Shaping a Legend: The Evolution of Trajan’s Reputation

Emperor Trajan, is remembered by history as one of Rome’s greatest leaders, who epitomized the ideals of a just and capable ruler.

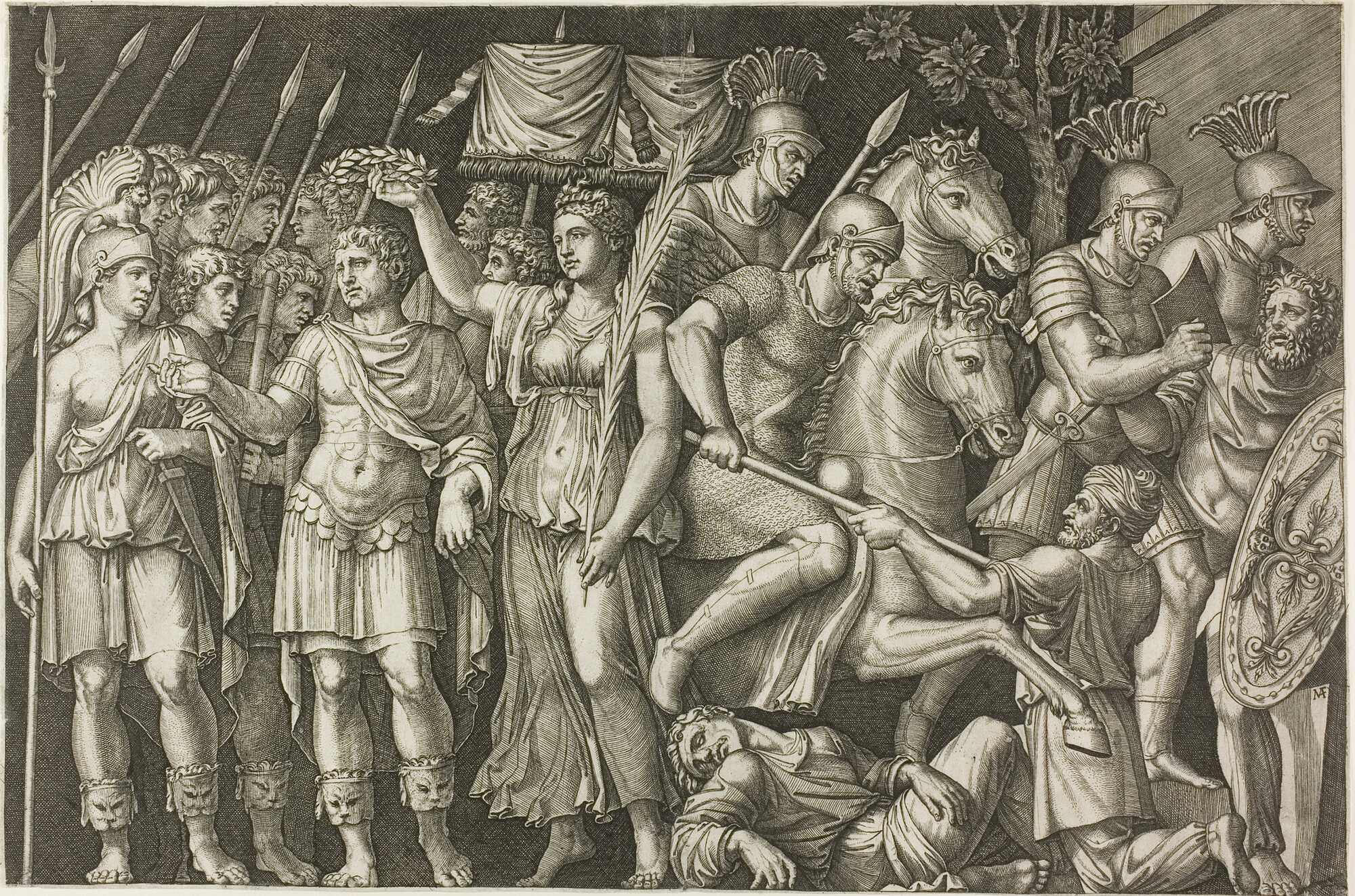

Ascending to power in 98 CE, Trajan ushered in a period of unprecedented prosperity and expansion, marked by his military triumphs, most notably the conquest of Dacia, and his ambitious civic projects, including the awe-inspiring Trajan’s Column.

Renowned for his fairness and humility, he earned the title optimus princeps—the best ruler—reflecting the profound respect he commanded both during his reign and in the records of history. His legacy extends beyond his battlefield victories and monumental achievements; it lies in the vision of an emperor who balanced strength with compassion, leaving an indelible mark on the Roman Empire.

The Making of a Model Emperor

In his panegyric for Honorius’ fourth consulship (398 CE), the poet Claudian prominently positioned him as a role model for the young emperor. This notion is introduced early in the poem:

“Not unworthy of reverence nor only just acquainted with war is the family of Trajan and that Spanish house which has showered diadems upon the world.”

The theme reaches its peak in an imagined speech by Theodosius advising his son Honorius:

“The fame of Trajan will never die, not so much because thanks to his victories on the Tigris conquered Parthia became a Roman province, not because he broke the might of Dacia and let their chiefs in triumph up the slope of the Capitol, but because he was kindly to his country.

Fail not to make someone like him your example, my son.”

Trajan’s reputation as a model emperor is encapsulated in Eutropius’ famed phrase:

“More fortunate than Augustus, better than Trajan.”

Eutropius elaborates further, noting,

“To such an extent has the reputation of his goodness lasted that it provides those who either (wish to) flatter or to praise him sincerely with the opportunity to use him as the most outstanding model.”

It was common for authors like Claudian and Eutropius to compare contemporary rulers to past emperors, as Roman society valued exemplarity highly. Certain emperors became benchmarks for ideal conduct, against which future rulers were evaluated; always bearing in mind to avoid the worst examples. By the fourth century, he had firmly joined this elite group of model leaders.

However, modern scholarship often assumes that Trajan’s virtues were already the standard for evaluating second- and third-century emperors.

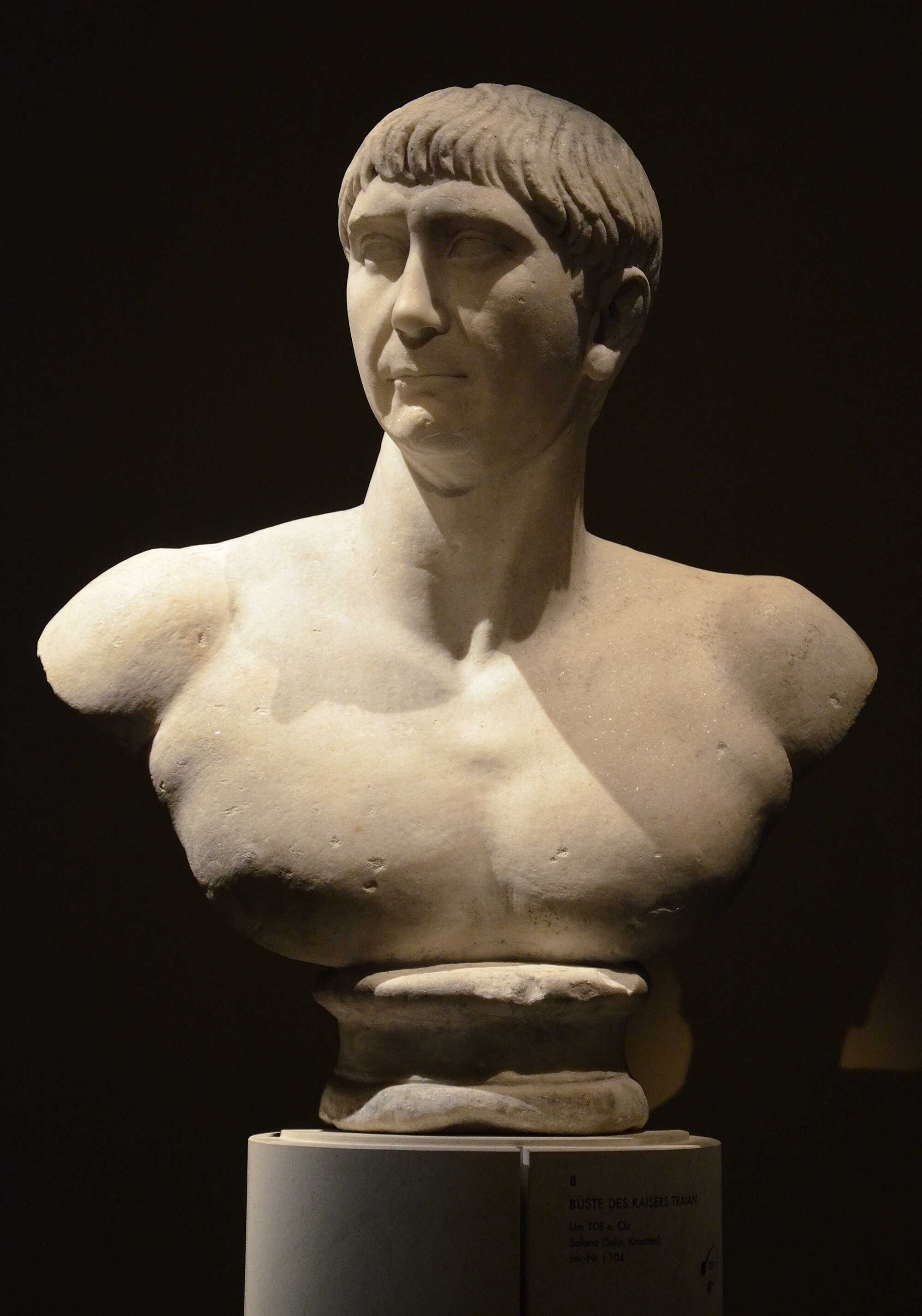

Bronze statue of Roman Emperor Trajan. Credits: Crisfotolux from Getty Images, by Canva

This view is challenged here, suggesting instead that his elevation as a model ruler was a late-antique literary construct. His status evolved over time, reaching prominence in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. This development was influenced by the ideological needs of the late fourth century and the availability of historical materials on Trajan.

This argument is supported by tracing references to him in both literary and material sources. Explicit literary references, such as panegyrics and histories, attempted to solidify his image as a model emperor, though this was only fully realized in the fourth century.

Material sources, such as inscriptions, coins, portraits, and monuments, offer more implicit evidence of his legacy. These, too, indicate that his inclusion among exemplary leaders became significant during Constantine’s reign and was further solidified under Theodosius.

Trajan’s enduring reputation as an exemplary ruler was thus not an immediate phenomenon but a constructed legacy, shaped by the changing needs and ideologies of later Roman society.

The Evolution of Trajan’s Reputation

The concept of Trajan as a role model for future emperors was introduced during his lifetime. Pliny the Younger, in his Panegyricus to Trajan on September 1, 100 C.E., made this explicit:

“Good rulers to recognize what they have done and bad ones learn what they ought to do.”

In one of his letters, Pliny further remarked that his goal was:

“to encourage our emperor in his virtues through sincere praise,”

while also:

“to advise future emperors by means of example.”

Despite Pliny’s efforts, Trajan’s image as an exemplary ruler did not take immediate hold. In the century following his death, historiographical accounts offered mixed evaluations of his reign. For example, Fronto, (Roman orator, rhetorician, and statesman of the 2nd century CE, who lived during the reigns of emperors Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius) writing around 165 C.E., noted that:

“[his] own glory was likely to have been more important to him than the blood of his soldiers”

and added that, in terms of justice and clemency:

“Trajan was not equally cleared in the eyes of all.”

Similarly, Tacitus, Cassius Dio, and Herodian offered ambivalent depictions.

Tacitus implied criticism of Trajan’s rule, and Herodian barely mentioned him, favoring Augustus and Marcus Aurelius as positive exemplars. Dio acknowledged his generosity and respect for the elite, but also highlighted his affinity for wine and boys.

It was only fter the fourth century, as a new senatorial elite emerged, that Pliny’s praise of Trajan gained renewed appreciation. Explicit mentions of him appeared in speeches such as Themistius’s 364 C.E. address to Jovian, where he highlighted Trajan’s promotion of philosophy:

“The great Trajan, Dio the Golden-Tongued... By adopting philosophy in the sight of all, you [Jovian] follow in these men’s footsteps.”

Similarly, Ausonius in 379 C.E. and Pacatus in 389 C.E. invoked his civil and military achievements in comparison to Julian, Gratian, and Theodosius.

By the late fourth and early fifth centuries, his reputation solidified, particularly in military contexts. Claudian urged Honorius to emulate Trajan’s victories over the Parthians and Dacians. Sidonius Apollinaris, in praising Avitus, depicted the goddess Roma lamenting her fallen glory, stating:

“I know not if anyone can match Trajan – unless perchance you, Gaul, should once more send forth a man who should even surpass him.”

Ultimately, the trajectory of his legacy was gradual. Initially one among many exemplary rulers, he only emerged as the model emperor in the late fourth and early fifth centuries.

This nuanced evolution highlights how historical contexts and literary traditions shaped the perception of Trajan’s idealized emperorship. Material evidence, such as coins and monuments, aligns with this late development, further reinforcing his stature as an exemplary ruler of antiquity. (The Fame of Trajan: A Late Antique Invention, by Olivier Hekster, Sven Betjes, Sam Heijnen, Ketty Iannantuono, Dennis Jussen, Erika Manders, Daniel Syrbe)

From Roman Justice to Medieval Legend

In “Trajan Optimus Princeps: A Life and Times”, Julian Bennett explores the enduring legacy of Emperor Trajan, whose reputation has transcended centuries. During his lifetime, he was affectionately known as Optimus Princeps, or the "perfect prince." After his death, his popularity endured, with later generations deeming no other emperor his equal.

Bennett highlights that, by the mid-fourth century, Trajan was celebrated for his "utmost integrity and virtue in affairs of state" and "total fortitude in matters of arms." She also notes that the Roman Senate reportedly greeted each new emperor with the hope that they might "surpass the felicity of Augustus and the excellence of Trajan."

His architectural achievements further solidified his legacy. Emperor Constantius II, visiting Trajan’s Forum in Rome, remarked it was:

“the most exquisite structure under the canopy of heaven, admired even by the gods themselves.”

Centuries later, Cassiodorus echoed this admiration, writing:

“The Forum of Trajan, no matter how often we see it, is always wonderful.”

The Middle Ages embraced his memory with fervent affection, weaving his legacy into both history and legend. A twelfth-century chronicler praised him for his contributions to public works, likening his deeds to acts of sanctity, much like the construction of charitable structures by Muslims.

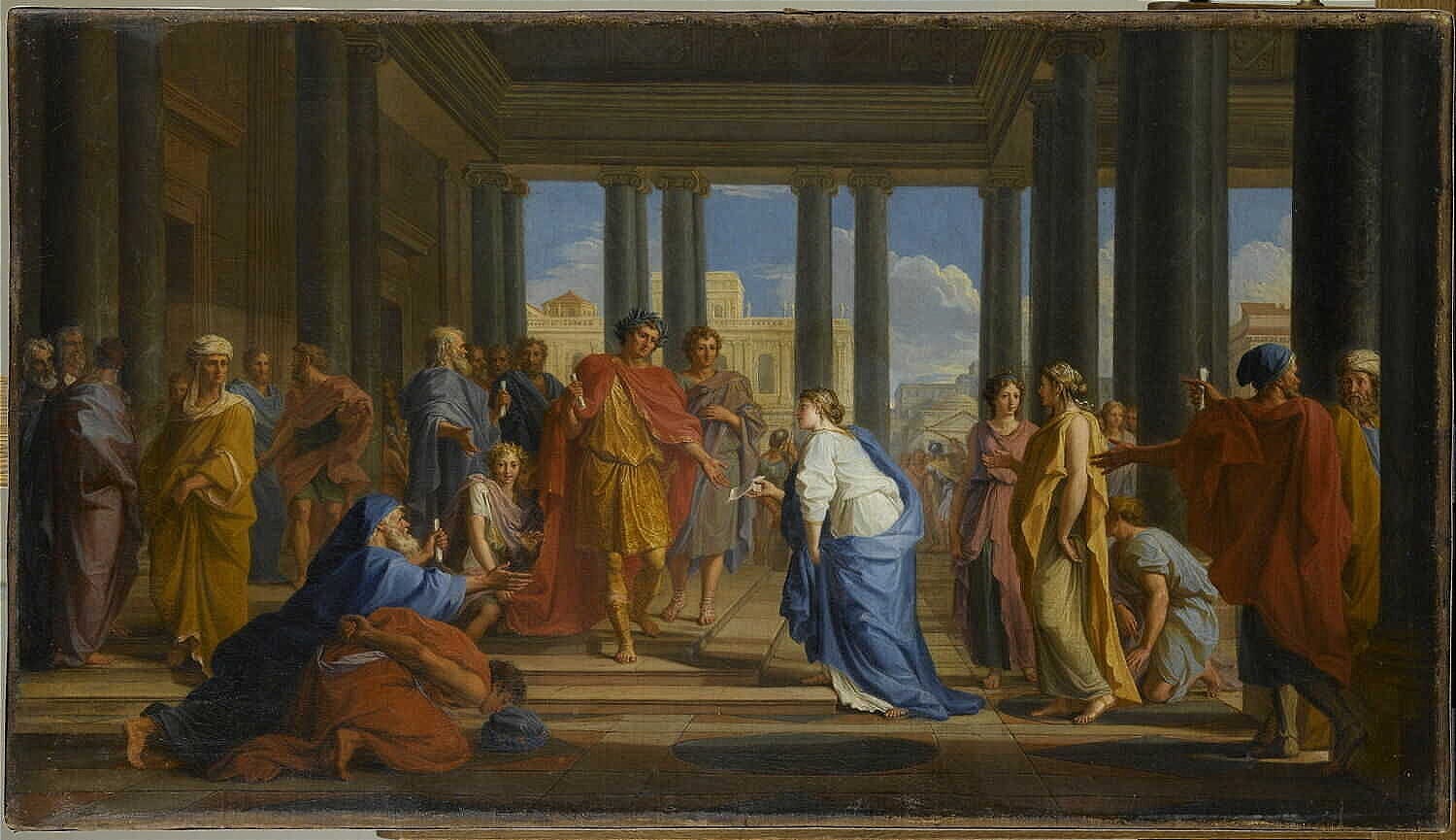

This admiration birthed a widely recounted medieval tale of Trajan’s justice. According to the story, Pope Gregory the Great heard of an incident in which Trajan, poised to march with his army, paused to ensure justice for a grieving widow who demanded retribution for her son’s murder.

When she questioned whether another’s actions could redeem his failure to act, Trajan dismounted and declared:

"Justice calls me, pity binds me here."

Moved by this tale, Gregory prayed for his salvation, reportedly prompting God to pardon the emperor—a rare act for a pagan.

A possible representation of Pope Gregory the Great, praying for the salvation of Trajan’s soul. Illustration: Midjourney

This account, though controversial for its theological implications, inspired art, literature, and moral discourse throughout the Middle Ages. Dante placed Trajan among the Just and Temperate Rulers in Heaven in his Divine Comedy, noting that his redemption must have been predestined by God.

The legend became a popular subject in art, appearing in works like Jacopo Avanzi’s altar piece, which depicts Gregory’s intercession, and Michael Pacher’s triptych, which shows Trajan emerging from Hell in response to Gregory’s prayers.

Trajan’s legacy persisted into the Enlightenment and beyond. Edward Gibbon described his reign as the start of Rome’s Golden Age, and his memory inspired operas and monumental art. In the 1930s, Italian sculptors chose him to represent justice in a bas-relief for the U.S. Supreme Court.

While some aspects of his legend, such as the story recounted to Gregory, may trace their origins to Hadrian or be derived from Trajan’s monuments, what endures is the admiration and respect Trajan inspired, which Bennett’s work seeks to unravel.

The Roots of Optimus Princeps

The historian Cassius Dio, himself of provincial origin, expressed skepticism about Emperor Trajan's heritage, noting with disdain that he was:

"an Iberian, and neither an Italian nor even an Italiot."

However, historical evidence suggests that Trajan’s paternal family, the gens Ulpia, likely originated from Tuder (modern Todi) in Umbria. His formal name, Marcus Ulpius Traianus, supports this connection, as both his gentilicium, Ulpius, derived from the Latin lupus (wolf), and his cognomen, Traianus, were linked to names and linguistic traditions of the Osco-Umbrian region.

Despite this potential Italian origin, the gens Ulpia was not particularly distinguished in Rome. His father, also named Traianus, was the first in the family to achieve consular rank, likely due to imperial favor rather than senatorial election.

By the time of his birth, the family had settled in Italica (modern Santiponce) in southern Spain, a prosperous town founded by Scipio Africanus in 206 BCE. Italica, strategically located near fertile plains and the River Baetis, thrived as a hub for agriculture and trade, becoming a key part of Rome’s lucrative Baetican olive oil industry.

Baetica’s wealth was evident by the late first century CE, with extensive municipal and private building projects, including the expansion of Italica. The town’s new district, developed during Trajan’s youth, reflected its importance as a center of commerce and culture.

Italica’s agricultural success, particularly in olive oil production, was instrumental in the region’s prosperity. Baetican olive oil was highly valued, transported across the empire in distinctive amphorae, and heavily exported to Rome, where discarded amphorae eventually formed the Monte Testaccio.

Trajan’s rise was rooted in these advantageous circumstances. His family's wealth, possibly accrued through the olive oil trade and strategic marriages, provided the means for social advancement. By the late first century BCE, Italica's elevation to municipal status under Augustus further enabled families like the Ulpii to enter the equestrian and senatorial orders. His own father’s ascent to the senatorial rank likely reflected this social mobility, marking the beginning of the family’s rise to prominence in Rome.

Trajan’s provincial heritage and the wealth of Baetica highlight the interconnectedness of Rome’s provinces with its imperial power. His lineage, though initially viewed as unremarkable, laid the foundation for a ruler who would become celebrated as Optimus Princeps, embodying Rome’s ideals and accomplishments.

The Making of Optimus Princeps

The early life and career of Emperor Trajan, before his historical emergence in 89 CE, are pieced together from limited sources and anecdotes. Raised in a noble family, he likely received a traditional Roman education, heavily influenced by Quintilian’s rhetoric and the classics. Though not known for exceptional academic brilliance, he demonstrated a functional command of Greek and composed lucid correspondence, such as the letters to Pliny the Younger, which reflect Caesar-like terseness.

His military career began with his appointment as tribunus laticlavius at a young age, likely serving in legions stationed in Syria under his father’s governance and later on the Rhine. His lengthy service, unusually spanning multiple postings, provided him with critical military and administrative experience. Pliny's Panegyricus praised Trajan's dedication and adaptability, though some claims, like his "ten years of service," appear rhetorical rather than factual.

In 86 CE, Trajan became praetor, marking his entry into higher public service.

A possible representation of Trajan walking the streets of Ancient Rome as a praetor. Illustration: Midjourney

Unlike most patricians, he accepted a legionary command of Legio VII Gemina in Spain, a post far from major conflicts. This command, though modest, positioned him for crucial roles during Domitian’s reign, including aiding the emperor during Saturninus’ rebellion. Trajan's loyalty and competence set him on a trajectory that ultimately culminated in his adoption by Nerva and succession to the imperial throne.

Trajan’s rise illustrates the interplay of personal ambition, strategic appointments, and fortuitous circumstances, paving the way for his eventual acclaim as Optimus Princeps. His early life and service, though marked by routine senatorial duties and military postings, were pivotal in shaping his leadership and securing his legacy.

The Ethics of Power: Pliny’s Eulogy of Trajan

Pliny’s Panegyricus, a significant piece of imperial rhetoric, exemplifies the art of praising Trajan through paradoxical antitheses that highlight his exceptional character. As Pliny proclaims early in the speech:

“Nowhere should we flatter him as a divinity and a god; we are talking of a fellow-citizen, not a tyrant, one who is our father, not our over-lord”.

This balance of divine-like qualities and human accessibility defines Trajan’s unique portrayal in Roman panegyric. Pliny employs stylistic techniques, such as juxtaposing opposites, to emphasize Trajan's paradoxical virtues: his securitas (confidence) contrasts with pudor (modesty), his role as commilito (comrade-in-arms) balances with his authority as imperator (commander), and his status as princeps (emperor) juxtaposes with his humility as privatus (citizen).

For instance, Pliny marvels at how Trajan combined the responsibilities of an emperor with the modesty of a private citizen:

“You are princeps with the discernment of a privatus”.

Trajan’s divine qualities are subtly incorporated without overstating them, a deliberate effort by Pliny to avoid the hubris associated with predecessors like Domitian. He is often likened to a “swift-moving star” who intervenes in human affairs with divine efficiency, but Pliny avoids outright deification, highlighting his humility and his refusal to seek divine honors.

Eventually, Trajan is described as “most like the gods” but praised primarily for his humanitas (humanity).

Relief panel from Dendera, depicting Emperor Trajan in Egyptian guise making offerings to Hathor. Credits: Aidan McRae Thomson, CC BY-SA 2.0

Through paradoxical depictions, Pliny creates a multi-dimensional portrait of Trajan that celebrates his unprecedented ability to embody contradictory virtues harmoniously. This innovative rhetorical style underscores the transformation of imperial ethics, positioning Trajan as an emperor unlike any before him—a model of leadership, morality, and humanity. (To be and not to be: Pliny's Paradoxical Trajan, by Roger Rees)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: