Maximinus Thrax: How did a Barbarian Giant, Become Roman Emperor?

Maximinus Thrax, also known as Maximinus I, was a Roman emperor who reigned from 235 to 238 CE, marking the beginning of the Crisis of the Third Century.

Known as Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus, he was of humble origins, hailing from Thrace (hence his nickname "Thrax")—a region roughly equivalent to modern-day Bulgaria and parts of Turkey. His rise to power is significant because he was the first emperor who came from a non-senatorial family and had a background in the military rather than Roman aristocracy.

Maximinus Thrax was known for his massive physical stature, which was widely noted by ancient historians. Described as a giant of a man and the tallest of Roman Emperors, he was said to have extraordinary strength, which helped him gain prominence in the Roman military. He began his career as a soldier and quickly rose through the ranks due to his prowess on the battlefield.

Maximinus, the Thracian

In 194 CE, amid a civil war between Lucius Septimius Severus and Caius Pescennius Niger, Severus’ army camped near Perinthus in Thrace. Severus was recognized as the legitimate emperor by the Roman Senate, while Niger controlled much of the eastern provinces, including vital Egypt.

As the campaigning season approached, Severus organized military games in honor of his son Geta's birthday on March 7th, featuring contests in wrestling and other martial arts. Soldiers competed for medals in what resembled a medieval-style tournament.

A remarkable event unfolded when a massive Thracian man, seeking to join the Roman army, impressed the crowd with his extraordinary physical strength.

A possible representation of the fight between young Maximinus and the Roman soldiers. Illustration: Midjourney

Known for pulling wagons, tearing saplings, and smashing rocks, this man soon stood out. Despite not being allowed to compete in the games as a civilian, he approached Severus and requested the chance to wrestle. Severus, intrigued but cautious about the potential humiliation for officers, allowed the Thracian to challenge common soldiers. He bested 16 men in wrestling, earning rewards and entry into the Roman army.

The next day, the Thracian drew Severus’ attention again by displaying more feats of endurance and strength, including wrestling seven additional challengers. Impressed, Severus awarded him a gold collar and designated him for his personal bodyguard. The Thracian’s fame grew, with people comparing him to legendary figures like Milo of Croton and Hercules.

Though initially known by his Thracian name, he adopted the Roman name Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus. This extraordinary man, later known as Maximinus Thrax, eventually ascended to the throne of Rome, becoming emperor and playing a significant role in the empire's turbulent history.

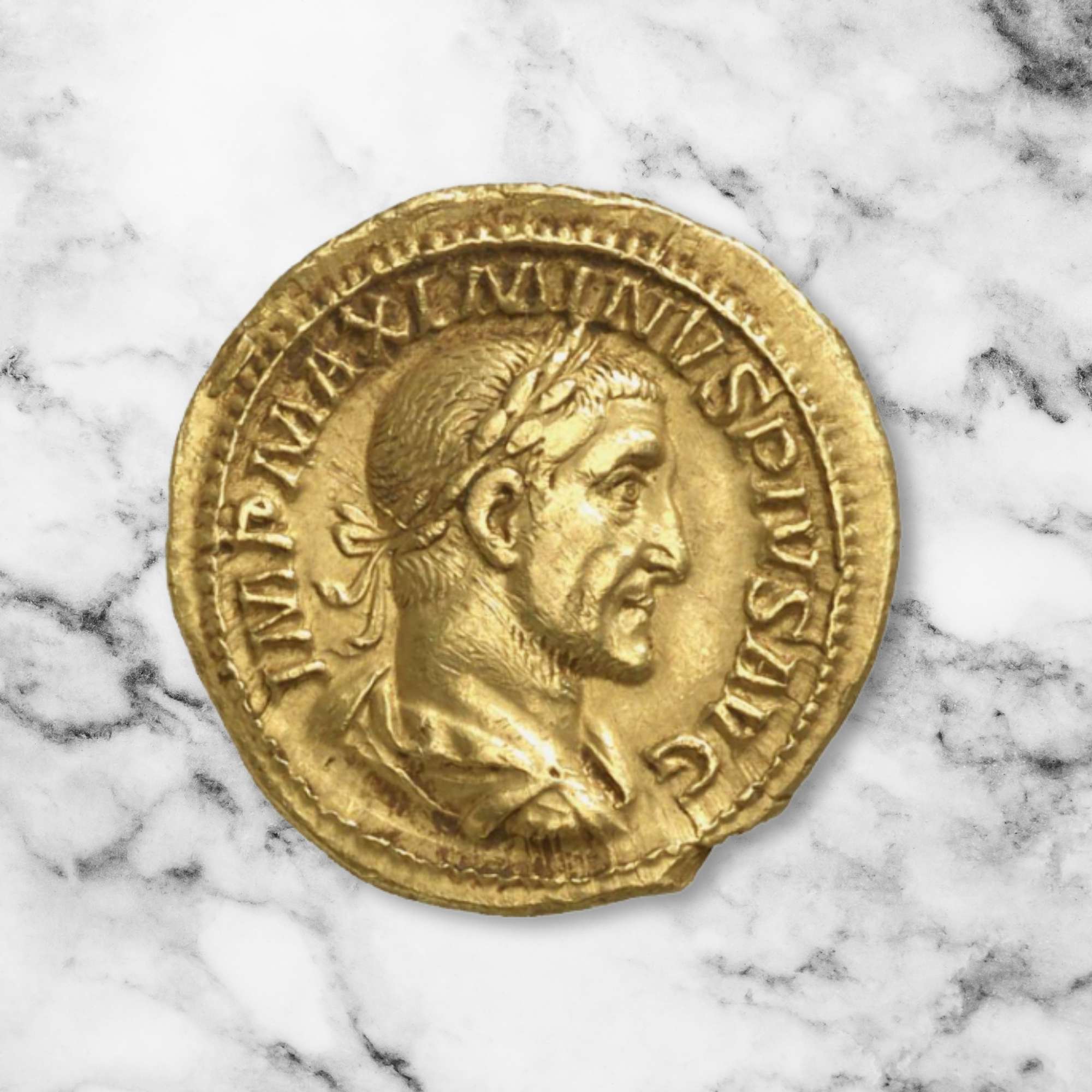

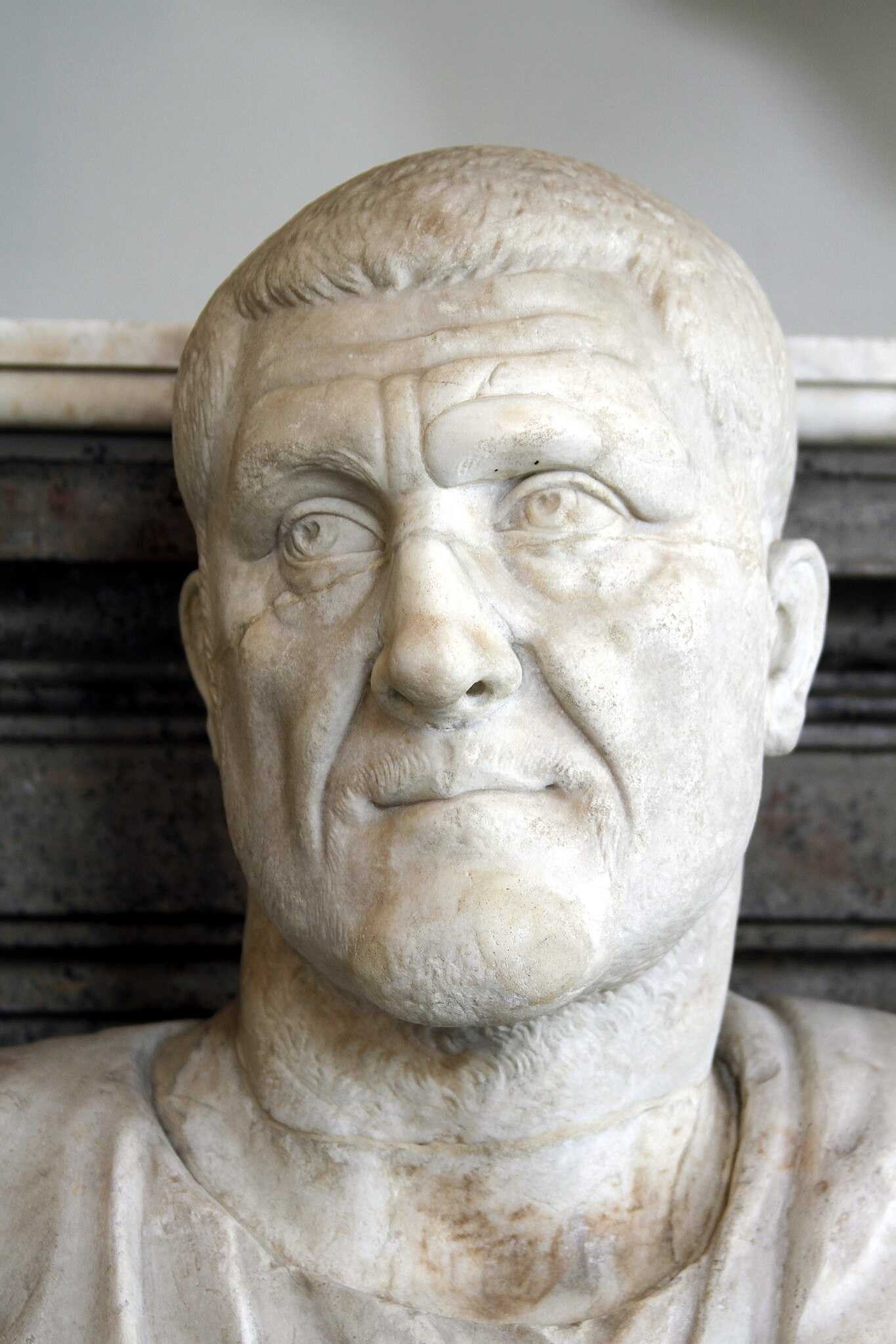

Maximinus was indeed a towering figure, with ancient historians like Herodian describing him as having a "frightening appearance and colossal size" that dwarfed both the best-trained Greek athletes and elite barbarian warriors. Coins, inscriptions, and statues from his era back up this impression. These artifacts show a powerful man with a heavy brow, prominent nose, and sharp gaze—very different from the typical depictions of Roman emperors, who were often balding or corpulent.

Some scholars, like neurologist Harold Klawans, have suggested that Maximinus may have suffered from acromegaly, a condition caused by an excess of growth hormone. This results in enlarged bones and muscles, typically becoming apparent after puberty. If left untreated, it can lead to gigantism. Acromegaly fits well with the physical characteristics described in the sources, providing a plausible explanation for both his imposing appearance and the powerful image reflected in Roman coinage and statues.

Herodian’s History of the Empire from the Death of Marcus Aurelius, a comprehensive Greek narrative, remains one of the most detailed sources on Maximinus’ life and reign. Other valuable works, such as Cassius Dio's Roman History, although only partially surviving, offer critical insights into the early stages of Maximinus' career. These combined sources give us a fuller picture of the man whose physical presence matched his historical impact.

The Roots of a 2.6 meters (8.5 feet) Tower

None of the earlier historical sources provide a clear date for Maximinus' birth. However, the late ancient writer Zonoras suggests it occurred around 172 or 173 CE, which aligns with other known details about his life.

Herodian notes that Maximinus hailed from one of the "semi-barbarous tribes" deep within Thrace, where he spent his youth as a shepherd in a small rural village. This background, from a humble and somewhat isolated community, adds to the narrative of his remarkable rise to power. The Augustan History gives more details:

“He was born in a village in Thrace bordering on the barbarians, indeed of a barbarian father and mother, the one, men say, being of the Goths, the other of the Alans.

At any rate, they say that his father’s name was Micca, his mother Ababa.

And in his early years Maximinus himself freely disclosed these names; later, however, when he came to the throne, he had them concealed, lest it should seem that the emperor on both sides was sprung of barbarian stock.”

It is also mentioned that during his youth, Maximinus led a band of robbers, adding a vivid and dramatic element to his early life. This detail helps paint a picture of his rough and adventurous background before his rise to prominence.

Thracian civilization dates back to ancient times, with discoveries such as the oldest worked gold found in their royal tombs, predating even the famous gold of the Egyptian pharaohs. However, the Greeks viewed the Thracians as the original "barbarians," a term that may refer to their bearded appearance.

This negative perception persisted into Roman times. The Romans had a long and tumultuous history with Thrace, engaging in wars as early as the fourth century BCE, often with mixed success. One legacy of this conflict was the figure of the "Thrax" gladiator, a fierce combatant in the Roman arenas armed with a curved sword and a small shield, frequently matched against more heavily armored opponents.

Not all gladiators who played the role of the "Thrax" were Thracians, but one notable exception was Spartacus, a real Thracian who led a massive slave revolt from 73–71 BCE. This revolt, which came close to threatening Rome itself, further cemented the Roman stereotype of the Thracian as a brutish, strong warrior. The enduring image of the Thracian as a rough and violent figure even extended into modern times.

Herodian mentions that Maximinus came from a mountainous region, an area that had long been controlled by outlaws. These upland districts in Thrace were typically left unpacified due to the expense and difficulty of maintaining control, although occasionally, the Roman military would intervene, particularly when in need of recruits.

Such recruitment efforts were dangerous but necessary. Evidence of these efforts can be found on a marble column at the Asklepios sanctuary near modern Baktun, Bulgaria. The inscription, from a man named Aurelius Dionysodorus, offers thanks for divine assistance in gathering brigands for the army, dating to the late second or early third centuries—possibly linked to Severus’s campaign against Niger.

Thrax’s Distinct Features

As Herodian eloquently describes, Maximinus Thrax was six inches over eight feet in height, towering even a modern NBA center guard, at an astonishing ±2.6 meters height. Apart from the gigantic proportions, he was also described to have great piercing eyes, and his skin was in whiteness pre-eminent among all, contrary to modern representations that portray him as a man of a darker complexion.

His size was so astonishing for the times, that Cordus reports an anecdote about Maximinus‘ thumb, which was so huge he could use his wife’s bracelet for a ring. This, combined with stories that he could punch horses and loosen their teeth, or by striking them with his heel would break their legs, better illustrate why he was called Hercules, or Antaeus.

One of the most fascinating facts has to do with his consumption of food and wine; Maximinus was said to drink often in a single day a Capitoline amphora of wine, an incredible amount of 26.2 litres (or 6⅞ gals.), and to eat no less than sixty pounds (±27 kg) of meat every day! Herodian notes that it seems logical Maximinus did not eat vegetables at all, or anything cold, save for his drinks. The last similar anecdote concerns his sweat, which he would often catch and put in small jars or cups, and afterwards exhibit by this means two or three pints of it.

Maximinus in the Army

Maximinus rose from humble beginnings to hold a senior position in the Roman army, despite not being a citizen, which limited his public office opportunities to military roles. According to the Augustan History, after being chosen for the imperial bodyguard during the civil war against Niger, Maximinus underwent rigorous training under Roman discipline, likely starting his career in the local auxiliary forces, as Herodian noted.

Roman military recruits had to pass strict physical requirements, ensuring they were fit for the demanding life in the legions. Vegetius, a military writer, described the ideal recruit as having a muscular build and strong physical attributes.

Maximinus, with his impressive size and strength, would have easily passed these examinations.

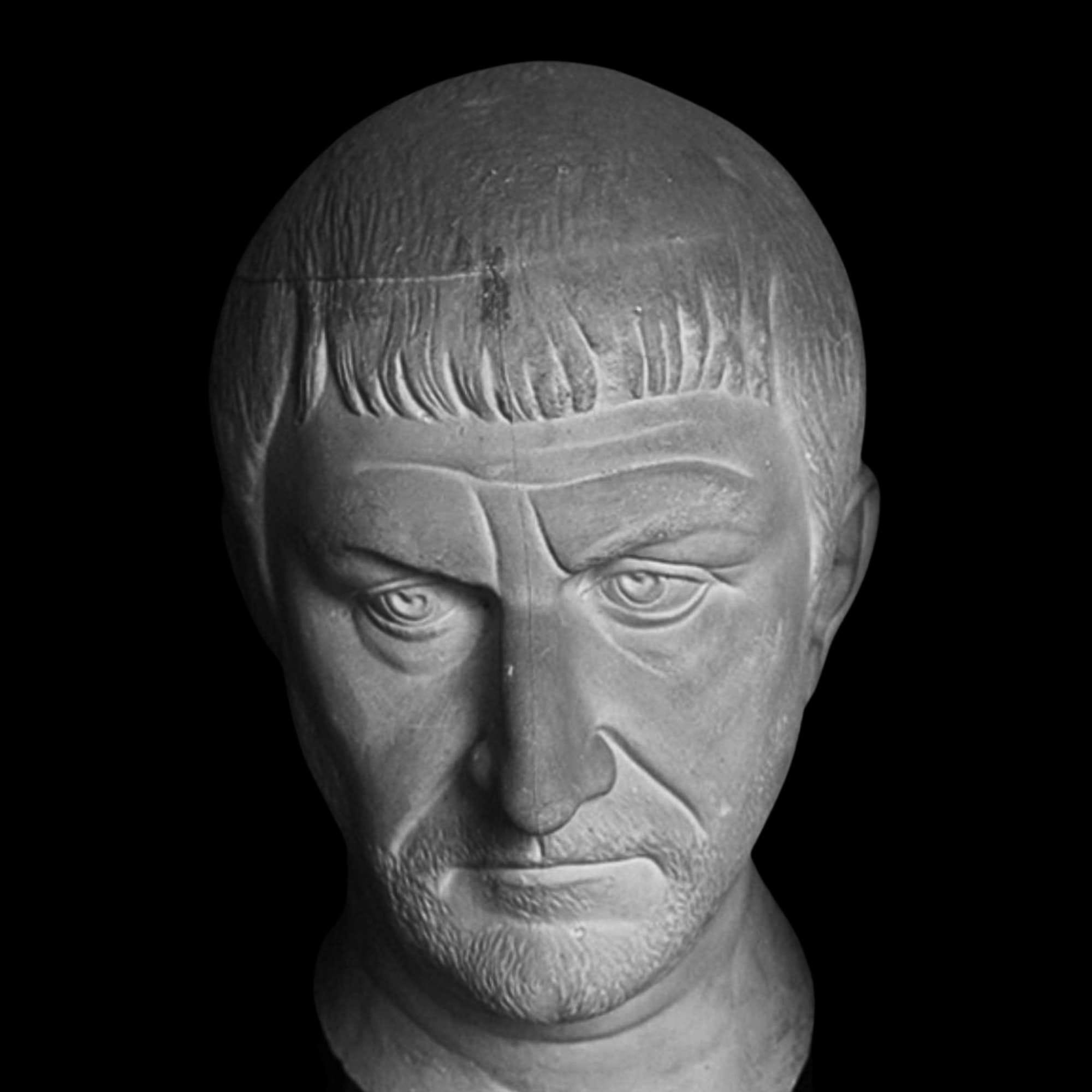

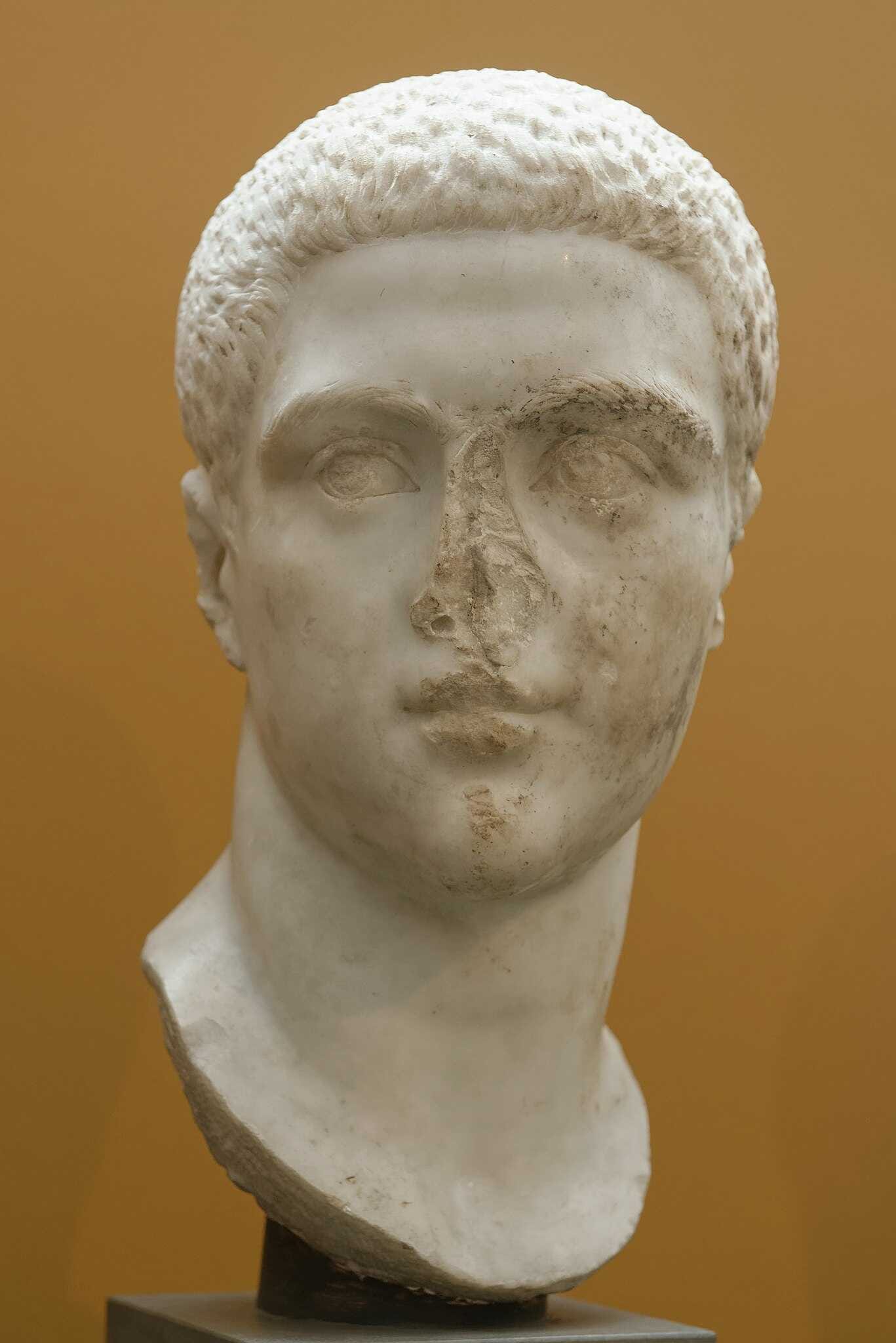

A possible bust of Maximinus Thrax. Credits: National Gallery of Denmark (SMK), CC0 1.0

His training would have involved marching long distances, building fortified camps, swimming across rivers, and mastering a wide array of weapons. Additionally, recruits had to maintain their equipment in excellent condition, further emphasizing the discipline and order of the Roman military. Upon joining, provincial recruits often adopted Roman names, and Maximinus took the name Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus. His impressive physicality likely led him to the cavalry, which was reserved for taller, stronger soldiers and offered higher pay and prestige.

It's probable he initially served in an auxiliary cavalry unit, which was a smaller, versatile force used for both battle and garrison duties. During this time, Maximinus would have learned not only military tactics but also the inner workings of the Roman army, including its superstitions, tricks, and what motivated the men. This experience was crucial for his later career as a commander, as he built the foundation for his rise in the Roman military hierarchy.

After completing his training, Maximinus was assigned to the imperial palace in Rome, where he served as part of the emperor's personal bodyguard (stipatores corporis). It was common for emperors to select physically imposing men for these elite roles. Historical examples include Emperor Caligula's use of Thracian gladiators and Nero’s reliance on a large guard for protection. Under Severus, the imperial horse guard (equites singulares Augusti), which Maximinus likely joined, doubled in size to 2,000 men, favoring recruits from the Danubian provinces.

The barracks of these elite horsemen were located on the Caelian Hill in Rome, close to the imperial palace. These soldiers were taller than most of their contemporaries and were selected not only for their physical ability but also for their appearance. Like many modern ceremonial guards, they performed both elite combat duties and ceremonial roles, often training with a wide array of weapons like javelins and slings.

In peacetime, they engaged in public displays of martial skill, always immaculately turned out with gleaming armor and richly embroidered capes. Maximinus, who was renowned for his size and strength, would have been a prominent figure in these displays. He quickly became well-known and admired by his fellow soldiers, gaining favor with both his comrades and commanding officers.

Posting to the imperial horseguard was a prestigious assignment throughout the Roman Empire, and many elite soldiers aspired to it. Promotion within the guard was notably rapid, with recruits quickly rising through the ranks. After just a few years, a recruit could become a decurion, leading his own squad (turma).

This rapid advancement path was well documented through various inscriptions and was beneficial to the empire, as it helped solidify loyalty to the emperor and improve the quality of soldiers posted on the frontiers. These chosen men were also well-housed, enjoying fresh air, sweet water from a nearby aqueduct, and easy access to some of the best amenities in Rome, such as fine bars and brothels.

Maximinus, initially regarded as a brute due to his size and strength, eventually distinguished himself by demonstrating intelligence and leadership potential. He would have had the responsibility of maintaining the discipline, training, and appearance of his turma, ensuring their armor and equipment were always in top condition.

Over time, the emperor realized that Maximinus was not merely a brawny soldier but someone capable of greater things.

Bust of Maximinus Thrax, Palazzo Nuovo, Musei Capitolini. Credits: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, CC BY-SA 4.0

As a result, Maximinus received support for advancement, likely being promoted to centurion and reassigned to one of the regular legions, possibly in the Danubian region where he was born. Upon his promotion to centurion, Maximinus would have been granted Roman citizenship, a significant achievement. By this point, he would have been around 35 years old, well-connected, experienced in warfare, and equipped with valuable leadership skills that would serve him well throughout his career. (Maximinus Thrax. From common soldier to emperor of Rome, by Paul N. Pearson)

Maximinus, the Emperor

Maximinus is generally not remembered kindly in historical accounts, and the critiques of his reign began early. Ancient historian Herodian characterizes him primarily as a soldier, lacking the qualities of a refined ruler.

His reign commenced after the assassination of Severus Alexander by rebellious troops, and Maximinus quickly became associated with the military. He distanced himself from Rome, spending his entire reign on the Rhine and Danube frontiers, expelling non-military personnel from his camp to maintain a purely military environment.

Although he achieved some success in campaigns against Germanic tribes, Herodian portrays him as a violent and greedy tyrant, which ultimately led to his downfall. His harsh taxation policies sparked a revolt, starting with Gordian I and later involving the Roman Senate.

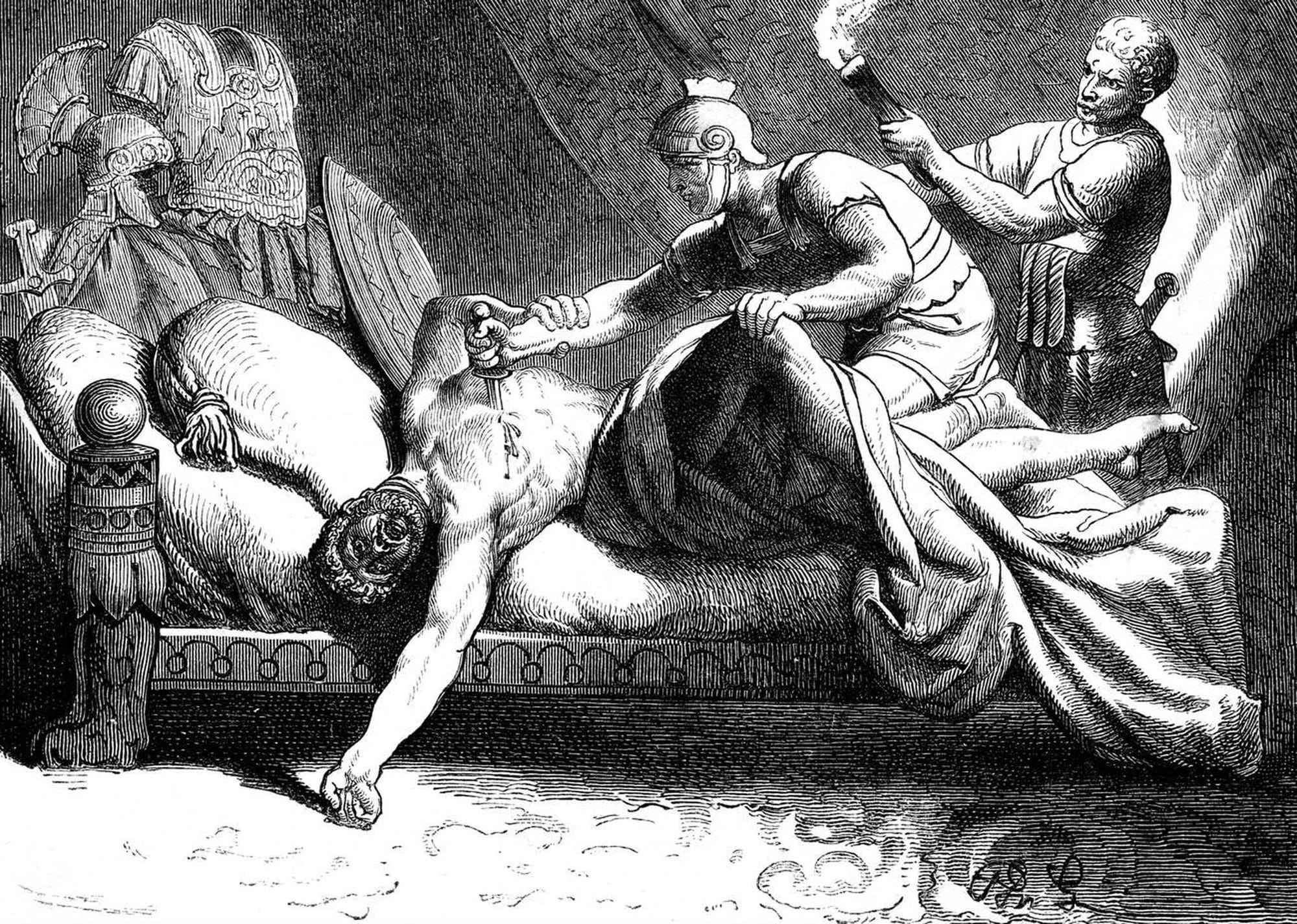

This opposition culminated in the appointment of Pupienus and Balbinus as co-emperors, which prompted Maximinus to lead an army into Italy. However, his military campaign stalled at Aquileia, where after he ordered the death of many of his generals, he and his son were assassinated by his own men, theirs heads displayed on pikes and sent to Rome, ending his reign in the same manner in which it had begun.

Maximinus, in History

Maximinus's character in historical accounts is largely defined by his background, described as "semi-barbarian." Herodian repeatedly references rumors of his origins as a shepherd in Thrace who rose to prominence due to his immense physical size. His supposedly barbaric roots are portrayed as influencing both his reign and approach to power, emphasizing his detachment from traditional Roman political norms.

“When Maximinus took control he brought about a great change, exercising his authority very harshly and with much fear.

He tried to change everything from a mild and altogether gentle monarchy into a cruel tyranny, aware of the hatred towards him for being the first person to rise from wholly insignificant origins to such great fortune.

But in his behaviour, just like his birth, he was by nature barbarian.”

In the context of imperial succession, Herodian presents Maximinus as a figure who sharply contrasts with the virtues of moderation and restraint, qualities embodied by Marcus Aurelius. While Severus Alexander is credited with elevating the Roman Empire into an aristocracy after the indulgences of Elagabalus, Maximinus is depicted as reverting to a tyrannical form of rule.

His reign is marked by ὠμότης (savagery) and εὐτελεία (low birth), which are central themes in Herodian’s portrayal of his character. These attributes underscore the moralizing framework Herodian applies, positioning Maximinus as the antithesis of a just ruler, with an emphasis on his brutality and humble origins, consistently associated with his reign.

This interpretation follows Herodian’s account but questions his motives. According to scholars, Maximinus wasn't necessarily hostile towards the aristocracy but was indifferent to them, contributing to their alienation. His reputation for greed, often highlighted in historical narratives, stems from his need to finance military campaigns. This portrayal suggests that Maximinus' primary failure was in ignoring civil responsibilities and public sentiment, not simply barbaric tendencies as Herodian might imply.

An analysis based on Herodian

Maximinus' reign, as portrayed by Herodian, is defined by his barbaric origins and low birth, which significantly shape his actions, especially towards the Senate and the military. His fear that his background would lead to a lack of respect from both the Senate and his subjects drives his violent tendencies (ὠμότης) and his isolation from all but his soldiers.

This isolation underscores his perceived disinterest in Roman political life and reflects the wider imperial savagery often associated with his character. He reports that Maximinus dismissed Alexander Severus’ senatorial appointees and surrounded himself exclusively with military men, further emphasizing his anti-senatorial stance and barbarian roots.

His narrative highlights Maximinus’ absence from much of the broader political discourse, particularly during the rebellions that dominate the latter part of the History. Even though Maximinus is not always at the forefront of the narrative, the underlying barbaric character he represents is felt throughout the story, as Rome spirals into violence and chaos under his rule. The themes of savagery and imperial corruption are central, as power shifts unpredictably, with the Senate and Roman citizens turning against the army.

This portrayal is less concerned with an objective account and more with creating a commentary on imperial character. In Maximinus’ reign, the moralizing themes of barbarism and violence are fully developed, reflecting the culmination of the emperor's influence on Rome's descent into disorder.

His account of Maximinus begins with the emperor on the frontier, highlighting his survival of two attempted coups before leading an invasion of Germany. Though militarily successful, Maximinus is portrayed as a ruler despised by all sectors of Roman society—he abused the elite, the people, the plebs, and even the soldiers.

Despite acknowledging Maximinus’ military competence, especially his potential to conquer all of Germany, Herodian quickly undercuts any praise by focusing on the emperor’s broader negative impact on Rome. Maximinus’ reign is framed not just as poor governance but as a fundamental threat to the empire, casting him as a barbarian ruler detrimental to Roman society.

“He would have been raised to a good reputation from his deeds had he not been so oppressive and fearsome towards his own people and subjects.

For what was the point in destroying barbarians when there were more deaths happening in Rome itself and among the subject nations?

What was the point in carrying off plunder and prisoners from the enemy while stripping and robbing his own people of their possessions?”

He continues presenting Maximinus as a ruler who initially shows promise as a general but quickly reverts to a barbarian stereotype. Away from the frontier, Maximinus inspires fear and distances himself from Roman identity, blurring the line between the Roman emperor and barbarian invader. His military success brings suffering not only to his enemies but also to his own people, as his violent tactics turn inward, threatening Rome itself.

One of the main themes is the contrast between Maximinus' low-born, insignificant background with the high status of his victims, including members of the elite like former consuls. Maximinus abuses his power by fabricating charges against them and humiliating the elite. His greed extends beyond the wealthy to public funds, with Maximinus seizing money meant for grain supplies, festivals, building works, and even temple treasures.

The emperor's actions provoke public outrage, leading to widespread grief and resistance. Herodian emphasizes that Maximinus' barbaric nature fully manifests when he targets the people and temples of Rome, making it appear as though Rome were under siege by its own ruler. This reinforces Herodian’s portrayal of Maximinus as a foreign, external threat to the Roman state, both in his nature and his governance.

Herodian's depiction of opposition to Maximinus is completed with the inclusion of the soldiers, though their role is treated more briefly and somewhat arbitrarily compared to the Senate and the people. The soldiers' discontent stems from the reproaches of their relatives and friends, blaming them for Maximinus' actions.

This is an unusual cause for military unrest in the History, as soldiers typically oppose emperors due to excessive discipline or perceived weakness. Here, family influence uniquely shapes the soldiers' dissatisfaction, marking the only instance before Maximinus' assassination when the troops display any hostility toward him.

Maximinus is portrayed as universally hated, with the soldiers joining the Senate and the people in opposition. The soldiers, tied to Rome's metaphorical household (τα οἰκεῖα), engage with other societal groups, reinforcing their unity against Maximinus, who remains an external, barbarian figure.

At the end, the overall effect of this short biography is not just to highlight universal hatred, but to frame Maximinus as a direct threat to Rome. He is depicted as a barbarian enemy, more interested in harming his own people than defending them. This backdrop of social unity against Maximinus sets the stage for the rebellions that follow, confirming that he was both despised and fundamentally alien, to Rome.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: