Caesarion: Was the Last Pharaoh, the Son of Julius Caesar?

Caesarion was born in 47 BCE, and his mother Cleopatra claimed that he was Julius Caesar's son.

Caesarion, formally known as Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar, was the last Pharaoh of Egypt and the son of Cleopatra VII. His nickname "Caesarion" means "little Caesar," reflecting his connection to Julius Caesar.

Caesarion is a figure about whom we know very little. His actions, appearance, and personality are not recorded in detail, leaving us with little direct information about him. He was killed at the age of seventeen, an event that is only briefly mentioned in historical accounts. However, his significance can be inferred from the fact that he is mentioned at all.

Though he may not have truly ruled, Caesarion was a king in name, and his birth and death were part of grand political designs.

Relief depicting Cleopatra (left) and Caesarion (right) as King. Credits: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0

Cleopatra, the Mother

From the moment of his birth, Caesarion was part of the ambitions and plans of powerful figures around him, shaped by the political circumstances of the time. As already mentioned above, as the possible son of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar, he was given the nickname Caesarion, or "Little Caesar," by the Alexandrians when he was still a child. Officially, he was called Ptolemy Caesar, often listed as Ptolemy XV.

Despite being referred to as a king, he also held the title of Pharaoh, reflecting the dual identity of Egypt under the Ptolemies, with their Hellenistic kingdom centered in Alexandria and their traditional role as rulers of the larger native Egyptian realm. The later Ptolemies, including Caesarion, were crowned at Memphis by the high priest of Ptah, maintaining their connection to native Egyptian traditions while ruling from their Greek-influenced capital.

Caesarion's birth was the result of two intersecting civil wars—one in Egypt and the other in Rome. The Egyptian civil war arose from the legacy of his grandfather, Ptolemy XII, who was called "the Flute Player" (Auletes) by his subjects. Auletes had been ousted from the throne due to his unpopular reign, which was marked by his dependence on Rome. He was restored to power by Roman forces in 55 BC, supported by both Pompey and Caesar.

However, the huge debts he incurred to secure this help were passed down to his successors, including Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIII. Ptolemy XII’s will dictated that Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII would rule jointly after his death, but this arrangement quickly fell apart. Cleopatra, unwilling to share power with her brother, was driven out of Alexandria by a court faction led by the eunuch Pothinus and his ally Achillas.

Meanwhile, in Rome, the civil war between Caesar and Pompey was intensifying. Pompey fled to Egypt after being defeated at the Battle of Pharsalus, expecting support from the boy-king Ptolemy XIII, whose father he had helped restore to the throne. However, Pompey was murdered upon his arrival in Egypt, with Ptolemy XIII watching the event unfold from the shore.

Caesar, the Father

Caesarion was an essential figure in the tumultuous political dynamics of the late Roman Republic. Despite being an essential pawn in the political chessboard of his era, there is very little recorded about Caesarion's own actions or personality. His birth was a result of the Egyptian and Roman civil wars, which thrust him into the center of shifting allegiances, grand ambitions, and imperial power struggles.

Caesarion's birth came at a time when Cleopatra hoped to cement an alliance with Julius Caesar and potentially place her son in a position of influence in Rome. The relationship between Cleopatra and Caesar was strategic, and she may have envisioned Caesarion playing a role not only as a future ruler of Egypt but also as a figure in Roman political life. His birth was a calculated move, meant to strengthen Cleopatra’s position and secure the future of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Throughout Caesarion’s life, he was constantly used as a political tool. His mother, Cleopatra, showcased him as Julius Caesar's legitimate heir, especially during her visit to Rome in 46 BC. Although Caesar never publicly disavowed him, he did not name Caesarion as his successor in his will. This led to future conflicts, especially after Caesar’s assassination when Cleopatra returned to Egypt with Caesarion, positioning him as her co-ruler.

After the downfall of Cleopatra and Mark Antony in 30 BC, Caesarion’s life quickly unraveled. Despite attempts by Cleopatra to protect him, Octavian (the future Augustus) saw him as a threat. Caesarion was captured and executed, marking the end of the Ptolemaic line and the beginning of Egypt's annexation into the Roman Empire.

Caesarion’s story exemplifies how royal offspring were often pawns in the larger political games of powerful rulers, his brief life marked by the ambitions of his parents and the shifting tides of Roman politics.

Antony, the Guardian

The triumvirs divided the Roman world after their victory at Philippi, with Antony taking control of the eastern provinces. Octavian and Lepidus governed the west, though Lepidus was gradually sidelined, leaving Octavian as the primary ruler in the west.

Despite this, Antony was still seen as the senior figure, particularly in the east. Cleopatra, seeking to secure her position and her son Caesarion's future, aligned herself with Antony.

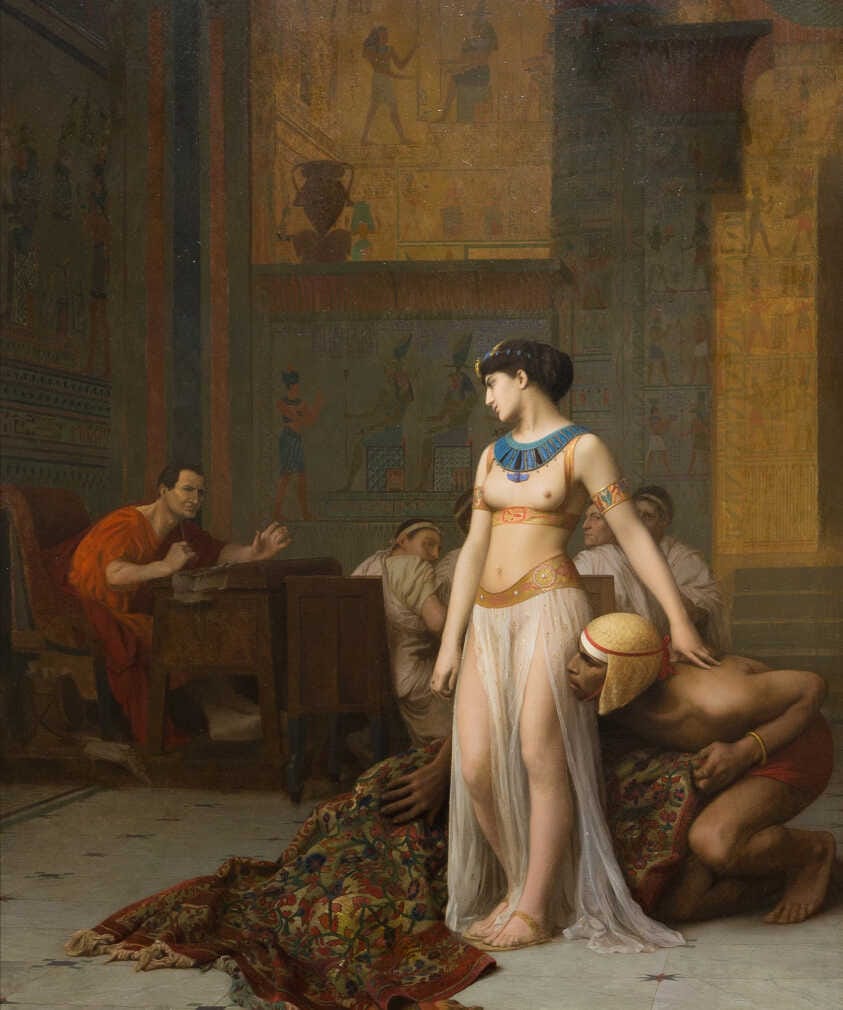

Their legendary meeting at Tarsus marked the beginning of their political and personal alliance.

Charles Joseph Natoire, The Interview of Cleopatra and Mark Antony at Tarsus. Credits: jean louis mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Cleopatra's relationships with Julius Caesar and Antony were primarily driven by political motives. Despite later propaganda portraying her as a promiscuous seductress, she only had significant relationships with these two men. Her primary goal was to secure her reign in Egypt and the future of Caesarion, her son with Caesar, and her children with Antony.

Antony, although married to Octavian's sister Octavia, rekindled his relationship with Cleopatra in 37 BC, producing more children. Caesarion's position remained important, though potentially vulnerable as Cleopatra had more children with Antony. Antony’s political maneuvers, particularly the "Donations of Alexandria," where he granted Cleopatra vast territories and proclaimed Caesarion "King of Kings," worried many in Rome and intensified Octavian's campaign against him.

Antony’s formal declaration that Caesarion was the son of Julius Caesar further complicated matters, especially with Octavian, who viewed this as a threat to his own position as Caesar’s heir. This proclamation heightened tensions between Antony and Octavian and played a crucial role in the propaganda that would eventually lead to Antony’s downfall and the deaths of Cleopatra and Caesarion.

Octavian, the Murderer

As tensions grew between Octavian and Antony, the two surviving triumvirs of Rome, a prelude to open conflict emerged through a war of words and propaganda. Octavian commissioned Gaius Oppius, a former confidant of Julius Caesar, to write a pamphlet denying Caesarion's paternity, asserting that Caesar was not his father.

Antony, however, had previously cited Oppius as one of the witnesses who had heard Caesar acknowledge Caesarion as his son in private conversations. Octavian’s attempt to challenge Caesarion’s legitimacy through this pamphlet reflects his growing concern about the young boy’s potential claim to power.

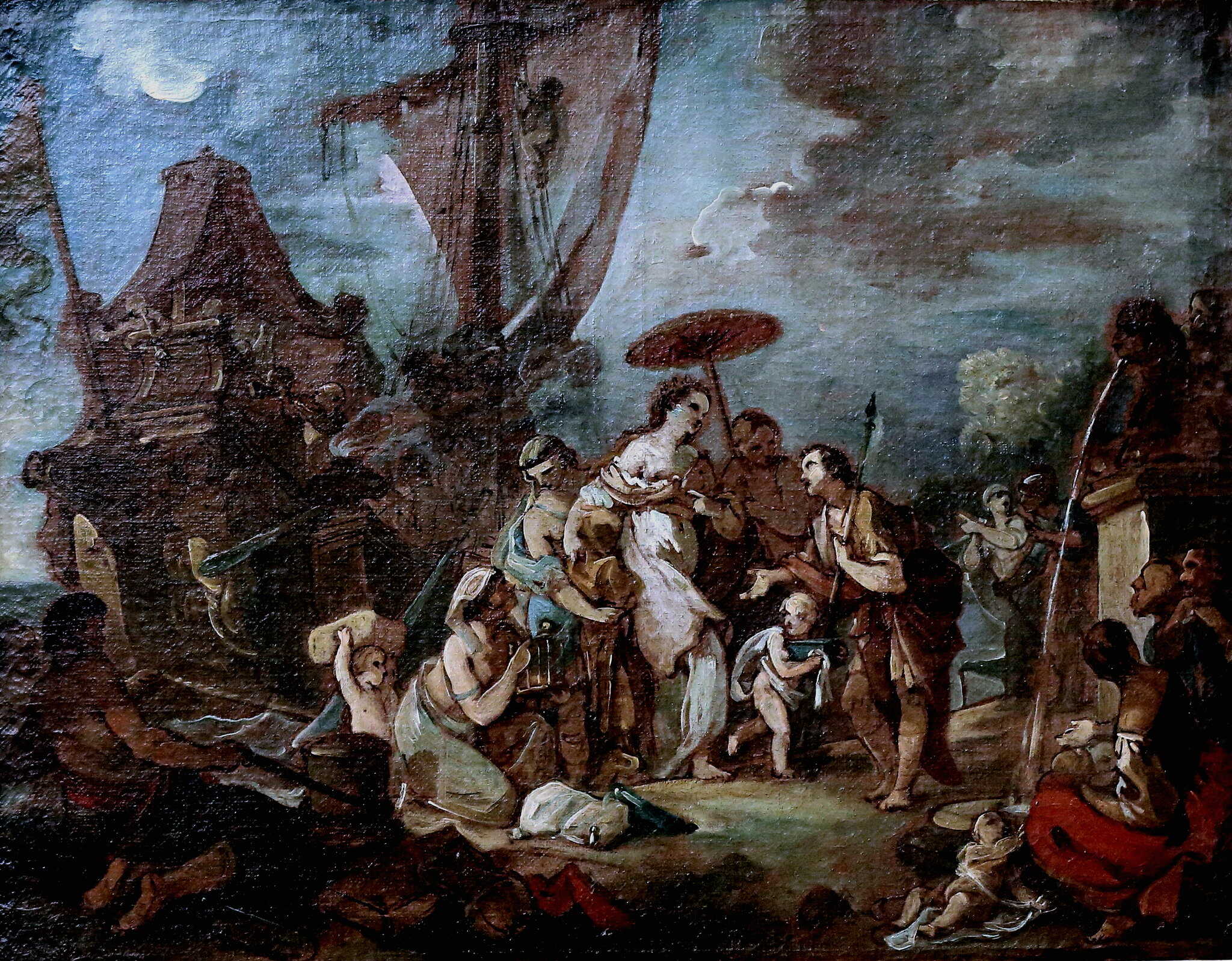

The propaganda war was mainly directed against Cleopatra, portraying her as a manipulative figure who had Antony under her control.

Even Cleopatra’s depictions in modern art reflect the same propaganda elements. Painting by Jar Steen, The feast of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Public domain

Octavian's strategy aimed to win over those undecided between him and Antony by framing the conflict as one between Rome and an ambitious Egyptian queen seeking to rule the Roman Empire from Alexandria. Meanwhile, in Alexandria, Caesarion, who was about sixteen at the time, was receiving an education alongside Antony’s son, M. Antonius Antyllus. Cleopatra ensured that Caesarion, while being prepared for his role as Egypt’s ruler, learned both Latin and Greek, maintaining the possibility of a future in both Egypt and Rome.

As the inevitable war approached, Antony and Cleopatra gathered their forces, and by 32 BC, Caesarion and Antyllus underwent rites of passage into adulthood. Caesarion was formally enrolled as an ephebe, marking him as ready for military training, while Antyllus assumed the toga virilis, a Roman symbol of manhood.

After their defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, Cleopatra began making plans to save her son, including a failed attempt to send Caesarion to safety in India. Despite her efforts, Octavian eventually captured Caesarion, and he was executed—though details of his death remain unclear. (What to do with Caesarion, by Michael Gray-Fow)

Caesar’s Numerous Affairs, and Possible Children

Rumors and suspicions surrounding Julius Caesar’s relationships with foreign queens, like his alleged affair with Eunoe, the wife of King Bogud of Mauretania, share similarities with the accusations involving Nicomedes of Bithynia. These rumors often relied on tenuous evidence, such as Caesar’s lavish gifts to Bogud and Eunoe, which were more likely political gestures in gratitude for military support than romantic entanglements.

These suspicions were fueled by anti-Caesarian figures like M. Actorius Naso, known for spreading negative stories about Caesar. The most famous of these alleged affairs, of course, was with Cleopatra VII. Caesar’s extended stay in Egypt for nine months after backing Cleopatra’s claim to the throne was seen as suspicious by many in Rome.

However, this lengthy stay can be attributed to the complex political situation in Egypt, rather than purely romantic motivations. Back in Rome, his critics, like Cicero, were eager to know when Caesar would return, and Cleopatra’s later visit to Rome with her co-ruler Ptolemy XIV during Caesar’s triumphs further fueled gossip.

Cleopatra’s arrival in Rome sparked rumors, especially with her lavish gifts and the dedication of her gold statue in Caesar’s newly built Temple of Venus. While some interpreted this as the act of a smitten lover, it is more likely that the statue, along with other artistic works in the temple, was meant to celebrate Caesar’s achievements and connections with prominent rulers of the Hellenistic world.

The birth of Caesarion was seen by some as proof of their liaison, but sources like Plutarch suggest uncertainty regarding whether Caesar was alive when the child was born, implying that Caesarion may have been born after Caesar’s assassination. While Caesar’s contemporaries like Antony acknowledged Caesarion as Caesar’s son, others, including G. Oppius whom —as aforementioned— Antony used as a source for the rumours, disputed this claim in their official statements.

The lack of definitive evidence and the political manipulation of such rumors contributed to an atmosphere of constant gossip regarding Caesar’s relationships. These suspicions extended even to elite Roman women, including the wives of prominent figures like Pompey and Crassus, although the evidence for these affairs is similarly fragile and politically motivated.

Overall, many of these accusations relied on the assumption that there is "no smoke without fire," but the actual evidence is often embedded within political rhetoric and may not be entirely reliable. The historian must, therefore, approach such stories with caution, recognizing the political motivations behind their propagation. (“Caesar the man” by Jeremy Paterson, in “A companion to Julius Caesar, edited by Miriam Griffin)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: