Unlike Other Civilizations, the Romans Used These Methods to Cope With Winter Cold

By using from simple to ingenious techniques, Romans managed to keep warm during the winter months.

There is not a simple answer as to 'how the Romans kept warm'; the Roman Empire used various methods to tackle the winter conditions, with some being truly ingenious for their time. Beneath the impressive structures of Roman architecture lay an equally extraordinary innovation: the hypocaust heating system. This underfloor design transformed how the Romans maintained warmth, providing heat to villas, baths, and even some city homes during the colder months.

By skillfully utilizing fire and controlled airflow, the Romans developed a heating method that was both efficient and luxurious. The hypocaust, along with other advanced techniques, highlights their ability to merge practicality with comfort, leaving a lasting legacy of engineering brilliance.

As Vitruvius said in his Ten Books of Architecture,

“Divine providence has so ordered it that the metropolis of the Roman people is placed in an excellent and temperate climate, whereby they have become the masters of the world.”

Still, during the winter, the Romans were cold and needed some heating solutions.

The Romans employed a variety of techniques to stay warm during colder months, showcasing their resourcefulness and ingenuity. Among their methods were some of the earliest forms of central heating, portable heaters, warm beverages, and a practical approach to utilizing sunlight. In winter, they abandoned the cooler, north-facing rooms favored in summer and shifted to west-facing spaces, where the sun's warmth and light were more abundant, following Vitruvius’ advise:

“I shall now describe how the different sorts of buildings are placed as regards their aspects. Winter triclinia and baths are to face the winter west, because the afternoon light is wanted in them; and not less so because the setting sun casts its rays upon them, and by its heat warms the aspect towards the evening hours.

Bed chambers and libraries should be towards the east, for their purposes require the morning light: in libraries the books are in this aspect preserved from decay; those that are towards the south and west are injured by the worm and by the damp, which the moist winds generate and nourish, and spreading the damp, make the books mouldy.”

Baths, Light, and Heat

Windows play an essential role in architecture, yet their design and usage have varied significantly over time. In medieval Romanesque churches, small windows punctuated thick stone walls, creating dimly lit interiors. In contrast, the Gothic style later embraced expansive windows supported by external buttresses. Interestingly, Roman architecture predating these styles frequently featured large windows, particularly in public bathhouses of the Early Empire.

Seneca, writing in the first century AD, offers an insightful commentary on this trend, noting that baths of his time were designed to let in sunlight throughout the day through wide windows. He remarks with a hint of nostalgia on the simpler, darker baths of the Republic, contrasting them with the sunlit, grandiose structures of the imperial era.

Roman baths, particularly during the Early Empire, represented significant advancements in both architectural and technological innovation. Scholars like Yegul and Nielsen have highlighted these contributions, which included the integration of Greek and Roman styles, the introduction of hypocaust systems to heat large spaces, and the invention of tubuli—hollow walls that ensured even heat distribution and prevented condensation.

The Romans’ architectural ingenuity extended to using large south-facing windows to harness sunlight for heating and lighting. Glassblowing techniques had advanced by this period, enabling the production of flat panes of glass for windows. These developments, combined with vast aqueduct systems, allowed the baths to accommodate thousands of visitors in comfortably heated environments.

In 1956, Edwin Thatcher, an architectural historian, highlighted the sophistication of Roman heating methods, describing the unglazed, south-facing windows of Ostia’s second-century Forum Baths as a remarkable demonstration of radiant heating. He argued that Roman engineers had a deeper understanding of radiant heat's potential than modern architects, allowing them to create expansive, open spaces unmatched in contemporary designs. The Romans’ strategic use of sunlight in these baths exemplifies their advanced grasp of architecture, engineering, and sustainable heating practices.

Interdisciplinary Insights into Heating Systems

In recent decades, the focus on everyday life and microhistory has become central to studies in history, art history, and archaeology. This shift has brought increased attention to ancient technologies, including Roman innovations. While archaeologists have advanced our understanding of Roman heating systems, the technical complexities often demand interdisciplinary collaboration, which is becoming more common yet remains underutilized.

For example, the study of heat transfer in Roman baths, or thermae, requires both engineering expertise and archaeological evidence. Despite attempts to measure temperatures in Roman homes and baths based on ancient texts, archaeological finds, and experimental reconstructions, such efforts often face limitations due to incomplete data. As a result, any conclusions must remain open to revision with future discoveries.

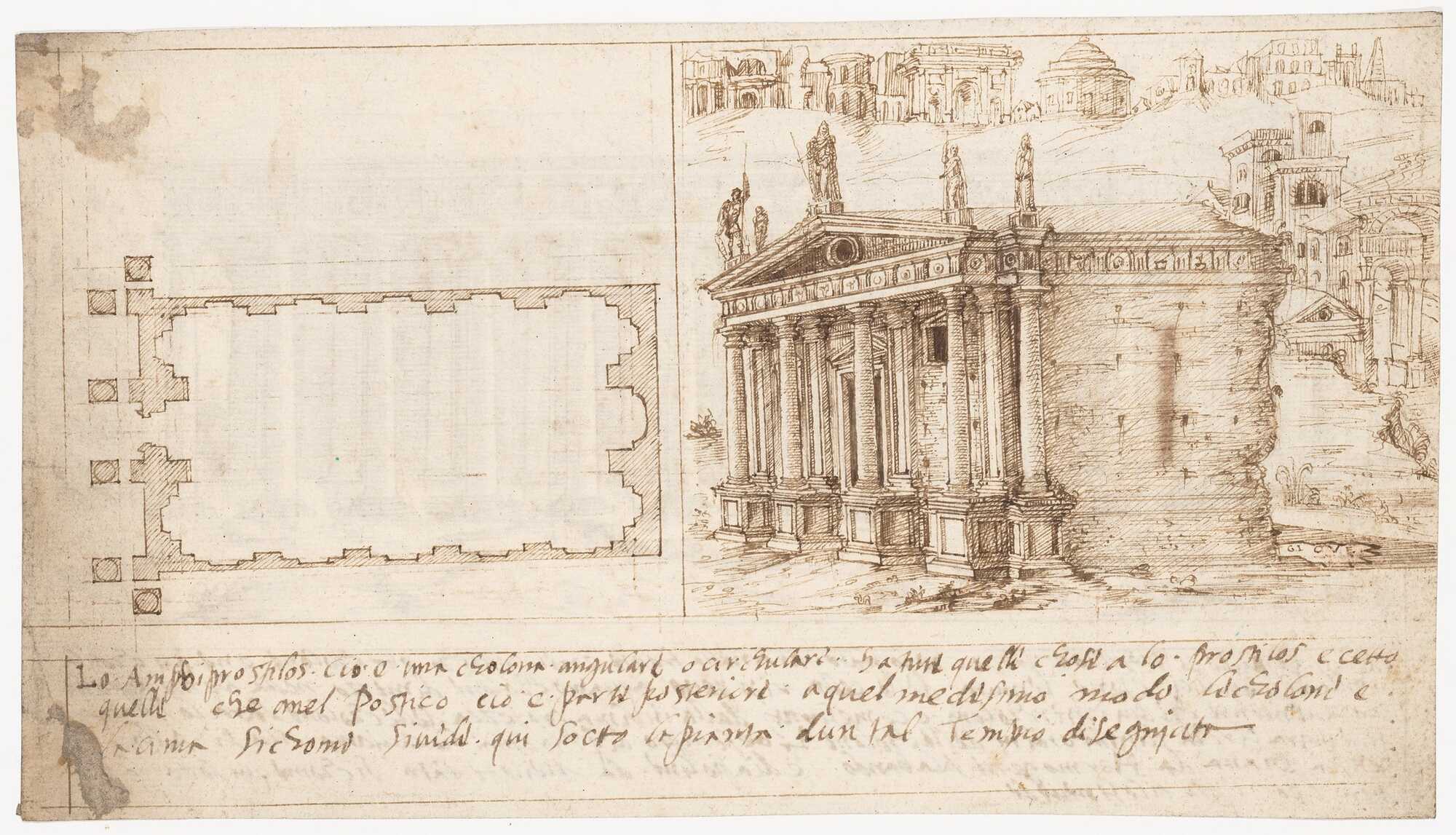

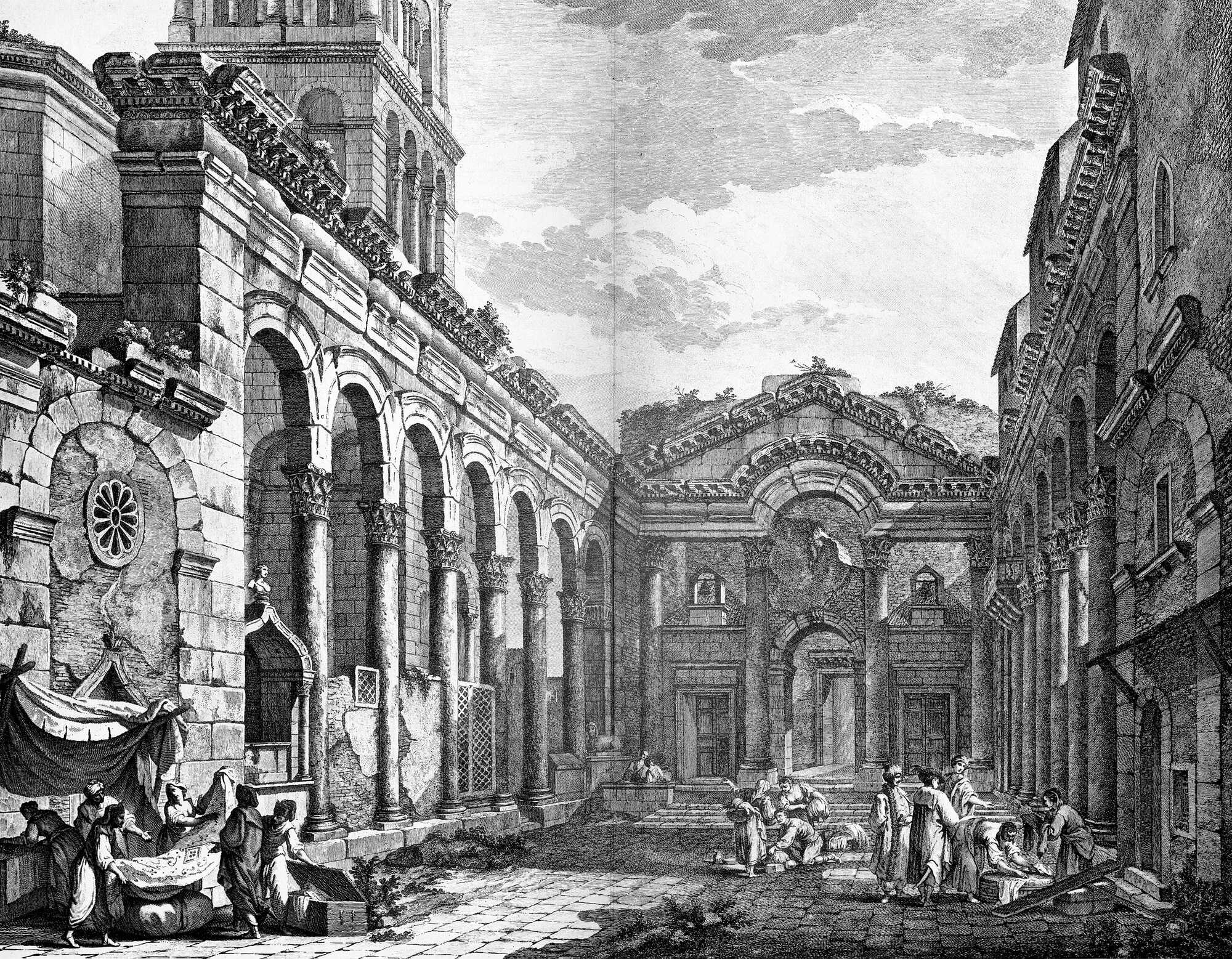

A notable case study is the heating system of the baths in Diocletian’s palace in Split, Croatia.

A gravure by Robert Adam, of the ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Split, Croatia. Public domain

In the past two decades, scholars have made significant progress in understanding Roman baths, shifting focus from grand baths in Rome to smaller-scale balnea, which were central to everyday life across the Empire. These studies highlight the importance of the hypocaust system, the revolutionary Roman invention that used an underfloor heating system supported by brick or stone pillars (pilae) to circulate hot air beneath elevated floors.

The hypocaust system typically connected the praefurnium (furnace) directly to the caldarium (hot room), ensuring the highest temperatures in this space. This proximity became a key feature in interpreting bath layouts. Additional indicators, such as room apertures regulating airflow, floor thickness, and architectural design, further aid in identifying the function of individual rooms like the tepidarium (warm room) and sudatorium (dry sauna).

The introduction of the hypocaust system not only improved living standards across Italy, but also transformed daily life in colder provinces.

The hypocaust system of the Roman baths of Berytus (modern Beirut). Credits: JossK from Getty Images, by Canva

However, while much is known about the design and function of balnea, the exact ambient conditions of rooms like the caldarium, tepidarium, or sudatorium remain elusive. Many theories and experiments over the past century have provided only partial insights, often focusing on private baths and yielding inconclusive results.

For instance, the famed baths of the imperial villa near Piazza Armerina in Sicily continue to generate debate about the actual temperatures achieved in their caldarium and sudatorium. Despite speculation and experimental reconstructions, questions about the thermal properties of Roman baths remain unanswered, emphasizing the need for further interdisciplinary research to fully understand the environmental and technological sophistication of these iconic structures. (Heating System in the Ancient Worls: The example of the Southwestern Balneum in Diocletian's Palace in Split, by Turkovic T., Bogdan Z., and Jurkovic M.)

Glazed Windows and Roman Innovation

The Forum Baths of Ostia, constructed in the early second century AD, featured large south-facing windows designed to capture sunlight throughout the day, particularly during popular bathing hours from early afternoon to evening. These windows, typical of Roman bath architecture across the Empire, played a key role in heating and lighting. One prominent room, identified as a warm tepidarium, has sparked debate among scholars regarding its heating efficiency and glazing.

E.D. Thatcher, argued in 1956 that radiant heat from the sun and heated surfaces could alone maintain a comfortable temperature for bathers, even without window glazing. He emphasized the ability of the hypocaust system, which heated floors, walls, and ceilings to high temperatures, to create sufficient radiant warmth.

However, Yegul, a Roman bath expert, has critiqued Thatcher’s claims as overly optimistic, pointing out that extensive evidence for glass and window frames in Roman baths suggests that glazing was a common and more energy-efficient solution. According to Yegul, unglazed windows would result in significant heat loss, making it economically impractical to maintain warmth in large open spaces, especially during cold winter months.

Additional insight comes from historians Jordan and Perlin, who discuss the increasing scarcity of timber by the first century BC. The Roman Empire’s heavy reliance on wood for bathhouse furnaces and growing industries led to steep rises in fuel costs, necessitating innovations like glazing to conserve energy.

They note that by the third century AD, Rome boasted over 800 baths, highlighting the logistical challenges of fuel consumption and heating efficiency.

The hypocaust system of a Roman bath. Credits: syolacan from Getty Images, by Canva

Thatcher’s hypothesis assumes that the heated surfaces of the tepidarium were maintained at approximately 100°F (±38°C), radiating sufficient warmth to offset the cold air from open windows.

However, experimental studies, such as those by Rook in England and Kretzschmer in Germany, indicate that even with hypocaust systems reaching temperatures of up to 400°F (±205°C), unglazed windows would lead to substantial heat loss. Modern studies on thermal comfort suggest that glazed windows would have provided a more balanced and sustainable environment for bathers, particularly during colder seasons.

While Thatcher admired the Romans' confidence in radiant heating, modern perspectives highlight the practicality of combining glazing with hypocaust technology. The debate underscores the ingenuity of Roman engineering and the ways in which they adapted their architectural designs to maximize comfort while managing resources efficiently. (Windows, Baths, and Solar Energy in the Roman Empire, by James W. Ring)

Sergius Orata and the Mystery of Roman Heating Innovations

Pliny the Elder offers the most detailed account of Sergius Orata, a curious figure in Roman history, whose entrepreneurial activities have sparked debates among scholars. While some suggest Orata invented the hypocaust, archaeological evidence disproves this claim, showing similar systems existed in Greece and Magna Graecia over a century before Orata's time. Instead, it has been proposed that Orata refined the technology or contributed a variation distinct from earlier Greek systems.

The central question revolves around the term pensiles balineae, translated as "hanging baths," attributed to Orata. Literary sources like Pliny and Cicero describe Orata as a wealthy fish farmer in Campania during the late Republic. Cicero refers to him as a man of comfort and business acumen, possibly linking the pensiles balineae to his ventures.

However, these sources provide limited insight into the exact nature of this invention, and no clear archaeological evidence has been found to support specific claims. Modern interpretations often equate pensiles balineae with hypocausted baths, as the term suspensura—used by Vitruvius to describe underfloor heating—resembles the description of Orata's invention.

Yet this identification is problematic. The terms suspensura or hypocaustum are conspicuously absent in discussions of Orata’s invention, and pensiles balineae are not directly associated with baths for human use. Some scholars propose an alternative explanation: that pensiles balineae were raised or terraced fishponds rather than bathhouses.

Orata was actually renowned for his expertise in fish farming, particularly oysters, which were highly prized by the Roman elite.

Freshly opened oysters. Credits: heinstirred from Getty Images Pro, by Canva

Terraced fishponds, possibly built above ground or cascading into one another, would align with Orata’s reputation as an innovator in aquaculture. Such structures might also explain the poetic use of the term pensiles, referring to their elevated or suspended appearance.

Further complicating matters, the physician Asclepiades of Bithynia is said to have adapted Orata’s pensiles balineae for medical purposes, introducing hot water to the system for therapeutic treatments. While this connection suggests a link to bathing, it is more likely that Asclepiades repurposed Orata’s invention rather than expanding its original function.

In summary, the widespread belief that Orata invented the hypocaust is unsupported by both literary and archaeological evidence. Instead, his pensiles balineae were likely connected to fish farming, with their application to human bathing appearing later and in limited contexts. This reinterpretation removes Orata from the developmental history of Roman baths, allowing a clearer understanding of the transition from Greek to Roman hypocaust systems. (Sergius Orata: Inventor of the Hypocaust?, by Garrett G. Fagan)

The “Indirizzo” Baths of Catania

The “Indirizzo” Baths in the historic center of Catania, Italy, are a fascinating example of Roman engineering ingenuity. Built over the underground Amenano River in a once-thriving commercial district, these baths date back to the 3rd or 4th century CE, though some scholars suggest they could be even older.

Their name and history are tied to the nearby church of Santa Maria dell’Indirizzo and the Carmelite Convent, which incorporated the baths into its structure, preserving them remarkably well over centuries. First excavated in 1779 by Prince Ignazio Paternò Castello, who identified its grand octagonal domed hall as a laconicum (sweat room), the baths remained largely hidden until restoration work in the 1930s.

Despite their excellent state of preservation, the site remains little-known and seldom visited. The baths followed a traditional Roman layout, with an apodyterium (changing room) leading to a frigidarium (cold room) and tepidaria (warm rooms), eventually reaching the central octagonal caldarium (hot room).

The design aligns with Vitruvius’ principles, placing cold rooms on the cooler north side and heated areas toward the south. Heat distribution relied on the hypocaust system, with brick pillars supporting raised floors and terracotta pipes embedded in walls to channel warmth.

Photo #1: Detail of the thermal architectural structure

Photo #2: Detail of the walls in squared lava stone blocks

Photo #3: Dome roof

The heating process was intricate, involving several stages:

- Wood-fired furnaces (praefurnia) produced heat.

- The heat was distributed horizontally through the hypocaust beneath the floors.

- The floors and baths were warmed by this heat, while hot water tanks were fed by cisterns.

- Warm air was directed vertically through hollow terracotta pipes (tubuli).

- Finally, flue gases were expelled through chimneys, ensuring efficient ventilation.

Though the baths’ original entrance and some features remain uncertain, studies and reconstructions provide valuable insight into the advanced thermal engineering of Roman society. The “Indirizzo” Baths exemplify how Romans combined functionality with architectural elegance, creating spaces for both hygiene and socialization. (Thermo-hygrometric behaviour of Roman thermal buildings: the “Indirizzo” Baths of Catania (Sicily), by A. Gagliano M. Liuzzo G. Margani W. Pettinato)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: