Gaius Caesar: The Lost Heir of Augustus

Gaius Caesar, grandson and adopted son of Augustus, was groomed as Rome’s imperial heir, showered with honors and entrusted with command in the East. His sudden death at twenty-three shattered Augustus’ dynastic hopes and reshaped the course of the empire.

Gaius Caesar, grandson and adopted son of Augustus, was once the brightest hope of Rome’s imperial future. Groomed from youth to inherit the mantle of the first emperor, he was celebrated with honors, statues, and offices far beyond his years.

Sent east to command legions and negotiate with kings, Gaius embodied the promise of dynastic continuity. Yet his dazzling rise ended in tragedy: wounded in Armenia and dead in Lycia at just twenty-three, he left Augustus’ careful plans in ruins and forced Rome to imagine a very different path for the empire.

Gaius and Lucius Caesar: Heirs of Augustus in Life, Death, and Image

In 23 BCE, only four years after establishing the Principate and ushering in a new era of peace following civil war, Augustus Caesar fell seriously ill and nearly died. Had he not recovered, Rome might have faced another destructive struggle for power. To prevent such chaos, a suitable and widely accepted heir was needed, ideally from Augustus’ own bloodline.

Yet Augustus had no sons of his own, and his nephew and son-in-law Marcellus—his closest male relative—died young soon after Augustus’ illness. Augustus’ only child, Julia, was then married to his trusted friend and lieutenant Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, and this marriage gave Augustus hope for heirs of his bloodline. Julia bore two sons: Gaius in 20 BCE and Lucius in 17 BCE.

In 17 BCE Augustus formally adopted both boys, despite their parents still being alive, thereby elevating their dynastic status. Yet succession in the Principate was not hereditary by default.

Augustus ruled as Princeps—First Citizen—not as monarch, and his position was grounded in a unique concentration of powers he himself had earned. For Gaius and Lucius to succeed him, they needed political offices, military commands, and personal prestige.

Augustus ensured they were advanced early, granted extraordinary honors, and pushed into public life. Despite this preparation, both died tragically young—Lucius at about eighteen in 2 CE, and Gaius at about twenty-three in 4 CE—shattering Augustus’ dynastic hopes.

Their importance to Augustus’ political plans was mirrored in their imagery. In a largely illiterate empire, portraits were powerful tools of communication. Sculptural statues, busts, reliefs, coins, and gems depicting Gaius and Lucius circulated widely. Their images symbolized dynastic unity and political stability, reinforcing confidence in Augustus’ regime.

Official portrait prototypes, likely distributed in terracotta or plaster, allowed their likenesses to be replicated across the empire. Though dissemination was not strictly controlled by the state, local communities enthusiastically honored the imperial family, driven by competition and a desire to display loyalty.

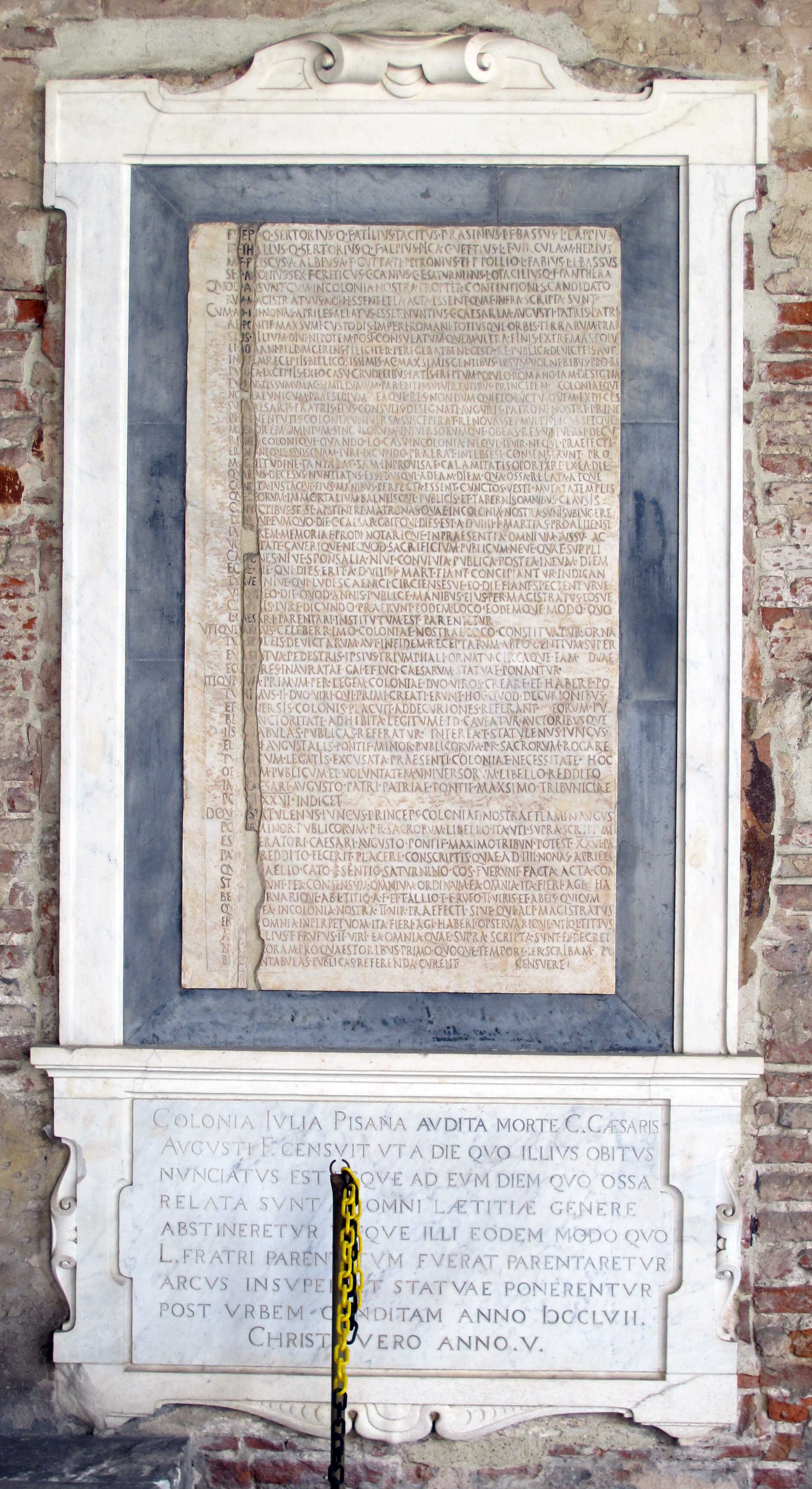

Literary, numismatic, epigraphic, and sculptural evidence demonstrates the success of Augustus’ program: Gaius and Lucius enjoyed immense popularity during their lives and even after their deaths, while Augustus was still alive. Portraits and inscriptions honoring them appear across the empire. Interest waned after Augustus’ death in 14 CE, though traces remain in the Tiberian period.

Inscriptions from Spello, for instance, record annual celebrations of Gaius, Lucius, and Drusus Maior on their burial anniversaries. One inscription from Iesi commemorates Lucius as patron of the town. These gestures may have been encouraged by Tiberius to strengthen the notion of hereditary succession and validate his own position.

Most coins bearing their images date to Augustus’ reign, but at least one bronze issue from Pergamon appears to belong to the Tiberian period, likely reflecting local loyalty. Nonetheless, the overwhelming majority of portraits were produced under Augustus, with very few after.

Some later depictions may have arisen from local affection or special benefactions granted by Gaius, who traveled extensively in the East between 2 BCE and 4 CE. Their premature deaths enhanced their aura; as with many figures cut down in youth, their memory lingered even after dynastic hopes shifted.

Identifying their portraits, however, has long been one of the most vexing challenges in Roman art history. No inscribed statues of either youth survive, and coin portraits are of limited use for establishing their features. Ancient literary descriptions are scant: the late writer Macrobius claimed Agrippa’s children by Julia resembled their father, though this may have been intended to quell rumors about Julia’s behavior or the legitimacy of her sons.

Portraits are further complicated by the tendency toward idealization, strong family resemblances, and deliberate assimilation of features across the Julio-Claudian line. Portraits of Gaius have often been confused with those of the young Octavian.

Despite these difficulties, advances in the study of Augustan portraiture have allowed scholars to exclude other family members and to define several portrait “types” for Gaius and Lucius, each linked to stages in their lives. Yet caution is needed: over-identification based on superficial similarities remains a risk.

Even so, the weight of evidence now makes it possible to identify and differentiate their portraits with greater confidence, while acknowledging the challenges posed by their idealized youthfulness, political assimilation, and the fragmentary nature of the surviving record. (The portraiture of Gaius and Lucius Caesar, by John Pollini)

Balancing Act: Augustus’ Succession Between Family and State

For a long time, it’s been assumed Augustus always meant to found a dynasty and groom a blood heir from the start. Augustus had a problem to solve—how to keep his personal leadership continuous for stability without looking like he was creating a hereditary monarchy when there was no “office” to pass on. His answer, was to act as princeps (first citizen), not to proclaim a principatus (an explicit, heritable kingship).

That’s only half the story. Like any Roman noble, Augustus also wanted to pass on a family made powerful enough that its next head would naturally dominate public life. The Julian household’s resources—money, clients, troops’ loyalty, and a cadre of top generals—were so vast that “family planning” inevitably had state consequences.

In practice, the familia Caesaris and the machinery of government blurred: imperial slaves kept “state” records, paid contractors and soldiers, staged festivals, and the legions’ allegiance to the House of Caesar underwrote the whole system. In that world, arranging inheritance inside the domus was already de facto state succession.

Publicly, Augustus wrapped this reality in the language of law, tradition, and finite mandates. He highlighted auctoritas (moral influence) over potestas (formal powers) and accepted honors that looked “republican,” even as the effect was to normalize one-man predominance.

Modern accounts often imagine him relentlessly encroaching on old liberties; but support for Julian leadership was broad and persistent—senators, equestrians, and ordinary Romans could see the bargain: external victories and internal peace instead of renewed civil war. Pressure did not flow only from Augustus onto society; it also came up from allies and stakeholders who wanted clear continuity at the top.

From early on, dynasty and autocracy developed together. Augustus initially refused the charged title Pater/Parens Patriae in 27 BCE, but he steadily advanced his family as the state’s unifying symbol. Two tactics mattered most: endogamous marriages and bloodline priority. With no son by Livia, Augustus knit the leading branches together—first through Marcellus, then decisively through Agrippa and Julia—and, crucially, through adopting his grandsons Gaius and Lucius as infants.

That unprecedented move both advertised blood descent and tightened the political unity of the house. Alongside maius imperium, Augustus showcased tribunician power—renewable, personal, and not tied to holding the tribunate itself. Granting versions of these powers to Agrippa (and later to Tiberius) marked out senior partners without declaring a monarchy.

Religion and urban ritual were harnessed to the same end. After Lepidus’ death, Augustus became pontifex maximus amid a huge show of consensus; his household cult fused with Rome’s oldest sacra (Aeneas’ Palladium and penates), making the head of the Julian family the natural father of state worship. At the neighborhood shrines, Romans began honoring the Lares Augusti and Genius Augusti, effectively recasting local religion in familial terms: the city’s people related to the princeps as dependents to a household head.

Architecture and ceremony made the message legible—the Ara Pacis processions balancing Senate and imperial family; the Forum of Augustus linking Aeneas, Julius Caesar, and Augustus as Pater Patriae; and the carefully staged toga-virilis rites that named Gaius and Lucius principes iuventutis, generational mirrors to Augustus’ princeps senatus.

Tiberius’ role tracks these shifts. After Agrippa’s death, Augustus folded him into the succession strategy (marriage to Julia; later, tribunician power and maius imperium), broadly echoing Agrippa’s earlier position as senior guarantor until the princes came of age. His sudden withdrawal to Rhodes likely reflects the rising heat of overtly dynastic politics rather than surprise at Gaius’ and Lucius’ advancement. Meanwhile, the senate and provinces began swearing oaths that named the young Caesars alongside Augustus—public confirmation that continuity was expected from within the house.

The culmination came in 2 BCE, when Augustus finally accepted Pater Patriae—not a random flourish, but the capstone of years of sacral, civic, and familial alignment. That settled the ideology: the state’s father would be followed, in Roman fashion, by a son. Then fate intervened. Lucius (2 CE) and Gaius (4 CE) died young, and the carefully staged plan collapsed.

Augustus salvaged continuity by adopting Tiberius (and making him adopt Germanicus), renewed his tribunician power, and granted him imperium maius. Dedications like the Temple of Concordia Augusta advertised unity between domus and res publica; by 14 CE the transition was smooth enough to show how far attitudes had moved. The Principate—heritable in practice, if not by statute—had arrived. (The Succession Planning of Augustus, by Tom Stevenson)

Image #1: The outside remains of the cenotaph of Gaius Caesar in Limyra. Credits: Das Robert, CC BY-SA 3.0. Image #2: An impressive marble procession found in Gaius Caesar’s Cenotaph, in Limyra. Credits: Troels Myrup, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Gaius in the Historians: From Augustan Hope to Tiberian Foil

The most detailed near-contemporary portrait of Gaius Caesar comes from Velleius Paterculus, writing in AD 30. As a soldier who had served under Gaius in the East, Velleius was an eyewitness to parts of his career. Yet his account is shaped by loyalty to Tiberius, under whom he later thrived.

His narrative paints Gaius as impulsive, vulnerable to bad advisers, and ultimately ineffective after being wounded. The result is what one scholar has called the image of an “ideal non-princeps”—a figure whose shortcomings served to cast Tiberius’ prudence in a brighter light.

The Eastern Mission and Its Silences

Between 1 BCE and 4 CE, Gaius held supreme command in the East, a role that climaxed with his celebrated meeting on the Euphrates with the Parthian king Phraataces. Velleius recalled the event as a moment of immense prestige for Rome, but he passed over Gaius’ concrete military achievements.

Inscriptions, however, record victories in Arabia and Armenia, evidence of successes that Velleius deliberately suppressed. His silence was a rhetorical strategy: by minimizing Gaius’ accomplishments, he reinforced the idea that only Tiberius embodied the qualities of a true leader.

Other ancient writers add further perspectives. Cassius Dio depicted Gaius as spoiled by luxury and insolence, suggesting Augustus dispatched him East to temper the reckless ambition of the young Caesars. Josephus, by contrast, stresses that Gaius was already seasoned in diplomacy at Rome before his mission, presenting him as less naive than Velleius allowed. And Augustus himself, in the Res Gestae, memorialized his grandsons with poignant words:

“my sons, whom Fortune tore from me while still young”

—a sharp reminder of the central place Gaius and Lucius once held in dynastic hopes.

Wound, Withdrawal, and Death

Gaius’ decline began in Armenia in AD 3, when he was ambushed near Artagira and gravely wounded. Ancient sources agree that the injury broke him both physically and mentally. Rather than return to Rome, he lingered in the remote provinces, eventually dying in Lycia in 4 CE. This retreat fed the later narrative of a failed prince—once the brightest hope of Augustus, but ultimately unfit to shoulder the burdens of empire.

The way Gaius was remembered reveals as much about Tiberian Rome as about the man himself. By the time Velleius wrote, Julia the Elder’s line—Gaius, Lucius, and Agrippa Postumus—had vanished or been disgraced. Livia’s line, embodied in Tiberius, stood ascendant.

To support the legitimacy of the ruling emperor, Gaius’ memory was reshaped: monuments and inscriptions had once exalted him, but historiography turned him into a foil, a reminder of promise unfulfilled. His story thus reflects not only personal tragedy but also the political stakes of dynastic memory in the early empire. (Gaius Caesar, or the ideal non-princeps: a Tiberian issue, by Antonio Pistellato)

In Gaius Caesar, Augustus glimpsed the future of his dynasty—only for Fortune to snatch it away, leaving Rome to mourn its lost heir.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: