Convivium: How the Romans Turned Dinner into a Display of Power

They didn’t just dine—they performed. The Roman convivium was a spectacle of power, where food, posture, and even the furniture spoke volumes about wealth, status, and control. To eat was to assert who you were—and who you weren’t.

They came not just to eat, but to witness and be witnessed. In the Roman world, the convivium was no ordinary dinner—it was a carefully orchestrated spectacle of wealth, culture, and control. Reclining on couches beneath frescoed ceilings, Rome’s elite dined in style while asserting their place in the social hierarchy.

Food became performance, tableware a tool of domination, and the very layout of the dining room a statement of power. To understand the convivium is to unlock a key ritual of Roman identity—where every bite, every glance, and every guest list spoke volumes.

What the Roman Convivium really looked like

When most people think of Roman dining, the imagination tends to run wild—images of outlandish delicacies, indulgent banquets, lounging elites, bouts of vomiting, and, inevitably, a descent into orgy.

An informal poll of Karen M. Spence’s own circle (an engineer that holds a graduate degree in Classical Mediterranean Archaeology from the University of Leicester, UK), confirmed just how deeply these clichés are embedded, with predictable references to dormice and extravagant birds stuffed with other animals. But Roman dining, like many aspects of the ancient world, has long suffered from the seductive power of sensationalism.

To get closer to the truth, we have to examine the convivium—the communal Roman dining experience—by drawing on various forms of evidence across the empire, not just to reconstruct the events themselves, but to expose how such evidence has often distorted our understanding.

At first glance, piecing together what Roman dinner parties actually looked like—their form, purpose, and culinary preferences—is a challenge. The architecture of supposed dining rooms, material remains, and textual sources rarely align neatly.

Scholars seeking a consistent picture are bound to be disappointed. Yet these sources remain crucial for situating Roman dining behavior in context. As anthropologist Sidney Mintz once put it,

“food and eating afford us a remarkable arena in which to watch how the human species invests a basic activity with social meaning”

—a reminder to look beyond surface impressions for deeper insights.

We need to focus specifically on elite private dining, leaving aside imperial banquets and non-elite practices. The wealthy classes, after all, were the ones with access to food in excess of subsistence and the means to shape dining into a cultural performance.

Because most of our evidence—both literary and archaeological—comes from elite contexts, the picture we have is necessarily narrow and socially skewed. This is a broader issue in Roman archaeology, but one worth confronting. By analyzing dining practices from various regions of the empire and highlighting scholarly missteps that have led to false generalizations, we can offer a more grounded view of what the Roman convivium actually entailed.

Reclining in Style: The Roman Convivium and the Spaces that shaped it

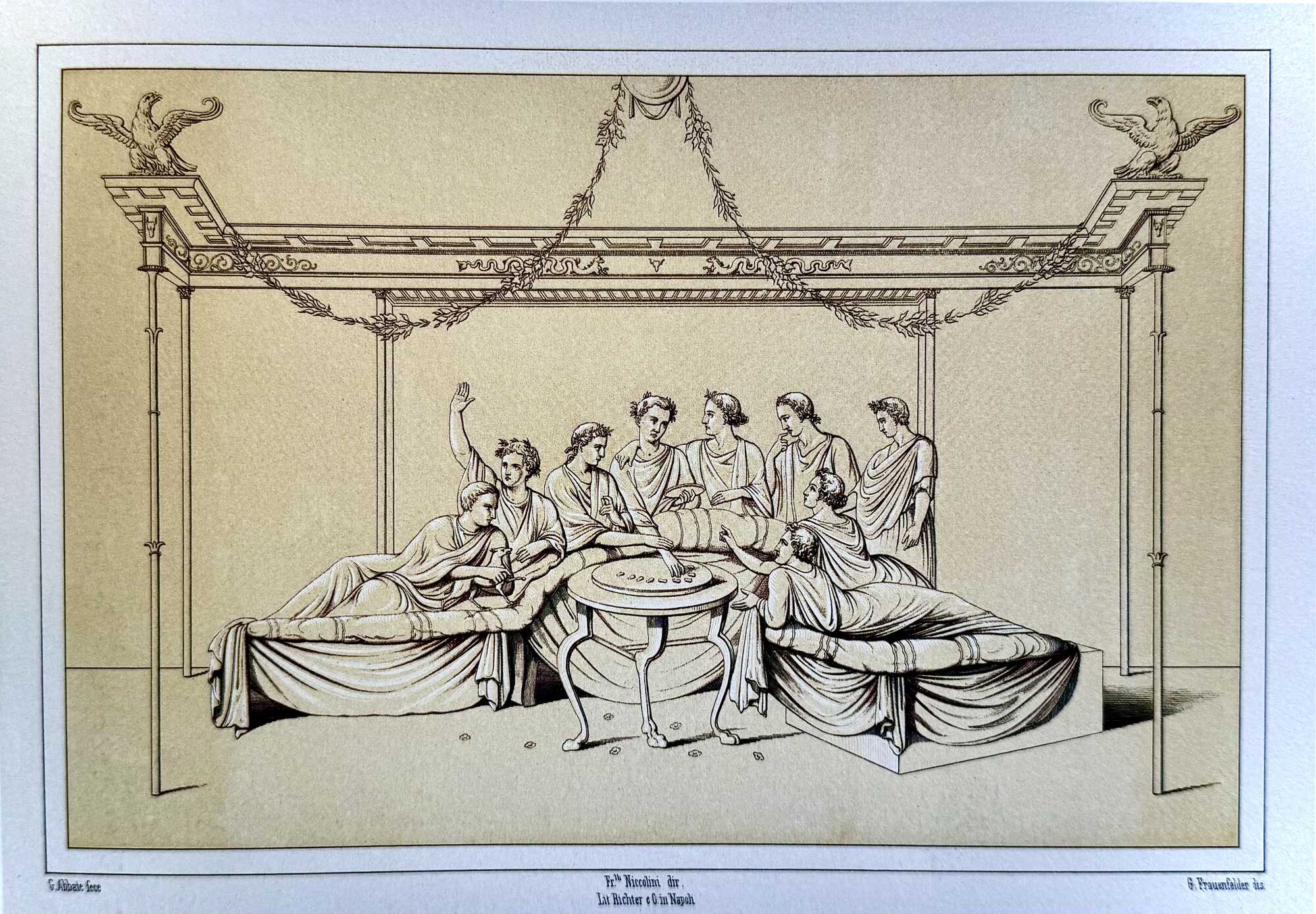

Furniture and tableware provide some of the clearest traces of Roman dining, offering valuable insight into where and how food consumption likely occurred. A typical Roman dining room often featured a layout designed for reclining guests.

Three wide couches were arranged in a U-shape around a central table—usually square or round—placed directly on decorative mosaics. These dining areas were frequently oriented toward a garden, creating an elegant visual connection between architecture and nature. The couches, known as lecti, could be either built into the room’s structure or brought in as movable pieces.

Public domain. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

The ideal number of guests appears to have been nine—perhaps in homage to the nine Muses—a notion supported by wall paintings and the dimensions of surviving couches. In practice, though, guest numbers could range from three to nine, and such figures don’t account for those who might have sat on chairs, the floor, or even stood during the gathering.

The trio of couches is often collectively referred to as the triclinium, a term that originally described the couches themselves, not the room. Yet over time, it became common—even in scholarly discussions—to use the word to refer to the dining space as a whole, despite the fact that not all Roman homes had the furnishings typically associated with this setup.

Evidence from domestic spaces—especially rooms adjacent to or opening onto gardens—shows that these were common places for dining furniture to be located. Similar arrangements have been found outside of Italy, including in eastern parts of the empire, such as in Patras, Greece.

While this spatial design represents a widespread model of elite Roman dining rooms, it coexisted with older architectural styles. In many regions, traditional Greek features like the classical andron or Hellenistic oecus remained in use well into the Roman period, even if they had fallen out of architectural fashion.

The spread of Roman-style dining spaces did not necessarily signal the wholesale adoption of Roman dining customs. The presence of a triclinium-like arrangement does not guarantee that the social protocols and meanings associated with Roman dining were fully embraced elsewhere.

Within Roman homes themselves, dining was not always confined to formally designated rooms. Movable furniture allowed for flexibility, and in many cases, meals might have taken place on beds or couches normally used for sleeping.

Even among households with the means to host guests, the specific layout of a home could dictate where shared meals could realistically occur. The material remains remind us that, while ideals existed, dining practices were shaped just as much by architectural limitations as by cultural aspirations.

Painted Feasts: Art, Illusion, and the Meaning of the Roman Convivium

Wall paintings and mosaics found in Roman dining spaces offer vibrant glimpses into the visual culture surrounding the convivium. Yet, like literary texts, they are not direct records of real events.

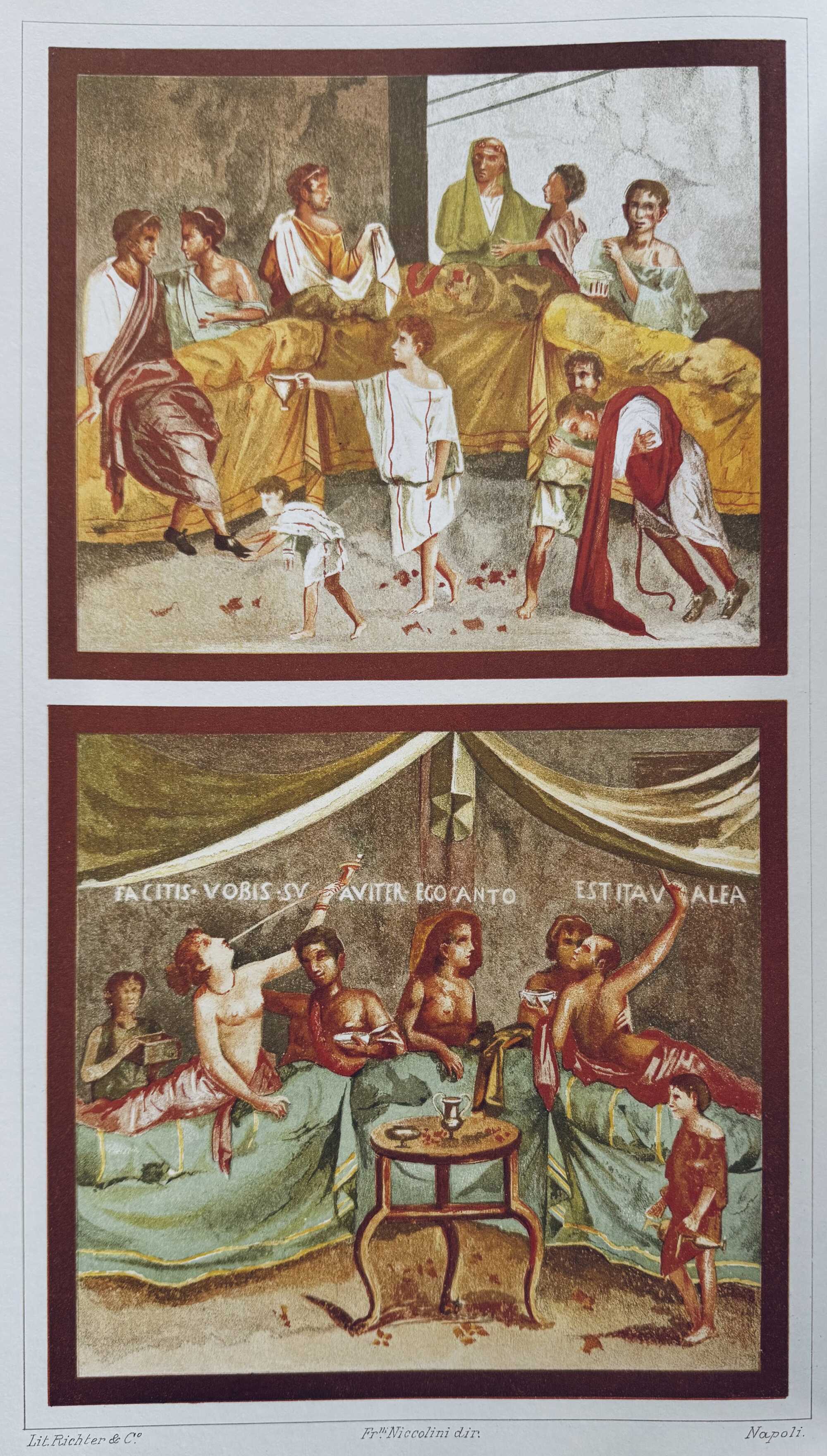

Many banquet scenes reflect artistic conventions rather than literal documentation of dining practices. Early Roman imagery, particularly from Pompeii and Herculaneum, often drew heavily from earlier Greek symposia traditions, adapting the visual language to suit Roman values and tastes. This connection opens up deeper questions about how the convivium was understood and differentiated from its Greek predecessor.

To the Roman mind, the convivium held a broader and more communal meaning than the symposium, at least ideally. It implied not merely the act of drinking together, but a shared experience of living and social bonding.

However, Roman dining customs departed significantly from the Greek model. Women, for example, had a limited but sanctioned presence at Roman dinner parties—something unthinkable at Greek symposia, where female attendees were usually slaves or entertainers.

Despite some philosophical idealizations of equality among guests, the Roman convivium was marked by distinct hierarchies, often reflected in seating arrangements and access to food and wine. These differences complicate the idea that the convivium was simply a Roman variant of the symposium.

Wall paintings from Pompeian homes allow us to explore this tension between aspiration and reality. In one example, the so-called House of the Chaste Lovers, the dining room displays banquet scenes in the decorative Third Style: red panels framed in black featuring couples reclining on couches, surrounded by drinking vessels and servants.

Image #2: Pompeii. February 2017.

Image #3: North wall of the House of the Chaste Lovers.

Photo courtesy of Parco Archeologico di Pompei. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

The setting varies between indoor and outdoor locations, and though couches and tableware are clearly represented, food itself is notably absent. This dining room followed a decorative format repeated in many homes, suggesting the use of visual pattern books and standard iconography. In fact, near-identical scenes are found in multiple houses across Pompeii, with minor alterations.

Whether these rooms were meant for private use or available for rent is difficult to determine. Evidence does exist that some triclinia could be hired for events—inscriptions advertising dining rooms with couches for rent confirm this practice.

But the art on the walls does not always align with the layout or function of the space. While the ideal triclinium arrangement of three couches in a U-shape appears in painted scenes, its physical presence in architecture is less consistent. These early representations focus not on showcasing material abundance, but rather on evoking an atmosphere of festivity and cultural refinement, inspired by Hellenistic traditions.

Another example, the House of the Triclinium, reflects this same dynamic. Although the banquet scenes have been updated to include Roman hairstyles and clothing, they still rely on Greek visual models and omit any direct portrayal of food.

These scenes celebrate the convivial spirit of the occasion rather than document its material aspects. Their nostalgic tone suggests a Roman admiration for the pre-conquest cultural past of Greece, subtly reinforcing the notion that contemporary Greece, while still culturally resonant, was seen as subordinate to Roman authority.

As time progressed, banquet imagery evolved to become more grounded in the realities of Roman dining. Later mosaics and paintings began to depict recognizable architectural features and actual food consumption. One playful and widely copied motif was the asarotos oikos, or "unswept house," first seen in a mosaic from Pergamum in the second century BCE. Scattered food debris rendered in mosaic gave the impression of a feast just finished, and variations of this theme appeared in homes throughout the Roman world, including Italy and North Africa.

By the third and fourth centuries CE, Roman banquet scenes had become far more literal. A mosaic from the House of the Buffet Supper in Antioch depicts a full, elaborate meal—complete with courses and silver serving dishes—arranged in harmony with the curved sigma couch that had by then replaced the traditional triclinium setup.

Photo courtesy of Antakya Archaeology Museum, Turkey. Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Elsewhere, a large dining room in Rome from the early Constantinian period features life-sized female attendants bearing trays of meats, vegetables, and wine, visually emphasizing abundance and display. This shift in imagery—from symbolic or idealized to representational and specific—offers a closer reflection of actual convivium practices and aligns more closely with written accounts of elite Roman dining.

Power on a Platter: Luxury, Imports, and Excess

One of the clearest expressions of class distinction in the Roman world appeared at the dinner table. Culinary privilege was reserved for the elite, who had not only the wealth but also the logistical power to access exotic ingredients. Calls for restraint were common among moralists of the Late Republic, who criticized indulgence and praised simpler times. Yet these appeals were often rhetorical.

As material evidence and literary accounts reveal, elite Romans indulged in theatrical feasts—fueled by the expanding spice trade and sophisticated cookbooks like those attributed to Apicius, which helped transform the kitchen into a stage of creative excess.

Although some writers idealized the convivium as a gathering of friendship and philosophical exchange, the food served—and the manner in which it was presented—told another story. Horace, for instance, describes a dinner he attended that involved elaborate preparations, rare ingredients, and a host eager to impress with culinary flair:

A lamprey now appears, a sprawling fish,

With shrimps about it swimming in the dish.

Whereon our host remarks: "This fish was caught

While pregnant: after spawning it is naught.

We make our sauce with oil, of the best strain

Venafrum yields, and caviare from Spain,

Pour in Italian wine, five years in tun,

While yet 'tis boiling; when the boiling's done,

Chian suits best of all; white pepper add,

And vinegar, from Lesbian wine turned bad.

Rockets and elecampanes with this mess

To boil, is my invention, I profess:

To put sea-urchins in, unwashed as caught,

'Stead of made pickle, was Curtillus' thought."

Horace, Satires 2.8.42–55

Such performances of taste were not without their dark side. In some cases, the pursuit of culinary novelty resulted in acts of brutality. One ancient source recounts the preparation of sow’s udders, made more flavorful by ensuring the animal’s litter was violently aborted just before birth—combining blood and milk to intensify the taste.

Imports of food, wine, and spices were vast. Out of the nearly 500 recipes preserved in the Apicius collection—augmented and circulated well into late antiquity—almost all require spices, and several call for ingredients sourced from as far as South or Southeast Asia.

The material record corroborates this, with amphorae and storage vessels found across the empire pointing to robust and far-reaching trade networks. Rome’s ability to move these goods speaks to the administrative strength of its empire—but also to the imbalance it created between producer and consumer.

A well-known episode underscores the symbolism embedded in such feasting. Emperor Vitellius, dining at his brother’s home, had his generals compile a massive dish featuring food sourced from every corner of the empire—from Parthia to the Atlantic coast of Spain. He devoured it in its entirety, an act that simultaneously flaunted personal excess and Roman dominion.

Even so, Rome never pursued culinary imperialism. Provincial diets remained distinct, and Rome did not enforce a standard cuisine to unify the empire. In fact, elite Roman anxieties about imported luxuries and moral decay often pointed to the East as the source of decadence.

Some authors traced the rise of greed and moral decline in Roman society to the aftermath of Eastern conquests, which introduced new luxuries and foreign values. Beneath the moralizing tone, there lingered a deeper fear: that Roman identity itself could be altered by what others brought to the table.

To label the convivium as merely gluttonous is to miss its deeper purpose. These elaborate feasts were structured social performances. Hosts displayed their power not only through what was served but how it was served.

Portions, placements, and the quality of tableware were all tools for reinforcing rank and authority—making the Roman dining room a theater of status as much as a space of indulgence.

Equal Guests or Displayed Rank?

Pliny the Younger once recounted a telling exchange at a dinner party. He explained that when he hosted guests, he made no distinction in what each person was served, regardless of their social status. One of the other guests seemed surprised and asked,

“Even the freedmen?”

Pliny answered,

“Of course, for then they are my fellow-diners, not freedmen.”

That this response caused surprise reveals something deeper: the notion of egalitarian dining was the exception, not the rule. What people claimed to value and how they actually behaved often diverged.

In most cases, the convivium mirrored the host’s social standing and ambition. Invitations could elevate a host’s prestige—or reinforce their dominance over others. A graffito from Pompeii drives this home with blunt clarity:

“The man with whom I do not dine is a barbarian to me.”

The Roman house itself, with its architecture deliberately designed to reflect social hierarchies, reminds us that the idea of all diners being equals was far removed from reality.

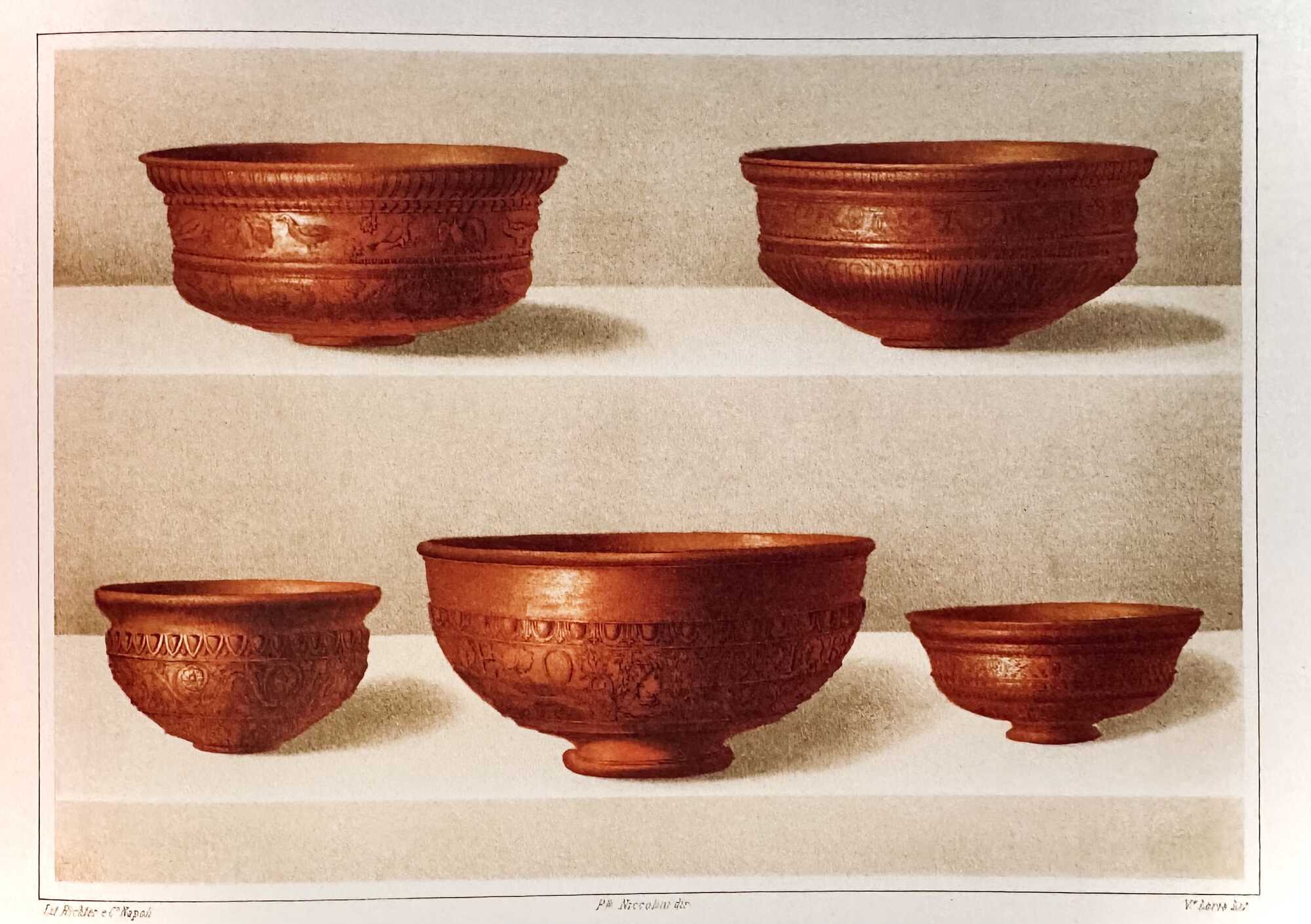

Terra sigillata ceramic wares decorated with reliefs. Credits: Fausto & Felice Niccolini. Houses and Monuments of Pompeii by TASCHEN, Photo by Roman Empire Times

At the convivium, social rank could be expressed in various ways. Two main dining traditions existed. One featured equal, individual portions served to each guest. The other relied on shared dishes placed centrally for all to draw from.

These approaches were not just a matter of logistics—they were laced with expectation and tension, especially since dinner invitations were typically reciprocal. Individual servings allowed the host to control both the amount and quality of food each person received.

This created space for subtle affronts, as Pliny experienced when he found himself at a dinner where different wines and vessels were used for different guests. He scathingly likened the entire affair to an “auction.” The philosophical appeal of shared service lingered, however.

Though individual portions had become common by the second century, some still viewed communal eating as more generous and egalitarian. The shared dish suggested friendship and togetherness, while the individual plate risked emphasizing inequality. Archaeological evidence sheds light on how these dynamics played out in practice.

An analysis of dining assemblages across the empire looked at bowls, plates, and platters to distinguish between personal and communal use. Sets of small, matching vessels were often tied to individual service. By studying their dimensions—especially rim size and volume—researchers could infer whether a dish was likely meant for a single diner or for shared access.

A sample of twelve sealed assemblages was analyzed, ranging from the early first century in Corinth to the early seventh century in Alexandria. The early examples showed a preference for coordinated, individual dining sets. In contrast, later assemblages reflected more mixed forms—large serving dishes accompanied by smaller, non-matching bowls. The trend suggested a structural change in the Roman convivium, shifting gradually from individual service toward shared meals.

Although a broader sample size would have strengthened the findings, the available data points to a notable transition. The shift is particularly interesting given how artistic depictions did not always align with this change. Early imperial banquet art often emphasized symposium-style drinking and idealized conviviality, despite the archaeological pattern favoring individualized servings. Later imagery, on the other hand, featured more shared dining scenes—especially in Christian and funerary contexts.

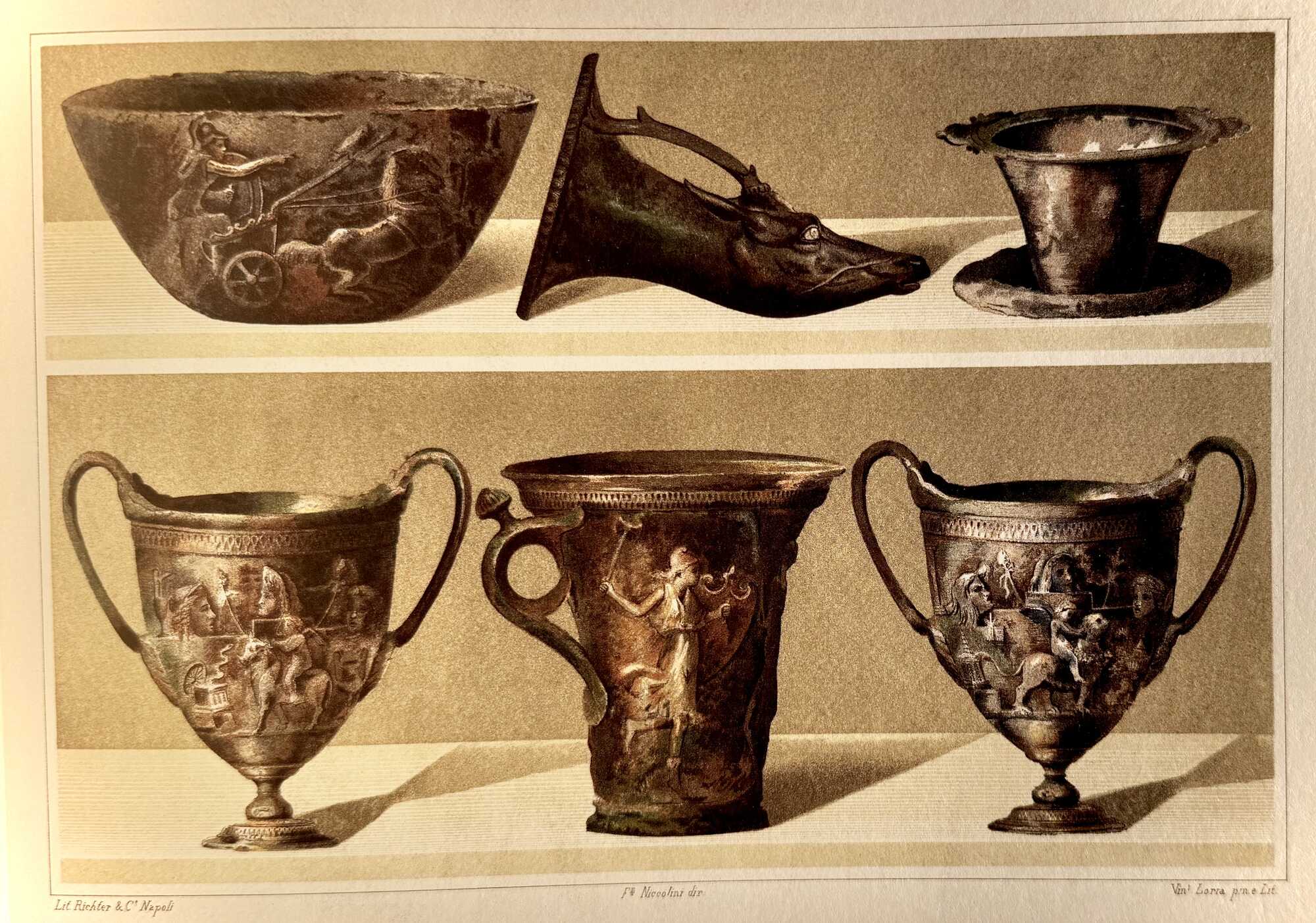

(B): Bronze drinking vessel in the shape of a stag's head (rhyton) from Herculaneum.

(C): Silver sieve and saucer.

(D) and (F): Two silver cups with handles (kantharoi) from a 64-part service from the Casa di Inaco e lo (VI 7,19). Winged erotes ride on a bull (left) and a panther (right), with various objects associated with Dionysus behind.

(E): Silver beaker with handle (kalathos) with a representation of the battle between Theseus and the Amazons.

Some have argued that these images of communal banquets reflected real shifts in elite dining culture, influenced by religious traditions of group meals. However, it’s difficult to accept this link entirely. The shared dining scenes that appear in catacombs—Christian and pagan alike—are deeply symbolic. It’s unlikely they accurately represent private elite meals.

Funerary iconography served its own purpose, separate from domestic reality. While religion may shape societal values, images tied to cult practices are not reliable indicators of everyday elite behavior, even when religion is culturally dominant.

This reinforces a broader point: values and practices are not always aligned. Though shared dining is often idealized as fostering community, the social effects may have been overstated. The practicalities of late imperial life offer another explanation. As resources dwindled—whether financial, agricultural, or logistical—it became easier and more economical to present food for communal consumption.

A single set of dishes, laid out to appear abundant, could impress guests while placing limits on their consumption. Individual portions required more planning, more utensils, and often more food. Serving from a central dish may even have helped avoid second servings—making it both efficient and visually lavish.

It’s also possible that sumptuary laws played a role in this evolution, though there’s no clear measure of how effective such regulations were in curbing excess. Ultimately, this isn't to dismiss the social dimensions of the convivium but to suggest that the economic aspect of dining deserves more attention. What appears as a gesture of communal generosity may just as well have been a smart way to stretch declining resources. (Haute Cuisine, Conspicuous Consumption and Power Play around the Triclinium: Analysis of the Roman Convivium, by Karen M. Spence)

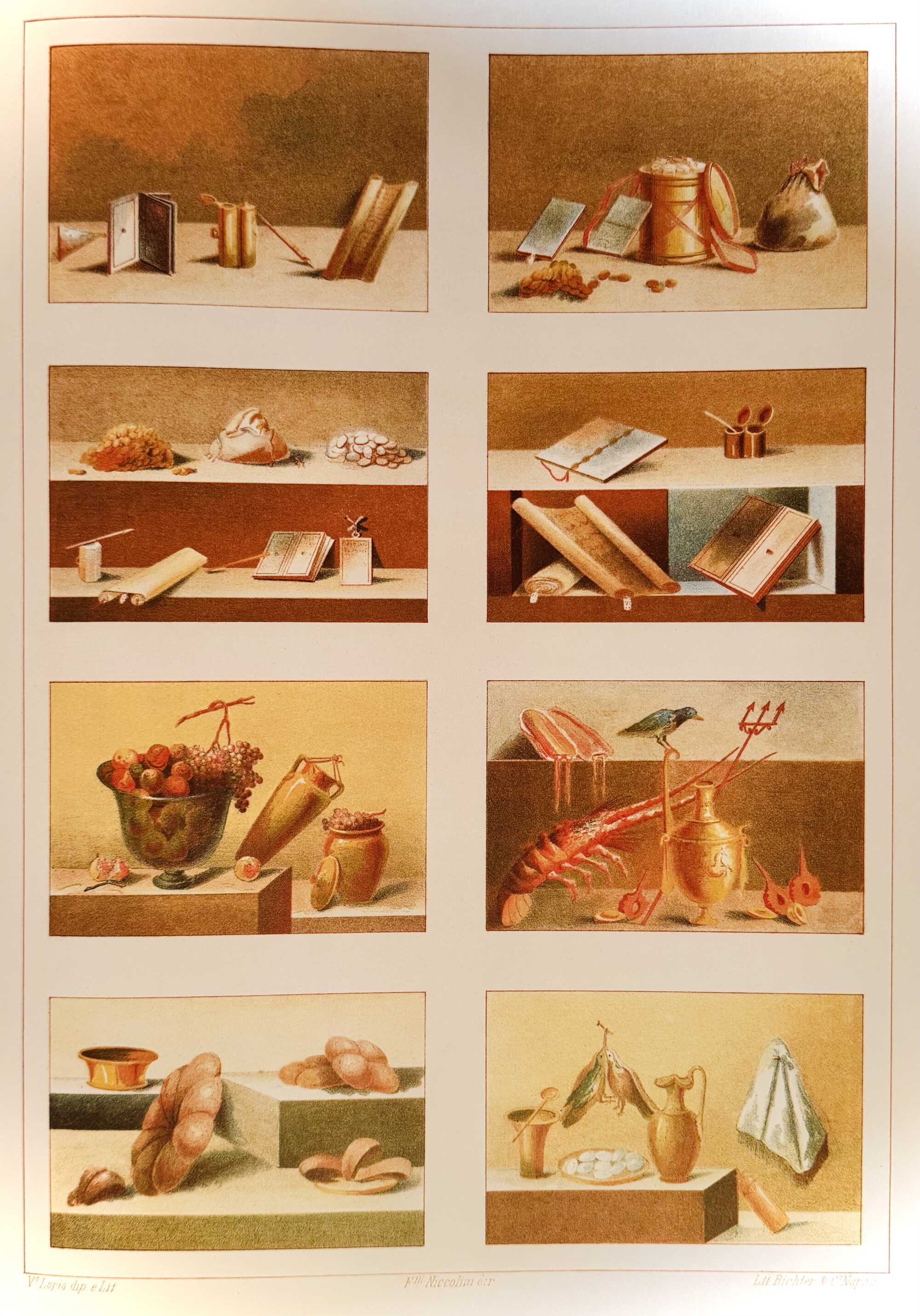

Below: still lifes of foodstuffs from the Macellum, where they appear in the upper zone of painting above the mythological themes, in fitting allusion to the building's function.

Women at the Table: Reclining, Respectability, and the Gender Politics of the Convivium

Unlike the Greek symposium, where the presence of respectable women was almost unthinkable, the Roman convivium allowed elite women to join their male counterparts in reclining at dinner. But this apparent inclusion was far from straightforward. In Roman society, posture was never neutral—it was loaded with cultural meaning. To recline was to declare oneself a full participant in elite leisure, a statement traditionally reserved for free Roman men.

When women took on this posture, they were not just sharing a meal—they were making a claim to status, legitimacy, and visibility within the domestic sphere. The shift toward allowing elite women to recline reflected broader Roman transformations. Rome inherited many dining customs from the Hellenistic East, but adapted them in ways that reinforced its own social order.

In doing so, it created a new model of domestic display: one that included high-status women not as silent observers, but as visible, reclining figures—a role that walked a fine line between dignity and suspicion. Art and literature of the period reveal this tension. Reclining women appear in wall paintings and banquet scenes, but they are often visually indistinct from courtesans, blurring the line between the respectable matrona and the sexualized meretrix.

This ambiguity was deliberate, and it fed Roman anxieties about gender, morality, and the influence of luxury. The sight of a woman reclining could be read as an assertion of elite Roman identity—or as a sign of creeping decadence. Within the triclinium, posture was performance. Who reclined, who sat, and who served were all part of a visual language that expressed hierarchy, gender roles, and moral values.

When elite women took their place among male diners, their presence was both empowering and provocative. It reflected the evolving social ambitions of the Roman aristocracy—where even dinner was a form of political theater. (Horizontal women: posture and sex in the Roman convivium, by Matthew Roller)

In the end, the convivium was far more than a meal—it was a microcosm of Roman society itself, where every posture, portion, and performance reflected the unspoken rules of status, gender, and imperial ambition.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: