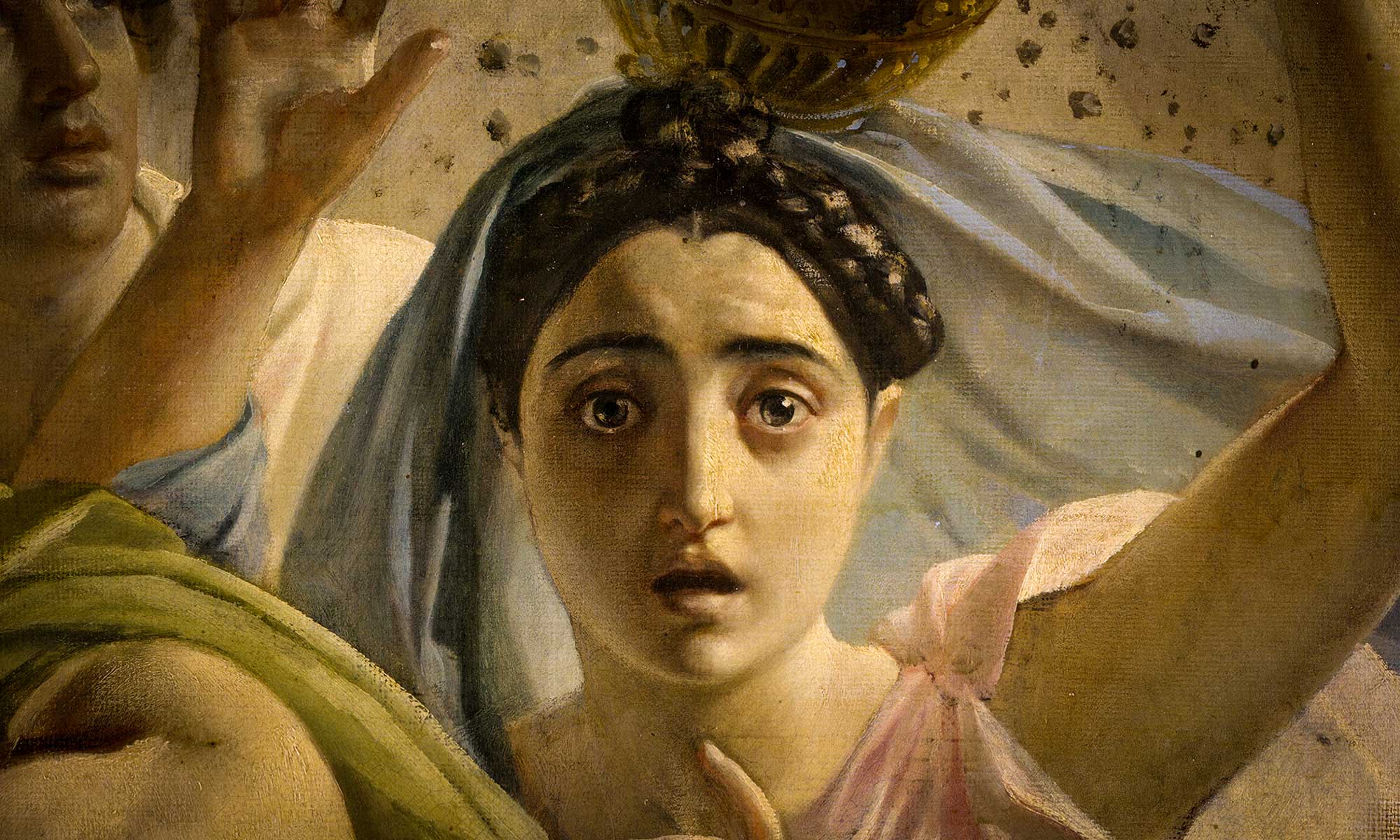

In a world ruled by signs and shadows, the Romans saw meaning in every tremor and whisper. Fear was not weakness but wisdom—their way of reading a universe alive with gods, ghosts, and omens.

In the world of ancient Rome, fear was not an absence of courage but a form of understanding. Every shadow carried a warning, every rustle of wind a divine whisper. The Romans lived among invisible forces—gods, ghosts, curses, and omens—that blurred the boundary between the natural and the supernatural.

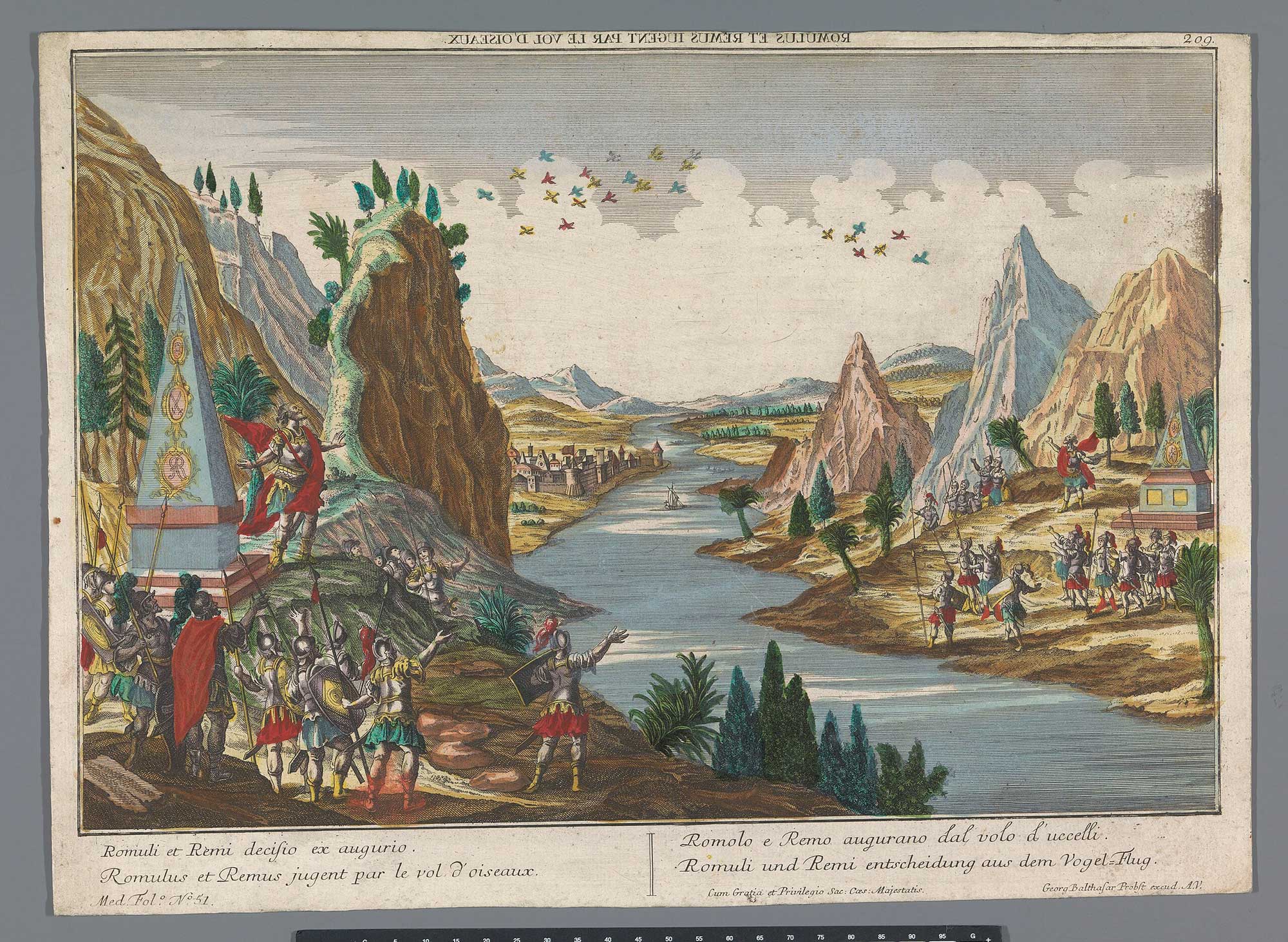

To them, unseen powers shaped the course of empires as much as they governed the fate of a single household. Their world was not defined by disbelief, but by the uneasy conviction that nothing happened without cause, and every sign—whether flight of birds or flicker of flame—demanded to be read.

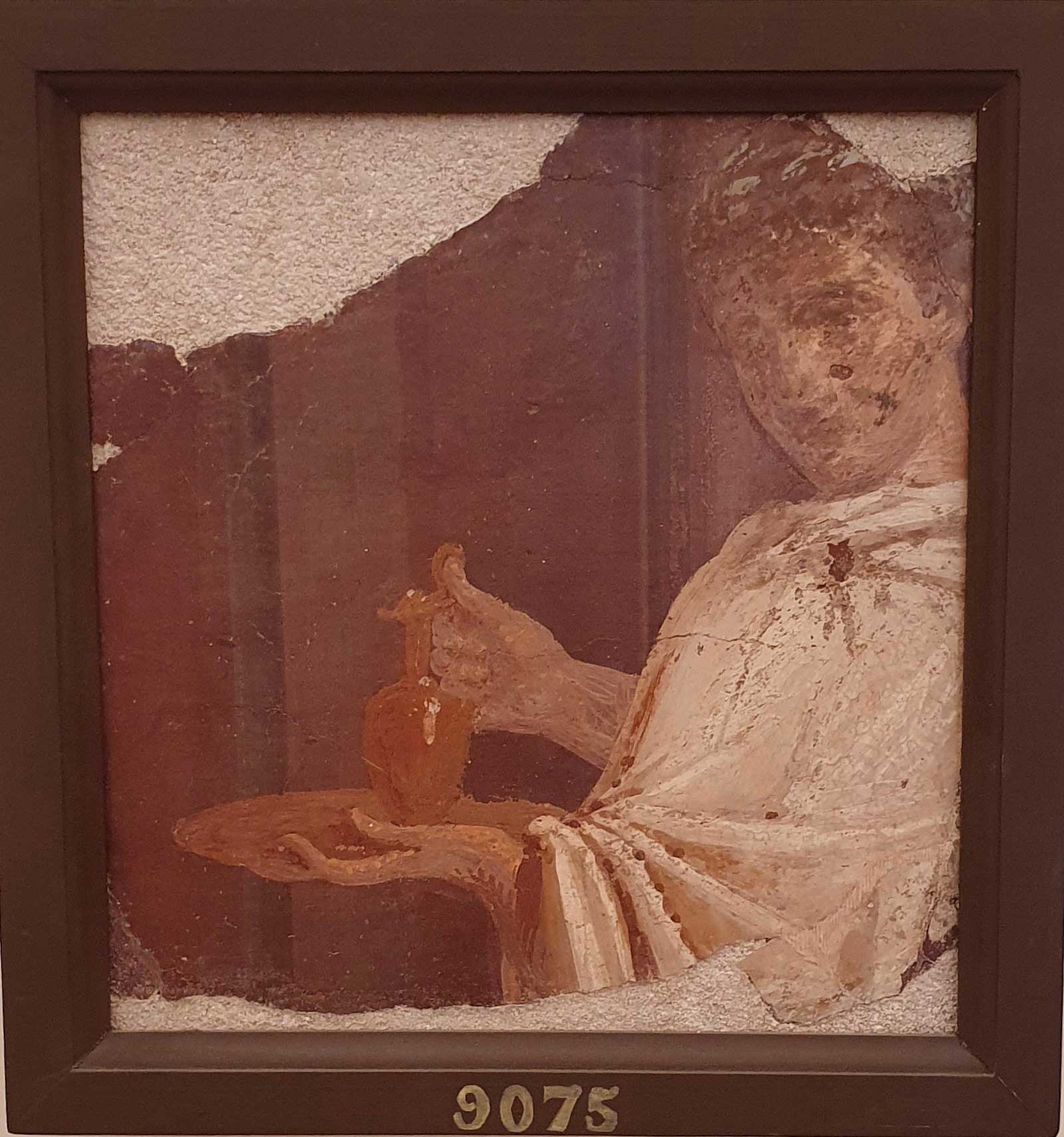

The Romans lived in a world where the divine and the earthly constantly touched. They feared eclipses, trusted auguries, and sought meaning in every living and lifeless thing—the eyes of animals, the course of birds, the crackle of a flame. When a statue seemed to sweat, when blood appeared at a doorway, when lightning struck a temple, the whole state shuddered and turned to the Sibylline Books for counsel.

No omen escaped attention, no prodigy passed without interpretation, no misfortune went unexplained by divine will. Priests stood as translators of the mysterious; magistrates guarded the balance between heaven and earth; and citizens themselves became players on a sacred stage, where dreams, visions, monsters, and signs each had their appointed part. The seer bent over the entrails of sacrifice, the augur traced his staff across the sky, and the censor recorded every prodigy as if cataloguing the misdeeds of the gods themselves.

Messages from the Heavens: How Romans Interpreted the Unseen

To the Romans, the gods spoke through signs. These divine messages—prodigia and omina—formed a sacred vocabulary through which heaven revealed its pleasure or anger. A prodigium was not merely a marvel, but a rupture in the natural order, an event so strange it demanded interpretation: a cow giving birth to a lamb, a rain of stones, a temple struck by lightning.

An omen, by contrast, could be drawn from a word, a gesture, a chance encounter. The universe, to Roman eyes, was never silent. It whispered through accidents and coincidences, each carrying a hidden intent.

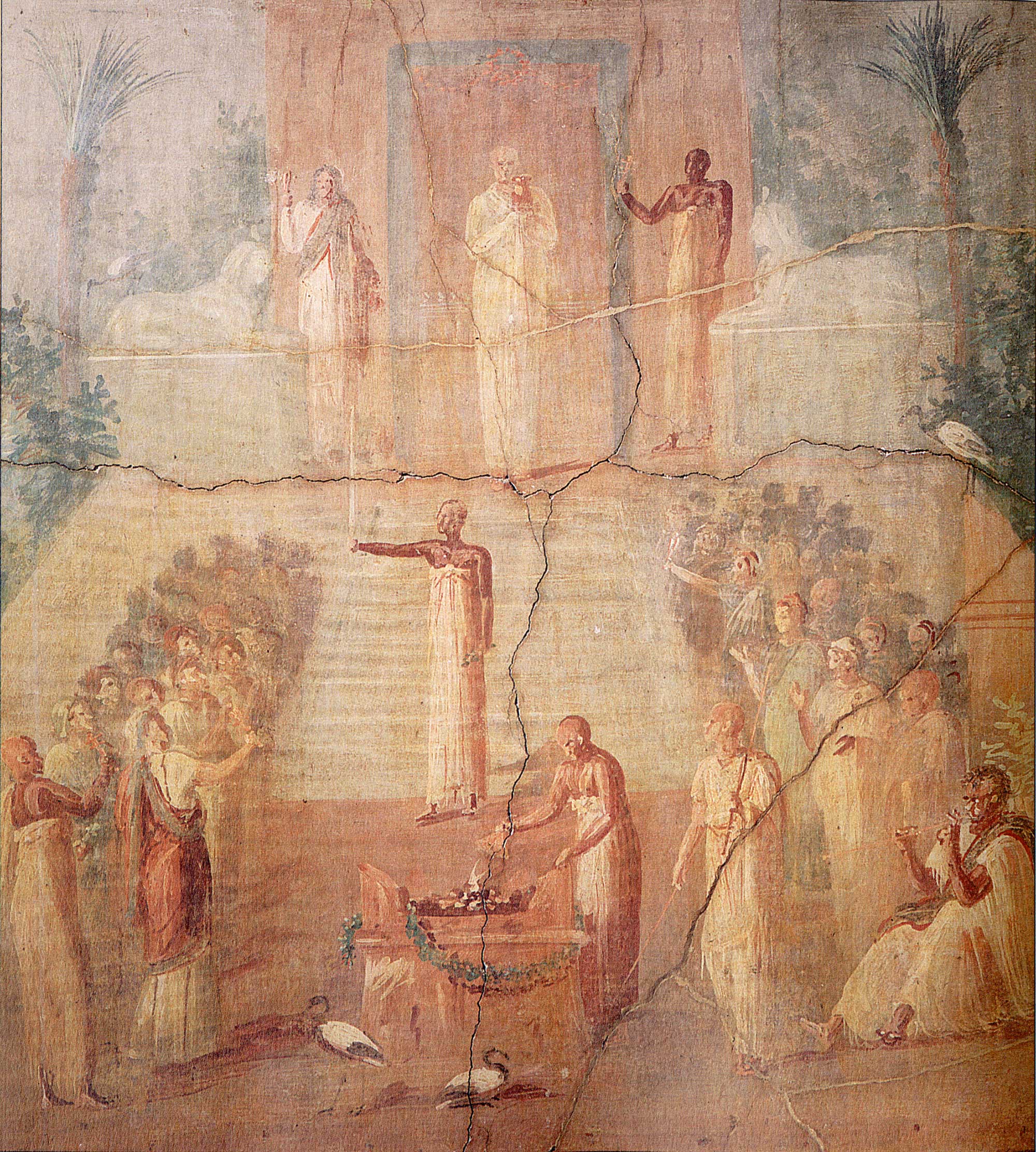

Every unusual occurrence carried weight, for it was believed that the gods constantly negotiated with humankind through signs. The task of interpreting these divine communications fell to priests, augurs, and magistrates, who maintained the fragile balance between men and gods. They did not see their role as mystical but as civic duty: to decode the will of the divine and restore harmony when it was disturbed.

When the extraordinary broke into the ordinary—when rivers flowed backward or statues bled—the city itself became the theater of divine communication. Each anomaly demanded response: rituals of purification, sacrifices, and expiations. Rome’s safety depended on recognizing and answering the voice of the gods. The prodigium was not only a warning but an invitation—a summons to act, to realign the moral and cosmic order.

Such signs were never taken lightly. To ignore a prodigium was to risk catastrophe; to misinterpret an omen was to offend the gods. The Roman world rested on the conviction that every event, no matter how small, participated in a greater pattern of meaning. In this sacred dialogue, the gods spoke through storms and silences alike—and Rome, through her priests and augurs, learned to listen.

When the Earth Trembled and the Sky Burned: Rome’s Search for Meaning in Disaster

To Romans, natural catastrophes were never blind accidents. Every trembling of the earth, every eclipse that darkened the sun, every streak of fire across the night sky carried a message from the gods. The world above and the world below were bound in dialogue, and Rome’s duty was to listen.

When the ground shook, it was not geology but theology that demanded attention. Temples opened their doors unbidden; mountains split; the Tiber reversed its flow—each phenomenon was a line in the divine script that magistrates and priests worked to decipher.

Earthquakes terrified the ancients because they seemed to shatter the boundary between realms. As the earth convulsed, it was believed that the underworld rose to speak. The Senate would decree expiations, sacrifices were offered, and temples purified to restore cosmic order. A quake near the Capitoline was not just a tremor beneath the city; it was the gods themselves stamping their displeasure on Rome’s heart.

Eclipses struck even deeper fear. As the moon turned red or the sun vanished at midday, Romans saw not the play of celestial bodies but a withdrawal of divine light. They read in those shadows warnings of political upheaval or the death of rulers.

The populace would fill the streets, clanging bronze vessels and shouting prayers to coax back the sun. In these moments, the entire city became an altar of supplication, reaffirming its dependence on divine favor.

Meteors, comets, and unexplained fires in the heavens inspired awe and anxiety alike. A single streak of light could portend the fall of a dynasty. When fiery spears or phantom armies were reported in the skies, the state turned to the Sibylline Books and the college of priests for guidance.

Every celestial disturbance, however small, was absorbed into the political life of the Empire. The heavens and the Republic reflected one another—what trembled above echoed below.

In this cosmology, Rome stood at the center of an unstable universe, where the gods spoke through storm and flame. Understanding these messages was both a science and a sacred duty. For the Romans, ignorance was peril: to misread a sign was to invite disaster; to interpret it correctly was to keep chaos at bay.

The Art of Knowing the Unknowable: Dreams, Oracles, and Prophecy in Roman Life

Divination lay at the core of Roman religion. It was not superstition, but a system through which the divine will was sought, questioned, and, when possible, understood.

The Romans believed that the gods constantly communicated with humankind—through voices, dreams, movements of birds, the behavior of animals, or the subtle patterns of the stars. To ignore such communication was to break the pact that bound the city to its deities.

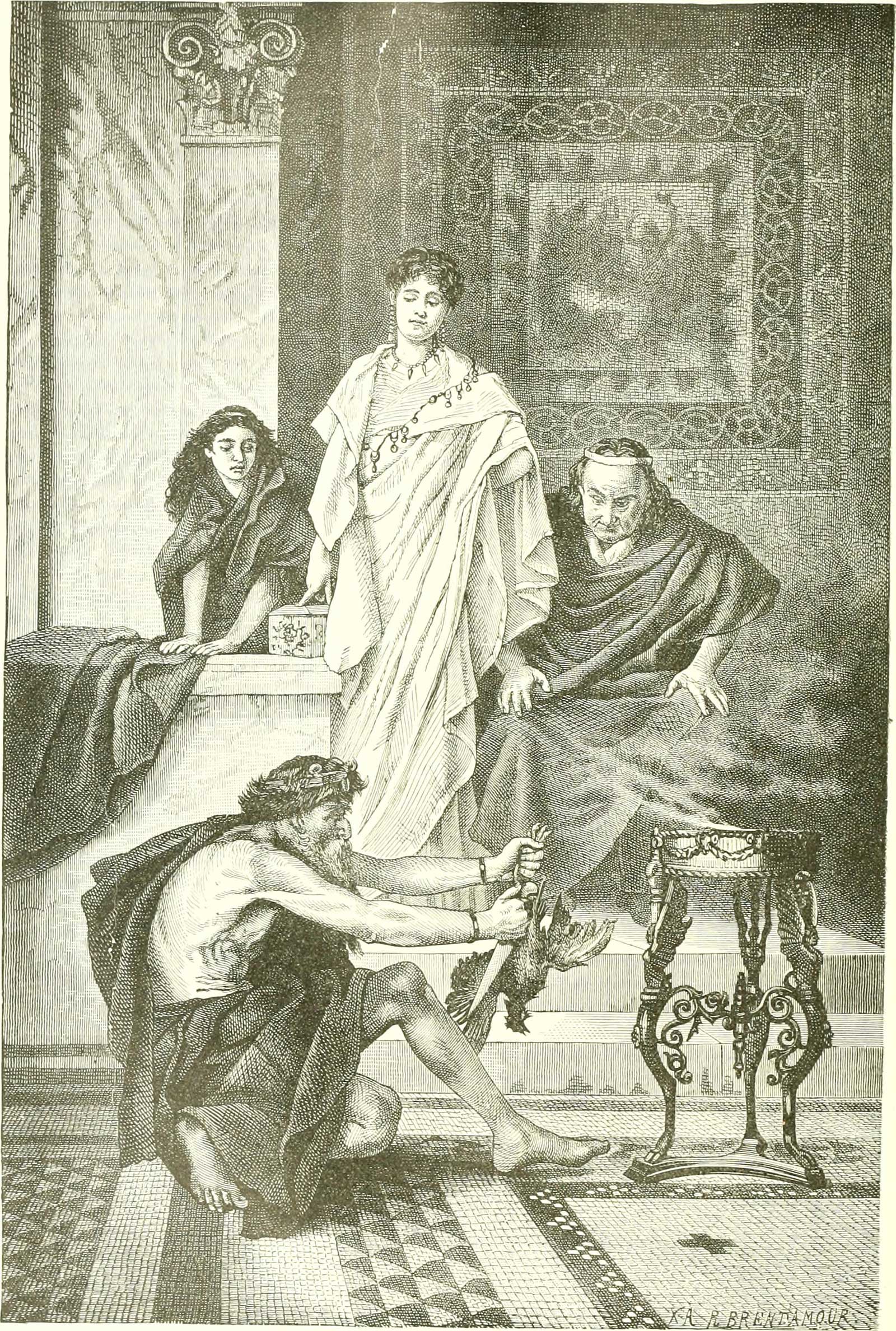

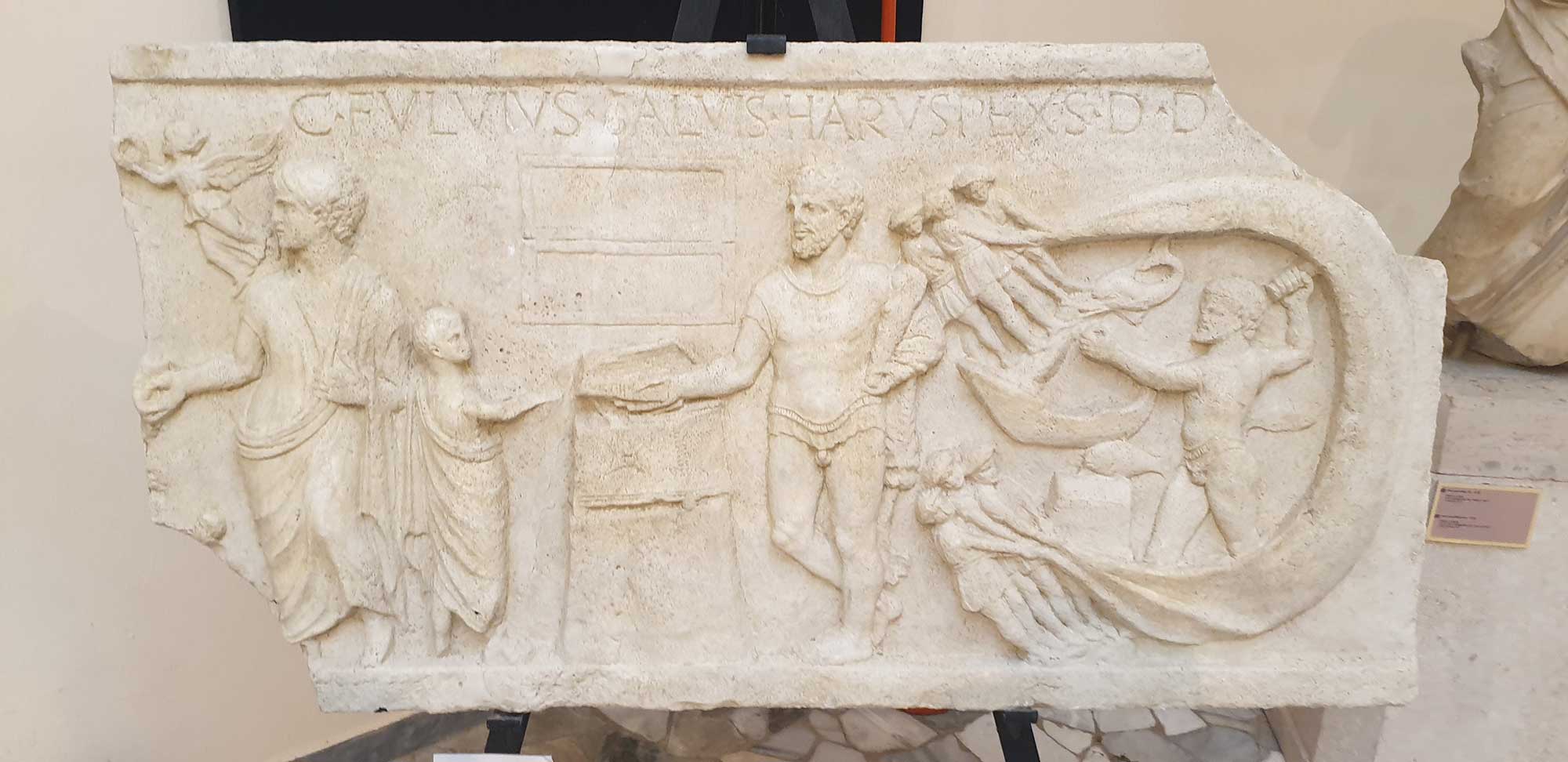

The art of divination was divided into observation and inspiration. Some interpreters read the physical world—augurs (Roman priests who interpreted omens to understand the will of the gods) studied the flight of birds and the direction of lightning, while haruspices (a haruspex[a] was a person trained to practise a form of divination called haruspicy in the religion of ancient Rome, the inspection of the entrails[c] of sacrificed animals, especially the livers of sacrificed sheep and poultry) examined the entrails of sacrificial victims for signs of divine pleasure or wrath.

Others received knowledge directly through visions and trances: prophets, dreamers, and oracles, who acted as vessels through which the gods spoke. Both forms were regarded as essential, for they revealed two dimensions of divine truth—the signs given by nature and the messages sent through spirit.

Dreams occupied a special place in this dialogue. The sleeping mind, free from the distractions of the waking world, was thought to be open to the gods. Dreams could warn, guide, or foretell events, and they were often verified through rituals at temples or shrines. The dream of a general before battle, or of a senator before a vote, could alter the course of Roman policy. Some dreams were so vivid they were recorded as public prodigies, preserved alongside omens and portents as matters of state.

Oracles, meanwhile, offered a structured approach to divine consultation. Whether through the Sibylline Books, the Delphic priestesses, or local shrines across Italy, the gods were believed to speak through chosen intermediaries. Their words, often cryptic, were interpreted by priests and magistrates who translated divine riddles into political action. A single phrase could determine war or peace, expansion or retreat, depending on how it was read.

Prophecy completed this triad. The prophetic voice could come from inspired individuals who claimed divine possession, or from poets whose verses seemed to channel fate. Prophecy was both feared and revered, for it blurred the boundary between mortal and divine will. Some rulers sought to suppress it, others to control it—but none could escape its power.

Through dreams, omens, and inspired speech, the Romans believed they could glimpse the pattern of destiny itself. Divination, in all its forms, was not an escape from reason but a complement to it: a disciplined attempt to make sense of the unseen. It was the art of interpreting silence—the way by which Rome sought to read the mind of the gods.

Whispers of Power: Magic, Curses, and Forbidden Rituals in Ancient Rome

Beneath the ordered surface of Roman religion ran a current of fear and fascination for the unseen forces that governed fate. The Romans distinguished carefully between lawful rites sanctioned by the state and the shadowed practices that lay beyond it.

Magic, though often condemned, was inseparable from Roman life—feared, forbidden, and yet constantly sought. It was the secret art of bending divine will to human desire.

Where official religion appealed to the gods for protection, magic sought to compel them. The magician and the priest might use the same words, the same gestures, even the same offerings, but their intent diverged sharply.

The priest worked in harmony with divine order; the magician trespassed upon it. This transgression made magic both dangerous and powerful—an act of rebellion against the celestial hierarchy that structured Rome’s world.

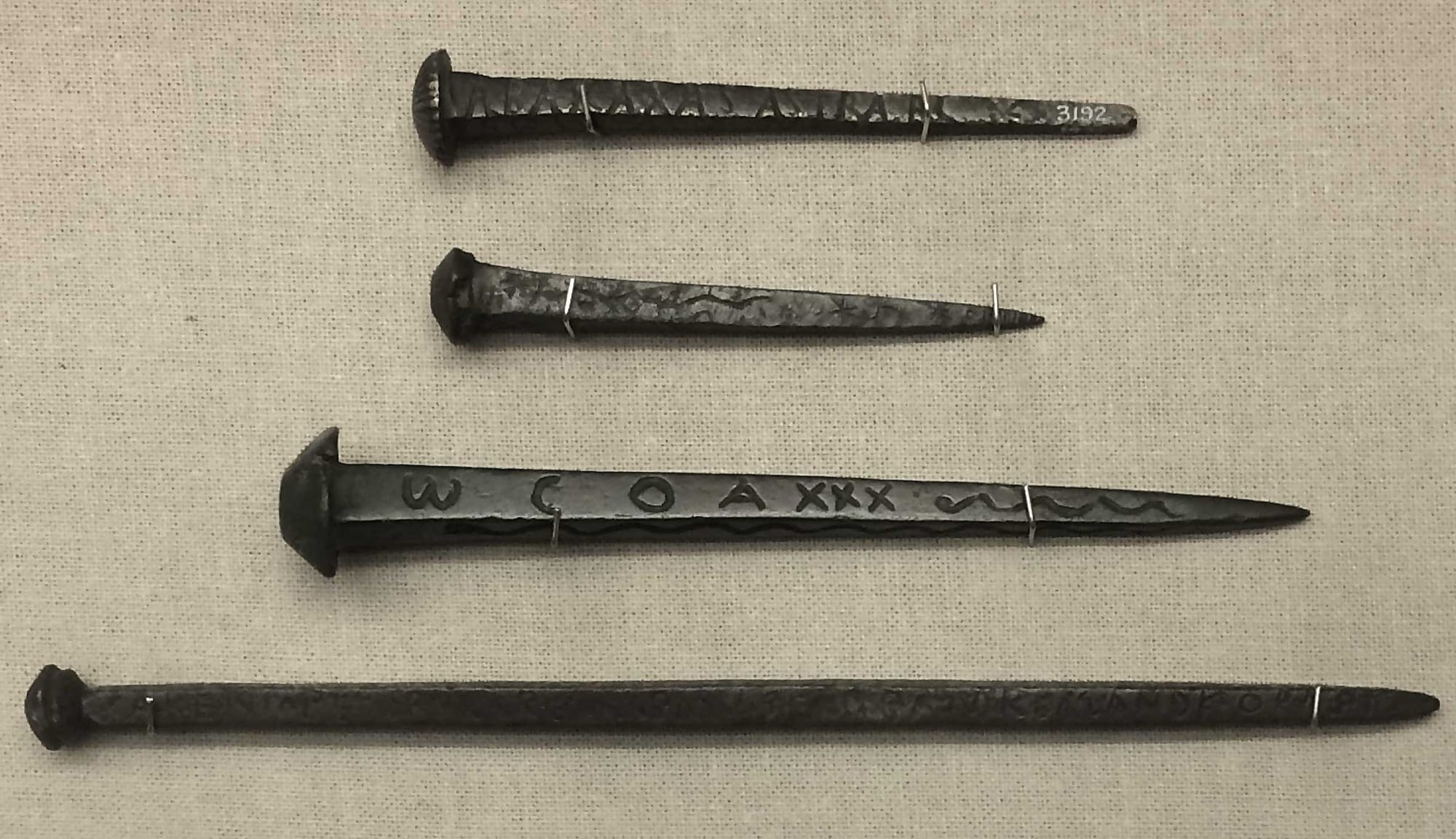

Curses were among the most common expressions of this forbidden craft. Inscribed on lead tablets and buried in graves, wells, or arenas, they called upon infernal powers to torment enemies. The language was formulaic yet personal, a blend of legal precision and supernatural menace.

Names were etched with care, sometimes with hair or nail clippings to bind the spell to its victim. The gods invoked were not Jupiter or Mars but darker beings—spirits of the dead, avengers who dwelt below.

Roman curse tablets, with the curses scratched on lead. Credits: Rijksmuseum, CC BY-3.0 NL, Getty Museum

Such acts reflected a world in which divine justice was uneven and human passions demanded their own redress. When law failed or fate seemed unjust, the curse became a weapon of last resort.

Even the educated, who mocked superstition, might secretly turn to it in desperation. Archaeology has uncovered hundreds of these tablets across the empire, testimony to a society where fear and faith intertwined.

Dark rituals also flourished on the margins of legitimacy—rites of love and compulsion, of healing and harm. Magical papyri, later preserved in Egypt, reveal mixtures of Greek, Egyptian, and Roman traditions: invocations, incantations, and diagrams meant to summon spirits or influence the living.

Some magicians claimed divine lineage; others masqueraded as priests. Their rituals were nocturnal, their tools drawn from the natural and the grotesque—blood, wax, ashes, and herbs gathered under specific constellations.

The state treated such practices with suspicion, not only for their impiety but for their political danger. Magic blurred the line between personal will and divine command; to control fate was to challenge the emperor himself, who alone claimed divine favor.

Laws against maleficium—evil magic—were harsh, and trials for sorcery often concealed charges of treason. Under Augustus and later emperors, astrologers, necromancers, and magicians were expelled or executed, yet their art endured, carried in whispers and hidden charms.

For the Romans, magic embodied both terror and temptation. It promised control in a world ruled by capricious gods, offering power to the powerless and vengeance to the wronged. But every spell carried a shadow, every invocation a risk. To speak the language of the gods without permission was to invite their wrath—and yet, countless Romans could not resist the call.

Restless Shadows: Ghosts, Cursed Houses, and the Haunted Corners of Rome

The Romans lived among their dead. Tombs lined the roads that led into every city, and the memory of ancestors filled both household shrines and the imagination of the living. Yet beyond this accepted communion between the worlds of the living and the departed lay a darker realm—the realm of spirits who refused to rest.

These were the lemures and larvae, wandering shades born of violent deaths, improper burials, or unavenged crimes. Their presence chilled both private homes and public streets, reminders that the boundaries between life and death were thin and easily disturbed.

Ghosts appeared not only as phantoms of terror but as moral messengers. Their return was rarely meaningless. A murdered man’s spirit might haunt his killer until justice was done; a restless shade might demand the proper rites to ensure peace.

The Lemuria, an annual festival held in May, was devoted to appeasing such beings. At midnight, householders rose barefoot, tossing black beans behind them as offerings to the dead, reciting incantations to banish the lurking shadows. Ritual words, spoken nine times, were thought to silence the invisible guests. In this quiet exchange, the living acknowledged their fragile truce with the dead.

But some places, the Romans believed, were beyond purification. Certain houses bore reputations so ominous that they could not be sold except to the desperate. Ancient writers tell of doors that creaked without wind, chains clattering in empty rooms, and pale figures that beckoned silently in the night.

Even great men—philosophers and senators—recorded such stories. Pliny the Younger recounts the tale of an Athenian house where an old man, shackled and gaunt, appeared to every tenant until the remains of a bound corpse were found and properly buried. Such accounts, preserved by rational minds, reveal not gullibility but a cultural truth: even in an age of logic, fear of the unseen endured.

There was at Athens a large and roomy house which had a bad name, so that no one could live there.

In the dead of night a noise like the clashing of iron was frequently heard, and if you listened more attentively, a sound of chains; at first, it seemed at a distance, but soon it approached nearer and nearer.

Immediately after, there appeared a spectre, an old man, emaciated and squalid, with a long beard and dishevelled hair, rattling the chains on his feet and hands.

The inhabitants consequently passed sleepless nights under the most dreadful terrors imaginable; this want of rest produced disease, and their growing fears ended in death.

Even in the daytime (when the spectre did not appear) the impression remained so strong upon their imaginations that they fancied they still heard the clanking of chains, and consequently their terror continued.

The house was at last deserted and left entirely to the ghost, thus it was advertised as being forsale or to let, in case anyone was so bold as to venture into it.

Athenodorus, the philosopher, came to Athens, read the bill, and, upon hearing the price was low, suspected some extraordinary reason for it, and was told the whole story.

Nevertheless, he rented the house and took up his lodging there.

In the evening he ordered his couch to be placed in the forepart of the house, and, having a light and his writing materials, he directed all his attention upon his studies to prevent his mind from being imposed upon by vain terrors.

The first part of the night passed in silence; at length the clanking of iron and the rattling of chains was heard.

He neither lifted up his eyes nor laid down his pen, but fortified his mind and continued to write.

The noise increased and advanced nearer, till it seemed at the door, and at last within the room itself.

He looked round and saw the apparition exactly as it had been described to him.

The ghost stood still and beckoned with its finger, as if inviting him to follow; upon which Athenodorus made a sign with his hand that it should wait a little, and again bent his head over his papers and his pen.

When he had finished his writing, he took up a light and followed it.

The spectre walked slowly, as if encumbered with its chains, and turning into the courtyard of the house, suddenly vanished.

Athenodorus, being thus left alone, marked the spot with some grass and leaves, and the next day he gave information to the magistrates, who ordered it to be dug up.

There they found the bones of a man bound with chains.

These were collected and buried at the public expense, and after the rites of burial, the ghost appeared no more.

The house was haunted no longer.

Pliny the Younger, in Letter 7.27 (to Licinius Sura)

Haunted spaces were not confined to houses. Entire districts, battlefields, and stretches of countryside were said to echo with voices of the unquiet dead. The Romans feared crossroads, tombs without names, and places struck by lightning—all thought to open pathways between worlds.

In these liminal spaces, the veil between the living and the dead thinned, and unseen presences were free to wander. Travelers avoided them at night; farmers left offerings to avert misfortune.

To the Romans, haunting was not merely superstition—it was a form of disorder. A ghost signaled unfinished business between mortals and the divine. Every haunting was, in essence, a prodigy demanding expiation.

The response was ritual: purification with fire, libations of milk and honey, or the consecration of the ground. Even emperors took such matters seriously, ordering temples built where lightning had struck or where the dead had stirred too close to the living.

The fear of haunted places expressed a deeper anxiety about the fragility of order itself. Rome’s greatness rested on the belief that the world was governed by law—human and divine. Ghosts defied both. They were the residue of injustice and neglect, the voices of those Rome had failed to appease. To walk in a haunted house, to hear a chain in the night, was to be reminded that peace, whether civic or cosmic, required constant vigilance. (Mysteries and Fears in Ancient Rome, by Claudio Romano)

Magic: The Shadow Religion of Rome

Beneath the Roman world’s ordered rites, there pulsed a quieter faith—one that spoke the same sacred language yet turned it inward. The line between religion and magic was perilously thin: both sought communion with the divine, but religion offered reverence, while magic dared to command.

To the state, the difference was one of loyalty. Religion was collective—it bound the community together under the watch of Jupiter and the emperor. Magic was private and subversive, practiced in secret and for personal gain.

The magician was therefore a dangerous figure: a solitary rival to the priest, an outsider who claimed power without authority. The same ritual gestures—a prayer, a libation, a sacrifice—could shift from holy to forbidden depending on the intent. What priests did openly, magicians did in shadows, and so both were feared and sought after in equal measure.

The law cast its judgment in harsh terms. Decrees such as the Lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis treated magicians as poisoners, for their craft was believed to kill without blade or flame. They could ruin crops, curse enemies, or twist the minds of the innocent.

It was designed to punish a broad range of acts considered threats to life or moral order—murder, poisoning, abortion, human sacrifice, and harmful magic—and remained in force for centuries, still cited in the age of Emperor Justinian in the sixth century CE.

According to later juristic commentaries, particularly those attributed to Paul, the statute set precise penalties according to both crime and social rank.

Those who prepared or sold love potions or abortive drugs faced relegation to the mines if of low status (humiliores), exile to an island if of higher rank (honestiores), and death if the substance caused fatality.

Those performing curses, binding spells, or acts of sorcery could be crucified or thrown to wild beasts, while those engaged in human sacrifice or blood offerings suffered the same fates—execution for the upper classes, death by beasts for the lower.

A professional magician or magus could be burned alive. Possession of magical books brought confiscation of property and the public destruction of the texts; the well-born were exiled, the poor executed. Even healers whose remedies caused death faced death or banishment, depending on class.

The law replaced older and more archaic penalties such as the poena cullei—the gruesome punishment of being sewn into a sack and thrown into a river—with more standardized methods of execution and exile.

Initially, banishment and confiscation of property were the chief sentences, but by the later empire capital punishment became common, with penalties differing between the social orders.

The law’s reach extended not only to those who poisoned or enchanted, but also to suppliers and manufacturers of lethal or harmful substances, holding them equally responsible. Its treatment of abortifacients aimed chiefly at protecting the mother’s life rather than the unborn child.

Over time, the law expanded its scope. Emperor Hadrian applied its penalties to those who performed castration, an act already restricted under Domitian, and Antoninus Pius extended it further to include the circumcision of males—with the sole exemption granted to the Jewish community.

Yet this fear also concealed fascination. The very senators who condemned sorcery sent for astrologers in private; generals carried charms into battle; emperors expelled magicians from Rome only to summon them again in secret. The language of magic—spells, omens, and signs—was too deeply woven into Roman thought to be silenced.

While laws condemned magic as subversion, the powerful rarely resisted its allure.

Tiberius executed astrologers yet practiced their art himself (Suetonius, Tiberius 69).

Nero, who expelled them from Rome, relied on his own court astrologer, Balbillus (Tacitus, Annals 14.9).

Pliny the Elder admitted that “no one is free from its fascination” (Natural History 30.3).

Generals like Marius and Sulla consulted prophets and carried amulets into battle (Plutarch, Lives)

Even as emperors issued decrees banishing magicians, the same figures reappeared in their courts (Cassius Dio, Roman History 49.43).

The empire denounced sorcery in public—but in private, its rulers and elites listened closely to the whispers of the occult.

Evidence of these private fears and hopes survives in the form of lead curse tablets, scratched with cramped letters and buried in wells, tombs, and sanctuaries. Their words are crude, emotional, and utterly human. A lover begs for affection to be returned, a merchant curses a rival’s tongue, a slave implores the spirits of the dead to avenge a cruel master.

These were acts of desperation more than malice. For those without power, the underworld offered justice when no court would listen. In this way, magic became the hidden law of the powerless—a way to speak when speech was forbidden.

But the world of magic was not entirely dark. Its rites also protected, cured, and blessed. Mothers tied charms around the necks of infants to ward off fever. Soldiers buried amulets near battlefields. Farmers whispered prayers over seeds and wine. Travelers carried inscribed gemstones to guard against storms and shipwrecks. Magic filled the space where faith met fear—an intimate dialogue with the unknown.

Rome’s suspicion of these practices was rooted as much in politics as in piety. Power over the invisible was power over destiny, and destiny was the emperor’s domain. A man who could summon spirits, read omens, or interpret the stars claimed a kind of authority the state could not easily control. The empire’s repeated expulsions of astrologers and necromancers reflected not disbelief, but fear of their influence. The cosmos, after all, was thought to mirror the city. To disturb one was to endanger the other.

Yet magic persisted through adaptation. When new religions arose, the old incantations and protections simply changed form. Prayers replaced spells, relics took the place of amulets, and blessings became the lawful echo of enchantments once whispered in secret. The gestures remained, their meanings recast under gentler names. Rome never fully escaped its enchantment with the hidden. What had once been forbidden found sanctuary in the rituals of faith that followed.

In the end, magic was not the enemy of Roman religion—it was its reflection. It spoke to the same fears and longings that filled the temples but offered a different kind of hope: the belief that a single voice, uttered in darkness, might alter the design of fate.

Beneath the empire’s order and reason lay a trembling acknowledgment of the unpredictable—a sense that the world was alive, watchful, and filled with signs waiting to be read. In that fragile balance between awe and anxiety, between law and mystery, the Romans built not one religion, but two: one for the gods of the state, and one for the restless spirits of the human heart. (Magic in the ancient world, by Fritz Graf)

From the trembling of temples to the whisper of charms, fear shaped the Roman soul as surely as faith did. The empire’s strength lay not only in legions and law but in its restless vigilance before the unseen—a civilization that never ceased to look for signs, even in silence.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: