Constantine’s Arch Damaged by Lightning: Are Monuments Ready for Climate Change?

The Arch of Constantine was damaged by a lightning strike, raising concerns about how well ancient monuments are prepared for climate disasters.

The Arch of Constantine, one of the most iconic monuments in Rome, suffered structural damage after being struck by lightning during a violent storm on September 3, 2024.

This ancient arch, which has stood for centuries as a symbol of Roman triumph, is now a testament to the growing threat that climate disasters pose to historical sites around the world. As climate change continues to intensify, with storms, floods, and wildfires increasing in both frequency and severity, the question arises: how well are our historical monuments prepared for the impact of such natural disasters?

Lightning Strike Damages Iconic Roman Arch

On the evening of September 3, a violent thunderstorm swept through Rome, bringing torrential rain, powerful winds, and frequent lightning strikes. One of these strikes hit the Arch of Constantine, causing visible damage to the ancient structure. The strike dislodged several stones and weakened parts of the arch’s foundation, prompting authorities to cordon off the area and conduct an immediate assessment of the damage.

According to local reports, the lightning struck the upper section of the arch, affecting the decorative reliefs and structural stones. Although no casualties were reported, the incident has raised concerns about the resilience of historical monuments in the face of increasingly extreme weather events.

Rome's Civil Protection Department was quick to respond, stating that they are currently working with preservation experts to assess the extent of the damage and implement necessary repairs. "The Arch of Constantine has stood for nearly two millennia, but modern climate events present new challenges that require swift action to protect it," said a spokesperson from the department.

What Is the Arch of Constantine, and Why Is It Important?

The Arch of Constantine is a triumphal arch erected in 315 AD to commemorate Emperor Constantine’s victory over Maxentius at the Battle of Milvian Bridge. Standing between the Colosseum and the Palatine Hill, the arch is a monumental symbol of Constantine's consolidation of power and his subsequent adoption of Christianity as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire.

It is the largest surviving triumphal arch in Rome and one of the most important landmarks of ancient Roman architecture.

Credits: Roman Empire Times

Constructed from massive blocks of white marble and adorned with intricate reliefs depicting scenes of Constantine’s victory, the arch represents the height of Roman imperial art and architecture. The monument combines original elements with spolia, or reused sculptures, from earlier emperors such as Hadrian, Trajan, and Marcus Aurelius, making it not only a tribute to Constantine but also a historical collage of Rome’s imperial legacy.

As one of Rome's most visited tourist attractions, the Arch of Constantine is a vital part of Italy’s cultural heritage. Its historical significance and its role in the visual landscape of the Roman Forum make it an irreplaceable artifact of human history. The damage caused by the recent lightning strike highlights the vulnerability of such ancient structures, especially in the context of modern climate change.

Lightning Strikes on Historical Monuments

Although not related to natural disasters or climate-related causes, we must mention an example that starkly demonstrates the importance of safeguarding historical monuments, which is none other than the destruction of the Parthenon during the siege of Athens in 1687.

At that time, the Turks had used the Parthenon to store gunpowder, which made it a target for the Venetian fleet. The Venetians, aware of the building's use as an ammunition depot, fired upon it—an act that might have been avoided under different circumstances but was seen as necessary in the heat of battle, even though it remains deeply regrettable. Before this incident, the Parthenon, which had been constructed two millennia earlier by the architects Ictinus and Callicrates during the Age of Pericles, was remarkably well-preserved.

Thus, just like the ravages of war, natural forces have also led to the destruction of significant structures. Some notable examples are the following stories, which prove that the higher the occurrence of severe thunderstorms in historical cities due to climate change, the larger the possibility to suffer historical tragedies, and loss of monuments.

- Lightning used to wreak havoc on Roman structures throughout the centuries, such as when it struck the Baths of Nero in AD 60, completely destroying them the following year.

- In Constantinople, similar incidents occurred, including the destruction of two columns by lightning in AD 548 and 1101.

- A comparable fate befell the column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome during the 14th century, with lightning severely damaging its top. Trajan's statue, atop his famous column, was also destroyed by a lightning strike during the same period.

- After the Roman Empire, the bronze statue of the Archangel Michael atop the Castel Sant'Angelo was also wrecked by lightning in 1572.

- In Rome, St. Peter's Basilica itself was struck 22 times between 1606 and 1809. Fortunately, after the final strike, Pope Pius VII had lightning rods installed, which have since effectively protected the church from further damage.

- Italian towers have met similar fates at the hands of lightning. In 1521, the tower of the Castello in Milan was destroyed, followed by the tower at Ivrea in 1676, San Nazaro’s tower in Brescia in 1769, and the fortress tower on the Lido near Venice in 1808.

- The 1914 lightning strike at Santamaria di Capua Vetere in Italy, where a 95-foot-high column of travertine marble, topped with a bronze statue of Victory, was severely damaged. The lightning shattered the statue and destroyed the top half of the column. Experts suggested that if a conductor had been installed to channel the electrical discharge into the ground, the structure might have been saved, as the insulating marble only exacerbated the damage.

The installation of lightning rods has since proven essential in protecting buildings from such strikes, just as international agreements may one day shield cultural heritage from the destructive force of human conflict.

As we look climate change in the eye, some dangers must be considered and lessons learned from past devastations must prompt us to protect historical and artistic treasures, ensuring they endure through future generations. (Immunity of Monuments, Museums, Libraries, Architectural and Historical Structures in War and Peace, by George Frederick Kunz)

Climate-Related Disasters and Their Impact on Historical Monuments

Cultural heritage sites, including archaeological monuments and historical structures, are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, fires, tsunamis, landslides, and storms. These disasters have devastating impacts, leading to the loss of irreplaceable cultural and artistic assets, especially in low-income countries, where infrastructure is often inadequate and risk preparedness is lacking.

In fact, natural disasters have been responsible for the destruction of some of the world’s most cherished cultural sites. One of the most famous examples of this destruction is the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which obliterated the cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and other nearby settlements, burying them under layers of volcanic ash. Such catastrophic events not only wipe out entire cultural landmarks but also erase centuries of history and civilization in a matter of moments.

In addition to large-scale catastrophic events, smaller but more frequent disasters such as floods and wildfires are becoming more prevalent due to climate change.

Venice Flooded during Thanksgiving 2010. Credits: A.Currell, CC BY-NC 2.0

In Barclay G. Jones book, “Protecting Historic Architecture and Museum Collections from Natural Disasters,” and in June Taboroff‘s article, “Cultural Heritage and Natural Disasters: Incentives for Risk Management and Mitigation,” we learn some significant details around the climate-related disasters that occur nowadays, even more often.

These events continue to threaten cultural heritage across the globe. While many nations have made efforts to safeguard their historical monuments, evidence suggests that awareness of the need to reduce these risks, remains low.

For instance, officials in Venice, a city known for its rich cultural history and iconic canals, have been slow to take substantial action against the increasing threat of flooding, despite scientific projections showing that such disasters are likely to quadruple in frequency over the next century due to rising sea levels and changing weather patterns.

According to the latest research, Venice, which once faced a flood only once every 800 years, is now at risk of facing such devastating floods every 20 years, driven by the combination of sea-level rise, land subsidence, and more intense storms.

Flooding

Flooding is one of the most common and destructive climate-related hazards affecting cultural heritage sites. Floodwaters can weaken the structural integrity of monuments, leading to collapse, erosion, and long-term water damage. Historic districts, such as those in coastal cities, are particularly vulnerable.

Floods can also cause damage to building contents, including priceless artifacts, and create residual moisture issues that lead to further decay over time. River flooding, such as the 1997 floods in East Germany, can quickly rise and cause immediate destruction, washing away portions of the buildings themselves or making foundations unstable.

The indirect damage caused by flooding is equally concerning. Erosion of the soil around buildings can undermine the structural foundation, collapse walls, and erode centuries-old stonework. Additionally, after floodwaters recede, residual moisture often lingers, promoting the growth of mold and mildew, which further damages both the structure and the artifacts inside. Additionally, buildings with basements are at risk of inundation of water and contamination of sewerage systems, further deteriorating their condition.

Florence and the 1966 Arno River Flood

One of the most famous instances of flood damage to cultural heritage is the 1966 flood of the Arno River in Florence, Italy. The floodwaters severely damaged museums, monuments, and artworks, including Roman structures and archaeological treasures.

The floodwaters reached up to 6 meters in certain areas, submerging churches, historical buildings, and even the renowned Uffizi Gallery. Many ancient Roman relics and manuscripts were lost to the waters, and the clean-up and restoration process took decades.

The Basilica di Santa Croce, where Michelangelo is buried, was submerged in floodwaters, and its ancient frescoes suffered severe damage from the water and silt deposits. This flood illustrated the extreme vulnerability of ancient structures to unexpected natural disasters.

Venice, though further north, was similarly affected by flooding during this period. With the city already sitting at sea level, the increasing frequency of high tides (acqua alta) combined with flooding makes Venice one of the most endangered cultural sites in Europe.

The Impact on Pompeii

While Pompeii is most famously known for its destruction by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, flooding remains a significant modern threat. Heavy rainfall has caused severe damage to parts of the Pompeii ruins, leading to collapses of ancient walls and the deterioration of frescoes and mosaics.

The city, a testament to Roman architecture and daily life, suffers from water infiltration as rain floods parts of the excavated city, eroding the foundations of many of the remaining structures. These instances illustrate that flooding doesn’t only damage the structural integrity of monuments but also contributes to long-term degradation of fragile historical sites.

Another example, is the historic site Of Petra in Jordan that faces frequent flash floods, which not only cause structural damage but also deposit large amounts of debris that further alter the landscape. Such damage is difficult to reverse and often requires extensive restoration efforts.

Wildfires

Fires are another significant hazard for cultural heritage sites. Fires can directly destroy ancient buildings, their contents, and historical landscapes. The damage caused by fire includes the destruction of objects by burning, heat, smoke, and firefighting efforts that can leave buildings vulnerable to collapse due to water saturation.

The risk of fire is particularly high in areas prone to dry, hot weather, often exacerbated by prolonged droughts. In regions like California, where wildfires are frequent, many historic properties have been lost in recent years.

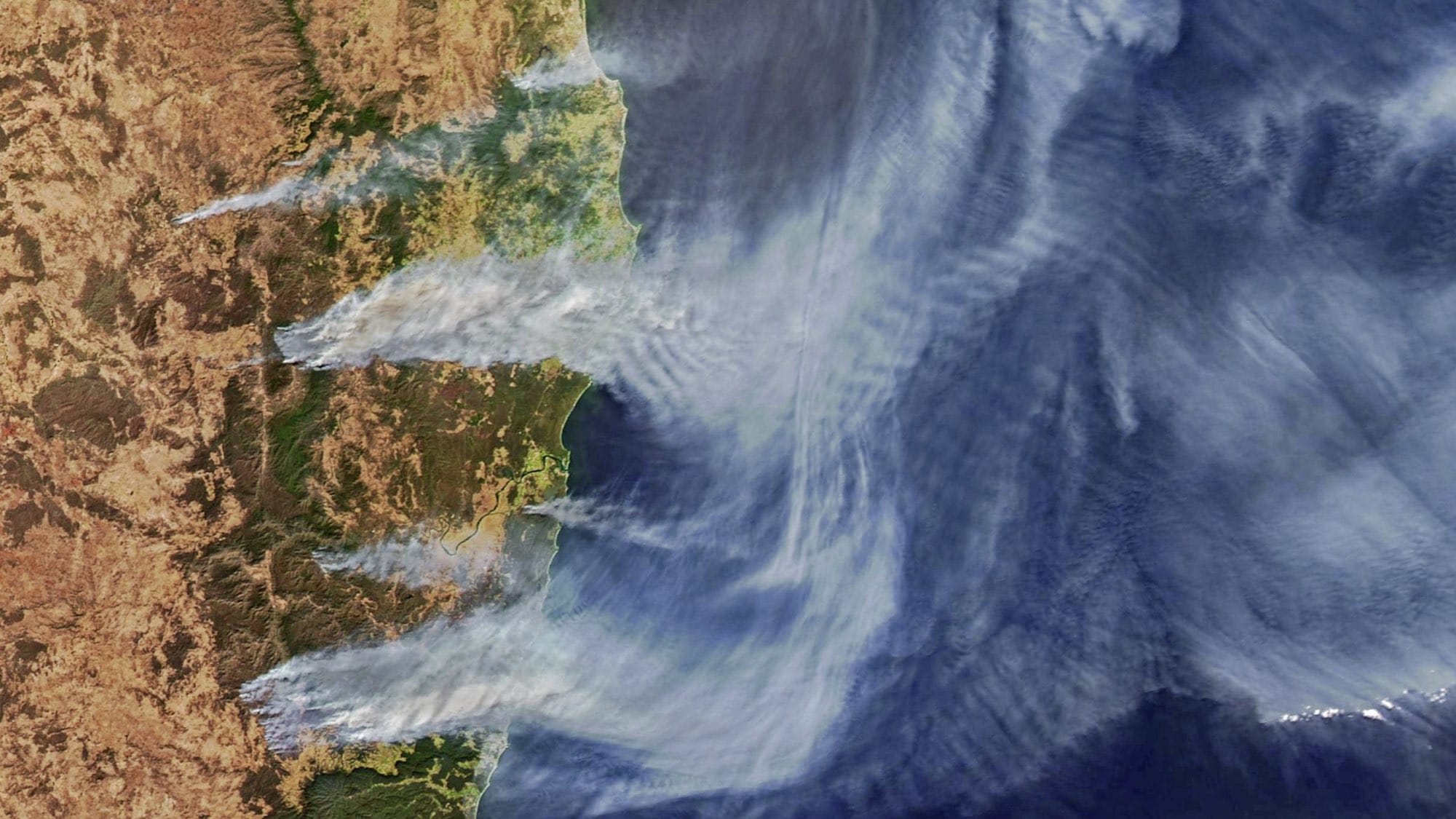

Fires can also destroy the natural surroundings of cultural heritage sites, as was the case during the devastating wildfires in Australia, which threatened several World Heritage-listed areas, including those rich with ancient Indigenous rock art.

Sea-level Rise

In coastal areas, increases in sea-level and storm surges threaten monuments located near shorelines. Rising sea levels, driven by climate change, are gradually submerging historical coastal towns and archaeological sites that have stood for millennia and are increasingly vulnerable as the natural landscape around them changes. Over time, rising seas can erode foundations and wash away structures, often irreversibly.

Storm surges on the other hand is a rising phenomenon in the Mediterranean basin—abnormally high waves and tides generated by powerful storms—can inundate entire regions, sweeping away buildings, roads, and bridges. Historical monuments, especially those located near bodies of water, are particularly vulnerable.

The Submersion of Baiae

Baiae, a luxurious Roman resort town near Naples, is a stark example of the threat of coastal change. Once a thriving hub of Roman wealth and leisure, much of the ancient town now lies submerged beneath the waters of the Gulf of Naples. A combination of volcanic activity and rising sea levels over centuries caused the city to sink, and today, much of Baiae is an underwater archaeological site.

While the submersion of Baiae began long ago, it illustrates the ongoing threat that rising seas pose to Roman coastal structures. If current trends continue, other coastal Roman sites, including those along the Mediterranean, could face similar fates.

Venice and Sea Level Rise

The city of Venice, although not Roman, presents a modern parallel to ancient coastal cities. Increasing sea levels and more frequent storm surges threaten Venice’s canals and historic architecture.

With each acqua alta, the saltwater erodes the foundations of Venice’s historic buildings, and more extreme flooding events could lead to catastrophic losses in the future. Given the cultural importance of Venice’s Roman and later architectural treasures, the preservation of the city against rising sea levels has become an international priority.

Damage to Roman Coastal Structures

In addition to rising seas, Roman structures along the coasts of Italy, Spain, and North Africa are vulnerable to storm surges. The ruins of Ostia Antica, the ancient port of Rome, have been affected by flooding and erosion as water from the Tiber River has increased due to changing weather patterns and storm surges.

Ostia, once a bustling Roman city, now faces the dual threat of flooding and subsidence. This is especially dangerous for the remaining mosaics, frescoes, and sculptures that provide valuable insight into Roman urban life.

Roman Coastal Sites in North Africa and Spain

Many Roman coastal settlements in North Africa, such as those in modern-day Tunisia and Libya, face the threat of rising seas. Cities like Leptis Magna, which boast some of the most well-preserved Roman ruins, are vulnerable to coastal erosion and flooding.

Similarly, Roman ruins along Spain’s coast are increasingly at risk as the Mediterranean rises, with ancient ports like Tarragona and its Roman remains facing damage from saltwater intrusion and erosion.

The Turkish coast is another example; it is home to several ancient sites now located underwater due to centuries of coastal changes and rising seas. Without adequate infrastructure, many coastal monuments face the threat of gradual submersion or severe erosion.

This phenomenon is not limited to the Mediterranean Sea; across the globe, coastal cities like parts of Southeast Asia are also seeing heritage sites at risk of being washed away by rising tides. Furthermore, changes in river courses over time have altered the landscape surrounding many historical monuments, making them more vulnerable to flooding or isolation from their original contexts.

Violent Storms

Tropical-level storms and high winds are also common threats to cultural heritage, particularly in tropical regions.

Such storms can tear apart buildings, remove roofing materials, and displace stones or architectural elements, leaving historic structures vulnerable to further degradation. High winds can dislodge essential building materials from monuments, eroding their structural integrity and accelerating their decay.

Windstorms, particularly those reaching hurricane force, have the potential to destroy roofs, knock down walls, and uproot trees that may collapse onto nearby structures.

Hurricane Camille and U.S. Monuments

Although not Roman, Hurricane Camille in 1969 serves as an illustrative example of how high-wind storms can devastate heritage sites. In this case, historical structures in the path of the hurricane suffered significant damage.

Entire roofs were torn from buildings, and floodwaters caused additional damage. Mobile, Alabama’s historic districts, home to buildings dating back to the 19th century, were particularly hard hit. Camille’s devastation exemplifies the power of high winds and the immediate, catastrophic damage they can inflict on monuments and historical structures.

Storms Impacting Roman Sites

Roman monuments in areas that experience regular storms are also at significant risk. The columns of the Roman Forum in Rome have experienced wear and erosion from heavy rainstorms over the centuries. High winds have caused damage to some of the remaining structures, especially those that are already fragile due to age.

Lightning strikes during storms have also historically damaged Roman structures. As aforementioned, the Column of Trajan, one of Rome’s most famous monuments, was damaged by a lightning strike in the 14th century, causing the destruction of the statue of Trajan that once stood atop the column.

The statue was later replaced with a figure of St. Peter, but the structural damage caused by that storm remains a reminder of how nature can alter history.

Landslides

Landslides and mudslides, which often occur in hilly or mountainous regions, pose additional risks. These hazards are frequently triggered by other disasters, such as heavy rainfall or earthquakes.

In mountainous areas of Europe, including the Italian Alps, landslides and avalanches are not uncommon and have been responsible for destroying properties and historical landmarks. Landslides deposit debris and mud over archaeological sites, potentially burying them permanently or causing significant damage that is difficult and expensive to repair.

Tsunamis

These massive tidal waves typically caused by underwater earthquakes, but further strengthened by the rising sea levels—pose an immediate and catastrophic risk to coastal heritage sites. These tidal waves can inundate entire regions, washing away buildings, monuments, and landscapes, much like high-force flooding.

The Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 provides a sobering example of how tsunamis can lead to significant loss of life and cultural heritage. While the damage from tsunamis is rare, when they do occur, they are often disastrous, especially for low-lying coastal heritage sites in regions like Southeast Asia and the Pacific Basin.

Are Our Monuments Prepared for Climate Disasters?

With climate change accelerating the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, monuments like the Arch of Constantine face increasing risks. Lightning, while rare, can be devastating when it strikes an unprotected stone structure, especially one that is nearly 2,000 years old.

In addition to storms, other climate-related threats, such as rising sea levels, flooding, drought-induced wildfires, and temperature fluctuations, are becoming more prevalent. The question of how to protect these invaluable cultural assets is becoming more urgent.

Many heritage sites around the world have already faced destruction or damage due to climate disasters. According to a report by the Global Citizen, climate change is a direct threat to the preservation of heritage sites globally, with rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and increased natural disasters causing irrevocable damage.

Protecting ancient monuments from such disasters requires a multi-faceted approach that includes both preventative measures and rapid response strategies.

- Climate-Resilient Infrastructure: One of the most effective ways to protect historical monuments is through the installation of modern protective systems. For example, extra lightning rods and grounding systems can be added to monuments like the Arch of Constantine to prevent future lightning strikes from causing damage. In areas prone to flooding, protective barriers and drainage systems can be installed to minimize the impact of rising water levels.

- Continuous Monitoring and Maintenance: Regular monitoring of historical structures is essential for detecting vulnerabilities before they lead to catastrophic damage. Advanced technologies, such as 3D scanning and drones, allow preservationists to monitor the structural integrity of monuments in real time, identifying cracks, erosion, or other signs of wear that could be exacerbated by a natural disaster.

- International Cooperation: The preservation of historical sites is a global responsibility. International organizations, such as UNESCO, play a critical role in coordinating efforts to protect monuments from climate disasters. Initiatives such as the World Heritage Convention encourage countries to invest in safeguarding their cultural heritage while providing access to resources and expertise to address specific risks related to climate change.

- Public Awareness and Involvement: Raising awareness of the dangers posed by climate change to historical monuments is crucial for garnering public and governmental support for preservation efforts. The involvement of local communities in the protection of their cultural heritage is an essential component of ensuring long-term sustainability.

As emphasized in the research “Proceedings of the Geological and Geotechnical Influences in the Preservation of Historical and Cultural Heritage,” by George Pararas-Carayannis, preserving monuments against natural disasters requires both technological advancements and a collective societal effort to mitigate risks.

Countries with rich cultural histories like Italy must prioritize the protection of their historical monuments, not just for the sake of preserving national identity, but also for the benefit of future generations.

The Broader Context of Monuments and Climate Change

The damage to the Arch of Constantine is not an isolated incident. Across the globe, climate change is threatening some of the world’s most cherished heritage sites.

According to UNESCO, over a quarter of World Heritage Sites are at risk due to climate change.

The submerged mosaics of Baia, Italy. Credits: Parco archeologico sommerso di Baia

While modern cities can often rebuild after a disaster, ancient monuments cannot be replaced. Once damaged or destroyed, the historical and cultural value of these structures is diminished forever. As climate change accelerates, the world must reckon with the reality that many of its most important historical sites may not survive without immediate and sustained intervention.

The lightning strike on the Arch of Constantine serves as a wake-up call for governments, preservationists, and the general public. As climate disasters become more frequent and severe, the need to protect our cultural heritage has never been more pressing. While the damage to the arch is reparable, the event highlights the fragility of ancient structures in the face of modern environmental challenges.

Preserving the legacy of the Roman Empire, and all other ancient civilizations, for future generations will require a concerted effort that includes both modern technology and traditional conservation techniques. The Arch of Constantine may have survived for nearly two millennia, but if we are to ensure that it stands for another thousand years, we must act now.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: