The Continence of Scipio: A Legacy of Clemency in Roman History and Art

The story of how Scipio Africanus came to be a protagonist in numerous pieces of art, is the perfect how-to, in building a persona that lasts through the ages.

Renaissance and Baroque painters, found in Livy’s account, a dramatic and moralistic tableau, where virtue triumphed over personal gain or passion. By placing this moment on canvas, artists immortalized Scipio’s humanity and set it against the backdrop of grandeur and restraint, echoing themes central to both Roman ideals and the cultural rebirth of the classical world in Europe.

From Roman General to Idealized Icon in Literature and Art

The idealization and demilitarization of Scipio Africanus in literature and art can be traced back to the Renaissance, particularly to Petrarch, who exalted Scipio as the epitome of Roman virtue. In his epic Africa and other works, Petrarch presented Scipio as a Christ-like figure who conquered through moral superiority rather than violence.

This narrative contrasted sharply with historical accounts, which included Scipio's role in the brutal siege of New Carthage. Petrarch’s focus on virtue over military exploits shaped later portrayals, emphasizing Scipio's clemency and chastity while downplaying the harsher realities of his campaigns.

Machiavelli later adopted this idealized image of Scipio but infused it with skepticism in The Prince and his Discourses on the First Decade of Livy. While acknowledging Scipio’s strategic use of kindness as a political tool, Machiavelli suggested that appearances of virtue often masked pragmatic motivations, thus complicating the narrative of Scipio as a purely moral figure.

Despite these nuances, Machiavelli avoided directly confronting Scipio's more ruthless actions, such as the massacre at New Carthage.

A gravure of the Massacre of Carthage. Credits: Rijksmuseum, Public domain

Erasmus, a radical pacifist, popularized Scipio as a model of princely virtue in works like The Education of a Christian Prince. Using Scipio as an example, Erasmus emphasized clemency, chastity, and the moral responsibilities of rulers, advocating for depictions of leaders engaged in virtuous statecraft over indulgence or tyranny. His writings, widely circulated in the Netherlands, influenced 17th-century Dutch art, where Scipio became a favored subject for public and private commissions.

These cultural reinterpretations transformed Scipio into an enduring emblem of leadership and virtue, overshadowing his military achievements. His story, particularly the Continence of Scipio, resonated across Europe as an idealized narrative of moral restraint, inspiring countless works of art and literature that celebrated his character while selectively overlooking the complexities of his historical reality. (From Criminal to Courtier: The Soldier in Netherlandish Art 1550-1672, by David Kunzle)

The Divine Command of Scipio Africanus: Livy’s Account of a Roman Hero

According to Livy in his Ab Urbe Condita, the Roman Republic’s fortunes during the Hannibalic War began to shift in late 211 BCE when the young Publius Cornelius Scipio was elected as privatus cum imperio pro consule and sent to Spain. This marked the start of a decisive phase in the conflict, ultimately leading to Rome's triumph over its greatest adversary.

Livy presents Scipio as a figure of almost mythical stature, attributing his rise not only to his extraordinary abilities but also to his calculated cultivation of a divine image. From a young age, Scipio visited the Capitol daily, conducting his public and private affairs under the perceived guidance of the gods.

Livy recounts how Scipio’s deliberate embrace of religious symbolism and association with divine ancestry inspired public confidence in his leadership, even at a time when he had yet to hold a major magistracy. He contrasts Scipio’s genuine talents with his clever manipulation of public perception, weaving a narrative that questions whether his divine aura stemmed from authentic piety or a calculated strategy.

Echoing tales of Alexander the Great, Scipio allowed rumors of his divine origins to flourish without confirmation or denial. This enigmatic blend of real and crafted qualities, Livy argues, explains how the Roman people entrusted a young man with the monumental responsibility of defeating Hannibal and reclaiming Rome's dominance.

The Ambiguities of Leadership

Livy’s portrayal of Scipio Africanus stands apart from Polybius’ detailed and rational depiction, offering a dramatic and ideologically layered narrative that reshapes the legendary Roman leader’s image. While Polybius celebrates Scipio’s rationality and military brilliance, rejecting divine myths as distortions, Livy emphasizes Scipio’s calculated use of such myths to inspire trust and gain public support, particularly during his unprecedented appointment as proconsul at the young age of 24.

Livy situates Scipio’s portrait within the broader context of the Second Punic War, intertwining his virtues with the popular belief in his divine connection. Unlike Polybius, who meticulously lists Scipio’s intellectual and strategic traits, Livy focuses on the leader’s ability to manipulate perceptions, leaving ambiguous whether Scipio himself believed in these divine rumors or merely exploited them.

This portrayal adds complexity to Scipio’s character, contrasting with the uncritical admiration of earlier sources.

A gravure from a bust of Scipio Africanus. Credits: Peter Paul Rubens, Rijksmuseum, Public domain

Further, Livy’s treatment suggests deliberate independence from Polybius’ narrative, blending dramatic flair with a subtle critique of Scipio’s leadership. Though some of this ambiguity might derive from annalistic traditions like those of Valerius Antias, Livy’s nuanced storytelling transforms Scipio from a mere military hero into a multifaceted figure whose leadership thrived on both genuine skill and astute manipulation of public belief.

Virtues, Ambiguities, and the Power of Perception

Polybius emphasizes Scipio’s rationality and strategic brilliance, dismissing myths of divine intervention as fabrications. In contrast, Livy delves deeply into Scipio’s ability to manipulate public perception, blending real virtues with carefully staged displays of divine favor.

Livy highlights Scipio’s calculated use of religious imagery, nocturnal visions, and rumors of a divine ancestry to win the unwavering support of the Roman people, even as these strategies skirt the boundaries of Roman moral and religious traditions. The portrait reveals Scipio’s mastery of ars, a term Livy associates with military stratagems but also with a troubling connotation of deception.

This calculated approach—rooted in ostentation and an exploitation of superstitio—positions Scipio as a leader who transcends conventional Roman virtues. However, Livy’s narrative suggests unease, framing these traits as both necessary for victory and potentially subversive to the ideals of the mos maiorum.

Livy further complicates the portrayal by comparing Scipio to Alexander the Great, another figure renowned for blending heroism with personal ambition. While the comparison elevates Scipio’s status, it also casts a shadow, as Livy’s previous critique of Alexander’s monarchical excesses and disdain for Republican values lingers in the background.

This parallel highlights Scipio’s divergence from traditional Roman heroism and suggests an undercurrent of criticism toward his Hellenistic style of leadership.

A painting of Nicolas Andre Monsiau of Alexander the Great Attacking the Oxydrakai. Public domain

In the climactic section of the portrait, Livy comments on how Scipio’s ars and calculated displays fostered admiration that exceeded human limits, implying a dangerous imbalance in the public’s perception of him. By focusing on Scipio’s duplicitous yet effective strategies rather than solely on his virtues, Livy invites readers to grapple with the moral complexities of power, charisma, and the use of public belief as a political tool.

Ultimately, Livy does not deny Scipio’s greatness or his vital role in Rome’s survival during the Second Punic War. However, he presents a leader whose success relied as much on his ability to manipulate appearances as on his genuine talents.

This layered depiction of Scipio Africanus offers a thought-provoking exploration of the tensions between virtue, ambition, and the practical demands of leadership in times of crisis. It underscores Livy’s enduring relevance as a historian who challenges readers to reflect on the moral intricacies of power and governance. (Livy on Scipio Africanus. The commander's portrait, by Luca bertramini & Marco Rocco, Universita di Padova)

The Continence of Scipio: A Classical Virtue Transformed into Renaissance and Baroque Art

The story of The Continence of Scipio encapsulates the moral ideals of restraint, generosity, and justice through a vivid episode from the life of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. This legendary narrative, rooted in classical sources such as Polybius and Livy, recounts Scipio’s noble treatment of a captured Celtiberian girl during the Roman conquest of New Carthage in 209 BCE.

As a young commander in Spain, Scipio's surprise capture of the city provided Rome with strategic advantages, a wealth of resources, and numerous prisoners. Among the spoils was a beautiful Celtiberian girl, presented to Scipio as a gift by his soldiers, who admired his reputed fondness for women.

Despite his astonishment at her beauty, Scipio displayed remarkable self-restraint. In Polybius’ account, he returned the girl to her father unharmed, illustrating his famed continence. Livy’s retelling expands the story, introducing a romantic subplot involving the girl’s fiancé, Aluccius, a Spanish prince.

Scipio not only reunited the lovers but also gave their family ransom money as a wedding gift, securing their loyalty to Rome. Aluccius, overwhelmed by Scipio's magnanimity, pledged his support and returned with 1,400 cavalrymen, furthering Scipio's military efforts.

Dutch Baroque and Civic Significance

Dutch art theorists, such as Karel van Mander and Samuel van Hoogstraten, emphasized Scipio's continence as an ideal subject for history paintings, blending moral instruction with artistic grandeur. Van Mander admired Scipio’s self-control, aligning it with biblical wisdom from Proverbs 16:32, which extols ruling one's spirit over conquering a city.

These virtues resonated with the values of the Dutch Republic, making Scipio a popular symbol in public buildings and town halls. Artists like Jan Lievens and Gerard de Lairesse frequently depicted Scipio’s story in civic spaces to inspire leaders with his virtues of restraint and justice.

Art and Adaptation

Scipio’s continence inspired numerous artists, including Rembrandt’s pupil Govert Flinck and the Baroque painter Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, whose The Continence of Scipio (Philadelphia Museum of Art) is a masterpiece of narrative art.

The painting captures the story’s dramatic climax: Scipio, flanked by Roman advisors and soldiers, stands on a low staircase, while the young couple kneels before him in gratitude. The girl’s family, accompanied by servants, presents the ransom, which Scipio generously returns. The background depicts the bustling aftermath of the conquest, with spoils and captives in transit and the fortified cityscape of New Carthage looming behind.

Van den Eeckhout’s interpretation reflects his training under Rembrandt, employing chiaroscuro and vibrant color to enhance the emotional intensity. His design incorporates the classical adlocutio format, inspired by Roman reliefs and Renaissance adaptations, emphasizing Scipio’s role as a magnanimous leader. The artist’s inclusion of elaborate still-life details, such as gold and silver vessels, underscores his background as the son of a goldsmith.

The enduring appeal of The Continence of Scipio lies in its universal themes of virtue and leadership. From Renaissance Italy to the Dutch Republic, Scipio’s story transcended its historical context to become a moral allegory celebrated in paintings, plays, and political discourse. Whether displayed in civic halls to inspire governance or commissioned by private collectors to embody noble ideals, the narrative continues to resonate as a testament to the timeless value of restraint, justice, and the moral authority of virtuous leadership. (The Continence of Scipio by Gerbrandt van den Eeckhout, by Peter C. Sutton, Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin)

Van Dyck’s Continence of Scipio: A Masterpiece of Theatrical Symbolism and Moral Allegory

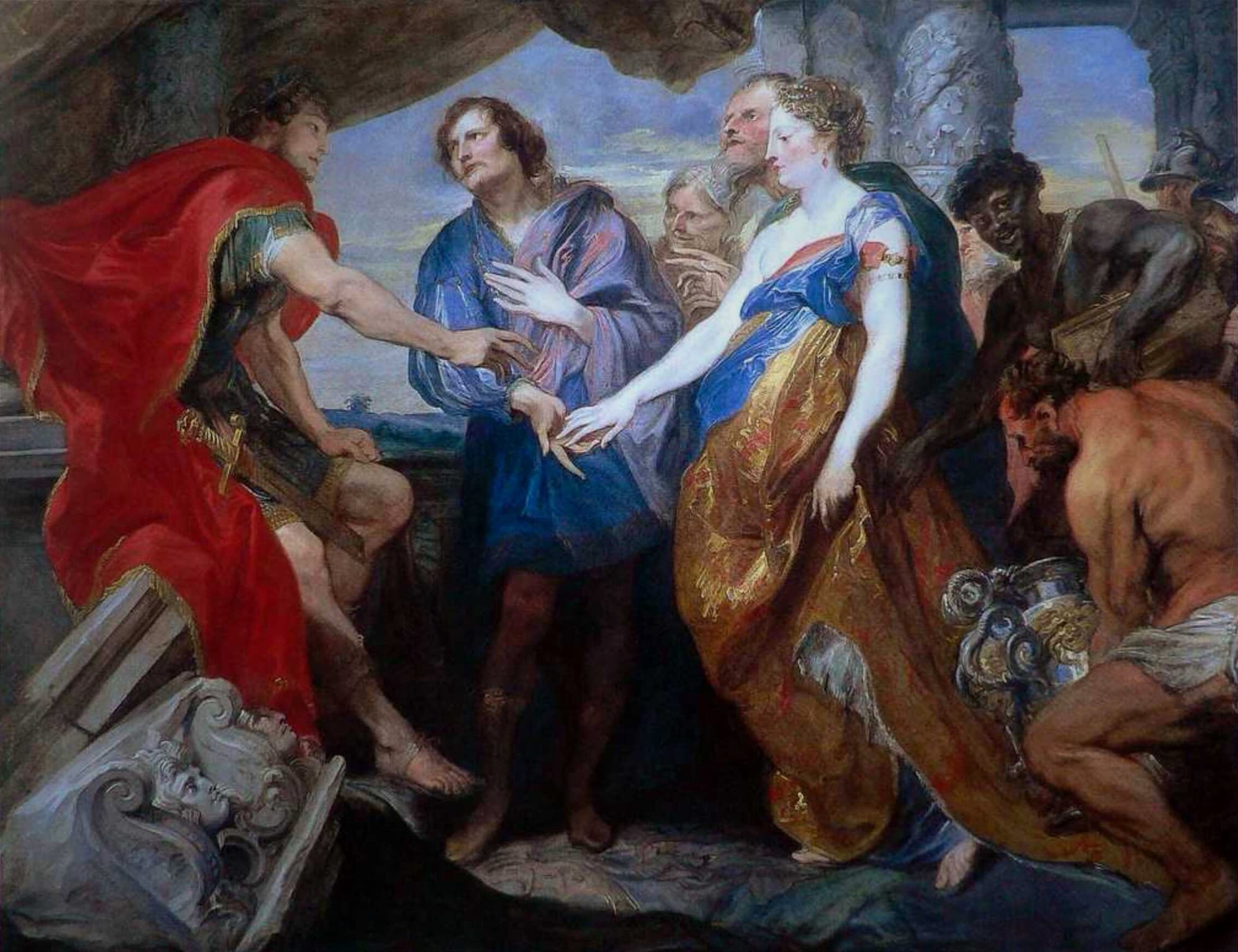

Van Dyck’s The Continence of Scipio stands as a remarkable synthesis of historical narrative, symbolic depth, and theatrical artistry. Painted during Van Dyck’s first stay in England in 1620–1621, it was commissioned by George Villiers, the powerful Marquis of Buckingham and favorite of King James I.

In this vibrant work, Van Dyck blends emblematic and mythological elements with the historical episode of Scipio Africanus’ famed act of restraint, creating a painting deeply informed by the cultural tastes and politics of the Jacobean court.NVan Dyck’s interpretation of the moment is layered with Jacobean cultural and personal symbolism.

Art historian Jeremy Wood has argued that the figures of Aluccius and his fiancée are likely portraits of Buckingham and his wife, Lady Katherine Manners. This personalization adds a topical resonance to the theme of chastity, reflecting the public scrutiny of the couple’s premarital relationship. The inclusion of an elephant motif on the carpet beneath the couple—a symbol of temperance and chastity—further underscores this connection.

Van Dyck’s composition extends beyond the immediate narrative to incorporate emblematic and mythological elements that enrich its thematic scope. Scipio’s magnanimity is mirrored by Aluccius’ gratitude, expressed in both his gaze and posture. Livy’s description of Aluccius being "overwhelmed by a mixture of joy and shame" is vividly realized in the character’s blush and his multi-colored cloak, which seems to embody his shifting emotions.

The young woman, on the other hand, stands as a symbol of modesty, her downcast eyes and exposed shoulders contrasting with the proud composure of her fiancé. The inclusion of a fragment of an antique frieze at Scipio’s feet, likely sourced from Buckingham’s collection, adds historical authenticity while introducing another layer of meaning. The frieze, adorned with gorgon heads, evokes the mythological dangers of looking and acts as a visual anchor for the painting’s intricate interplay of gazes.

Scipio looks directly at Aluccius as he gestures over the couple’s hands, symbolizing their union, while the gorgon heads below engage in their own parody of the scene, reinforcing the theme of vision and its moral implications. Van Dyck draws on the theatrical traditions beloved by the Jacobean court to amplify the painting’s dramatic impact.

The figures are arranged on a narrow, stage-like foreground, an arrangement reminiscent of Veronese and other Venetian masters whose works were well-represented in Buckingham’s collection. The composition’s frieze-like quality is further emphasized by the interplay between human figures and inanimate objects, such as the heavy vase in the foreground, which echoes the woman’s form and physical presence.

Van Dyck also borrows from the animistic traditions of Rubens, with whom he apprenticed. In The Continence of Scipio, objects such as the frieze and vase are imbued with an almost sentient quality, contributing to the painting’s rich emotional and narrative tapestry. The elephant in the carpet, glaring comically, contrasts the earnest expressions of the human subjects, adding a playful undertone to the scene’s moral gravity.

A Moral and Political Allegory

The painting not only celebrates Scipio’s legendary virtue but also serves as a moral allegory aligned with Buckingham’s personal and political aspirations. Scipio’s restraint and generosity are paralleled with Buckingham’s cultivated image as a virtuous and magnanimous leader.

The symbolic elements—the elephant, the antique frieze, and the gorgon heads—all converge to create a visual language that bridges the ancient and the contemporary, reflecting the ideals of temperance and magnanimity held in high regard by the Jacobean elite. (Looking at Van Dyck’s Scipio in its contexts, by John Peacock)

A Roman Hero in a Hellenistic Lens

Scipio Africanus, a towering figure of the Roman Republic, is best remembered for his pivotal role in the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) and his legendary defeat of Hannibal at Zama. While his military achievements have been extensively analyzed, the cultural dimensions of his public persona have received far less attention.

Scipio’s public persona was not merely a product of Roman traditions but was deeply influenced by Hellenistic practices. Emerging during a period of intense cultural interaction across the Mediterranean, Scipio adopted and adapted the self-promotional techniques of Hellenistic rulers. This approach challenges the traditional view that the so-called “Scipionic Legend”—a collection of myths, omens, and rumors surrounding his life—was largely fabricated by later authors.

Instead, Scipio appears as an active agent in crafting his legacy, deliberately drawing on Hellenistic motifs to elevate his status.

A possible representation of Scipio Africanus using a Greek example during one of his speeches. Illustration: Midjourney

By positioning himself as a Hellenistic-style leader, Scipio cultivated an image that resonated with the broader Mediterranean world while simultaneously appealing to Roman values. His behavior, including the use of omens, public rituals, and grand gestures, mirrored the self-presentation of figures like Alexander the Great and the Diadochi.

These elements of his persona were not mere fabrications but strategic choices that aligned with a broader trend of Hellenization among Rome’s elite in the 3rd and early 2nd centuries BC. Scipio here, is placed within the context of his contemporaries and predecessors, revealing that his methods were an evolution of existing promotional trends rather than an unprecedented innovation. It also underscores how his image reflected the cultural and political atmosphere of Rome during its early expansion into the eastern Mediterranean.

By examining Scipio through a Hellenistic lens, this analysis offers new insights into his identity, leadership, and the cultural dynamics of his time, challenging traditional narratives of his legacy and reaffirming his role as a transformative figure in Roman and Mediterranean history. Scipio Africanus is celebrated as a key figure of the Roman Republic and a military genius during the Second Punic War, and is often analyzed for his tactical brilliance and victories.

However, his image and self-presentation reveal a deeper, culturally complex persona influenced by the Hellenistic traditions of his era. This analysis highlights Scipio as an innovator who strategically utilized Hellenistic methods of self-promotion to craft a legacy that resonated with both Roman and Mediterranean audiences.

Scipio’s alignment with Hellenistic ideals is evident in his adoption of personal imagery, public rituals, and narratives that mirrored the divine associations of figures like Alexander the Great. These strategies were not fabrications of later writers but deliberate choices by Scipio to elevate his status and influence. His public persona, shaped by both Roman traditions and Hellenistic culture, reflects a transitional period in Roman society as it absorbed and reinterpreted Mediterranean influences.

Modern scholarship often debates whether Scipio’s Hellenistic attributes were authentic or retrospective constructions. While traditional analyses have focused primarily on his military achievements, this perspective argues that his self-presentation as a Hellenistic-style leader was a conscious and innovative response to the cultural dynamics of his time.

By framing Scipio within a broader Mediterranean context, this study sheds new light on his leadership, legacy, and the intricate interplay between Roman and Hellenistic worlds during the Punic Wars. (The Presentation of Scipio Africanus: Hellenization and Roman Elite Display in the 3rd and 2nd Centuries BC, by Sarah Prince, The University of Queensland, Australia)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: