Rethinking Lucius Verus through Sources and Historiography

Lucius Verus is often overshadowed by his co-emperοr, Marcus Aurelius, but his rich in contrast and character biography deserves a deep dive.

He dined in silk, amused himself with actors, and rode in gilded carriages—hardly the image of the Roman emperor forged in marble and sweat. And yet, Lucius Verus ruled an empire.

Crowned not alone but beside Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-king, Lucius has been cast as the indulgent shadow to his co-emperor’s stoic light. But was he truly so unworthy? Behind the rumors of luxury and pleasure lies a man entrusted with war, celebrated in triumph, and mourned by Rome; the story of an emperor history chose to forget.

People remember Marcus Aurelius as the philosopher-emperor, the Stoic ideal, a ruler of discipline and thought. At his side, however, stood Lucius Verus—Rome’s first official co-emperor, a man celebrated in his own time but largely forgotten by posterity.

Eclipsed by the moral gravity of his adoptive brother, Lucius has often been dismissed as a mere companion to greatness: indulgent, ornamental, and idle. But a closer look reveals a figure far more complex—a prince of ease thrust into war, a ruler whose reign deserves more than footnotes and faint judgment.

Reconstructing Lucius Verus: Sources, Shadows, and the Story of a Co-Emperor

When it comes to Lucius Verus, the historical record is fragmented and often filtered through moral judgment or imperial propaganda. There is no rich archive of letters or detailed chronicle from a major historian devoted to him.

Instead, our understanding must be pieced together from diverse and often contradictory sources: the Historia Augusta, letters from Marcus Cornelius Fronto, Cassius Dio's fragments, later Roman historians like Eutropius and Festus, archaeological and epigraphic evidence, coinage, and even legal and Christian texts. Each offers glimpses, sometimes distorted, of an emperor remembered as much for his pleasures, as for his power.

A Patchwork of Sources

The most substantial literary account comes from the Historia Augusta, particularly the biography dedicated to Verus and related ones on Marcus Aurelius and Antoninus Pius. Its reliability varies wildly, ranging from precise details to imaginative embellishment. Still, it's clear the work had a propagandistic aim, appealing to a popular audience. This slant is particularly visible in how Verus is portrayed: his lifestyle and personal habits consistently color assessments of his reign.

The Historia Augusta is widely debated among scholars. Today’s consensus holds that it was the work of a single fourth-century author writing under multiple pseudonyms.

For a more personal and sympathetic view, we turn to the letters of Marcus Cornelius Fronto, a rhetorician who taught both Marcus and Lucius. Cassius Dio offers select, though fragmented, details, and Christian writers like Eusebius and Orosius preserve later interpretations. Archaeology, art history, and coinage add texture and context, while even legal compilations like the Code of Justinian preserve traces of imperial administration.

Family and Early Life

Lucius Verus, born Lucius Ceionius Commodus in December 130, was the son of Lucius Aelius Caesar—Hadrian's original successor. After Aelius Caesar died on January 1, 138, Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius, who in turn was required to adopt both Marcus Aurelius and young Lucius. Lucius was betrothed to Hadrian's daughter Faustina, a plan later undone when Antoninus came to power.

Lucius received a thorough education in Latin and Greek, under grammarians and later more advanced tutors, including Fronto, as well as philosophers like Apollonius of Chalcedon and Sextus of Chaeronea. He was well-liked, described as charming and strikingly handsome. His name changed over time, eventually becoming Lucius Aurelius Verus after Marcus gave him the name Verus in 161 to establish a familial connection.

Despite being reared with Marcus, Lucius was often treated as inferior—his status underscored by protocol in public appearances. Still, he was fast-tracked through political offices: quaestor in 153 (a year early), consul in 154 (nine years early), and again in 161 alongside Marcus.

Co-Emperorship and the Parthian War

When Antoninus died in 161, Marcus became emperor and insisted that Lucius be made co-emperor—a historic first. Officially they ruled as equals, but Marcus, holding the title of pontifex maximus, clearly held greater authority. Their joint rule began at a time of floods, famine, and war in the East.

Marcus arranged for Lucius to marry his daughter, Lucilla, and shortly after, Lucius departed for the Parthian front. According to the Historia Augusta, his journey to Syria was marked more by indulgence than urgency. He became ill in southern Italy, prompting Marcus to visit him, but Lucius recovered and continued east. He lingered in cities like Corinth and Athens, enjoying entertainment, and eventually set up his base in coastal Syria—away from the frontline.

Marcus had the foresight to appoint Avidius Cassius and other capable generals to handle the actual fighting.

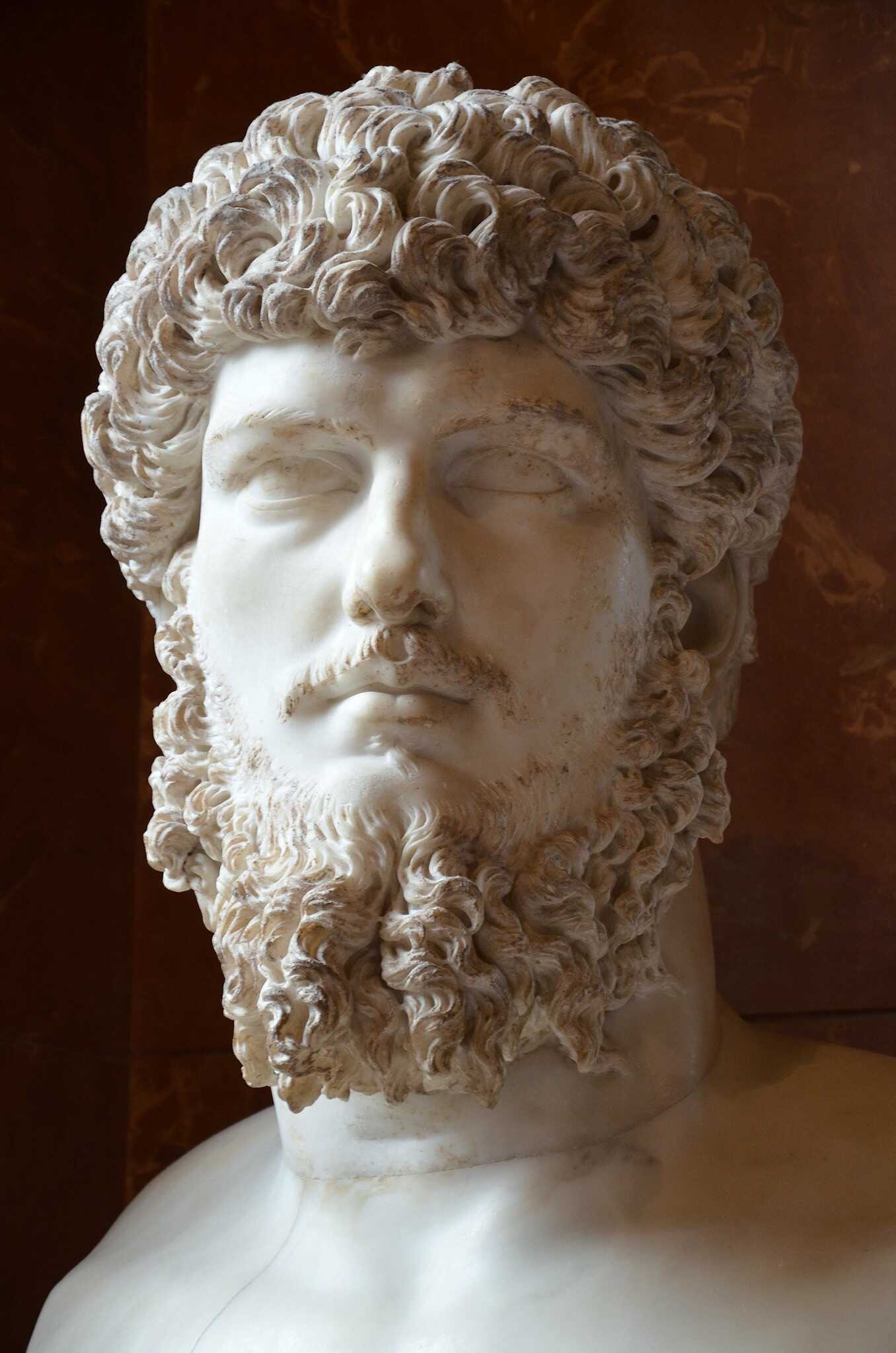

Bust of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Credits: Nickmard Khoey Historical Archive, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Cassius Dio and Eutropius both credit Lucius with wisely delegating authority and ensuring supplies, even if he remained at a distance. Fronto praised his efforts to maintain troop morale. In the end, the Parthian War was a Roman success, and both emperors celebrated a joint triumph in October 166, parading alongside their children and in full view of the public.

Life in Rome and the Germanic Threat

Upon returning, Lucius brought his Syrian entourage of actors and entertainers back with him. His lifestyle—parties, taverns, disguises, and gambling—shocked conservative Roman sensibilities. According to the Historia Augusta, he had a tavern built in his home and indulged in lavish entertainments.

Marcus disapproved but remained tolerant, even accepting an invitation to stay at Lucius's villa, where the two shared little in terms of daily routine. Despite this excess, Marcus continued to support Lucius, even taking him to the northern front when Germanic tribes began pressing into Roman territory. Marcus had learned that Lucius left unsupervised was a political liability.

In 169, as they returned from the Danubian front, Lucius fell seriously ill near Altinum. After being bled and carried into the town, he died within three days at age 38. Rumors of poisoning circulated—some implicating Faustina, others Marcus himself—but these have no basis in reliable evidence.

Marcus mourned his brother deeply. He brought the body back to Rome, oversaw the funeral, ensured the care of Lucius's family and household, and had him deified as Divus Verus. Despite his reputation for excess, Lucius Verus was not discarded by history; he was given imperial honors, enshrined in memory, and, in his own way, held fast to the Roman ideal of public image, family legacy, and shared power.

The Adoption that wasn’t: Hadrian, Lucius, and the Imperial Succession

When Emperor Hadrian named Lucius Ceionius Commodus as his heir in 136 AD, it appeared to follow a familiar Roman pattern: an aging ruler adopting a successor to secure the future of the empire. And yet, as historian T.D. Barnes argues in his article "Hadrian and Lucius Caesar" (1967), what Hadrian did was far less clear-cut. Despite the widespread assumption that Lucius was formally adopted, the historical record tells a different story—one of symbolism, politics, and image rather than law.

Hadrian's Heir: More Designation than Adoption

As Hadrian's health declined in the mid-130s, the need for a successor became urgent. In 136 AD as aforementioned, he chose Lucius Ceionius Commodus, later renamed Lucius Aelius Caesar. Many historians have long claimed this involved a formal legal adoption. But Barnes carefully examines the language of imperial titles, inscriptions, and coinage and finds no evidence for such a legal move.

In fact, Hadrian never used the formal language associated with Roman adoption. Lucius was given the title of "Caesar" and referred to as "son" in an honorific sense, but not in the precise legal framework used when, for example, Antoninus Pius was adopted. Barnes distinguishes between designation (naming someone as heir) and adoption (making them legally your child), arguing that Lucius was the former, not the latter.

Titles, Coins, and what they tell us

Barnes points to imperial coinage and official inscriptions. When Hadrian later adopted Antoninus Pius, the language on coins and monuments was exact: Antoninus was called "filius Augusti" (son of the emperor) and adoption was clearly stated. Lucius, on the other hand, was never referred to with such legal terminology. The titles he held were imperial and prestigious, but politically symbolic—not legally binding.

“Antoninus Pius is explicitly named as Hadrian’s adopted son — filius Augusti — in both inscriptions and coinage, whereas Lucius is not.”

T.D. Barnes

This suggests that Hadrian intended to signal his choice of Lucius as heir publicly, but without undergoing the formalities of adoption. It was a move designed to influence perception more than fulfill legal obligations.

Image #1: Roman Aureus Gold Coin depicting co-Emperor Lucius Verus, notice the absence of the Filius Augustus (AUG) on the top left. Image #2: Roman Aureus Gold Coin depicting Emperor Antoninus Pius, with the Filius Augustus (AUGFI) on the top left Credits: Roman Empire Times, Marina Fischer, CC BY-NC 2.0

An Unusual Candidate

Lucius himself was a surprising choice. He lacked significant military or political experience and was viewed as an unremarkable figure. Barnes notes that Lucius's father had been a close associate of Hadrian, which may have influenced the decision. Ancient sources, such as Cassius Dio, indicate that Hadrian’s choice was unexpected and controversial. Some even believed Hadrian was mentally unstable at the time.

“It was thought by many that Hadrian was not in his right mind when he selected Ceionius.”

Dio, Roman History 69.21

Enter Antoninus and the Dynastic Workaround

Lucius Aelius Caesar died suddenly in 138 AD, just months before Hadrian himself. In response, Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius as his new heir. But to preserve the symbolic dynastic line, Hadrian required Antoninus to adopt two young men: Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, the biological son of Lucius Aelius Caesar.

This political maneuver shows that Hadrian was deeply invested in the appearance of dynastic continuity.

A sketch of a portrait of Roman Emperor Hadrian, from Arturo Espinosa. CC BY 2.0

Even if Lucius had not been formally adopted, his bloodline would continue in the imperial office through his son. Barnes challenges earlier historians, such as Mommsen, who had assumed a legal adoption based on inference rather than evidence. He insists on paying close attention to the actual language in coins, inscriptions, and Roman law. His conclusion is clear: Hadrian did not legally adopt Lucius Ceionius Commodus.

Instead, he granted him honorific titles and publicly designated him heir. The distinction, though subtle, has major implications for how we view succession politics in the Roman Empire.

Ultimately, Barnes reveals a Rome where public image and imperial symbolism often outweighed strict legal procedures. Hadrian’s actions were about crafting a vision of stability and continuity for an empire that prized both tradition and adaptability. In naming Lucius, Hadrian sent a message to the Senate, the army, and the Roman people. But the fine print of that message—as Barnes shows us—was far more nuanced than we once believed.

“In short, my achievements, whatsoever their character, are no greater, of course, than they actually are, but they can be made to seem as great as you would have them seem”.

Lucius to Fronto, Ad Verum Imp. 2.3

In the Shadow of a Philosopher

To modern readers, Marcus Aurelius’s decision to share imperial rule with Lucius Verus may seem unusual, perhaps even puzzling. Was this a strategic choice by a wise emperor who understood the challenges of ruling a vast empire? Or a philosopher-emperor delegating military burdens, so he could focus on higher ideals?

Neither extreme fully explains the situation. While circumstance played a part, the most likely reason lies in trust—Marcus had known Lucius since childhood and believed in his capacity to govern. Regardless of whether he wanted to avoid military matters or saw real talent in Lucius, Marcus clearly judged him fit to rule.

When we move past the exaggerated portrayals found in sources like the Historia Augusta, a different image of Lucius emerges. He appears not as a caricature of luxury and indulgence, but as a capable administrator with a penchant for the good life. The sharp contrast often drawn between Marcus and Lucius may be less reflective of reality than of the biases of later writers who benefited from simplifying their dynamic into a moral tale of virtue and vice.

Lucius did not lead the Parthian campaign like Trajan, hands-on and in the thick of battle. Nor did he remain entirely removed like Antoninus Pius had in earlier conflicts. He was present in the East, surrounded by skilled generals like Avidius Cassius, and played a logistical and administrative role that contributed meaningfully to Rome's success.

In his correspondence with Fronto, Lucius expresses confidence, gratitude, and strategic awareness. He valued the commanders under him and supported efforts to record the campaign for posterity. Roman coinage, public titles like Armeniacus, Parthicus, and Medicus, and public enthusiasm all attest to the importance of his contribution.

Fronto himself once praised Antoninus Pius with these words:

"Although he had committed the conduct of the campaign to others while sitting at home himself in the Palace at Rome, yet like the helmsman at the tiller of a ship of war, the glory of the whole navigation and voyage belonged to him."

From the Speech on the War on Britain

This analogy could apply just as well to Lucius, who was in the region, managing the campaign while letting his generals handle the fighting. If that kind of remote leadership earned Antoninus glory, surely Lucius’s role deserved no less.

The Historia Augusta mocks him as a hedonist, yet contemporary sources suggest he was celebrated at the time. The key difference is one of narrative: Marcus was remembered as Rome's final 'good' emperor, while Lucius was cast as the foil who made him shine brighter. But Marcus’s own writings contradict this binary. In the Meditations, he wrote:

"Lucius Verus... was able by his moral character to rouse me to vigilance over myself, and pleased me by his respect and affection."

His apotheosis of Lucius after death further reinforces that esteem.

Apotheosis of Lucius Verus, on Helios’ chariot driven by Nike. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

So where did the negative portrayal originate? Possibly from later authors who wanted to elevate Marcus further, using the contrast with Lucius to frame him as near-perfect. The Historia Augusta, like a tabloid, trafficked in oversimplification and melodrama. Or perhaps the attacks came later still, during Commodus’s reign, when Lucius’s widow Lucilla was caught in a failed conspiracy. Smearing her late husband may have been part of the political fallout.

Whatever the source, Lucius became a victim of historical distortion. His enjoyment of life, oratorical skill, and competent management were spun into vices. His logistical role in warfare was dismissed as laziness. His absence from battlefronts was framed as cowardice, while Marcus's similar choices were accepted as prudence. Some have even suggested that Lucius’s flamboyance stemmed from resentment: Antoninus Pius had favored Marcus, and Lucius may have sought identity through his birth father, Aelius Caesar, rather than the adoptive father who seemed to overlook him.

This sense of alienation may have shaped his personality and public image, down to the distinct style of beard worn in homage to his real father.

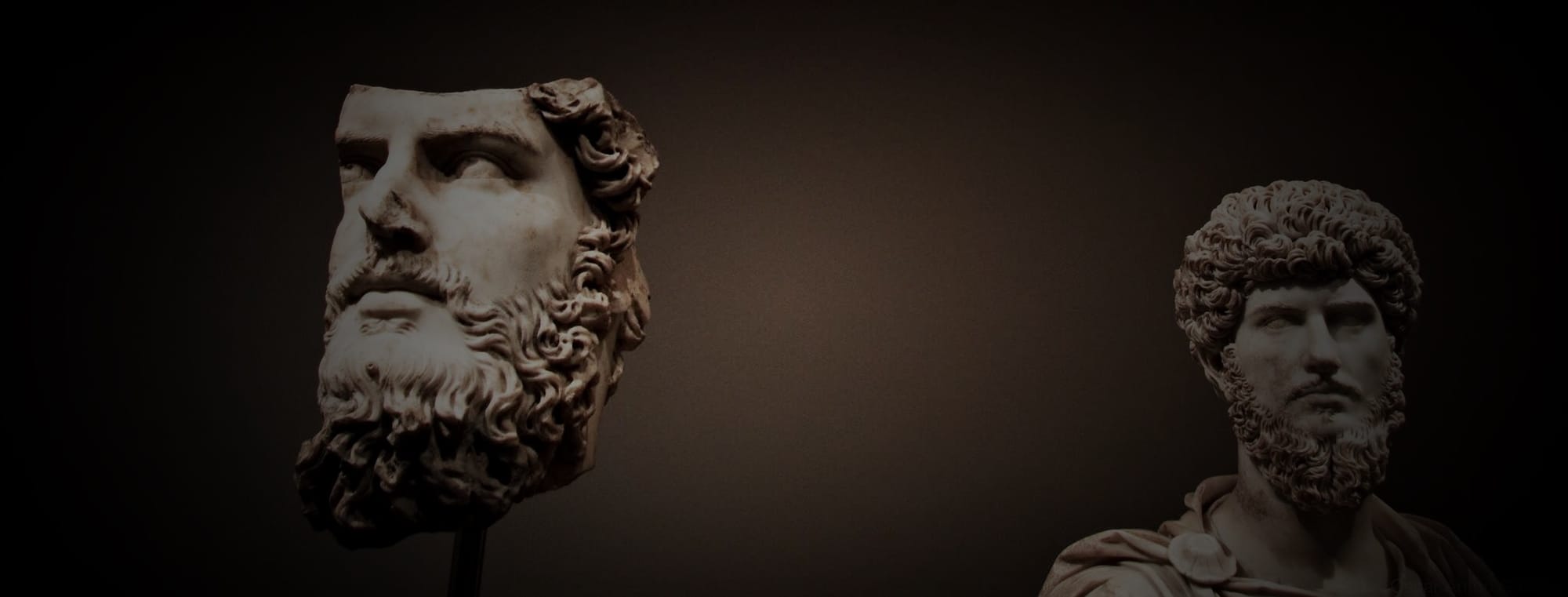

Busts of Lucius Verus. Credits: Oscan Anton, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The legacy of Lucius Verus deserves better. When we set aside the stylized hagiography of Marcus and strip away the theatrical criticisms of Lucius, we see two men who ruled effectively together, at a time of serious threats to Rome. The Parthian conflict was quelled. A Germanic incursion was held at bay. And though Lucius died before the worst of the Marcomannic Wars unfolded, he was never seen by his brother or his people as unworthy. He was, in his lifetime, respected and celebrated.

That later generations chose to tell his story as a moral contrast says more about their values than about Lucius Verus. In truth, he and Marcus were not opposites, but partners; Rome’s first true co-emperors. And it’s time history remembered them that way. (Lucius Verus and the Roman defense of the east, by M.C Bishop)

Lucius Verus did not leave behind a philosophical legacy. But he left behind victories, reforms, and an empire that remembered him with honor. If history has veiled him in shadow, it is time we allowed his own light to shine.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: