Pliny the Younger: The 247 letters that helped shape our view of the Roman Empire

Pliny the Younger helped us shape our view of the Roman Empire, and all aspect of its life.

Pliny the Younger, or more correctly Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, the nephew of Pliny the Elder wrote hundreds of letters, of which just 247 survived. Some were addressed to Emperors and some to notables like the historian Tacitus. Pliny’s letters, the Epistulae cover a wide variety of topics and give us a viewpoint of everyday life and the concerns of the Roman elite.

Who was Pliny the Younger?

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, commonly known as Pliny the Younger, was born in Como in 62 A.D. When he was only eight, his father Caecilius died, and he was adopted by his uncle, Pliny the Elder, the author of Natural History. Pliny the Younger received a thorough education, studying rhetoric under Quintilian and other renowned teachers, becoming the most eloquent advocate of his era.

He modeled himself after Cicero, who was by then regarded as the master of Latin prose. As a young man, he served as a military tribune in Syria but did not seem to have much enthusiasm for military life. Upon his return, he entered politics during Emperor Domitian's rule, and in 100 A.D., he was appointed consul by Trajan, gaining close access to the emperor.

As governor of Bithynia, he regularly consulted Trajan on policy matters, and their correspondence, is highly informative, revealing much about their characters and the issues of their time. Pliny is believed to have died around 113 A.D. Most of his speeches have been lost, except for a panegyric on Trajan, which, despite being overly complimentary by modern standards, became a model for such compositions.

His speeches were typically either forensic or political, many being impeachments of provincial governors for cruelty and extortion, much like Cicero's speeches against Verres. These activities, along with his general public service, show him as a man of integrity and public spirit, and he was also a generous benefactor to his hometown.

Pliny's letters, which are the primary basis for his modern fame, were written with publication in mind and arranged by Pliny himself. Unlike Cicero's more spontaneous letters, Pliny's are considered more deliberate and polished, yet they are highly engaging for modern readers. They cover a wide range of topics: descriptions of a Roman villa, the pleasures of country life, social commentary on literary readings, accounts of dinner parties, legacy-hunting in Rome, acquiring a piece of statuary, his love for his young wife, ghost stories, floating islands, a tame dolphin, and other marvels.

Most notably, his letters describing the eruption of Vesuvius, in which his uncle died, and his correspondence with Trajan about suppressing Christianity in Bithynia, are particularly well-known. Overall, these letters provide a vivid and absorbing picture of the early Roman Empire and the life of a cultured and wealthy Roman gentleman. They occasionally address significant historical events but are most valuable for their portrayal of everyday life in a time not so different from our own. Pliny himself emerges as a fascinating figure, with his vanity, self-importance, sensibility, affection, pedantry, and loyalty. (Letters of Pliny, by Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus. Translated by William Melmoth)

Pliny lived during the peak of the Roman Empire, born in A.D. 62 during Nero's reign in Comum near Lake Como in northern Italy, and he lived until about A.D. 112. His family was not part of the old Roman nobility but belonged to the equites Romani, the second tier of the Roman upper classes. Pliny trained as a civil law advocate and, through his talents and the influence of senatorial family friends, advanced to the senior ranks of the Roman administration.

He became a Roman senator at around twenty-eight years old and eventually reached the highest levels of public service, making him the first senator in his family and a self-made man by Roman standards. Additionally, Pliny was highly educated; he studied under the most renowned literature professors in Rome, particularly the great Quintilian, whose book on rhetoric illustrates the type of education Pliny received.

As a successful lawyer, Pliny played a leading role as chief prosecutor in some of the major political trials of his era, during the peak of the Roman Empire. By the standards of his time, he was an exceptional public orator, both in the law courts and the Roman Senate. As an administrator and friend of emperors, he reached the highest levels of Roman society, serving as consul.

He deeply contemplated the ethics and limitations of absolute political power. He wrote poignantly about his love for his much younger second wife and lamented his lack of children. He provides most of what we know about the literary practices of Roman writers and authors of his time. His writings offer unique insights into the early days of Christianity. Additionally, he witnessed and survived the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. (Pliny the Younger: A Life in Roman Letters. By Rex Winsbury)

The magnificent story of Vesuvius

In his letter to the historian Tacitus, Pliny the younger describes the events that led to his uncle’s death (Pliny the Elder) and he also gives details of the eruption of Vesuvius.

At seventeen years old, he witnessed the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD from his uncle's home in Misenum. He wrote a highly accurate account of the event about 25 years later. Originally intended as letters to the historian Tacitus to describe and perhaps honor the death of his uncle, these letters were rediscovered in the 16th century. They have since become a vital primary source for understanding the different stages of the eruption.

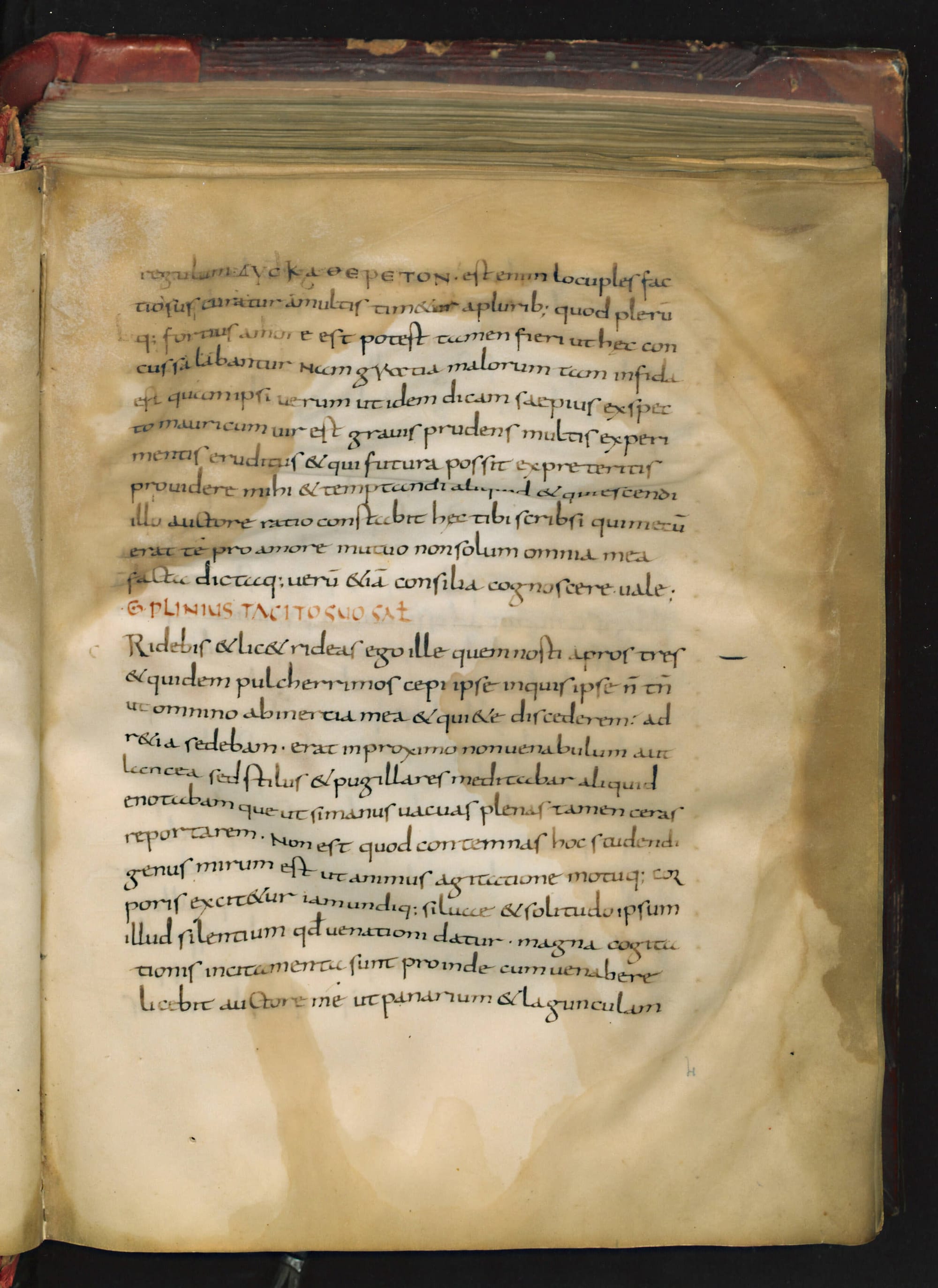

“My dear Tacitus,

You ask me to write you something about the death of my uncle so that the account you transmit to posterity is as reliable as possible. I am grateful to you, for I see that his death will be remembered forever if you treat it [sc. in your Histories]. He perished in a devastation of the loveliest of lands, in a memorable disaster shared by peoples and cities, but this will be a kind of eternal life for him. Although he wrote a great number of enduring works himself, the imperishable nature of your writings will add a great deal to his survival. Happy are they, in my opinion, to whom it is given either to do something worth writing about, or to write something worth reading; most happy, of course, those who do both. With his own books and yours, my uncle will be counted among the latter. It is therefore with great pleasure that I take up, or rather take upon myself the task you have set me.”

Pliny Letter 6.16

Ancient Pompeii was situated on the volcanic plain of Campania in Southern Italy, with Mount Vesuvius looming over the plain, positioned on two fissures in the earth's crust. Pliny described the earth tremors in Campania as frequent or "a common occurrence," indicating that people were neither particularly shocked nor frightened before the eruption, unaware of the connection between seismic and volcanic activity.. The earth tremors, which Pliny noted as growing "much stronger," signaled the increasing seismic activity in Mount Vesuvius, indicating a looming disaster.

“The cloud was rising from a mountain – at such a distance we couldn't tell which, but afterwards learned that it was Vesuvius. I can best describe its shape by likening it to a pine tree. It rose into the sky on a very long "trunk" from which spread some "branches." I imagine it had been raised by a sudden blast, which then weakened, leaving the cloud unsupported so that its own weight caused it to spread sideways. Some of the cloud was white, in other parts there were dark patches of dirt and ash. The sight of it made the scientist in my uncle determined to see it from closer at hand.”

Pliny Letter 6.16

Modern geologists have discovered that the blast from Vesuvius consisted of superheated volcanic gas, ash, and debris ejected from its crater. As the volcanic column cooled, this material was carried by the wind and rained down on Pompeii. The sudden eruption of Vesuvius was caused by a reservoir of magma, approximately 3 kilometers wide, beneath the volcano. This magma was held in place by an old magma plug. The eruption occurred when a chemical reaction between water and gases caused this lava plug to burst, releasing the trapped magma and reactivating Vesuvius.

Pliny’s detailed account of the cloud he observed was crucial in identifying the type of eruption that destroyed Pompeii. His observations were so significant that the eruption type was named after him, known as a Plinian eruption.

The Epistulae

Pliny is mostly known from his letters, a common habit of his class. From 99 to 109 CE, while serving in various government roles, Pliny composed two volumes of verses and wrote nine books comprising 247 literary letters, known as the Epistulae. These letters, often offering advice, were addressed to family and friends and typically carried a strong moral message. They were meticulously composed in a detailed, formal style, and many believe Pliny carefully edited them before publication. The letters included observations on social and domestic matters, as well as contemporary judicial and political events, particularly those concerning the widely despised Emperor Domitian.

There are many questions about Pliny’s letters: are they revised by himself before publishing them? Are there secret meanings between the lines? Was he after immortality, that is did he want to live through history and become famous?

Roman Piso, in his Pliny The Younger: His Words & Phrases, [ Pliny The Younger As The New Testament Paul ] says:

“As we examine Pliny’s letters, we find several items which are predominant throughout them. And one of those being that he appears to have a very high regard for “fame.” Not just the kind of fame that one may have during their lifetime, but (a) “immortal fame.” And one of the means by which he displays his intent to achieve that kind of fame is to be the source of any number of “catch phrases” or cliché’s. He shares this in common, in fact, with Suetonius. Pliny calls these “figures of speech.”

Since in our studies, we have already found out a great deal about the circumstances in which the writers of Pliny’s time were writing,* we then also know much about what HE is really referring to when he says certain things in his literature. This is true of his statement regarding “the favored few.” He is referring to the privilege of the royals to be published, etc., whereas the common people enjoyed no such thing. Though Pliny keeps up the act of pretending to be a typical Roman who worships the Roman gods, he nonetheless makes use of several methods and means of promoting Christianity and various elements of it. This is so, because he, in reality, helped create Christianity by playing the part of “Paul.” And as Pliny, he is secretly promoting it.”

Epistulae is the largest surviving body of Pliny’s work. Pliny's letters are compiled into ten books, nine of which were published during his lifetime, and the tenth posthumously. These letters cover a wide range of topics, including politics, social issues, literary criticism, and daily life in the Roman Empire. Controversial and interesting, they need a lot of research and thinking.

Pliny the Younger’s True Character

Pliny the Younger is a complex historical figure, and opinions about his character vary widely.

Desire for Immortality

Pliny was indeed concerned with his legacy and reputation. His letters were meticulously crafted and edited, suggesting a desire to present himself in a favorable light to posterity. This concern for how he would be remembered indicates a certain level of self-awareness and ambition for lasting recognition.

Manipulation and Reality

Some scholars argue that Pliny's letters might not be entirely candid and could have been shaped to reflect his desired image. By carefully curating his correspondence, he could have manipulated readers' perceptions, presenting a polished and somewhat idealized version of reality.

Role in Christianity

The claim that Pliny invented or promoted Christianity is not supported by historical evidence. However, Pliny's letters to Emperor Trajan provide one of the earliest non-Christian accounts of the treatment of Christians in the Roman Empire. In his role as governor of Bithynia, he sought advice on how to deal with Christians, indicating that he encountered them as a social and legal issue rather than actively promoting or inventing the religion.

When writing to Emperor Trajan, Pliny says:

“It is my practice, my lord [Trajan], to refer to you all matters concerning which I am in doubt...I have never participated in trials of Christians. I therefore do not know what offenses it is the practice to punish or investigate, and to what extent. And I have been not a little hesitant as to whether there should be any distinction on account of age or no difference between the very young and the more mature, whether pardon is to be granted for repentance, or, if a man has once been a Christian….I have interrogated these as to whether they were Christians; those who confessed a second and a third time; threatening them with punishment; those who persisted I ordered executed.”

(Letters 10.96-97)

Manipulative Nature

Some interpretations of Pliny's actions and writings suggest he could be manipulative, using his letters to curry favor, showcase his virtues, and influence opinions. His public persona, characterized by apparent amicality and generosity, may have been a strategic mask to enhance his status and influence.

Public Spirit and Integrity

Despite criticisms, Pliny's public career shows him as a man of integrity and public spirit. His efforts to prosecute corrupt officials and his contributions to his hometown indicate a commitment to justice and civic duty.

Personal Relationships

Pliny's letters often reveal deep affection for his friends and family, and his grief over the loss of his wife and children appears genuine. Whether these emotions were exaggerated for effect or sincerely felt is a matter of debate.

Literary and Cultural Contributions

Pliny was a highly educated man and a patron of the arts. His works provide valuable insights into Roman Empire life and thought, even if they are sometimes seen as self-serving or idealized.

In summary, Pliny the Younger was a multifaceted figure who sought to secure his legacy through careful self-presentation. While some view him as manipulative and self-promoting, his contributions to literature and his public service reflect a man deeply engaged with the cultural and political life of his time.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: