Numidia: Rome’s African Frontier and the Soldiers Who Changed an Empire

Bareback across the North African plains, Numidian horsemen changed the course of Roman warfare—while their highland homeland defied conquest for centuries. From Masinissa’s cavalry to the Aurès frontier, Numidia helped shape Rome’s military and imperial legacy.

They rode without saddles, bareback across the North African plains—swift, elusive, and deadly. These were the horsemen of Numidia, masters of the desert and unexpected architects of Roman victory and defeat.

From Masinissa’s alliance with Scipio Africanus during the Punic Wars to Jugurtha’s ruthless guerrilla tactics that exposed the rot at the heart of the Roman Senate, Numidia played a role far larger than its borders suggested. It was not merely a client kingdom or a rebellious province—it was a crucible in which the ambitions, contradictions, and vulnerabilities of the Roman Republic were laid bare.

The Rise of Numidia and Its Role in Rome’s Wars

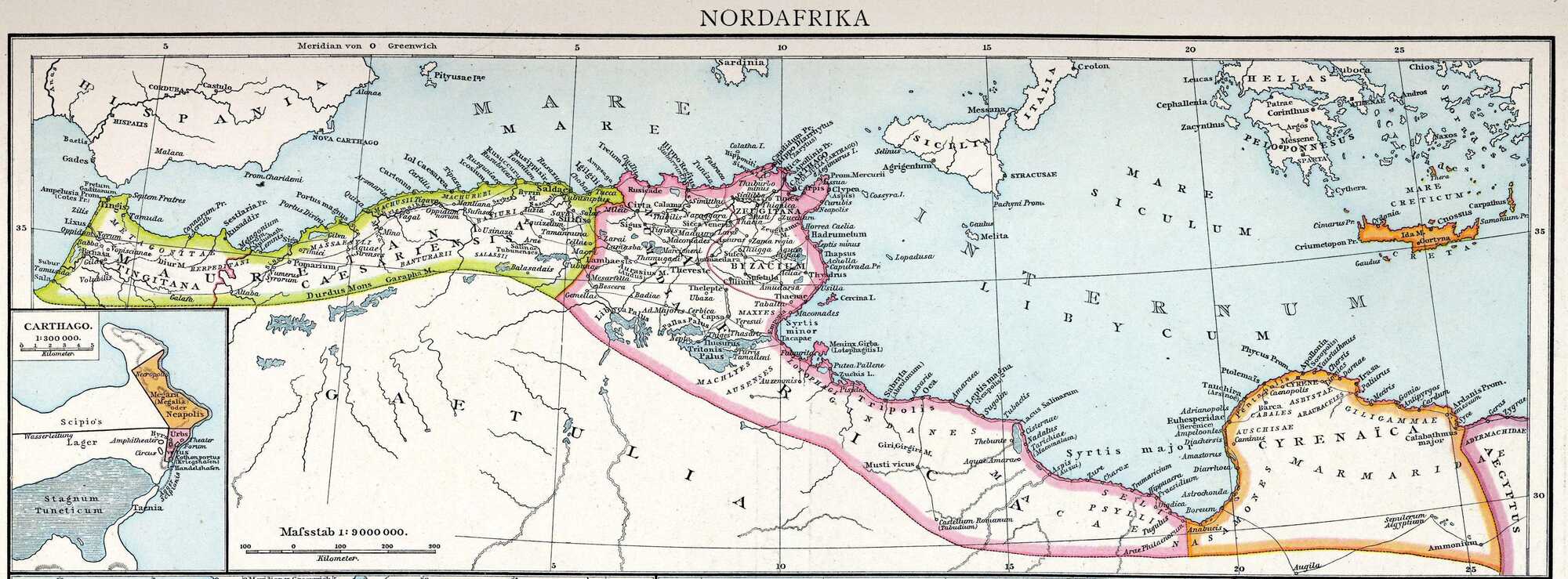

The Numidians were a tribal, largely nomadic people who inhabited the lands of North Africa corresponding to modern northern Algeria and western Tunisia during the final centuries BCE. To their east lay the Carthaginian hinterland, while to the west stretched the territory of the Mauri, a closely related nomadic group. On the southern fringe, bordering the desert, were the little-understood Gaetulians.

Though largely absent from earlier Greek and Roman records, Numidia first entered the historical spotlight during the First Punic War (264–241 BCE), when Polybius briefly mentioned their cavalry. By the start of the Second Punic War in 218 BCE, formerly independent Numidian tribes had coalesced into two rival kingdoms.

In the east, the Massyli, ruled by King Gaia, held sway from their capital at Cirta (modern Constantine). To the west, the more powerful Masaesyli were led by King Syphax, who ruled from Siga (near present-day Oran).

Both kingdoms supplied their famed light cavalry to Rome and Carthage at different times, and both shifted allegiances during the conflict. Rome, eager to win Numidian favor, supported Syphax with military training. Nevertheless, by 204 BCE, Syphax had aligned himself with Carthage, strengthening the alliance through marriage to Sophonisba, daughter of the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal.

Gaia’s Massyli had initially supported Carthage as well, and his son Masinissa even led cavalry against Rome in Spain. After Gaia’s death in 206 BCE, Masinissa fought a series of internal battles to claim his father's throne. Though initially defeated by Syphax and forced to retreat to the mountains, Masinissa regrouped, led a guerrilla campaign, and eventually joined forces with Scipio Africanus and the Romans.

He proved crucial in Rome’s African campaign. His cavalry helped destroy a joint Carthaginian–Numidian camp by fire, inflicting heavy losses. In 203 BCE, alongside Roman forces, he captured Syphax at the Battle of Cirta and swiftly took the city.

According to Livy, Masinissa fell in love with Syphax’s wife, Sophonisba, and tried to marry her to spare her humiliation in Rome. When Scipio refused the union, he gave her poison to preserve her dignity, and she died in his arms.

With Roman backing, he consolidated power over both the Massyli and Masaesyli territories. Following Scipio’s triumph over Hannibal at Zama in 202 BCE, he emerged as Rome’s favored king in North Africa. His reign marked the birth of a unified Numidia under strong Roman patronage—a bulwark against any Carthaginian resurgence.

Numidia flourished under Masinissa and his son Micipsa. While nomadic life endured, agriculture expanded, towns grew, and trade flowed through ports once controlled by Carthage. The Numidian kings earned Rome’s loyalty by providing grain and elite auxiliaries—light cavalry, infantry, and even war elephants—for the Roman legions.

They also adopted aspects of Hellenistic culture: their coin portraits bore the royal diadem, and Greek-style architecture adorned their cities.

Coin depicting Masinissa, the first king of Numidia. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

One of Masinissa’s sons even competed in the Panathenaic Games in Athens. Upon Micipsa’s death in 118 BCE, Numidia was divided among his two sons, Hiempsal and Adherbal, and his nephew Jugurtha, a veteran of Rome’s Spanish campaigns. Jugurtha, ambitious and ruthless, assassinated Hiempsal and later executed Adherbal despite Roman attempts to broker peace. Rome declared war in 111 BCE, and after years of difficult fighting, finally captured Jugurtha in 106 BCE.

Though a period of stability followed, Numidia’s independence came to an end during the civil wars of the late Republic. King Juba I sided with Pompey against Julius Caesar, and after his defeat at the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BCE, Numidia was dismantled. Juba’s suicide marked the end of the kingdom. Most of Numidia was absorbed into the Roman Empire, becoming a new chapter in Rome’s African dominion.

The Numidian Cavalry and Their Lasting Legacy in Roman Warfare

The Numidian cavalry were among the most skilled and recognizable horsemen of the ancient world. Famed for their unmatched agility and precision, they rode without saddles or bridles, defended only by hide shields, and carried light javelins for rapid, harassing attacks.

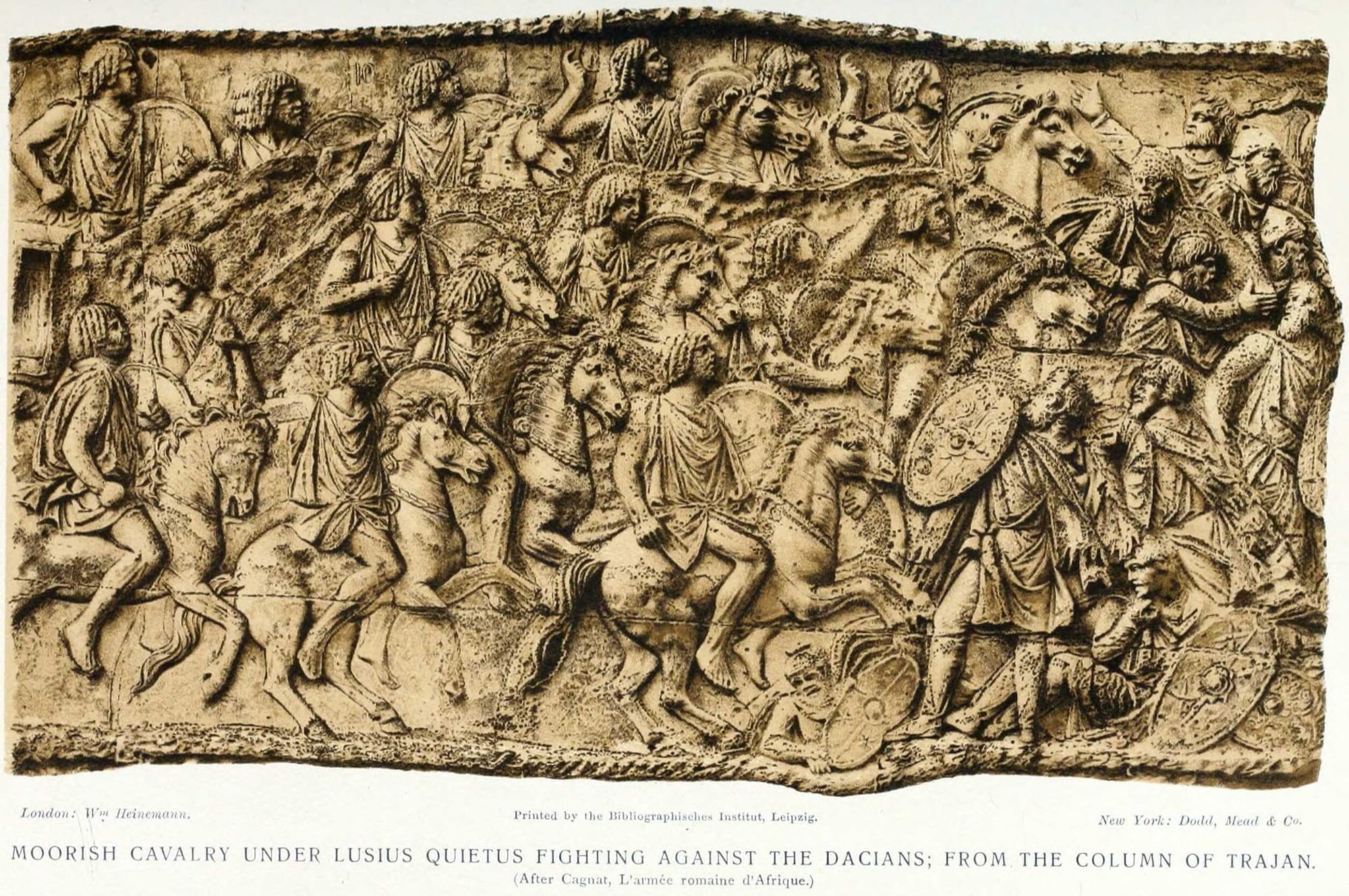

These barefoot riders, clad in simple tunics and astride small, resilient horses, became iconic thanks to their vivid depiction on Trajan’s Column—“dreadlocked” and lightly armed, their image would define how Numidians were remembered.

Yet this common portrayal oversimplifies a more diverse and tactically sophisticated military tradition. Numidian forces also included infantry, missile troops like archers and slingers, elephants, and possibly even elite units of armored cavalry wielding ornate shields. A close analysis of literary and archaeological evidence reveals that the military apparatus of Numidia was far more complex than the narrow focus on cavalry might suggest.

The Numidian cavalry, despite their rudimentary equipment, played a vital role in both Carthaginian and Roman military operations. Their horses—small, hardy, and adapted to long desert campaigns—formed the very foundation of Numidian power. Their contribution of expert riders became a strategic currency: Rome and Carthage both vied for Numidian alliances not only for diplomatic advantage, but to gain access to these exceptional troops.

Numidian boys learned to ride from an early age, often spending much of their youth mastering equestrian skills while hunting. According to Strabo, the reins consisted of a single line attached to a simple collar made from fiber or hair. Riders guided the horses with gentle touches of a rod, developing such strong bonds that:

“Some would even follow their master around like a dog.”

Livy reported that seasoned horsemen brought spare mounts into battle and could leap between them mid-fight to stay ahead of fatigue:

"Not all the Numidian horse, however, were on the right wing, but only those who were trained to manage two horses at the same time like circus-riders and, when the battle was at the hottest, were in the habit of jumping off the wearied horse on to the fresh one, such were the agility of the riders and the docility of the horses."

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, (History of Rome) Book 23, Chapter 29

The horses themselves were fast, enduring, and unpretentious. Aelian praised their stamina, noting that they thrived on grass and rarely required water—ideal traits for military service:

"Now the horses of the Numidians, a Libyan tribe, are small and not very good looking, but exceedingly swift and hard to tire; they are content with very little food and do not drink much."

Aelian, On the Nature of Animals, 3.2

He also observed their minimal upkeep:

“They were never washed or groomed, their hooves were never cleaned and their manes and tails were left unbrushed.”

Livy described their appearance as “awkward, ungraceful,” with stiff necks and heads stretched forward—a depiction echoed in coinage of King Syphax and terracotta figurines from Canosa.

"...the horses without bridles, their very motion being the ugly gait of animals running with stiff necks and outstretched heads"

Livy, The History of Rome, Book 35

Sculptors of Trajan’s Column appear to have deliberately emphasized the differences between Numidian and Roman cavalry horses. Scholars Dixon and Southern noted their “distinct head shape, long necks and manes” contrasted with the Roman horses’ “heavier bodies and more slender legs.”

Tactically, the Numidian cavalry were not shock troops but skirmishers of rare finesse. As Polybius recounts, they harassed enemy lines with precision. At the Battle of the Trebbia (218 BCE), their:

“repeated attacks followed by swift, scattering retreats,”

disrupted Roman formations.

At Cannae, they prevented Roman cavalry from reaching the center of battle. Their javelins could strike from close range, but their lack of armor—entirely by design—ensured maximum mobility. They were almost impossible to trap in melee—combat fought at close range, often chaotic and without formation.

These tactics originated in North African tribal warfare, where fast raids with minimal casualties protected the adult male population. Over time, they became formalized military doctrine—so effective that Carthaginian generals, observing Numidian raids, recruited them extensively.

Hannibal relied heavily on them during the Second Punic War, where they performed reconnaissance, burned crops, and denied Romans vital supplies. But their numbers dwindled over time. In 210 BCE, Hannibal lost 500 Numidian riders at Salapia, a devastating blow. Livy noted that this loss cost Hannibal his cavalry superiority—more than the loss of the city itself. By Zama (202 BCE), Scipio had the advantage: he allied with King Masinissa, whose superior cavalry helped defeat Hannibal and end the war.

In the aftermath, Masinissa solidified his power and supplied Rome with cavalry and elephants in exchange for political support. Numidian units served Rome across the empire: 200 fought in Greece during the Second Macedonian War, more under Masinissa’s son Misagenes in the Third, and others in Gaul, Liguria, and Spain.

Their tactics proved life-saving in several Roman campaigns. In 193 BCE, trapped by Ligurians in a narrow valley, the consul Quintus Minucius sent Numidians ahead. Pretending to fall off their horses and play games, they lulled the enemy into relaxing, then broke through the lines and torched farms, forcing the Ligurians to retreat (Frontinus 1.5.16).

"When the army of the consul Quintus Minucius had marched down into a defile of Liguria, and the memory of the disaster of the Caudine Forks occurred to the minds of all, Minucius ordered the Numidian auxiliaries, who seemed of small account because of their own wild appearance and the ungainliness of their steeds, to ride up to the mouth of the defile which the enemy held.

The enemy were at first on the alert against attack, and threw out patrols.

But when the Numidians, in order to inspire still more contempt for themselves, purposely affected to fall from their horses and to engage in ridiculous antics, the barbarians, breaking ranks at the novel sight, gave themselves up completely to the enjoyment of the show.

When the Numidians noticed this, they gradually grew nearer, and putting spurs to their horses, dashed through the lightly held line of the enemy.

Then they set fire to the fields near by, so that it became necessary for the Ligurians to withdraw to defend their own territory, thereby releasing the Romans shut up at the pass."

Frontinus, Strategemata Book I, Chapter 5, Stratagem 16 (1.5.16)

A similar feat occurred in Thrace in 190 BCE, where Muttines and 400 cavalry, aided by elephants and a flanking maneuver from his son, routed 15,000 Thracians (Livy 38.41), protecting the Roman column.

Even after Numidia was annexed in 46 BCE, Rome continued recruiting from the region. These light cavalrymen helped patrol African frontiers and supported imperial campaigns. Their gear, techniques, and tactical philosophy remained strikingly consistent from the days of Hannibal to the imperial legions centuries later. (The Numidians 300 BC–AD 300, by William Horsted)

While Numidian cavalry left their mark on battlefields across the empire, the Roman army faced a far more difficult challenge within Numidia itself. In the rugged highlands of the Aurès Mountains, Rome encountered not just military opposition—but an enduring spirit of resistance rooted in the land.

Southern Numidia and the Roman War Machine: Rebellion, Fortresses, and the Frontier in the Aurès Mountains

The southern region of ancient Numidia, dominated by the vast and rugged Aurès Mountains, held a unique and enduring position in the history of Roman North Africa. This highland terrain became a long-standing zone of conflict, known for its fierce resistance to Roman control.

Even at the height of its imperial strength, Rome never fully subdued the Berber tribes of the region—particularly the Chaouia people—who made the Aurès a stronghold of rebellion. Despite this defiance, the region also hosted some of the most concentrated Roman military and urban development in Mauretania. Cities like Lambèse (Lambaesis), Zana (Diana Veteranorum), and Al-Kantara (Calceus Heraculis) emerged alongside major military installations.

These settlements often grew from military roots, many founded by veterans of the Roman legions—particularly those from the Third Augustan Legion (Legio III Augusta). Important cities such as Timgad (Thamugadi), Khanchela (Mascula), and Markouna (Verecunda) stand as monuments to this process of military-led urbanization.

A collection of Roman monuments in Numidia. Credits: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0

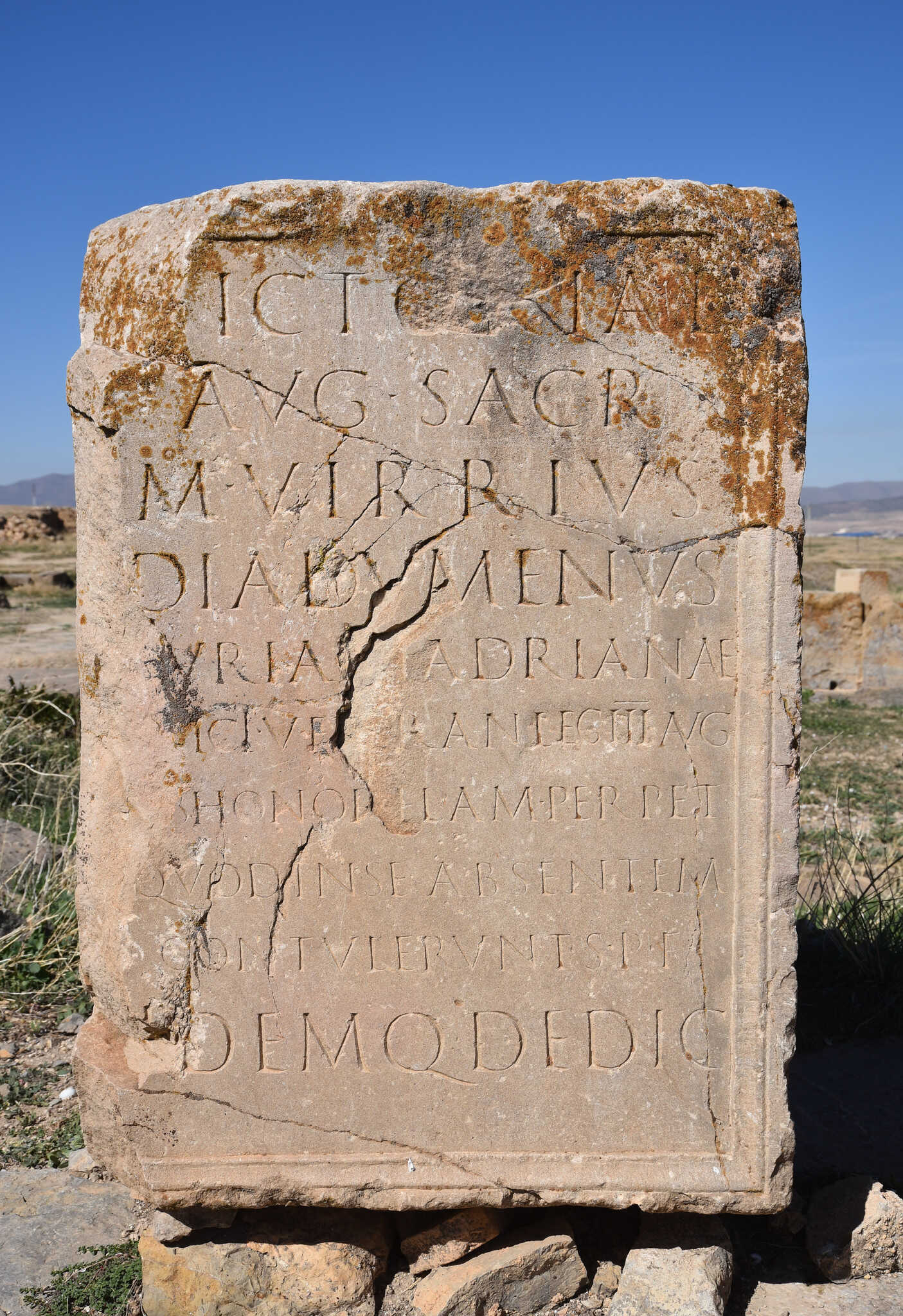

Photo #2: Inscription from Lambaesis (Numidia) dedicated to Victoria Augusta, AE 1916 0022, Marcus Virrius Diadumenus, veteran of the Third Legion Augusta, erected a statue to Victory using his own money Lambaesis (Numidia), Algeria

Photo #3: The Cardo Maximus (north–south-oriented street), looking towards the North Gate, Thamugadi (Timgad), Numidia, Algeria

Photo #4: The Theatre, cut into the side of a natural hillock, it had a capacity of 3,500-4,000 spectators, Thamugadi (Timgad), Numidia, Algeria

Photo #5: The Groma at the centre of the Hadrianic legionary base of the Legio III Augusta, founded shortly before Hadrian's visit in AD 128, Lambaesis (Numidia), Algeria

Modern historians often refer to this heavily fortified and militarized region as “Southern Numidia,” or metaphorically, “Numidia Militiana”—a term rooted in the presence of the Roman legions rather than any formal provincial designation. This term appears only once in ancient records (on the Verona List, early 4th century CE), and was never a recognized administrative unit under the High Empire (27 BCE – 284 CE).

Instead, it reflects the dense concentration of Roman military activity, particularly around the Legio III Augusta, which was headquartered at Lambaesis for over 300 years. Geographically, “Southern Numidia” extended from Theveste (modern Tebessa) in the east to the frontier area near Zarai (modern Zraya) and Kherbet al-Maghder (ancient Perdices) in the west.

This corridor also marked the fluctuating boundary between Numidia and Mauretania Caesariensis. The exact dividing line between the civilian and military-controlled zones is difficult to reconstruct, but military centers were typically located along the key Roman road that ran from Theveste to Lambaesis and northwest toward Zarai. South of this axis, Roman control was clearly exercised through military authority rather than civilian governance.

The Roman presence in Southern Numidia evolved out of necessity and imperial ambition. After Julius Caesar’s victory at Thapsus in 46 BCE and the defeat of King Juba I, Rome began pushing southward to secure its African territories from the hostile Berber tribes in the Saharan Atlas and desert margins.

Augustus, as Octavian, began integrating Africa Nova with Africa Vetus and established an expansive network of roads. This triggered localized resistance, notably by the Gaetuli tribes in the Aurès and western frontier zones, leading to imperial military intervention in 21–22 BCE.

Renewed resistance arose during the reign of Tiberius. A Berber leader named Tacfarinas, of the Musulamii tribe, launched a sustained revolt in the early 1st century CE. Roman expansion into the Aurès intensified in response, with Rome aiming to pacify the region and incorporate it into a structured frontier. Many Musulamii were eventually settled and conscripted into Roman service, forming auxiliary units such as the Cohors I Flavia Musulamiorum.

At this time, during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius, the boundaries between Numidia and Gaetulia remained vague.

Detail from a map of Africa, mid 19th century. Credits: Fondo Antiguo de la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Sevilla

“Gaetulia” itself lacked definition as a political unit and was used more generally to refer to southern territories beyond Tebessa. Over time, the Roman limes (frontier defense line) in the Aurès expanded, stretching east to the mountainous Nememcha block and westward into Belzma and Boutaleb. This frontier infrastructure would become known as the Aurès Limes Line.

By the late 1st century CE, under the Flavian emperors, a second phase of military consolidation began. Roman forces moved from Ammaedara to Theveste (AD 75–79), transforming it into a military base for further expansion into the western and southern Aurès. Emperor Titus established a permanent camp for Legio III Augusta at Lambaesis in AD 81, anchoring the limes line.

Under the emperors Trajan and Hadrian, this limes was pushed deeper into the semi-desert regions south of the Aurès. Forts and garrisons were established across a string of critical outposts, including:

- Henchir Besseriani (Ad Maiores)

- Tadart (Ad Medias)

- Bades (Badias)

- Tahouda (Thabudeos)

- Henchir al-Kasbat (Gemellae)

- Tobna (Tubunae), on the edge of the Hodna region

The final and third phase of Rome’s southern expansion came during the Severan dynasty. The limes system reached its greatest extent, incorporating military installations in the Ziban region (southwest of Biskra/Vescera) and al-Hodna. These zones served both as surveillance points to monitor Saharan nomadic movement and as agricultural zones to supply Roman outposts.

This frontier system was hierarchical and well-organized. It comprised permanent camps, forts, and smaller watchtowers operated by either the Legio III Augusta or auxiliary cohorts, all under central command based in Lambaesis.

Roman patrols traversed strategic routes, controlling access to pasturelands and preventing nomadic incursions. The agricultural productivity of these fortified zones supported trade and communication between military and civilian settlements, ensuring Rome’s grip on this volatile but vital frontier.

The Roman provinces of Africa left their mark in modern Tunisia. Detail from a Roman mosaic, a Roman bath, and the Temple of Minerva. Credits: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0

Conquest, Colonization, and Romanization

The Roman army served as the primary force behind the empire’s relentless expansion—and North Africa was no exception. In this vast region stretching from the Mediterranean coast to the outer reaches of the Sahara, military power was the key to imposing Roman control. Alongside the Africa Proconsularis, Numidia emerged as one of the most prosperous and urbanized provinces in Roman North Africa.

To ensure security and lasting peace—not only within Numidia but also in its neighboring provinces—the Roman military established a carefully designed defensive system, with fortifications deployed along the southern frontier of the province. This network extended across the northern, southern, and western flanks of the Aurès Mountains, forming a barrier against incursions and a backbone for Roman dominance.

Yet the army’s contribution in Numidia went far beyond warfare. Roman forces played a direct role in implementing the Romanization of the province, orchestrating the layout of the land, and overseeing the construction of infrastructure—towns, roads, bridges, aqueducts, and other hallmarks of Roman civic life. These initiatives laid the groundwork for both Roman colonization and the integration of local communities.

Veterans who completed their service were often granted land in the region, where they settled with families that frequently included local women. These mixed households helped knit Roman and Numidian societies together, creating a durable thread of cultural cohesion. While the indigenous population gradually absorbed aspects of Roman civilization, Roman veterans rooted themselves in the African landscape.

Through this dual mission of conquest and construction, the Roman army left a permanent imprint on Numidia, reshaping its geography, society, and identity—traces of which remain visible throughout the Aurès and beyond. (The Roman Presence in Southern Numidia, by Mohamed lakhdar Oulmi, University of Guelma)

Numidia's story is one of paradox—of fierce warriors who became Rome’s most prized auxiliaries, and of mountain tribes who resisted even the might of the legions. From cavalry raids to frontier fortresses, the Numidians left their mark not only on Roman military strategy but on the very shape of empire in North Africa.

The Romanization of Numidia may have transformed its cities and roads, but the land itself—harsh, proud, and untamed in places—remained unmistakably Numidian. In this meeting point of empire and resistance, the legacy of Rome was carved into stone, but the spirit of Numidia endured.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: