Pompey the Great: The Partner and Rival of Julius Caesar

Pompey the Great, or Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, was one of the most prominent Roman military and political leaders during the late Roman Republic.

To later generations of Romans, the three decades between the dictatorships of Sulla and Caesar were known as the age of Pompey the Great. Despite this period being a central focus in Roman history courses in schools and universities, it is surprising that there has not been a comprehensive study of Pompey, its most prominent figure. As a result, for many people, Pompey remains an enigmatic and less vivid figure compared to the more well-known Cicero and Caesar.

The Life of Pompey

Pompey was born into a noble family and was the son of Pompeius Strabo, a general and consul. He began his career in the military during the Social War, earning a reputation as a capable commander. His early success came when he aligned himself with Lucius Cornelius Sulla during the civil war between Sulla and Marius in the late 80s BC. Pompey’s support for Sulla and his military victories earned him the nickname “Magnus” (The Great), a title Sulla gave him.

Although the late Roman Republic is a familiar period, Pompey the Great remains somewhat elusive compared to figures like Julius Caesar and Cicero. His vast fame has overshadowed the man himself, and he is often seen as a background figure, even though he played a central role in Roman history.

One of Pompey’s greatest flaws was his inability to perceive the imminent collapse of the Republic, blinded by his own sense of importance and lack of political insight. While he possessed solid military abilities, he lacked the genius and foresight that defined other great leaders.

Despite this, Pompey’s early career was marked by significant achievements. He was instrumental in subduing three continents, including his decisive campaign against Mediterranean pirates, which took just three months. His military victories in Africa, Spain, and the East established his reputation, and he returned to Rome to celebrate multiple triumphs.

However, Pompey struggled politically, lacking the instincts and acumen needed to navigate the increasingly complex Roman political landscape. His relationship with the Optimates, the Roman elite, was tenuous, and he often made missteps, such as supporting the controversial democrat Lepidus.

As he aged, Pompey’s political and military effectiveness declined. Despite his marriage to Caesar’s daughter Julia and their brief political alliance through the First Triumvirate, his relationship with Caesar deteriorated. After Julia’s death, Pompey became the Senate's chief hope against Caesar, but by then, he had lost much of his old vigor and authority.

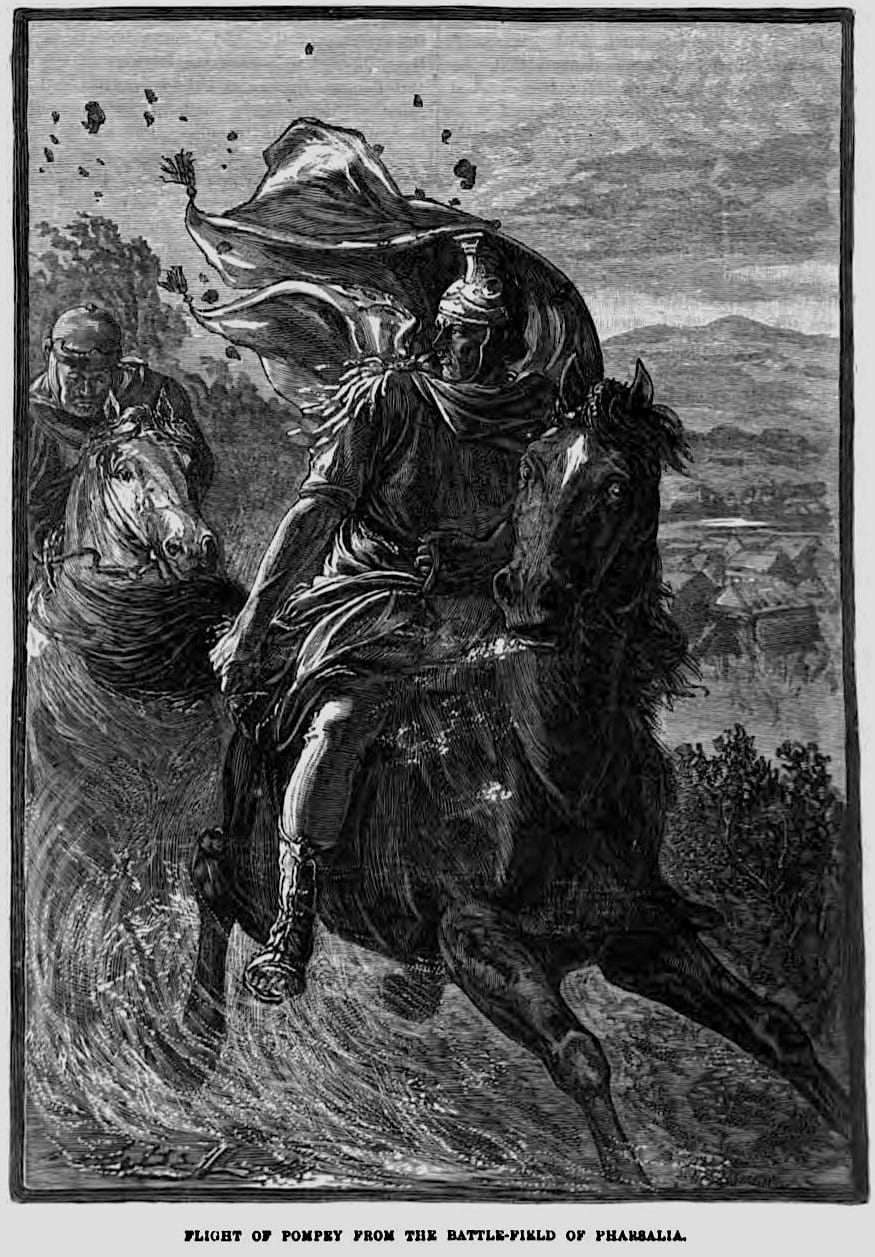

In 48 BC, his forces were decisively defeated by Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus. Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was murdered, a pitiful end to a once-glorious career.

Image #1: Pompey the Great

Image #2: Crassus

Image #3: Julius Caesar

Credits: Gautier Poupeau, CC BY 2.0/Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

Pompey's Military Glory

Pompey's early career was shaped by his role in the Social War, but it was his campaigns during the Roman civil wars and later against the Mediterranean pirates that solidified his reputation as one of Rome’s greatest commanders.

- Victories in the Civil War Against Marius’ Forces (83-81 BC): Pompey’s rise began with his support of Sulla during the civil wars. He raised three legions from his family’s estates and won crucial battles in Sicily and Africa against the remaining Marian forces. His success in these conflicts earned him his first triumph despite his young age and lack of formal political experience. It was also during this period that he was given the title Magnus (the Great), a recognition of his early successes in restoring Sulla’s dominance.

- Defeat of the Pirates (67 BC): One of Pompey's greatest achievements was his swift and decisive campaign against the pirates who had become a scourge in the Mediterranean. The Senate gave Pompey extraordinary powers to eliminate the threat, and he divided the Mediterranean into sectors, systematically clearing the sea of pirates in a matter of months. This victory not only restored safe sea routes but also cemented Pompey’s position as Rome’s foremost military leader.

- Mithridatic Wars (66-63 BC): Following his success against the pirates, Pompey was given command of Rome's war against King Mithridates VI of Pontus. Pompey decisively defeated Mithridates, expanded Roman control in the East, and reorganized the territories to become Roman provinces. His victories over Mithridates and his political reorganization of the Eastern Mediterranean showcased his brilliance as a strategist and administrator.

These victories, along with his role in defeating Spartacus and later battling Julius Caesar, contributed to Pompey’s enduring legacy as one of the most formidable military leaders of the late Roman Republic. (Pompey: Leadership, strategy, conflict, by Nick Fields)

The Alliance with Caesar

The political setbacks of 61 and 60 BC convinced Pompey that the use of force, or at least the threat of it, was necessary to achieve his goals. The opportunity arose in early 59 BC during Caesar’s consulship, when Caesar introduced an agrarian bill aimed at distributing public land in Italy to veterans and the unemployed. Despite efforts to avoid threatening private property or state finances, opposition from figures like Cato led Caesar to bypass the Senate and take the bill directly to the assembly.

At a public meeting to discuss the bill, Bibulus, the other consul, vowed to block it, even if the people supported it. In response, Pompey, urged by Caesar, accused the Senate of jealousy and inconsistency, pointing out that the policy had been agreed upon in 70 BC, but lacked funding then. Pompey’s famous line, "If anyone dares to raise a sword, I too will take up my shield," cleverly positioned any use of force as being in defense of the people.

When Bibulus attempted to veto the vote, Pompey and Caesar were prepared. Armed veterans filled the assembly, and Bibulus was forcibly removed, after which the bill was passed. In February, the Eastern settlement was ratified, facilitated by Caesar’s loyal tribune, Publius Vatinius, who managed negotiations with various kings and cities.

Pompey also secured financial benefits by extracting a promise of nearly 150 million sesterces from Egypt’s Ptolemy XII in exchange for support in the Senate. Although Pompey had finally triumphed over his opponents, including Cato and Lucullus, Cicero remained a threat. Pompey and Caesar responded by enabling Clodius, a known enemy of Cicero, to be adopted into a plebeian family, which allowed him to become a tribune and later pass a law that threatened Cicero with exile.

Despite his victory, Pompey faced growing unpopularity among senators and equites, and his partnership with Clodius, though necessary, was personally distasteful. By April, Cicero’s letters began to reflect the increasing dissatisfaction with the triumvirs, especially Pompey, who bore the brunt of public criticism.

“Do you approve of Caesar’s laws?

Yes.

What about their legality?

Caesar must take responsibility for that.

Yes, I approve of the agrarian law, but it is no business of mine whether a veto was possible or not.

Yes, I’m glad that the Egyptian king’s position has been finally settled.

Was Bibulus watching for bad omens at the time?

It was not my business to enquire.

What is your view of the recent settlement in favour of the publicanil?

I have been anxious to oblige that order.

What would have happened if Bibulus had come down to the Forum on that occasion?

I can’t prophesy the answer to that one.”

Cicero reported that Pompey was becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the political situation and seemed to be distancing himself from any illegal actions, shifting the blame onto Caesar. Pompey and his allies were being labeled as "tyrants" by their opponents.

In late April, three significant events occurred:

- Caesar introduced a second agrarian bill to redistribute land in Campania to veterans and poor citizens,

- Bibulus attempted to block the upcoming elections and retired to his house, launching a campaign against the triumvirs,

- and Caesar offered Pompey his daughter Julia in marriage to secure Pompey's support.

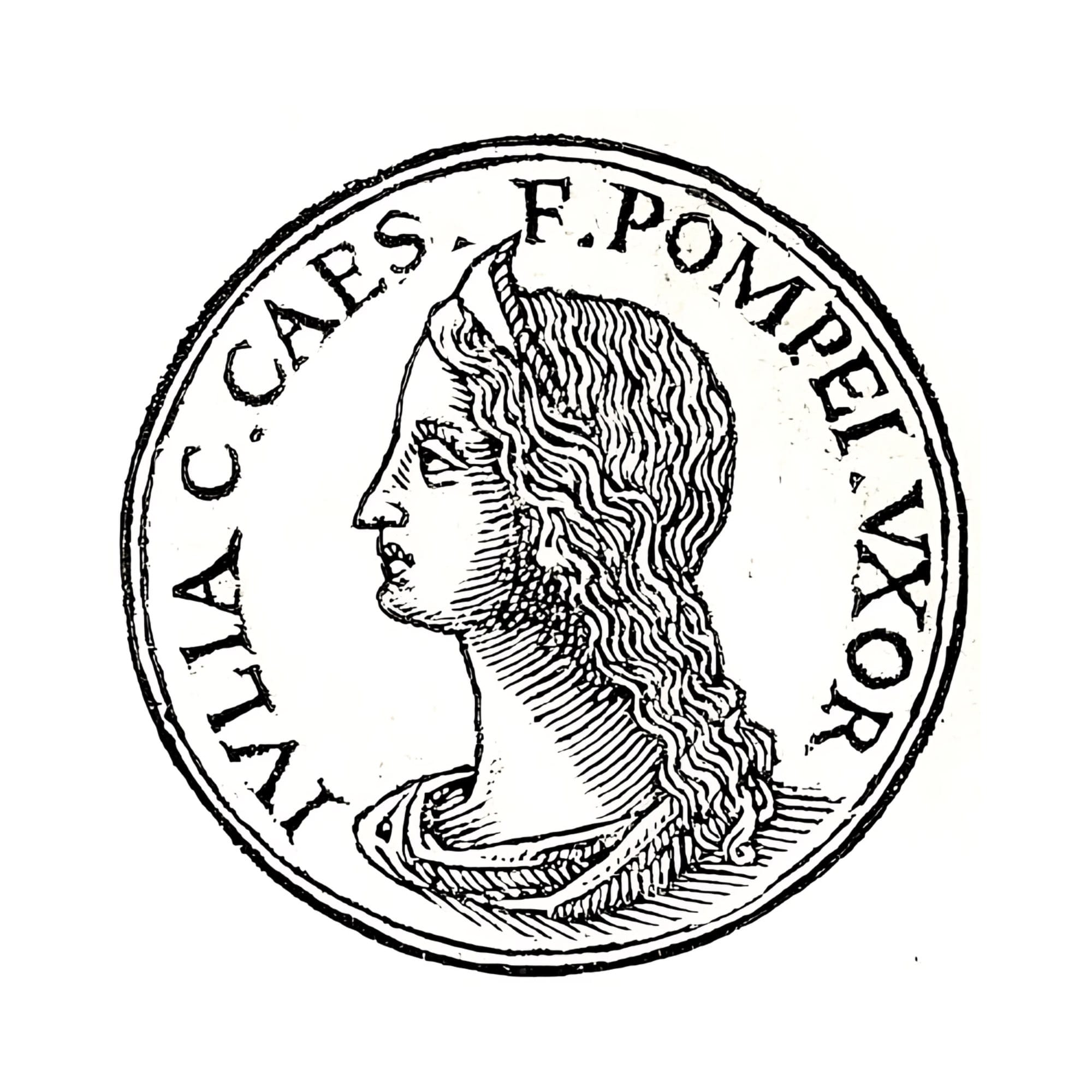

The marriage between Pompey and Julia, though an unexpected match, proved successful.

Julia Caesaris was the daughter of Caesar by his first wife, Cornelia Cinna, and his only child in marriage. Julia was renowned for her beauty and virtue. Public domain

Pompey worked closely with his new father-in-law, and Caesar secured a five-year command in Gaul. In May, Bibulus warned Pompey of a plot against his life, but the details remain unclear. Later in the summer, the consular C. Scribonius Curio revealed that Pompey's son had been approached to join an assassination plot involving Lucius Vettius, a spy. Vettius was brought before the Senate and gave a modified confession, implicating several prominent individuals, but was found strangled in prison before a full investigation could take place.

Cicero and others dismissed the existence of any real plot, viewing the incident as a manipulation by Caesar to incriminate his opponents. Despite the unclear details, Pompey may have thwarted an assassination attempt. The events contributed to increasing tension, and by mid-59 BC, Pompey had become unpopular among many politicians and was labeled a "tyrant" by his critics.

The triumvirs were trying to secure control over the upcoming consular elections with the help of bribery, aiming to place their allies in power to protect Caesar’s position during his upcoming campaigns. Pompey returned to Rome before the elections, only to face further opposition from Bibulus, who postponed them.

“So you can picture our friend. Unused to losing his reputation, always surrounded in the past by admiration and fame, he is now crippled in body and broken in spirit, and has no idea which way to turn.

To carry on the way he is going would bring him to the edge of the precipice, to go back would brand him as a renegade, and he sees this. The boni are his enemies and their rascally opponents aren’t his friends.

Look at my soft-heartedness: I couldn’t control my tears when I saw him speaking at a public meeting on Bibulus’ edicts on 25 July. In the past he used to play to the gallery so magnificently from that rostrum, before an adoring crowd, with everyone on his side.

But this time he was so humiliated, so downcast, so dissatisfied with himself. The audience shared his opinion, but the only one who can have taken any pleasure from the sight was Crassus.

Certainly no one else did.

He has fallen from his rank among the stars, but it does look like an accident rather than his own fault… Nobody thought that I ought to remain on friendly terms with him, because of that Clodius business, but my own affection for him was too great to be whittled away by some injury.

Bibulus’ Archilochian [scathing] edicts against him are so popular that you can’t get past the place where they are posted for the crowd of people reading them, but they are such a bitter pill for him to swallow that he is visibly wasting away with unhappiness.

I also find them unpleasant, because they cause too much pain to someone I have always been fond of, and I am afraid that he may lose all self-restraint and give in to his resentment and anger.

He is an impetuous man and a fierce fighter, and he is not used to such insults”

What must have been most frustrating for Pompey was the loss of dignity and prestige he was facing, something he likely recognized was largely due to his support for Caesar's policies. Given his position as the most prominent public figure among the three, many naturally viewed him as their leader.

According to Cicero, many of Crassus and Caesar's supporters, known as the improbi or rascally opponents of the boni, were turning against Pompey. It was evident that neither Crassus nor Clodius was willing to help him. In this difficult situation, Pompey sought the assistance of Cicero, a politician whose friendship he had always been able to secure when needed. Cicero believed the coalition between Pompey, Caesar, and Crassus was starting to fall apart. It is generally thought that Pompey's solution was to break ties with Caesar and reconcile with the Optimates, with the hope of using Cicero as an intermediary.

The Conflict with Caesar

During 54 and 53 BC, Pompey rose to an unprecedented level of prominence in Roman politics, despite events damaging the Republic's institutions and amplifying violence in the political arena.

As competition among politicians intensified, bribery and corruption surged, exemplified by the scandal surrounding the consular elections of 53. Pompey favored M. Aemilius Scaurus, but upon discovering corruption, he exposed the scandal, possibly aiming to delay the elections, which led to speculation that he sought a dictatorship. However, Pompey denied such intentions.

The deaths of Pompey’s wife Julia in 54 and Gabinius' trial in 53 further complicated matters. Pompey, though grieving, attempted to protect Gabinius but was only partially successful. During this time, Rome descended into further violence and instability, leading to a call for Pompey to assume dictatorial powers. However, Pompey refused and instead was made sole consul, an unusual and unconstitutional position.

As sole consul, Pompey swiftly acted to restore order by bringing troops into Rome and passing strict laws against bribery and violence. This crackdown led to a series of prosecutions, including the condemnation of Milo. Despite some criticism, Pompey's actions brought temporary stability to Rome.

However, his relationship with Caesar began to fray. Though Pompey had not yet broken with Caesar, the two were drifting apart, especially as Pompey extended his military command in Spain and maneuvered politically to maintain dominance without directly confronting Caesar. (Pompey the Great, Routledge Revivals by John Leach)

The Decisive Battle at Pharsalus

In 55 B.C., Pompey and Crassus were once again elected consuls amid significant violence, pushing forward minor reforms and extending Caesar’s command in Gaul until 49 B.C. While Pompey was appointed to Spain, he kept his army in Italy, an irregular move that foreshadowed tensions to come. His intervention in Egypt, reinstating Ptolemy Auletes as Pharaoh, would later contribute to his downfall.

With Crassus dead in Armenia and Caesar expanding his conquests in the west, political turmoil erupted in Rome. In 52 B.C., Pompey was made sole consul, mirroring Caesar’s later dictatorship but lacking long-term vision. Despite attempts to reform the electoral and legal systems, Pompey exempted Caesar from key decrees, a move Tacitus critiqued as Pompey undermining his own laws.

Pompey’s health began to fail, but he regained popularity through a tour of Italy. By 50 B.C., Caesar was preparing for his consulship bid, and Pompey, appointed to defend Italy, underestimated the threat posed by Caesar, famously claiming that he could raise legions by simply stamping his foot.

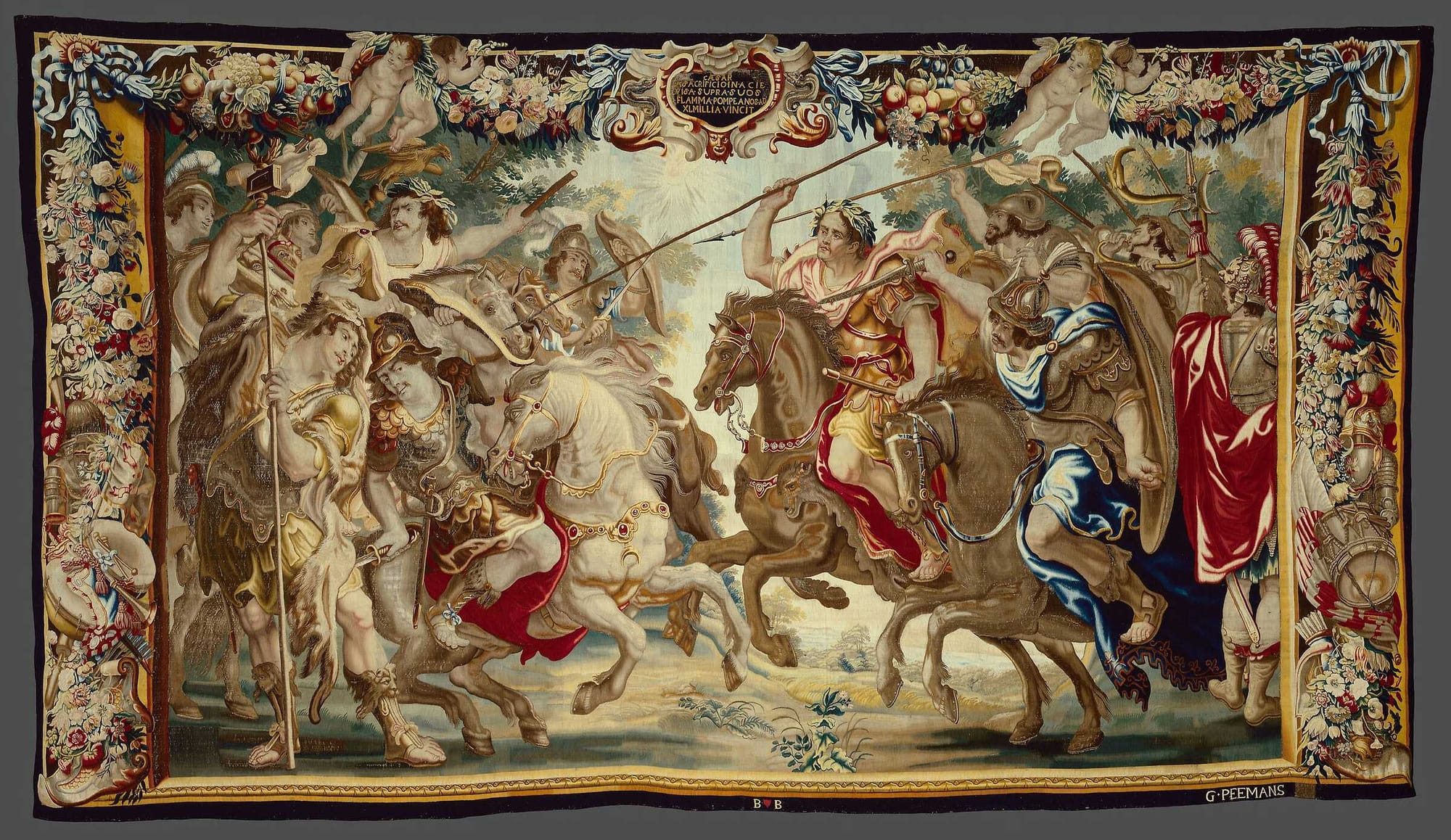

When Caesar crossed the Rubicon in January 49 B.C., Pompey fled to the east, preparing for confrontation. Despite a large but poorly organized force, Pompey’s leadership faltered. At the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C., his superior cavalry was overwhelmed by Caesar’s well-trained infantry, leading to Pompey’s decisive defeat. (Decline and Fall of Pompey the Great, by H. P. Collins)

The Turning Point of the Battle

We don't know the exact amount of time Pompeius waited before ordering the cavalry to charge. Caesar's narrative suggests it occurred shortly after the initial contact between the forces. However, Plutarch says:

"After Crastinus had fallen, the battle was evenly contested at this

point; Pompeius, however, did not lead up his right wing swiftly, but

kept looking anxiously towards the other parts of the field, and

awaited the action of his cavalry on the left, thus losing time."

Pompey likely waited to ensure that his untested front line could withstand Caesar’s initial attack and that Caesar’s forces were fully engaged in the battle. Once he was confident, he gave the command to unleash his cavalry, archers, and slingers against Caesar’s right flank. This wasn't only because Caesar was positioned there, but also because it was the only side with enough space for such an assault and for turning the flank toward the center. By doing this, Pompeius deployed what both armies saw as his greatest strength, initiating the critical phase of the battle.

The battle unfolded as anticipated by both sides. Caesar’s right flank initially buckled under the pressure of Pompey’s superior cavalry and projectile units. In a traditional scenario, this would have led to a collapse of the Caesarian forces, allowing Pompey to encircle and annihilate them.

However, Caesar had anticipated this move and deployed a fourth line of specially trained infantry units, tasked with countering Pompey' cavalry. This was a bold and uncertain tactic, especially given the large numbers involved and the presence of archers and slingers in Pompeius' forces.

Caesar’s gamble hinged on whether these infantry units, totaling around 3,000 men, could repel the cavalry charge, which numbered about 7,000. The outcome was pivotal: either Pompey' cavalry would overwhelm Caesar’s flank, or the infantry would hold their ground and turn the tide.

The gamble paid off. Caesar’s infantry used their pila, aiming for the riders' faces, and the cavalry, unable to regroup, dispersed in disarray. This left Pompey' slingers and archers exposed, and they were swiftly overwhelmed and massacred by Caesar's forces. With Pompey' cavalry and projectile units neutralized, the battle turned into a straightforward infantry confrontation, where Caesar’s forces had the upper hand.

Although Pompey' initial defeat on his left wing was significant, it did not immediately determine the outcome of the battle. Victory would depend on which commander could react quickest to the developments on this weakened flank. Pompey needed to reinforce his left wing, while Caesar aimed to exploit his newfound advantage. According to Caesar’s account, the smaller, more compact nature of his forces gave him the upper hand in reacting swiftly to these events. Caesar recounts:

"With the same onslaught the cohorts surrounded the left wing, the Pompeians still fighting and continuing their resistance in their lines, and attacked them in the rear.

At the same time Caesar ordered the third line, which had been undisturbed and up to that time had retained its position, to advance. So, as they had come up fresh and vigorous in place of the exhausted troops, while others were attacking in the rear, the Pompeians could not hold their ground and turned to flight in mass.

‘Pompeius, when he saw his cavalry beaten back and that part of his force in which he had most confidence panic-stricken, mistrusting he rest also, left the field and straightway rode off to the camp."

Pompey’ left wing, now without its cavalry and archers, was easily surrounded and attacked from the rear by Caesar’s Tenth Legion. Caesar's third line, which had remained fresh, was deployed to replace his exhausted troops. This timely maneuver ensured that Pompey’ forces were unable to bring reinforcements fast enough from his reserves.

Despite Pompey having a larger army, many of his forces were multi-national and seemingly slower to respond. Caesar, with a smaller and more unified force, was able to adapt quickly to the battlefield's changing dynamics. His ability to exploit the weaknesses of Pompey' army and terrain—particularly the river restricting Pompey' movements—played a critical role in his eventual victory. Caesar’s forces managed to hold the left and center, maintaining the battle's focus on his right wing, where he had the advantage.

Pompey's End

Although Pompey could have been remembered as a great leader and the builder of the Roman Empire, he instead became a tragic figure, eclipsed by Caesar and the dramatic fall of the Republic. Historians often struggle to fully grasp his character, as he lacked the moral and intellectual depth of figures like Cato or Cicero.

After his defeat at Pharsalus, he fled on horseback with a few companions to the mouth of the Peneus and then set sail in a small boat to Mitylene, where his wife Cornelia awaited him. Plutarch describes Cornelia's deep grief and self-blame upon seeing him. Pompey briefly regained some of his old confidence, assembling a fleet and attempting to reorganize his eastern resources.

Unfortunately, he decided to seek temporary refuge with the young king of Egypt, Ptolemy Auletes' son. The king's mercenaries and advisers were torn between fear of Caesar’s wrath and hesitation to reject such a renowned figure. Achillas, a soldier of fortune, suggested that killing Pompey would please Caesar, as "dead men do not bite."

A galley was sent to welcome Pompey, and as Cornelia watched from afar, he was rowed ashore. He walked into a trap, unaware of the impending danger. Once on land, he was stabbed multiple times from behind, falling silently and covering his face with his cloak. His head was cut off, and his body thrown into the sea, later retrieved by two humble Romans who gave him a rough cremation using the remains of a derelict boat as a pyre.

Ultimately, the strong dictatorship of someone like Caesar was inevitable.

Julius Caesar, showing remorse when presented with Pompey's severed head, a common theme for late European paintings and art. Credits: Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, Public domain

Thus ended the life of Pompey the Great, one of the most constitutional and humane conquerors, yet unable to bear the burden of his own significance. Though he added prestige to the dying Roman Republic, he lacked the vision and selflessness to prevent its fall. If he had won at Pharsalus, Rome’s constitutional government might have lasted a little longer, but its corruption and the unrest of the masses made its survival unlikely.

While Pompey may inspire sympathy for his commitment to the Republic, he was not the kind of leader capable of guiding Rome through the changes it faced. Caesar, with his foresight, was better suited for that role. (Decline and Fall of Pompey the Great, by H. P. Collins)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: