Brothers Divided: The Tragic Tale of Emperors Caracalla and Geta

As the Severan dynasty rose to prominence, the two brothers were groomed to jointly inherit their father’s empire. Despite their shared upbringing, their differences—both personal and political—were stark and irreconcilable.

In the shadowed halls of Rome’s imperial palace, two brothers stood poised on the precipice of destiny. Caracalla and Geta, heirs to the mighty Severan dynasty, seemed destined to rule together in harmony. Yet behind the veneer of shared power simmered a rivalry so bitter it would tear apart not only their family but the empire itself.

As whispers of betrayal echoed through the marble corridors, blood would be spilled, and history would forever remember their names—not for unity, but for treachery and fratricide. What truly transpired between the sons of Septimius Severus, and how did their enmity shape the Roman Empire?

Caracalla (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, later Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, was nicknamed Caracalla after the name of a long-hooded tunic of Gallia which he was fond of wearing) and Publius Septimius Geta were the sons of Emperor Septimius Severus and Julia Domna, a powerful empress of Syrian descent. As the Severan dynasty rose to prominence, the two brothers were groomed to jointly inherit their father’s empire.

Despite their shared upbringing, their differences—both personal and political—were stark and irreconcilable.

“As brothers they were also mutually antagonistic; this dated back to their rivalry as children when they quarrelled over quail fijights or meetings in the cock-pit or wrestling bouts with each other.

Their divided interests in the theatre and recitations also always encouraged this rivalry because they never had the same tastes; anything one liked, the other hated.”

Herodian

The Story of Caracalla and Geta: Sibling Rivalry Turned Tragedy

In 198 CE, at the tender age of 10, Caracalla was elevated to the rank of Augustus, marking him as a co-emperor alongside his father. Geta, younger by a year, was given the title of Caesar—a junior rank in the imperial hierarchy. This disparity sowed the seeds of resentment, as Geta was relegated to a lesser role despite being equally ambitious.

In 209 CE, Geta was finally granted the title of Augustus, but by then, the rivalry between the brothers had solidified. He was well-liked by many because of his amiable nature, balanced temperament, and gentle demeanor. In contrast to his brother, he treated others with kindness and respect, earning him widespread friendship and goodwill.

Their father, sought to mitigate their discord, even orchestrating campaigns to unite them through shared military glory. His final advice to his sons, on his deathbed in 211 CE at Eboracum (modern-day York), was succinct yet futile: “Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all others.” This counsel would go unheeded.

After Severus’ death, the brothers inherited an empire that stretched from Britannia to the edges of the Parthian kingdom. Yet their reign was marred by constant disputes. They divided the imperial palace, each claiming separate quarters and avoiding one another entirely.

Their governance mirrored this division, with each brother appealing to different factions within the empire. Caracalla favored the military, cultivating loyalty among the legions, while Geta leaned on the support of the Senate and urban elites.

Image #1: Public domain

Image #2: Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5

“His [Severus’] sons, who were by now young men, hurried back to Rome with their mother, but already on the return journey there were serious differences between them.

For example, they did not stay at the same lodging houses nor take a meal together.

Each was extremely circumspect with everything he ate and drank in case the other quietly made the first move, or persuaded some of the attendants to administer a fatal dose of poison.

Hence there was even greater haste on the journey, since they both believed they would breathe more safely when they reached Rome and divided up the palace, where they could each live their separate lives according to their own interests in a vast, spacious building that was bigger than any city.”

Herodian

The tension escalated to the point where plans were made to formally divide the empire, with Caracalla ruling the western provinces and Geta the eastern territories. However, this arrangement was never finalized, as such a division would undermine the unity of the Roman state—a prospect the legions, particularly, were unwilling to accept.

In December 211 CE, the rivalry reached its bloody climax. Historical accounts, particularly from Cassius Dio and Herodian, describe how Caracalla lured Geta to a meeting under the guise of reconciliation. In the safety of their mother Julia Domna’s arms, Geta was ambushed by Caracalla’s guards and brutally murdered.

Contemporary sources recount that Geta bled to death in his mother’s embrace, a harrowing end to their tragic sibling saga.

A painting by Léon Cogniet, of Caracalla trying to murder his brother Geta in front of their mother. Credits: jean louis mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

"Antoninus wished to murder his brother at the Saturnalia, but was unable to do so; for his evil purpose had already become too manifest to remain concealed, and so there now ensued many sharp encounters between the two, each of whom felt that the other was plotting against him, and many defensive measures were taken on both sides.

Since many soldiers and athletes, therefore, were guarding Geta, both abroad and at home, day and night alike, Antoninus induced his mother to summon them both, unattended, to her apartment, with a view to reconciling them.

Thus Geta was persuaded, and went in with him; but when they were inside, some centurions, previously instructed by Antoninus, rushed in in a body and struck down Geta, who at sight of them had run to his mother, hung about her neck and clung to her bosom and breasts, lamenting and crying: "Mother that didst bear me, mother that didst bear me, help! I am being murdered."

And so she, tricked in this way, saw her son perishing in the most impious fashion in her arms, and received him at his death into the very womb, as it were, whence he had been born; for she was all covered with his blood, so that she took no note of the wound she had received on her hand.

But she was not permitted to mourn or weep for her son, though he had met so miserable an end before his time (he was only twenty-two years and nine months old), but, on the contrary, she was compelled to rejoice and laugh as though at some great good fortune; so closely were all her words, gestures, and changes of colour observed.

Thus she alone, the Augusta, wife of the emperor and mother of the emperors, was not permitted to shed tears even in private over so great a sorrow."

Cassius Dio

The Legacy of Caracalla: Power, Perception, and the Shadow of Fratricide

Following this act of fratricide, Caracalla became the sole emperor, burdened with the challenge of legitimizing his rule and distancing himself from the stigma of being a brother-killer. Today, he is often regarded as a quintessential soldier emperor. Many modern historians assume that his efforts to consolidate his power relied predominantly on military achievements.

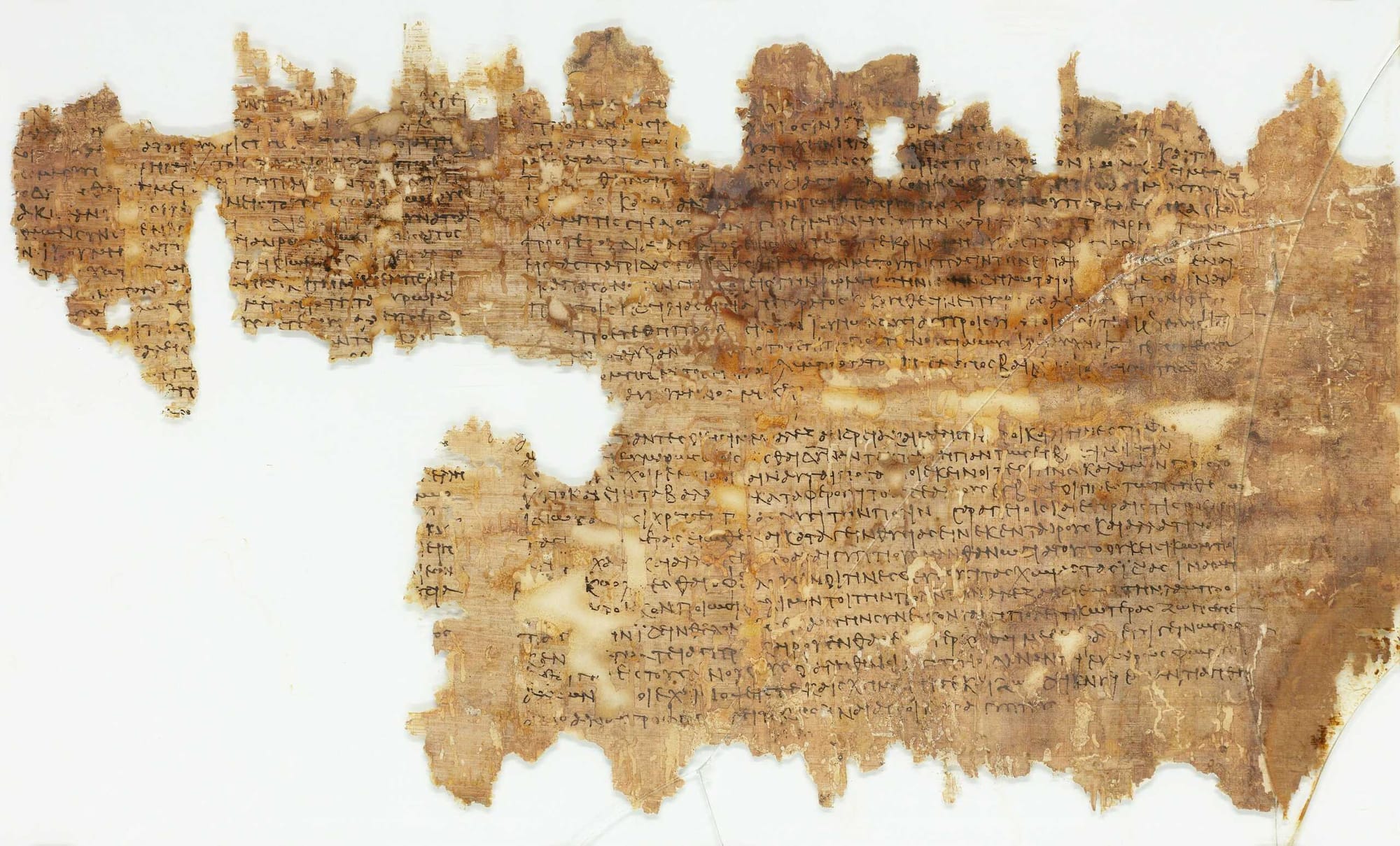

His efforts to shape his image can be discerned through various sources. Coins, for example, depicted his portraits alongside themes of power on their reverses, while inscriptions and papyri reflected his titles and salutations. Architectural projects and their locations offered further insight into his priorities.

Contemporary historiographical accounts, although influenced by elite biases and often subjective, provide valuable supplementary context to these material sources. Caracalla’s path to legitimacy highlights the complex interplay of power, perception, and public image in the Roman imperial system, shaped by both necessity and strategic calculation. (The Impact of Imperial Rome on Religions, Ritual and Religious Life in the Roman Empire, by Lukas de Blois, Peter Funke, Johannes Hahn)

Caracalla and the Antonine Constitution: Rebuilding Legitimacy After Fratricide

The transition from the joint rule of Severus' sons in early AD 211 to Caracalla's sole rule by the end of the same year was marked by unprecedented violence within the imperial household. Ancient sources such as Dio and Herodian, while differing in certain details, agree on the brutality of the final conflict: Geta as already mentioned, was fatally stabbed while seeking refuge with their mother.

Although their rivalry was widely known, his assassination was a significant turning point in Roman history. While emperors had been murdered before, this marked the first time that an emperor was killed by a co-ruler who already shared power. His dramatic and public elimination of his brother left him vulnerable, raising questions about the legitimacy of his reign.

The nearly constant portrayal of him and Geta by their father, as symbols of imperial harmony further compounded this vulnerability.

A cameo depicting Emperor Septimius Severus and his wife Julia Domna on the left, and the brothers Caracalla and Geta on the right. Photo courtesy of BNF

By early AD 212, his position as the sole ruler of the empire appeared precarious. In response, he was compelled to address recent events publicly, including the murder of his brother. The Constitutio Antoniniana (Antonine Constitution) became a central tool in this process.

This edict extended Roman citizenship to virtually all free inhabitants of the empire. While scholars like Mennen and Honoré have examined its broader social implications, its political utility for Caracalla in the fraught aftermath of Geta’s death deserves closer analysis.

The Constitutio Antoniniana served to consolidate his regime through three interconnected strategies:

- Religious Ideology: The text of the edict emphasized his personal piety and allowed him to shape the narrative surrounding Geta’s assassination. By presenting himself as divinely favored, Caracalla sought to mitigate the public perception of his violent actions.

- Imperial Generosity: The promotion of indulgentia (imperial generosity) was a traditional virtue of Roman emperors, but it took on unique significance in his case. The edict allowed him to project an image of magnanimity, reinforcing his authority and aligning himself with the interests of the broader populace during a time of instability.

- Patron-Client Relationship: Viewed through the lens of Roman patronage, the edict functioned as a social contract between him and the newly enfranchised citizens. By granting citizenship, he established a direct personal bond of loyalty with his subjects, reinforcing his claim to power and redefining the Severan dynasty’s character.

Caracalla’s Reinvention of Power

The year AD 212 began with unprecedented challenges for Caracalla, whose sole reign followed the brutal fratricide of his brother, marking a watershed in Roman history. Unlike his father who overcame political and military hurdles to secure power, he ascended to sole rule through an act of violence unparalleled in the imperial household.

Scholars have argued that the murder of Geta and the lack of an heir effectively doomed the Severan dynasty, compelling him to abandon its traditional familial propaganda and redefine his image as emperor. While he could no longer rely on his father's themes of dynastic unity, it is inaccurate to suggest that he rejected the Severan dynasty outright.

As Severus' eldest son, he had been a key figure in the dynasty since AD 198 and remained so even after his brother’s demise. Rather than renouncing his lineage, he sought to redefine it, transforming his narrative from one of familial harmony to a tale of divine intervention and triumph over evil, embodied in his conflict with his brother.

Central to this transformation was the damnatio memoriae of Geta, which Caracalla pursued with unparalleled intensity.

A detail of the tempera painting of Septimius Severus and his family, focusing on Caracalla as a child. Credits: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ancient sources like Dio report that he ordered his brother's statues destroyed, foundation stones defaced, and coins bearing his image melted down. While some coins and inscriptions have survived, the overwhelming erasure of Geta’s legacy underscores the effectiveness of this campaign.

Statues were destroyed or repurposed, and public records mentioning his brother were almost entirely obliterated. This thorough elimination of his brother's memory, whether motivated by hatred or a desire to symbolize his brother as an agent of evil, was instrumental in consolidating Caracalla’s rule.

In parallel with erasing Geta’s legacy, he crafted a new self-image, evident in his official portraiture. Early images of him were influenced by Antonine aesthetics, reflecting Severus’ efforts to associate the dynasty with earlier emperors.

However, after 212, his portraits adopted a stark militaristic style, marked by a cropped hairstyle and furrowed brow. Rather than signaling cruelty, this severe visage likely aimed to convey virtus—a quality revered by the Roman military—and possibly stoicism, reinforcing his popularity among soldiers and projecting strength as a ruler.

The Constitutio Antoniniana thus allowed him to simultaneously address multiple facets of his propaganda on a grand scale. By redefining his narrative, erasing his brother’s legacy, and forging a new bond with his subjects, Caracalla endeavored to consolidate his power and reimagine the Severan dynasty in the aftermath of fratricide. (The Antonine Constitution. An Edict for the Caracallan Empire, by Alex Imrie)

Public Works, Citizenship, and Economic Reforms

Caracalla’s historical legacy often receives little recognition for benevolence or accomplishments. However, three key contributions stand out: the construction of the Baths of Caracalla, plus the aforementioned issuance of the Constitutio Antoniniana, and reforms in Roman coinage.

The Baths of Caracalla (Thermae Antoninianae), completed in 216 AD, are often attributed to him, though the initial plans were likely drawn up by his father. The completion of this grand project appears to have been driven by political motives, serving as a means of propaganda to enhance his image and gain favor with the public.

The Constitutio Antoniniana, while it might appear egalitarian, was heavily influenced by his need to portray himself as a just and benevolent ruler. In practice, the edict created two distinct social classes:

- A privileged upper class with greater rights and protections

- A lower class subjected to harsher legal penalties and fewer privileges

Moreover, the increase in the citizen base allowed the Emperor to impose and collect more taxes, providing a much-needed boost to the empire's revenue—particularly critical given his generous monetary rewards to the military. His economic policies also had to include significant changes to Roman coinage.

To address financial deficits and fund increased army pay, he debased the silver content of coins by approximately 20%, reducing the purity from 58% to 50%. Additionally, he introduced a new coin, the antoninianus, which was nominally valued at two silver denarii but contained only 1.5 denarii worth of silver. This innovation further contributed to the debasement of Roman currency and strained the economy.

The Atrocities of Caracalla: A Reign of Violence and Vengeance

Caracalla’s reign is marred by a long list of atrocities, which historians recount with a palpable sense of dismay and abhorrence. It is of course expected that his most infamous act was the culmination of his lifelong animosity toward his younger brother, whom he ultimately assassinated. This act of fratricide set the tone for a rule characterized by relentless cruelty.

His treatment of his wife, Plautilla, was similarly ruthless. She was banished and later assassinated under his orders.

A Roman finger ring, featuring a double portrait of Emperor Caracalla and his wife Plautilla. Public domain

His cruelty extended even to his own father, Septimius Severus, during their British campaigns. Edward Gibbon, in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vividly describes this: “The declining health and last illness of Severus inflamed the wild ambition and black passion of Caracalla's soul. Impatient of any delay or division of empire, he attempted, more than once, to shorten the small remainder of his father's days and endeavoured, but without success, to excite a mutiny among the troops.”

Following Geta’s assassination, he unleashed a massacre targeting all those associated with his brother—friends, supporters, and even casual acquaintances. It is estimated that more than 20,000 people were executed, and a damnatio memoriae was imposed on Geta, as mentioned above. All depictions of his brother—statues, inscriptions, and coinage—were systematically destroyed. This purge extended beyond Rome to the provinces, where further executions were carried out under the same pretext.

After leaving Rome in 213 AD, Caracalla spread his brutality across the empire. In every province he visited, he imposed heavy fines and taxes, confiscated property, and carried out executions. One of his most infamous acts occurred in Egypt, where he ostensibly visited to honor Alexander the Great’s memory. In reality, he sought revenge against the Alexandrians for ridiculing him. Under his command, thousands were massacred in cold blood.

The Emperor's cruelty extended to his dealings with the Parthian Empire. Feigning a desire for peace, he proposed a marriage alliance with the Parthian king’s daughter. The Parthians, believing in his sincerity, came out in large numbers to welcome him. What followed was a horrific betrayal, as he commanded his army to massacre the unsuspecting Parthians. (Caracalla from innocence to villainy: as recorded by his coin engravers, by George Halabi)

These acts of treachery, vengeance, and bloodshed cement Caracalla’s legacy as one of Rome’s most violent and ruthless emperors.

A fragmented bronze portrait of the emperor Caracalla. Credits: MET, CC0 1.0

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: