The Forbidden Dionysian Mysteries: Why did the Roman Empire Persecute Christianity?

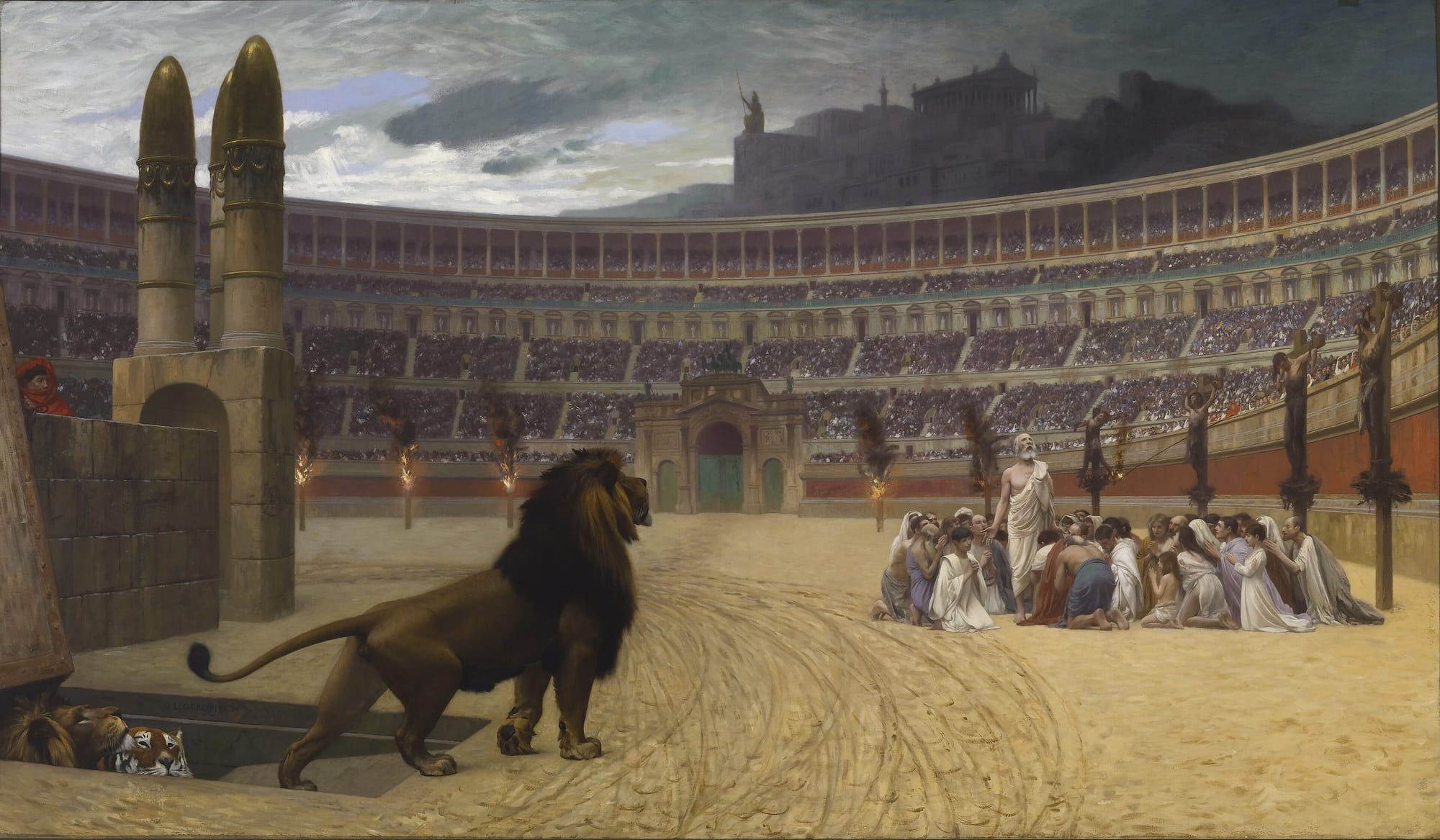

A historical event that has attracted the curiosity of most scholars and historians is no other than the Persecution of Christians. One cannot deny its intensity as well as its tremendous nature that lasted in so many different periods of the Roman empire from the 1st until the 4th century.

The cause of the Christian persecution is a subject that has been a debate for centuries. How is it possible that such a vast and ethnically as well as religiously diverse empire like the Roman one with so much tolerance for all other religions could impose such persecutions, showing immense cruelty to a seemingly harmless religion?

From Nero’s scapegoat of the Christians as responsible for the Great Fire to Decius’ persecution as well as with the Great Persecution of Diocletian, various Roman emperors used many pretexts at different periods of the Roman empire to impose their terror to the Christian community. But what was the main reason for this religion being so specifically targeted?

The ban on nocturnal meetings and the fear of Dionysian cults in Rome

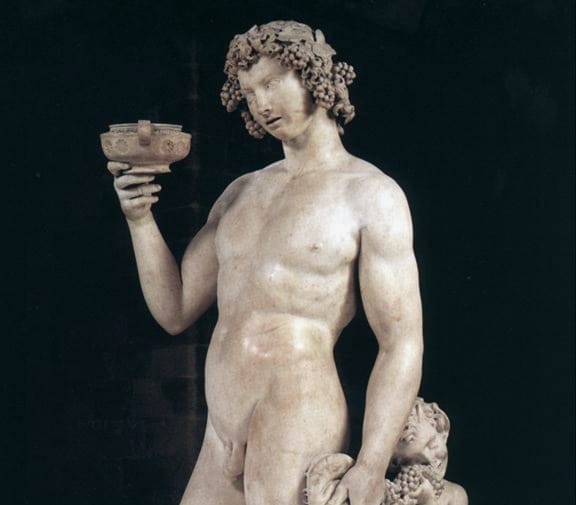

The early Romans would worship a deity equivalent to Dionysus. The worship of ‘’ Liber Pater’’ was inserted in the Roman Republic thanks to cultural contact with the Etruscans and South Italians. It was however mainly associated with the plebeians and was always viewed as suspect and degenerate by the Patrician elite.

The Roman aristocratic ideal demanded sober characters who respected norms and rules and their minds would dominate over emotions and instincts. And this ideal would be incompatible with the the cult of Liber Pater.

Nonetheless the Patricians tolerated it while at the same time associate it with the plebeians who apart from wine would most commonly consider this God to represent their liberties. What however the Roman Patrician elite would never tolerate would be the Dionysian mysteries and most specifically nightly occult rites.

The Romans in all their history always had a fear for all nightly secret associations. That was a law already established by Romulus in his Twelve Tables and would remain and make it to the imperial period. According to David Irving :

‘’ The causes and the pretexts of persecution may have varied at various periods; but there seems to have been one general cause which will readily be apprehended by those who are intimately acquainted with the Roman jurisprudence. From the most remote period of their history, the Romans had conceived extreme horror against all nocturnal meetings of a secret and mysterious nature.

A law prohibiting nightly vigils in a temple has even been ascribed, perhaps with little probability, to the founder of their state. The laws of the twelve tables declared it a capital offence to attend nocturnal assemblies in the city.’’ (Observations on the Study of the Civil Law, by Dr. Irving, Edin. 1820. p. 11.)

Accordingly, he adds that in the spirit of that law, the nocturnal assemblies of the early Christians must have made them objects of unusual suspicion, and exposed them to the scrutiny of the authorities. It was at night that they generally conducted their most solemn and sacred gatherings. In this respect, therefore, the Romans incurred no penalties unique to adherents of a new faith, but only such as were equally imposed on those who, while professing the public religion of the state, were nevertheless guilty of this clear breach of its laws.

Bacchus against Rome

But apart from the obvious reason that was the fear of the Romans for conspiracies, it was precisely its religious nature and the Dionysian elements that would trigger this hostility. Dionysus stands apart among the gods as the power of ecstasy, instinct, and emotion—the god who dissolves boundaries rather than enforcing them.

As protector of wine, he presides not merely over intoxication but over transformation itself. Wine is water transfigured: water, the primordial liquid from which all generation and corruption arise, mixed with etha-nol, a warm, fiery principle. In this sense wine mirrors blood, itself a fusion of water and fire, the substance through which life sustains and animates itself.

To drink wine is therefore not simply to escape sobriety but to participate in a cosmological process, a controlled descent into flux. As Nietzsche observed, in frenzy nature “uncovers its secrets”—revealing what remains invisible to the sober, Apollonian eye. This is why Heraclitus could identify Dionysus with Hades: both rule over transformation, dissolution, and return. In Dionysian vision, the dead may appear not as ghosts but as truths—what lies beneath form, order, and daylight reason.

The mysteries of Dionysus, including the myth of Dionysus Zagreus that also played a central role in the Eleusinian rites, enacted this truth with terrifying consistency. What occurred in these rites was the loss of personality and personal consciousness, surrendered to the ecstatic, unifying power of the god.

Ethics, dignity, identity, and honor—pillars of civic life—were temporarily stripped away, and each initiate submitted to the rule of his or her daimones, his/her instincts. In that dissolution came illumination: the light of Dionysus, where all distinctions collapsed. All became water, all became Dionysus; men and women, children and elders, slaves and free, poor and rich, kings and workers were rendered equal in the same sacred frenzy.

This was precisely what the Romans feared and despised. It was equality through dissolution, the annihilation of hierarchy, law, and stable identity, that made Dionysian occultism intolerable to a civilization built on order, control, and fixed roles. Dionysus threatened not morality, but the very structure of power itself.

In historical times, the figure of Dionysus lies at the heart of most socio-political and religious transformations. Dionysus is the god who not only guides individuals beyond customs, hierarchies, and social barriers, but, as “Dionysus Eleutherios,” provides the foundation for liberation from human constraints and the ascent of man to Olympus, as in the myth, achieving his “divinization.”

These characteristics influenced both democracy and monarchy—both political systems that, at least during the Republican period, were regarded with suspicion or even hostility by Rome. It is no coincidence that the democratic reforms in Athens began with the blessings of the Eleusinian priesthood, promoting Cleisthenes to the leadership of the city, who established Democracy in Athens in 507 B.C.

Monarchy and Democracy: The Roman Republic's Worst Enemies

Here it’s worth to note the difference between Republic and Democracy as polities. In essence, the difference between a democracy and a republic lies in both participation and orientation of governance. A democracy, in the Aristotelian sense, is a system in which political power is exercised primarily in the interest of the poor, regardless of the numerical or moral virtues of its citizens.

In contrast, a republic—or “polity,” as Aristotle terms it—is a mixed form of government in which citizens from all social classes participate, and laws are designed to serve the common good rather than the advantage of a particular group.

For the Romans, this distinction was particularly meaningful: the democratic principle, if applied in Rome, would resemble a “plebocracy,” where the plebeians held predominant influence, whereas the Res Publica ensured that both patricians and plebeians had rights and responsibilities, maintaining a balance between social classes for the benefit of the entire citizen body.

Within this framework, Republican Rome’s deep hostility toward monarchy can be understood as a reaction not only to political absolutism but also to its Dionysian dimensions. Monarchy in the Hellenistic world often carried sacral and ecstatic elements that clashed sharply with Roman ideals of restraint, civic order, and collective rule.

Mithridates VI of Pontus, one of Rome’s most formidable enemies, explicitly noted in his letter this Roman aversion to kingship in his correspondence, portraying Rome as ideologically opposed to monarchic power itself:

‘’ Once vagabonds with fatherland, with parents, created to be the scourge of the while world, no laws, human or divine, prevent them(the Romans) from seizing and destroying allies and friends, those near them and those afar off, weak or powerful, and from considering every government which does not serve them, especially monarchies, as their enemies.’’

Sallust, Histories 4.69.

Significantly, Mithridates styled himself Dionysus Eupator, a title that openly invoked the god associated with excess, liberation, and divine kingship. This self-identification was not incidental but reflected a broader Hellenistic tradition in which rulers claimed Dionysian attributes to legitimize their authority.

The Seleucid kings, also persistent adversaries of Rome, similarly aligned themselves with Dionysus, presenting their rule as both divine and transgressive of ordinary civic limits. To Republican Rome, such Dionysian monarchy represented everything it feared: the fusion of political power with religious ecstasy, personal charisma, and unchecked authority.

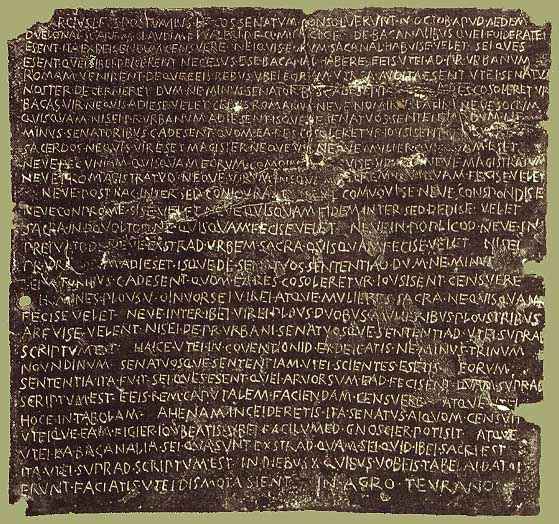

Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus

The Romans consistently perceived Dionysian mysticism as a direct threat to the moral and political foundations of their state and opposed it wherever it appeared. They regarded it as a subversive force imported from Greece and the Hellenistic East, capable of undermining Roman discipline, hierarchy, and civic virtue.

This fear helps explain the brutal suppression of the Bacchanalia in 186 BCE. According to Livy, the rites were introduced by a

“Greek of humble origin, versed in sacrifices and soothsaying,”

who transformed them into nocturnal gatherings marked by wine, ecstatic ritual, and communal feasting.

These secret ceremonies attracted large numbers of followers, both women and men, and spread rapidly beyond elite control. Particularly alarming to Roman authorities was the prominent role of women within the cult, which inverted Rome’s rigid patriarchal order and challenged traditional male authority.

Livy further claims that around seven thousand cult leaders and initiates were arrested in the aftermath of the scandal, and that most of them were executed. To the Roman mind, Dionysian worship fused religious frenzy with social disorder, dissolving boundaries between genders, classes, and moral norms. As a result, the Senate treated the Bacchanalia not as a harmless foreign cult but as a political and cultural threat that demanded ruthless repression.

The Political Causes of the Christian Persecution

Politically speaking, according to the philosopher Dimitris Liantinis, the Christians were persecuted precisely for the value system that they represented which stood in total contrast with that of Rome. While the Romans glorified might and military strength, Jesus would propose passive stance towards violence and anti-militarism(which was also the main reason that Marcus Aurelius committed persecutions).

Rome also glorified wealth and hard labour for slaves while Jesus would condemn the accumulation of wealth, favour distribution and propose that labour isn’t something important for God will take care of the believer through nature.

Also Rome glorified philosophy, science and knowledge while Christians glorified the common people and the less intelligent ones, furthermore Rome adhered to strict obedience to laws(Dura lex sed lex) while Jesus would forgive all people who committed crimes like thievery, robberies or prostitution but would condemn the strong ones, whether in wealth or intelligence.

At the same time, Jesus challenged the sacralization of imperial authority by declaring,

“Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s,”

Mark 12:17

thereby separating divinity from the emperor. Finally, he condemned both the hedonistic excesses of Roman life and, in certain teachings, relativized traditional family bonds—elements that, from a political perspective, were considered essential for procreation and demographic stability within the Roman state.

Moreover, in a society whose institutions—from the Senate to the provinces, local assemblies, and aristocracy—were grounded in political polytheism or at least henotheism, combined with patriotic loyalty to Rome, Christianity proposed a strict, personal, and universal rejection of worldly attachments. Christians proclaimed that the true fatherland lay in the Kingdom of Heaven and often discouraged active participation in military defense or civic cults tied to the state.

The Difference between Roman and Christian Values

Edward Gibbon, in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, examined the connection between Roman polytheism and its political institutions, arguing that the abandonment of pagan religion weakened social cohesion and made the empire more vulnerable to internal instability and external invasion.

Furthermore, the figure of Jesus himself could appear socially disruptive within the family-centered Roman culture. Born without a human father according to Christian belief, and teaching that spiritual kinship could surpass biological ties—as in Matthew 12:46–50, where he states that those who follow God’s will are his true family—Jesus relativized traditional familial structures.

In a society that regarded the patriarchal family as the foundation of legal, social, and political order, such teachings could easily be perceived as radical or even revolutionary. Furthermore Jesus believed in the equality of a free-man and a slave before God.

The connection between early Christianity and the Jewish communities of the first and second centuries cannot be overstated. In its formative period, Christianity emerged from within Judaism and remained closely intertwined with Jewish religious life and identity. During this same era, Rome fought three major Jewish wars and suppressed repeated Jewish revolts, often with extreme severity.

The Jews were regarded by many Roman authorities as a particularly suspect ethno-religious group, and Roman repression of Jewish uprisings reached some of its most violent expressions in Judea.

The Roman historian Tacitus reflects this perceived clash of value systems between Rome and both Jews and Christians. Notably, he does not clearly distinguish Christians from Jews, often treating them as part of the same religious category. In Histories 5.2–5, he writes:

“Among the Jews all things are profane that we hold sacred; on the other hand, they regard as permissible what seems to us immoral.”

He further adds:

"The other practices of the Jews are sinister and revolting… Proselytes to Jewry adopt the same practices, and the very first lesson they learn is to despise the gods, shed all feelings of patriotism, and consider parents, children, and brothers as readily expendable.”

He also remarks that

“their kings are not so flattered, the Roman emperors not so honored.”

The association of the Jewish and Christian God with Sabazios

Tacitus also notes that some writers perceived similarities between the worship of “Liber” (Dionysus) and the God of the Jews. At first glance, certain symbolic parallels between Jesus Christ and Dionysus appear striking. Both are associated with wine: Jesus transforms water into wine at Cana (John 2:1–11), and wine holds ritual significance within Jewish tradition as well (Psalm 104:15). Dionysus, too, was regarded as a savior figure (soter) in some traditions and was linked to themes of transformation, ecstasy, and renewal, even symbolic death and rebirth (as in the epithet Bromios).

Moreover, both Bacchic and Christian worship involve a ritual consumption of wine and a sacred element—meat in certain Dionysian rites and bread in Christianity—understood symbolically as participation in the divine presence.

Tacitus however notes that he sees a difference between the god Liber Pater and the god of the Jews:

"Their priests used to perform their chants to the flute and drums, crowned with ivy, and a golden vine was discovered in the Temple; and this has led some to think that the god thus worshipped was Liber, the conqueror of the East. But the two cults are very different. Liber founded a festive and happy cult: the Jewish belief is paradoxical and degraded.’’

Nonetheless the Romans would still associate the Jewish (and Christian) God with Sabazios, the ‘’barbaric’’ Dionysus. According to Valerius Maximus:

"Gnaeus Cornelius Hispalus, praetor peregrinus in the year of the consulate of Marcus Popilius Laenas and Lucius Calpurnius, ordered the astrologers by an edict to leave Rome and Italy within ten days, since by a fallacious interpretation of the stars they perturbed fickle and silly minds, thereby making profit out of their lies. The same praetor compelled the Judeans, who attempted to infect the Roman custom with the cult of Jupiter Sabazius, to return to their homes.’’

Strabo, in the first century BC, already connects Sabazios with Dionysus Zagreus, the son of Zeus and Persephone, who represents the chthonic or underworld manifestation of Dionysus. The followers of the cult of Sabazios were believed to maintain a close relationship with the spirits of Hades, and many of their rituals involved invocations intended to offer protection against evil spirits—what the Romans would call Lemures. The association between the Dionysian mysteries and magical or apotropaic practices is therefore particularly striking:

"The picture that Heraclitus sketches suggests at first glance a world in which holy men who characterized themselves as acolytes of Dionysus or as Iranian magoi offered initiation into mysteries that were suspect in the eyes of Heraclitus and no doubt of others.’’

Matthew W. Dickie, Magic and Magicians in the Greco-Roman World p. 26

"When the attendant who has been sent to arrest the ecstatic followers of Dionysus, the maenads and Dionysus himself, comes back with Dionysus in bonds but without the maenads, he also brings with him a report of the miracles (thaumata) that have attended the arrival of Dionysus in Thebes.’’

p. 73

Christianity and Magic

It was precisely this part of the Dionysian mysteries that the Romans opposed so much. They basically opposed the cult that would cause a man to abandon reason, to give himself up to his instincts and what they would regard as ‘’lower daemons’’ in exchange for powers. This for them was dangerous to humanity and most especially for human nature, which for most Romans was social and political while they would drive them to isolation. This was the precise accusation that Julian the Apostate gave against the Christians:

"Some men there are also who, though man is naturally a social and civilized being, seek out desert places instead of cities, since they have been given over to evil demons and are led by them into this hatred of their kind.

And many of them have even devised fetters and stocks to wear; to such a degree does the evil demon to whom they have of their own accord given themselves abet them in all ways, after they have rebelled against the everlasting and saving gods.’’

Julian the Apostate: Fragment of a letter to a priest

He also advises pagan priests to abstain from the Dionysian theaters of his time:

"No priest must anywhere be present at the licentious theatrical shows of the present day, nor introduce one into his own house; for that is altogether unfitting.

Indeed, if it were possible to banish such shows absolutely from the theatres so as to restore to Dionysus those theatres pure as of old, I should certainly have endeavoured with all my heart to bring this about; but as it is, since I thought that this is impossible, and that even if it should prove to be possible it would not on other accounts be expedient, I forebore entirely from this ambition.

But I do demand that priests should withdraw themselves from the licentiousness of the theatres and leave them to the crowd. Therefore, let no priest enter a theatre or have an actor or a chariot-driver for his friend; and let no dancer or mime even approach his door.

And as for the sacred games, I permit anyone who will to attend those only in which women are forbidden not only to compete but even to be spectators.’’

Rome wages war against the Christian ''superstition''

One of the most common accusations brought by the Romans against Christians was that of “superstition.” Suetonius refers to Christians as genus hominum superstitionis maleficae—“a class of men given to a malignant superstition.”

Pliny the Younger, in describing his investigations and prosecutions of Christians, explains that he felt compelled to examine whether the rapidly spreading movement posed any conspiratorial threat. As part of his inquiry, he ordered the torture of two female slaves who were called deaconesses. He concludes, however, that he found nothing beyond what he describes as a “depraved and excessive superstition” (superstitio).

The Greek term deisidaimonia (superstition) etymologically signifies fear of, or excessive reverence for, daemons. Thus, when Roman authorities accused Christians of superstition, the charge should not be understood in the modern sense of believing in something imaginary or irrational. Roman society was deeply religious and firmly believed in divine providence.

With the exception of certain philosophical schools—such as the Epicureans, and in different ways some Peripatetics—that questioned or rejected the existence of lower daemons and divine intervention, most Romans and Greeks accepted the reality of both benevolent and malevolent spiritual beings who exercised influence over human affairs.

It was therefore common to suspect that individuals who performed miracles or acts of sorcery—especially when such acts appeared to produce tangible benefits—were operating under the influence of malevolent daemons. Within this framework, labeling Christianity as superstitio implied not disbelief in its spiritual claims, but rather the conviction that its power derived from dangerous or impious spiritual forces.

The Neopythagorean Apollonius of Tyana—whose life was often compared by both Christians and pagans to that of Jesus—was likewise accused of practicing sorcery and of being under the influence of evil daemons. According to Philostratus, even the priests of the Eleusinian Mysteries were initially hesitant to initiate him, precisely because of suspicions surrounding his alleged magical practices.

Jesus the ''possessed'' magician

Accusations of involvement in magic were so widespread in antiquity that they became a recurring theme in pagan polemics against Christianity. Christian miracle-working, exorcisms, and prophetic claims were frequently interpreted not as signs of divine authority but as evidence of illicit magical arts.

In this context, the charge of sorcery functioned as a powerful tool for discrediting religious rivals within the broader spiritual and philosophical landscape of the Roman world.

Celsus would accuse Jesus of learning magic art for his miracles in Egypt:

"Hence, in consequence of being expelled by her husband, becoming an ignominious vagabond, she was secretly delivered of Jesus, who, through poverty being obliged to serve as a hireling in Egypt, learnt there certain arts for which the Egyptians are famous. Afterwards, returning from thence, he thought so highly of himself, on account of the possession of these [magical] arts, as to proclaim himself to be a God.’’

Arguments Of Celsus, Porphyry, And The Emperor Julian, Against The Christians, by Thomas Taylor p. 5

He even went as far as to claim that the miracles coming from incantations are in fact demonic and not real ones.

In the end Porphyry would not only claim that Jesus derives his miraculous powers from demons but that he himself is descended from evil spirits of the lowest order:

"There are terrene spirits of the lowest order, who in a certain terrene place are subject to the power of evil demons. From these were derived the wise men of the Hebrews, of whom Jesus also was one; as you have heard the divine oracles of Apollo above mentioned assert.

From these worst of demons therefore, and lesser spirits of the Hebrew, the oracles forbid the religious, and prohibit from paying attention to them, but exhort them rather to venerate the celestial gods, and still more the father of the gods.

But the unlearned and impious natures, to whom Fate has not granted truly to obtain gifts from the gods, and to have a knowledge of immortal Jupiter,—these not attending to the gods and divine men, reject indeed all the gods, and are so far from hating prohibited demons, that they even choose to reverence them.

But pretending that they worship God, they do not perform those things through which alone God is adored."

Augustin: De Civit. lib. xix. cap. 23

Taken together, the accusations of Celsus, Porphyry, and even Julian and other Roman writers reveal that the conflict between Rome and Christianity was not merely political, but also metaphysical.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: