Boudica: The Warrior Queen's Stand Against Rome's Conquest of Britannia

Boudica was a legendary warrior queen who led a major uprising against Roman rule in ancient Britannia. Discover her motivations, the impact of her rebellion, and how her legacy as a symbol of resistance has endured through history.

Boudica, the queen of the Iceni tribe, led a national rebellion that almost drove the Romans out of Britain.

The conquest of Britannia by Rome, which marked the beginning of the Roman influence in Britain, began in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius. The Roman military rapidly established control over the southern tribes of Britain following the initial landing commanded by Aulus Plautius.

Despite previous, less concerted efforts by Julius Caesar in 55 and 54 BC, it was Claudius' campaign that truly integrated Britain into the Roman Empire, with the construction of roads, towns, and military fortifications such as Hadrian’s Wall to manage both the administration and defense of these new Roman territories.

Many tribes sought to maintain some autonomy by forming alliances with Rome, including Prasutagus, one of eleven kings who submitted to Emperor Claudius after the Roman invasion. Prasutagus was recognized as king of the Iceni and an ally of Rome, enjoying a notably prosperous rule.

What sparked Boudica's extensive revolt?

Prasutagus, husband to Boudica, attempted to secure the future of his family and lands by naming Emperor Nero and his two daughters as heirs in his will, hoping to appease Roman authorities.

Yet, this gesture of deference was overlooked. Roman officials, led by Decianus Catus, the procurator, aggressively pursued the recovery of loans extended to Britannia’s elite by demanding immediate repayment. This aggressive collection included raiding Prasutagus’ residence, during which Boudica was flogged and her daughters were raped.

"...it turned out otherwise. Kingdom and household alike were plundered like prizes of war, the one by Roman officers, the other by Roman slaves. As a beginning, his widow Boudicca was flogged, and their daughters raped. The Icenian chiefs were deprived of their hereditary estates as if the Romans had been given the whole country. The king's own relatives were treated like slaves."

Tacitus, Annals

Not only was the property taken over by the procurator, the governor reduced the kingdom to provincial status. There may have been other abuses, as well.

Dio writes that the procurator now was demanding the return of money that had been given by Claudius to influential Britons, and that the philosopher Seneca abruptly recalled forty million sesterces that had been forced on unwilling Britons as a loan.

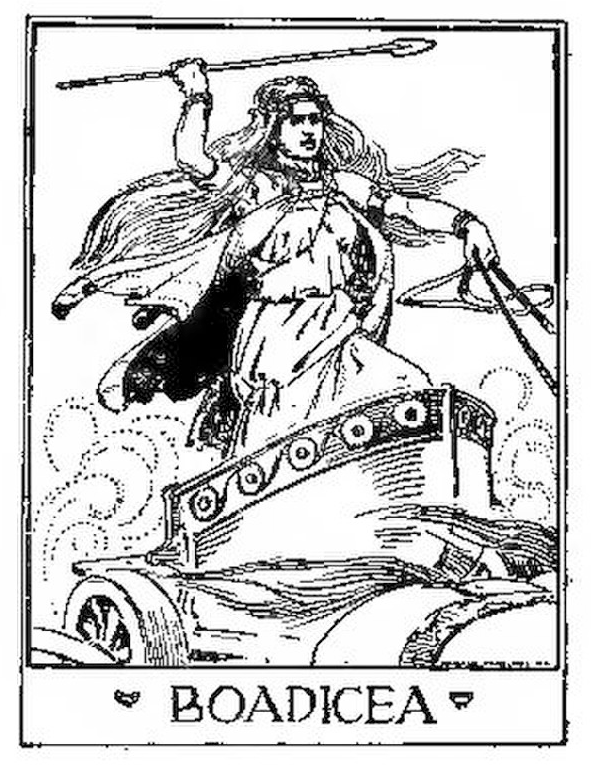

Boudica, a woman of regal lineage, was known for her imposing stature, lengthy reddish hair, and a commanding voice, all of which underscored her royal demeanor. She typically adorned herself with a golden necklace and a vibrantly colored tunic. The brutal mistreatment she and her daughters endured ignited her leadership in a significant revolt against Roman rule.

Tacitus provides the earliest and contemporary reference to Boudicca as noted in his works, Agricola and Annals, where her name appears in its original form. Meanwhile, Cassius Dio's Roman History transliterates her name as "Buduica" (LXII.2).

The name "Boadicea" first emerged erroneously from a 1624 misprint, later becoming popular through Thomas Browne's 1658 usage in Hydriotaphia. Despite variations like "Boadicia," introduced in the sixteenth century by Polydore Vergil in Anglica Historia, and subsequent adaptations in seventeenth-century English plays, the name likely closest to its Celtic roots and meaning akin to "victory" is "Boudica," aligning with Tacitus' rendition (Gildas, De Excidio Britanniae, I.6).

The rebellion

Boudica launched a revolt, rallying not only her tribe but also the neighboring Trinovantes, who shared a deep-seated resentment against Roman rule. The Roman veterans who had settled in Camulodunum (now Colchester) had displaced the indigenous inhabitants, seizing their homes and lands and reducing them to a state akin to imprisonment or slavery.

The Temple of Claudius, built there, stood as a glaring symbol of Roman domination, described by Dio as "a blatant stronghold of alien rule," and was especially despised because it was maintained by the very people it subjugated.

In the turmoil that followed, the colonists, overwhelmed by ominous signs and disarray, sought aid from the procurator. However, the limited military support dispatched from Londinium proved inadequate, leading to the swift capture and looting of Camulodunum.

The Roman troops sought refuge in the temple, but it too was overrun after two days. The Ninth Legion, already weakened and led by the rash Petillius Cerialis from Longthorpe, was caught off-guard and defeated en route. The procurator fled to Gaul in the wake of these defeats, as Boudica advanced towards Londinium.

Tacitus writes:

"Neither before nor since has Britain ever been in a more uneasy or dangerous state. Veterans were butchered, colonies burned to the ground, armies isolated. We had to fight for our lives before we could think of victory."

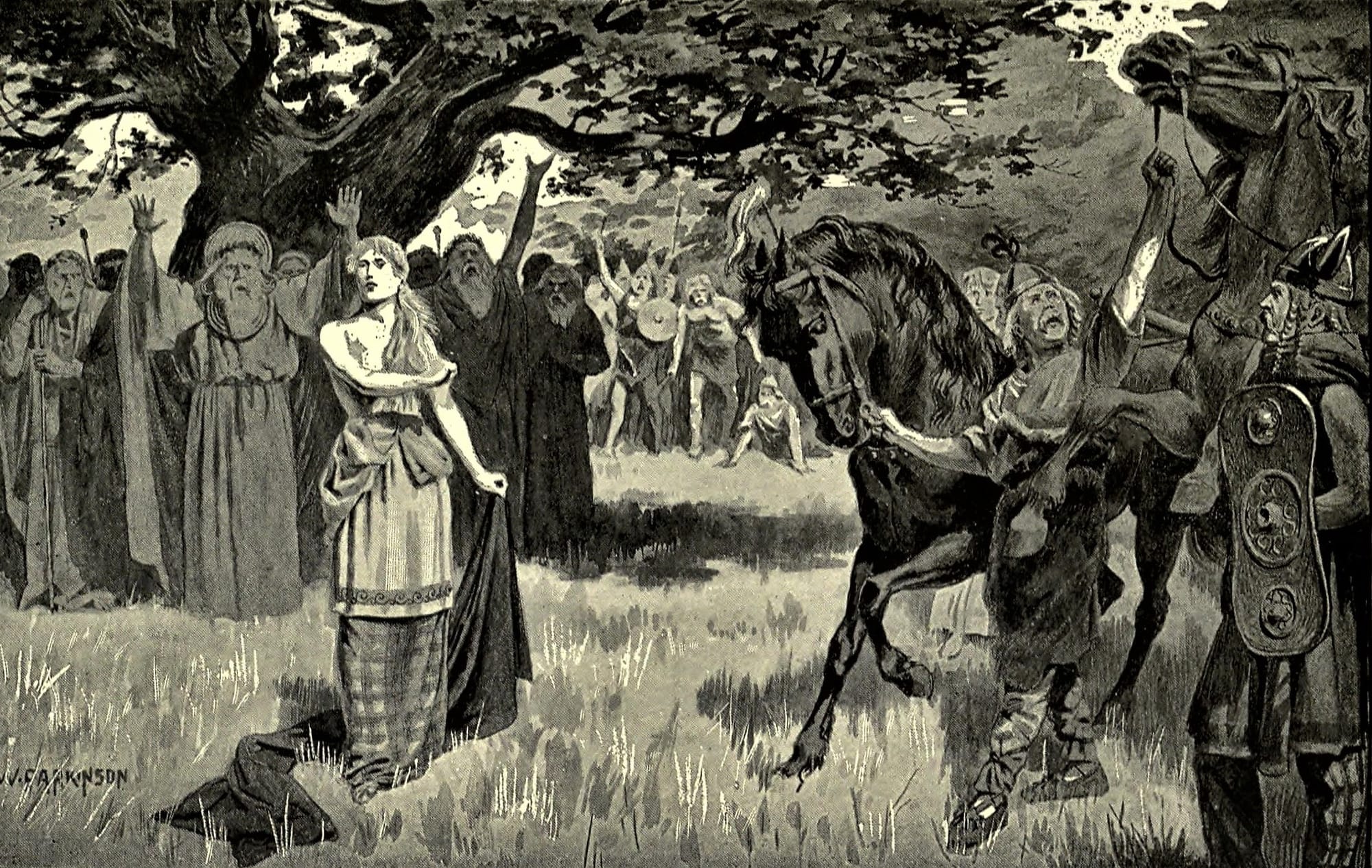

In the distant west of Britannia, Suetonius Paullinus, the region's governor, was conducting a campaign on the island of Mona (now known as Anglesey), located off the coast of northern Wales. Despite the Roman policy generally tolerating native religions, Paullinus aimed to conquer this refuge for dissidents and a major religious stronghold of the Druids.

"For it was their religion to drench their altars in the blood of prisoners and consult their gods by means of human entrails."

Tacitus reports in the Annals what happened.

"The enemy lined the shore in a dense armed mass. Among them were black-robed women with disheveled hair like Furies, brandishing torches. Close by stood Druids, raising their hands to heaven and screaming dreadful curses."

Uncertain at the spectacle, the Roman forces hesitated but then pressed forward, slaughtering all those before them. The island was garrisoned and the sacred groves of trees, their altars red with blood, cut down.

Upon hearing of the revolt, Governor Suetonius Paullinus, who was engaged in a campaign on the Isle of Mona, made a hasty return to Londinium. He brought with him Legio XIV and elements of Legio XX, while also sending cavalry ahead and issuing orders for Legio II, stationed at Exeter, to join him.

However, in a baffling decision, the commander at Exeter refused to comply. When Paullinus reached Londinium, he realized that following the defeat of Legio IX, his forces were insufficient to defend the city. Consequently, Londinium, Britain's most populous town, was evacuated, leaving those unable to flee at the mercy of the advancing rebels. The nearby town of Verulamium (modern St. Albans) experienced a similar fate, being overrun, and destroyed by Boudicca's forces.

"The natives enjoyed plundering and thought of nothing else. By-passing forts and garrisons, they made for where loot was richest and protection weakest. Roman and provincial deaths at the places mentioned are estimated at seventy thousand. For the British did not take or sell prisoners, or practice war-time exchanges. They could not wait to cut throats, hang, burn, and crucify—as though avenging, in advance, the retribution that was on its way."

Tacitus, Annals

As the rebellion escalated, Paullinus strategically gathered his forces, amassing nearly ten thousand men, which included auxiliary units from nearby garrisons. He positioned his troops at a location that provided a tactical advantage, selecting a narrow passage flanked by hills, with an open field in front and a dense forest at their back.

This site, possibly located at Mancetter along Watling Street between Mona and Londinium, where a Roman camp already existed, was chosen for its strategic merits. The legionnaires formed a tight formation at the center, flanked by auxiliary forces, with cavalry positioned at the extremities. According to historical accounts by Dio, Paullinus organized his troops into three distinct divisions for the battle.

Once again, Tacitus describes what happens:

"On the British side, cavalry and infantry bands seethed over a wide area. Their numbers were unprecedented, and they had confidently brought their wives to see the victory, installing them in carts stationed at the edge of the battlefield."

Leading her daughters, Boudica rallied her forces, driving her chariot among her tribes and shouting words of encouragement. As the Britons, crowded together in the narrow pass, tried to break into the open area, the Romans prepared their counterattack. They launched their javelins, advanced in tight wedge formations, and forcefully carved their way through the mass of rebel forces.

Dio describes the battle:

"Thereupon the armies approached each other, the barbarians with much shouting mingled with menacing battle-songs, but the Romans silently and in order until they came within a javelin's throw of the enemy. Then, while their foes were still advancing against them at a walk, the Romans rushed forward at a signal and charged them at full speed, and when the clash came, easily broke through the opposing ranks..."

The Britons initially disrupted the Roman archers with their chariot charges, but lacking protective armor, they were repelled by a heavy onslaught of Roman arrows. As the Romans launched javelins and the infantry advanced, the Britons were overwhelmed and trapped by their own logistical barriers, including wagons and dead animals that hindered their retreat.

Tacitus described the ensuing conflict as brutal, stating, "It was a glorious victory, comparable with bygone triumphs. According to one report almost eighty thousand Britons fell. Our own casualties were about four hundred dead and a slightly larger number of wounded. Boudica poisoned herself."

In the aftermath, the Roman governor Paullinus sustained military pressure, reinforcing his legions with additional troops from Germany. The region faced further hardships, including punitive actions against both hostile and neutral tribes and a famine resulting from neglected agriculture.

The political landscape shifted when Julius Classicianus became the new procurator, advocating for British resistance in hopes of a more lenient Roman governance. His efforts led to Rome recalling Paullinus, and Tacitus critiqued the subsequent governor's passive stance as a dishonorable peace.

This leniency eventually subdued the Briton resistance, marking the end of major uprisings in the region.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: