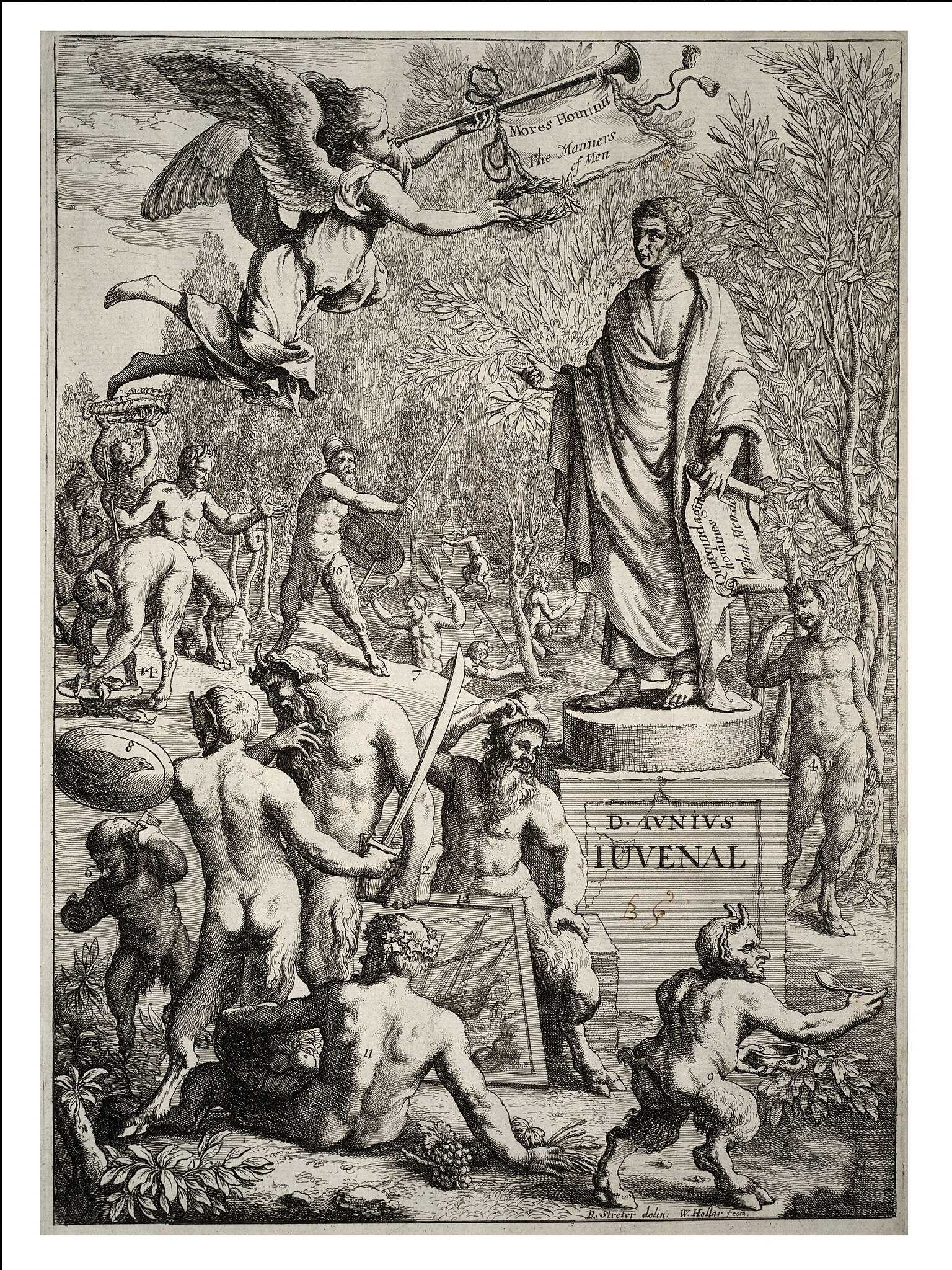

Juvenal: The Poet Who Held a Mirror to Rome

Juvenal’s satires turn rage into art, exposing Rome’s vices with a voice both fierce and sublime. His life remains shadowed—shaped by exile, poverty, and suspicion—but his verses endure as monuments of indignation and moral force.

In the shadow of emperors and under the weight of imperial excess, Juvenal emerged as Rome’s fiercest satirist. His sixteen satires, composed in biting hexameters, turned indignation into art, exposing hypocrisy, corruption, and moral decay with an irony so sharp it still cuts across centuries. To read Juvenal is to encounter a voice both enraged and enduring, one that forced Romans to confront the vices they preferred to ignore.

The Shadowed Life of Juvenal

The life of Juvenal is shadowed by uncertainty. What survives of him comes only in fragments—hints from his poems and scattered traditions—leaving much of his biography obscure. From the Satires, his later years can be traced with some certainty, yet their focus on the Domitianic age suggests a hidden trauma in his early life. According to the scholiasts, that shadow was exile—imposed by Domitian after Juvenal penned a lampoon against the actor Paris, accusing him of manipulating equestrian promotions.

The inscription, if genuinely his, implies that Juvenal himself once began an equestrian career. His failure to advance within it may have fueled the biting satire that provoked his banishment and left a lasting mark on both his fortunes and reputation.

The Poet Revealed Through Satire

Juvenal’s career is difficult to trace from external testimony. Only a single contemporary mentions him, and for more than a century after his death, references are rare and contradictory. As the last voice of the Silver Age, his biography remains uncertain, but his poems make up for the silence of history.

Though he never openly sets himself on stage, his character, outlook, and circumstances emerge from every line with unmistakable force. His voice—harsh, indignant, and unyielding—imprints itself on his work as clearly as a watermark, leaving readers in no doubt about the man behind the satires.

Tracing Juvenal’s Life Through Fragmentary Evidence

The life of Juvenal can be approached through three distinct sources, as already mentioned, each offering clues of uneven value: his own poetry, the testimony of other writers, and an uncertain inscription. His satires, published in collections during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian, are the most reliable witness. Because satire mixes moral reflection with topical allusion, the dating of individual poems can only be approximated, and even then with caution.

Juvenal’s references are often anachronistic—invoking examples from Domitian’s reign in works issued decades later—so the poems reveal character more clearly than chronology. What emerges is a man who speaks little of himself but whose rare autobiographical remarks carry the weight of truth.

Other writers provide far less. Martial, his only contemporary witness, offers a brief mention. Later authors such as Sidonius and Malalas repeat only the tradition of his exile, while scholiasts in the Pithoeanus manuscript added details that are often demonstrably false or invented. The third source, an inscription now lost but once thought to bear his name, remains contested. If genuine, it would shed light on an important phase of his career, yet scholars disagree on whether it can be tied to him at all.

Taken together, these fragments allow only a partial reconstruction: the poems give a relatively secure view of Juvenal’s later years, the scholia suggest an account of his exile, and the inscription—if authentic—hints at his early life. The challenge lies in drawing these strands into a coherent picture that connects his personal fortunes with the distinctive character of his poetry.

From Indignation to Resignation: The Arc of Juvenal’s Life

Juvenal’s early poems erupt with volcanic fury, but as the years pass, his satire loses its initial fire, shifting into bleak generalizations or sharp trivialities. His greatest energy lies in the works of Books I and II, composed in the first decade of the second century, after which his inspiration gradually waned.

Scholars have long debated this decline: some, like Gibbon, saw it as a natural stylistic change, while others proposed that the later satires were the work of an imitator. Yet the evidence of Juvenal’s own voice shows no need for such inventions; his indignation was real, but it dulled with time.

The outlines of his life can be pieced together from his poems. Born around 55 CE, likely in Aquinum to free but non-noble parents, he received a standard education and spent his youth in obscurity. By the time his first satires appeared, around 100–105 CE, he was already middle-aged, living modestly in Rome as a client, occasionally returning to Aquinum.

His silence about his early life is striking, but his vivid accounts of Domitian’s Rome leave no doubt that he had observed it closely.

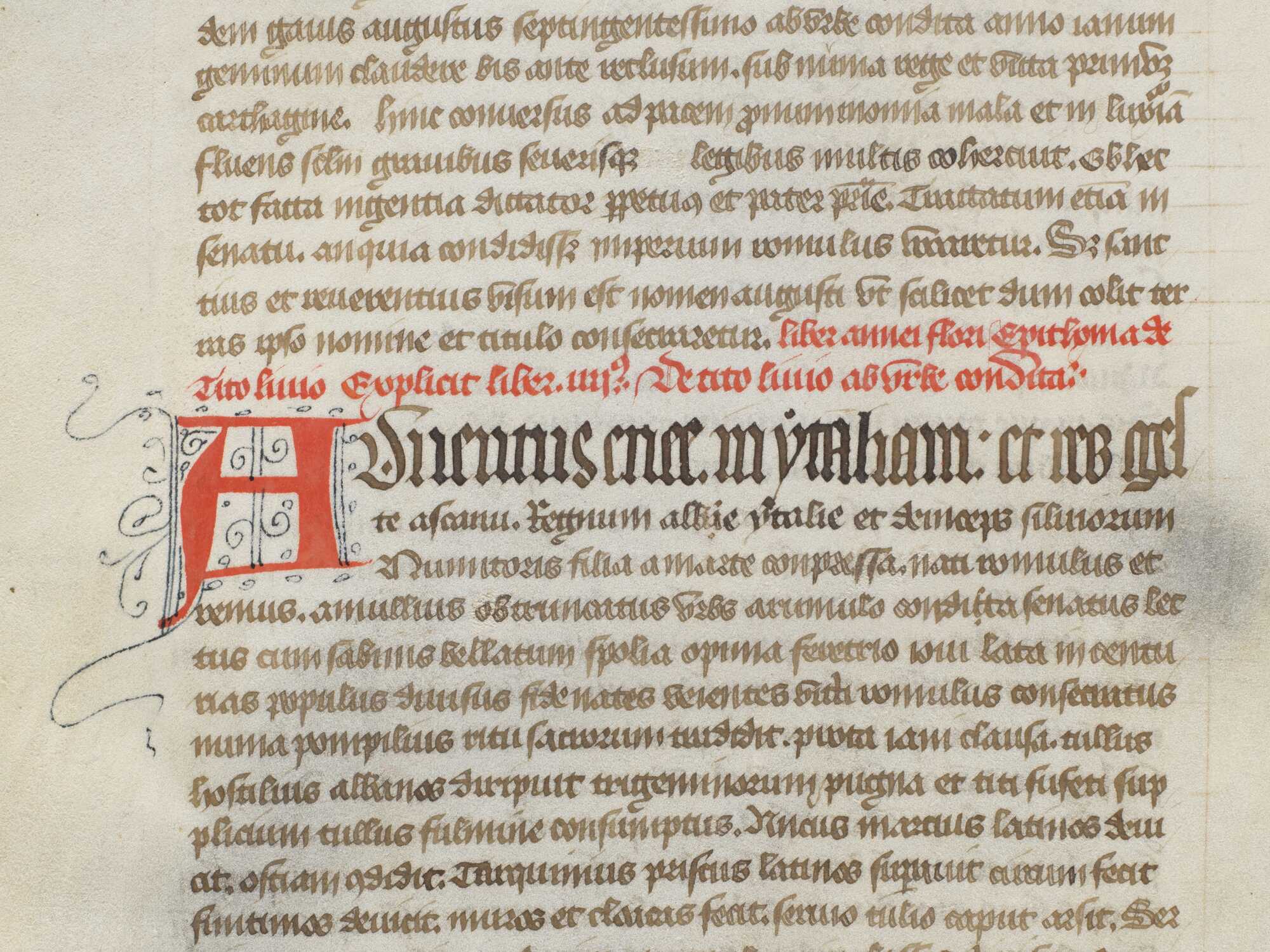

A manuscript from Juvenal’s Satires. Public domain

Book I (satires 1–5) marked his arrival, followed a decade later by Book II (satire 6), which reflects events around 115 CE, including a comet and the great Antioch earthquake. Book III (satires 7–9) laments the poor rewards of literature and contains his only praise of a Roman emperor—probably Hadrian, whose refoundation of the Athenaeum encouraged poets.

Books IV and V belong to his old age: satire 10 dwells on the burdens of growing old, while his later poems reveal that he had acquired modest property, a house in Rome, perhaps even land near Tibur. By then, his tone had softened; poverty and injustice remained themes, but with less sting than before.

Book V, completed around 127 CE, also reveals personal experiences. Juvenal claims to have traveled to Egypt, describing a local conflict so precisely that archaeological discoveries centuries later confirmed his accuracy. His distaste for Egyptian society was clear, yet the detail proves he had seen the country firsthand.

Throughout, one constant remains: his indignation at the injustice of the Domitianic era, a hatred that animated his satire but inevitably weakened as the memory of those years faded. His last works still bite, but the hornet’s sting had dulled, leaving behind a voice more resigned than enraged.

Martial’s Friendship and the Tradition of Exile

Among Juvenal’s contemporaries, only Martial mentions him directly, addressing three poems to his friend. In one of them, Martial calls him facundus—“eloquent” or “gifted with style.” Some later critics imagined this meant Juvenal was merely a declaimer, but Martial uses the word freely of Virgil, Cicero, and others. It simply marks him as a man of letters.

Another poem, written after Martial’s return to Spain, paints a less flattering picture: Juvenal, unlike Martial who enjoys rustic peace, is portrayed in Rome as a poor client haunting the Subura and the doorways of the powerful. These brief glimpses tell us only that Juvenal was active in Rome, writing, in the 90s and early 100s. The shift in tone also hints that the two poets may have drifted apart.

After Martial, Juvenal vanishes from the historical record until the fourth century, when antiquarian interest in Silver Age authors revived and scholia were added to his works. The silence of his own age suggests he never achieved great prominence nor moved in the circles of the powerful.

So when we speak of the Juvenal scholia (especially the P scholiasts on the Codex Pithoeanus), we mean the anonymous annotators who copied and commented on Juvenal’s text centuries after he wrote.

They’re not “scholars” in the modern sense, but rather scribes or commentators from Late Antiquity or the early Middle Ages, whose notes sometimes preserve valuable traditions — though also a lot of inventions.

What later survives of his biography clusters around one tradition: that Juvenal was exiled for verses thought to attack a favorite of the emperor. Ancient lives and scholia say he wrote a bitter aside about the pantomime actor Paris, implying that success in equestrian offices was more easily gained by pleasing a stage dancer than by noble merit. The lines run:

“Quod non dant proceres, dabit histrio. Quodcunque ostendis mihi sic, incredulus odi.”

“What the nobles will not grant, the actor will give. Show me such a path to honors, and I despise it in disbelief.”

Though ostensibly mocking a dead performer, the verses were taken as a veiled attack on the living regime. Suspicion fell upon Juvenal, and he was banished.

Traditions vary on which emperor ordered the punishment. Domitian, ever suspicious of hidden satire, is the most likely, though later sources also name Trajan or Hadrian. The biographies disagree in their details, some even claiming he was eighty when sent away, which would make Domitian impossible. Yet Domitian’s character and the fearful tone of Juvenal’s early satires fit well with an exile under his rule.

As for the place, accounts differ again. Some scholia state he was sent to the deserts of Egypt, perhaps the Great Oasis, others that he served at Syene (modern Aswan). Malalas places him in the Pentapolis on Egypt’s western edge. All agree it was far, harsh, and humiliating. The exile was disguised as an appointment to military command, but the bitterness that pervades his satires suggests it was felt as punishment rather than honor.

It mixes fact, folklore, and legend, and while not very reliable by modern standards, it sometimes preserves echoes of earlier lost sources. When he’s cited in Juvenal studies, it’s because his chronicle contains a garbled note about Juvenal’s exile — one of the few surviving late-antique traditions about the poet’s life.

Scholars usually treat Malalas’ testimony with caution, since it’s confused and heavily embroidered, but it shows how the story of Juvenal’s exile was circulating centuries later.

Whether imposed by Domitian or later emperors, the tradition of exile offers an explanation for Juvenal’s peculiar life: obscure in youth, suddenly fierce and indignant in his middle years, then fading into relative quiet. His silence about himself, his recurring fear of authority, and his hatred of Egypt all gain sharper meaning if exile truly shadowed his career.

The Lost Inscription and Juvenal’s Equestrian Hopes

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, antiquarians copied an inscription from a marble tablet in the church of San Pietro at Aquinum. By the time scholars investigated in the nineteenth century, the stone had vanished. The most reliable copy read:

CereRI SACRVM

d iuNIVS IVVENALIS

trib COH i DELMATARVM

II VIR QVINQ FLAMEN

DIVI VESPASIANI

VOVIT DEDICAVitqVE

SVA PEC

“Sacred to Ceres. D. Junius Juvenalis, tribune of the First Cohort of Dalmatians, duovir quinquennalis, flamen of the divine Vespasian, vowed and dedicated [this altar] at his own expense.”

If genuine, the inscription points to Juvenal himself—or another man with the same cognomen—beginning an equestrian career. The text records high civic honors: duovir quinquennalis (a five-year magistrate of Aquinum) and priest of the deified Vespasian, both positions granted to distinguished citizens. It also notes military service as a cohort commander, a typical post for a young knight entering imperial service.

Yet the reconstruction is uncertain. The copyist may have misread trib(unus) for praef(ectus), and nothing proves the dedicator was the satirist. Still, its location at Aquinum—the town Juvenal calls “tuum Aquinum”—and the altar’s dedication to Ceres, one of Aquinum’s chief deities and the only goddess Juvenal treats with reverence, make the identification plausible.

If the poet did set up this stone as a young knight, the implications are striking. He began with promise, wealth, and equestrian status, only to see his career thwarted. Advancement in the militia equestris depended on patronage and influence—what Juvenal bitterly describes in satire:

“Tu Camerinos et Bareas curas magna atria? Praefectos elopea facit, Philomela tribunos.”

“Do you look to the Camerini and Bareae, great men of noble halls? No—the stage makes men prefects, a Philomela makes them tribunes.”

Here the “actor’s suffrage” elevates men unworthy of office. If Juvenal himself had sought promotion through noble recommendation (suffragium) and been denied, the sting was personal. His satire became an outlet for disappointment, and, as tradition holds, earned him exile under Domitian. The confiscation of his property would explain his later poverty and his life as a dependent client in Rome.

The lost inscription, then, if truly his, casts Juvenal’s indignation in a new light: not only moral outrage, but the bitterness of a man who had once touched honor and wealth, only to lose both to injustice and imperial suspicion. (The Life of Juvenal, by Gilbert Highet, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association)

Juvenal Between Hypothesis and Evidence

Gilbert Highet’s “The Life of Juvenal”, offered a bold reconstruction: Juvenal born c. 55 CE at Aquinum, entering the equestrian career, exiled under Domitian for offending the regime, and later returning to publish his satires in a life marked by poverty and bitterness. Edward Courtney, in his “Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal”, approaches the same evidence with far greater caution.

Courtney refines the chronology by anchoring the satires to firmer historical references. He places Book I around 112 CE, Book II after 116, Book III under Hadrian in the 120s, and Book V about 130. This adjustment shifts Juvenal’s likely birth to c. 60 rather than Highet’s 55, since all his surviving work is shown to belong to middle or old age.

He is also more skeptical of the exile tradition. Where Highet accepted exile under Domitian as plausible, Courtney highlights the contradictions and anachronisms in the scholiasts and late biographies, stressing how little weight can be placed on them. Likewise, in discussing the Aquinum inscription, Highet leaned on Mommsen’s reconstruction; Courtney reviews later epigraphic scholarship and shows how uncertain its restoration really is, making it unlikely evidence for the poet himself.

The result is a less dramatic but more disciplined account: not the vivid personal story Highet constructed, but a pared-down biography in which the only secure facts are Martial’s testimony, the few allusions within the satires themselves, and the consistent hatred of Domitian that marks Juvenal’s verse.

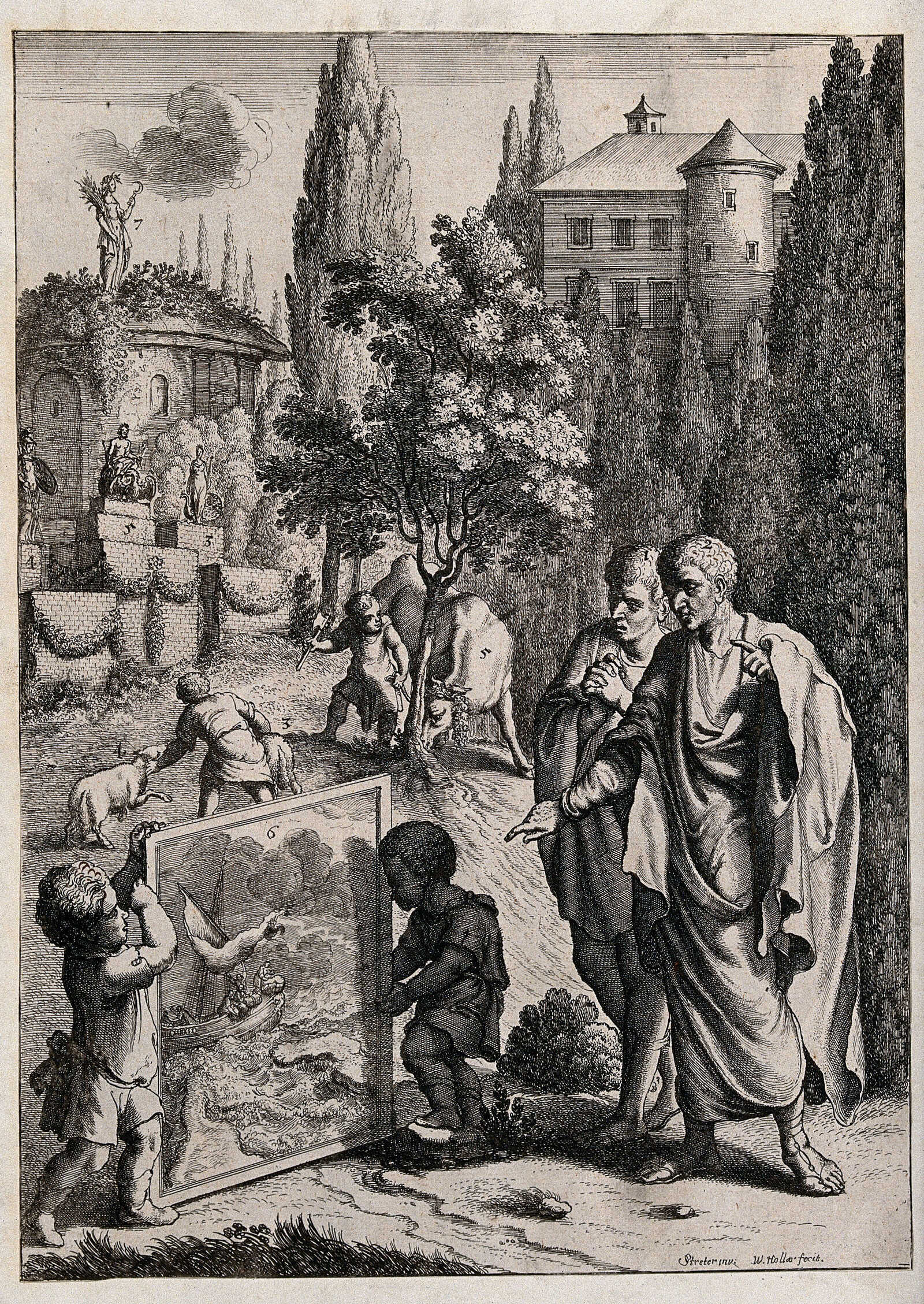

Juvenal’s influence in modern art: The comic Watchmen’s reference to Juvenal’s Quote ‘Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes’ (Who Watches the Watchmen). Credits: Xeni Jardin, Brian J. Matis, CC BY-SA 2.0, Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

The Sublime Power of Juvenal’s Satire

Juvenal’s satire is marked not merely by indignation but by a quality that elevates it to the level of the sublime. His harsh, unyielding voice, his choice of themes, and his rhetorical strategies combine to produce an overwhelming effect that goes beyond ridicule and moral protest. What makes Juvenal stand apart is the intensity with which he presents vice, corruption, and human folly: his language transforms these into vast, terrifying visions that evoke awe as well as repulsion.

The sublime in Juvenal arises from his preference for extremes. He does not dwell on minor faults but selects subjects that are monstrous in scale—tyranny, sexual depravity, social injustice, and the collapse of moral order. His invective is couched in hyperbolic images that expand the scope of his satire far beyond the immediate moment. Through exaggeration and intensity, he achieves effects that are less about realistic description and more about moral enormity.

A key feature is his use of rhetorical amplification. Instead of concise denunciation, Juvenal piles detail upon detail, building cumulative force until the reader is confronted with a vision that feels overpowering. This technique, drawn from the traditions of declamation, allows him to magnify indignation into something vast and awe-inspiring. His harsh diction, abrupt transitions, and violent metaphors all contribute to this elevated style.

Juvenal also aligns with the sublime through his emotional stance. His anger is not controlled wit, as in Horace, but an all-consuming passion. His voice suggests not amusement but moral outrage, bordering on despair. In passages where he presents the corruption of Rome as universal and inescapable, his vision acquires a grandeur born of hopelessness: the picture of a world irredeemably lost, painted in strokes of ferocity.

The sublime element in Juvenal’s satire helps explain its lasting appeal. Even when the historical circumstances fade, the sheer force of his rhetoric continues to impress. Readers are drawn not only to his moral judgments but also to the aesthetic experience of encountering language stretched to its limits in the service of indignation. His satire becomes less a record of Roman vice and more a monumental expression of human anger and disillusion.

Juvenal’s greatness lies in this transformation. His satires do not merely condemn; they overwhelm. By fusing invective with sublimity, he elevates satire to a new level, where it commands attention through terror, awe, and the sheer power of its voice. (Juvenal as Sublime Satirist, by William Kupersmith)

Juvenal remains a figure glimpsed more through his words than through history, a man whose life is half-lost but whose voice endures with unrelenting clarity. Whether truly marked by exile, disappointment, or the bitterness of thwarted ambition, his satires rise above circumstance to stand as monuments of moral anger. In them Rome is held to account, its vices magnified into visions at once terrifying and sublime.

What we cannot know of Juvenal the man, we still hear in Juvenal the poet: the echo of a fierce conscience that refused to be silent. Through Juvenal, Rome still speaks—its grandeur shadowed by corruption, its power mirrored in satire, its voice forever edged with rage.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: