Macrinus’ True Story: Gladiator 2’s Power Player and Rome’s Brief Emperor

In the records of Roman history, Marcus Opellius Macrinus stands as a unique, and often overlooked figure.

Through Roman history, few figures are as intriguing as Marcus Opellius Macrinus, the empire’s first ruler from the equestrian class. Propelled into the limelight after the assassination of Caracalla, Macrinus’ rise to power marked a dramatic shift in Rome’s imperial politics. Known more for his administrative acumen than military prowess, Macrinus faced immense challenges during his brief reign (217–218 CE).

Struggling to stabilize an Empire rife with internal discord and external threats, his rule unraveled as swiftly as it began. Immortalized in Gladiator II, where Denzel Washington’s portrayal breathes life into his character, the real Macrinus’ journey from a background in law to the imperial throne remains an indication to the volatility of Roman politics and the precariousness of power.

What’s in a Name?

In this study, “Nomen Antoninorum: Macrinus and the Politics of Name Power", Scholtemeijer examines Emperor Macrinus' political strategy of adopting the Antonine name to legitimize his reign after the assassination of Caracalla. Macrinus, a man of non-senatorial origins and the first emperor to rise from the ranks of the equestrian class, faced an uphill battle in securing his position.

Recognizing the enduring prestige of the Antonine dynasty, Macrinus attempted to appropriate its legacy by granting his son Diadumenian the name Antoninus. This move aimed to evoke the memory of emperors like Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, revered for their just and stable rule. The study emphasizes how the Antonine name had become a symbol of imperial authority and moral governance.

However, Scholtemeijer reveals the irony of Macrinus’ maneuver: while the name carried significant weight, it was insufficient to mask his lack of a legitimate claim to the throne or to secure the loyalty of key groups such as the army and Senate. The Historia Augusta offers a scathing critique of this tactic, portraying Macrinus’ appropriation of the Antonine name as a desperate and ultimately hollow gesture.

Scholtemeijer highlights the broader implications of this episode, illustrating how Roman emperors frequently relied on symbolic acts to bolster their legitimacy. Yet, as Macrinus' brief reign (217–218 CE) demonstrates, such strategies often failed without the substantive qualities of leadership, military success, and popular support. The article provides a compelling lens into the delicate balance between name, legacy, and power in Roman imperial politics.

Macrinus’ Struggle for Legitimacy: Power, Politics, and Family Dynamics in a Short Reign

A key issue surrounding Macrinus’ brief reign is how he sought to legitimize his rule. Evidence from literary, epigraphic, and numismatic sources indicates that Macrinus aimed to establish a dynastic succession by positioning his son, Diadumenian, as his heir.

Understanding how Macrinus framed his relationship with both the Severan dynasty and his own family is crucial to analyzing his attempts to integrate himself, as a usurper, into the imperial lineage. Another significant aspect is Macrinus’ political program. While critics argue that the short duration of his reign prevented him from implementing a cohesive agenda, traces of development can still be identified.

Macrinus inherited numerous challenges stemming from Caracalla’s failed policies, which he was forced to address. Additionally, Macrinus’ downfall can be attributed to the intense power struggle between the army, the equestrian bureaucracy, and the imperial family.

His reign faced immediate challenges from the Syrian branch of the Severan dynasty, driven by the efforts of Julia Domna’s female relatives. Examining the individuals involved in this struggle, particularly the influential Severan women, sheds light on the dynamics of imperial families during this period and the substantial political power women could wield.

A Precursor to Crisis and a Reflection of Rome's Fragile Stability

In April 217, Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, widely known as Caracalla, was assassinated, leaving a power vacuum in the Roman Empire. The initial nominee to succeed him, Praetorian Prefect Oclatinius Adventus, declined the position due to his age, and the role fell to his colleague, Marcus Opellius Macrinus.

Hailing from North Africa and of equestrian rank, Macrinus became the first non-senatorial emperor of Rome.

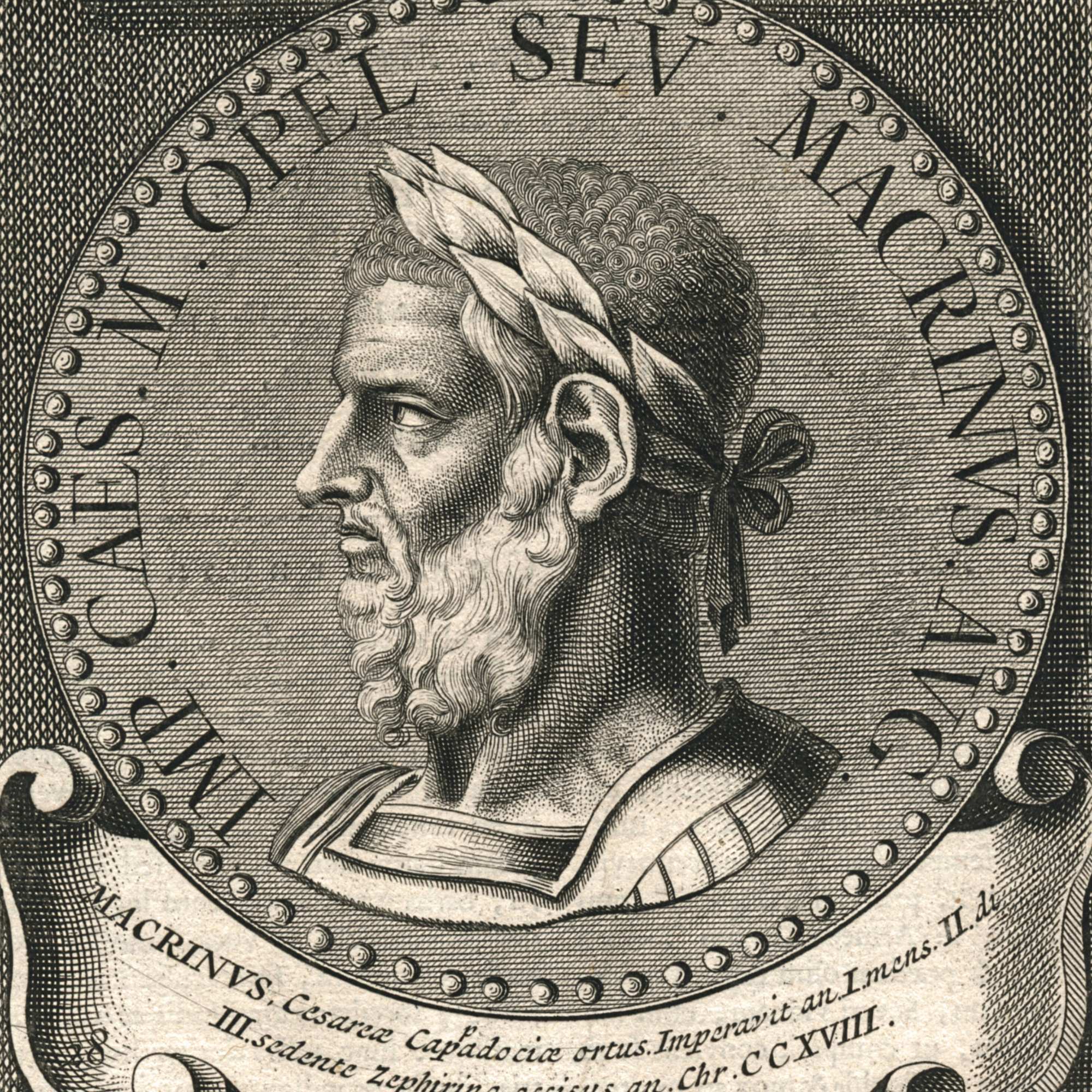

A gravure of a medallion depicting Roman emperor Macrinus. Public domain

Pliny the Younger and Dio Cassius both depict Macrinus’ rise as a product of necessity rather than popular support. Despite this, Macrinus' ascent was a turning point in Roman history, marking the increasing influence of the army in imperial succession. However, his reign, lasting only 14 months, was fraught with challenges, including unresolved issues from Caracalla's policies and immediate competition from the Severan dynasty.

“Macrinus was a Moor by birth, from [Mauretania] Caesarea, and the son of most obscure parents, so that he was very appropriately likened to the ass that was led up to the palace by the spirit; in particular, one of his ears had been bored in accordance with the custom followed by most of the Moors.

But his integrity threw even this drawback into the shade.

As for his attitude toward law and precedent, his knowledge of them was not so accurate as his observance of them was faithful.

It was thanks to this latter quality, as displayed in his advocacy of a friend's cause, that he had become known to Plautianus, whose steward he then became for a time.

Later he came near perishing with his patron, but was unexpectedly saved by the intercession of Cilo, and was appointed by Severus as superintendent of traffic along the Flaminian Way.

From Antoninus he first received some brief appointments as procurator, than was made prefect, and discharged the duties of this office in a most satisfactory and just manner, in so far as he was free to follow his own judgment.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History

Macrinus sought to legitimize his rule by planning a familial succession through his son, Diadumenian. He also aimed to establish connections to Rome's imperial past while addressing domestic and foreign policy challenges, particularly in the East. Despite efforts to stabilize his rule, Macrinus faced fierce opposition from Julia Domna’s Syrian relatives, leading to his eventual downfall and the rise of Elagabalus in 218.

Scholars often dismiss Macrinus as a minor and ineffectual emperor, but his reign reflects the fragile power dynamics of the third century.

Marble bust of Roman Emperor Macrinus. Credits:

Francesco Bini, CC BY-SA 4.0, Upscaling by Roman Empire Times.

His tenure, marked by attempts to restore order and navigate the complex interplay of military, bureaucratic, and familial forces, foreshadowed the challenges faced by later emperors during the period of Roman instability known as the Crisis of the Third Century. (Change and discontinuity within the Severan dynasty: the case of Macrinus, by Andrew G. Scott)

Has Macrinus Plotted against Caracalla or not?

The events surrounding the murder of Emperor Caracalla are recounted with some variations. Herodian describes messengers arriving in Syria with a bundle of official letters. Caracalla, preoccupied with chariot racing, asked his Praetorian Prefect, Macrinus, to review the letters.

Among them, Macrinus allegedly discovered incriminating information against himself. Dio Cassius, however, provides a less dramatic and more plausible version, stating that Caracalla had entrusted routine correspondence to his mother, Julia Domna, a claim supported by the discovery of a letter from Julia to Ephesus.

According to Dio, Macrinus was privately warned, and the delayed official letters were sent to Julia at Antioch, who was tasked with reviewing them. Both accounts, though different, suggest Macrinus was made aware of accusations against him. (Emperors at Work, by: Fergus Millar). Cassius Dio and Herodian both recount the assassination of Caracalla through narratives shaped by hostility toward Macrinus, likely influenced by the perspective of his successor, Elagabalus.

However, their accounts differ due to their distinct historical viewpoints and attitudes toward the key figures involved. Dio’s version reflects his belief that Macrinus exceeded the limits of his social rank, portraying him in a negative light. In contrast, Herodian frames the events to align with a traditional tyrant-slaying narrative, drawing parallels to historical accounts of Harmodius and Aristogeiton as well as the assassination of Caligula.

The assassination of Caracalla in April 217 presents a challenging narrative for historians due to its conspiratorial nature and reliance on questionable sources. Cassius Dio and Herodian, both contemporary historians, provide critical yet differing accounts of the event, reflecting their perspectives on Caracalla, Macrinus, and the nature of power in the Roman Empire.

The Conspiracy Narrative

Macrinus is consistently implicated as the instigator of Caracalla's assassination. However, the narrative connecting him to the plot likely developed after his death, as part of a hostile tradition established by his successor, Elagabalus. This tradition aimed to delegitimize Macrinus' reign and justify Elagabalus' ascension.

Elagabalus formally condemned Macrinus through a damnatio memoriae, executed many of his associates, and accused him of treachery in letters to the Senate. Both Dio and Herodian agree that Macrinus selected Julius Martialis, an evocatus in Caracalla’s bodyguard, to carry out the murder.

Motivated by personal grievances against Caracalla, Martialis assassinated the emperor during a visit to a moon god’s temple near Carrhae. Dio attributes Martialis' actions to a grudge over not being promoted to centurion, while Herodian claims Caracalla had recently executed Martialis’ brother and repeatedly insulted him as cowardly and effeminate.

Herodian also notes that Martialis was a client of Macrinus, strengthening the connection between the two.

A possible representation of a secret meeting between Macrinus and Martialis. Illustration: Midjourney

Cassius Dio’s Perspective

Dio’s account reflects his disdain for both Caracalla’s tyranny and Macrinus’ overreach. Dio portrays Macrinus as a cowardly Moor who, despite some virtuous traits, was unfit to be emperor due to his non-senatorial status.

He criticizes Macrinus for aspiring to imperial power, describing him as motivated by fear of Caracalla and an unworthy desire for the throne. Dio’s assessment of Macrinus is deeply influenced by his broader belief that the social hierarchy and senatorial dignity were critical to the harmony of the Roman monarchy. Dio’s condemnation is evident in his description of Macrinus’ actions:

- Fear drove Macrinus to conspire against Caracalla when he learned of prophecies predicting his rise to power.

- Dio dismisses Macrinus' legitimacy, remarking that his lowly origins undermined his right to rule.

- In his eulogy, Dio states that Macrinus might have been admired had he chosen a senator to succeed Caracalla rather than seizing power himself.

Herodian’s Perspective

Herodian’s narrative focuses on character-driven motives and ties Macrinus’ actions to conspiracy themes seen in other historical tyrannicide accounts, such as the slayings of Caligula and the Pisistratids. While Herodian agrees that Macrinus instigated the murder, he emphasizes insults as a key motivation: Caracalla frequently mocked Macrinus for his lack of military prowess and luxurious lifestyle, accusing him of effeminacy and cowardice.

Herodian suggests that these humiliations compelled Macrinus to act, portraying him less as an ambitious usurper and more as someone reacting to a tyrant’s provocations. Herodian contrasts Caracalla’s behavior, characterized by cruelty and extravagance, with Macrinus' attempts to end tyranny.

However, he acknowledges that Macrinus himself did not murder Caracalla, transferring the motivations for the act to Martialis.

The death of the Roman Emperor Caracalla, assassinated with a sword, by Martialis. Credits: Tancredi Scarpelli, Meisterdrucke. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

The Role of Julius Martialis

Both historians agree on Martialis’ role as the assassin: Martialis killed Caracalla during a roadside stop, only to be slain by Caracalla’s bodyguards afterward. Dio notes that the people of Rome wanted to honor Martialis as a tyrannicide, though Herodian omits this detail.

The assassination of Caracalla, as recounted by Dio and Herodian, is heavily shaped by their attitudes toward Macrinus and Caracalla. Dio condemns Macrinus for disrupting the social order and pursuing power he did not deserve. Herodian frames the event within a broader narrative of tyrannicide, emphasizing the insult-driven motivations of both Macrinus and Martialis.

Together, their accounts reflect the complexities of imperial power struggles and the contested legacy of Macrinus as both a conspirator and a short-lived emperor.

“You are familiar with the course of my life from its very beginning.

You know my inclination toward uprightness of character and are aware of the moderation with which I previously managed affairs, when my power and authority were little inferior to that of the emperor himself.

For that reason, and since the emperor sees fit to put his trust in the praetorian prefects, I do not think it necessary for me to address you at great length.

You know that I did not approve of the emperor's actions.

Indeed, I frequently risked my life on your behalf when he listened to random charges and attacked you without mercy.

He criticized me harshly too, often publicly complaining about my moderation and my restraint in dealing with those under my authority, and ridiculing me for my easygoing ways and mild manner.

He delighted in flatterers and men who encouraged him to cruelty and gave him good reason for his savagery by arousing his anger with slanderous charges.

These people he considered his loyal friends.

I, on the other hand, have from the beginning been mild, moderate, and agreeable.

We brought the war against the Parthians to a conclusion, a critical struggle involving the safety of the whole Roman empire.

In our courageous opposition to the Parthians we proved in no way inferior to them, and in signing a treaty of peace we made a loyal friend instead of a dangerous enemy of a great king, who had marched against us at the head of a formidable army.

Under my rule all men shall live in peace, and senatorial rule shall replace the autocracy.

But let no one think me unworthy of my post, and let no one believe that Fortune blundered in raising me to this position, even though I am of the Equestrian order.

For what advantage is there in nobility of birth unless it be combined with a beneficent and kindly nature?

The gifts of Fortune fall upon the undeserving also, but it is the excellence of his own soul which brings every man his measure of personal glory.

Nobility of birth, wealth, and the like are presumed to bring happiness, but, since they are bestowed by someone else, they deserve no praise.

Virtue and kindness, on the other hand, besides commanding admiration, win a full measure of praise for anyone who succeeds by his own efforts.

What, may I ask, did the noble birth of Commodus profit you?

Or the fact that Caracalla inherited the throne from his father? Indeed, having received the empire as legal heirs, the two youths abused their high office and conducted themselves insolently, as if the empire were their own personal possession by right of inheritance.

But those who receive the empire from your hands are eternally in your debt for the favor, and they undertake to repay those who have done them previous good services.

The noble ancestry of the highborn emperors leads them to commit insolent acts out of contempt for their subjects, whom they regard as far below them.

By contrast, those who come to the throne as a result of temperate behavior treat the post with respect, since they secured it by toil; they continue to show to those who were formerly their superiors the same deference and esteem they were accustomed to show.

I intend to have you senators as my associates and assistants in managing the empire, and I intend to do nothing without your approval.

You shall live in freedom and security, enjoying the privileges of which you were deprived by your nobly born emperors and which Marcus, of old, and Pertinax, recently, undertook to restore to you; the latter also are emperors who came to the throne from private circumstances.

Surely it is better for a man to provide his descendants with the glorious beginnings of a family line than, having inherited ancestral glory, to disgrace it by outrageous behavior."

Herodes, Book Five, Macrinus, Elagabalus — Macrinus’ letter to the senate

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: