Behind Rome’s Prosperity: A Guide Not a Myth

Some of Rome’s most enduring lessons were not carved in stone but preserved in quieter forms, where method speaks softly and the world behind the empire comes into view.

Rome’s prosperity didn’t emerge from legend or luck. Beneath the marble triumphs and military conquests lay a quieter force—one built not on myth, but on method. Somewhere in the rhythm of the seasons, in the ordered work of fields and farms, a Roman writer captured a system that outlasted emperors. What he preserved was more than knowledge; it was the blueprint of how an empire fed itself, survived itself, and imagined its future.

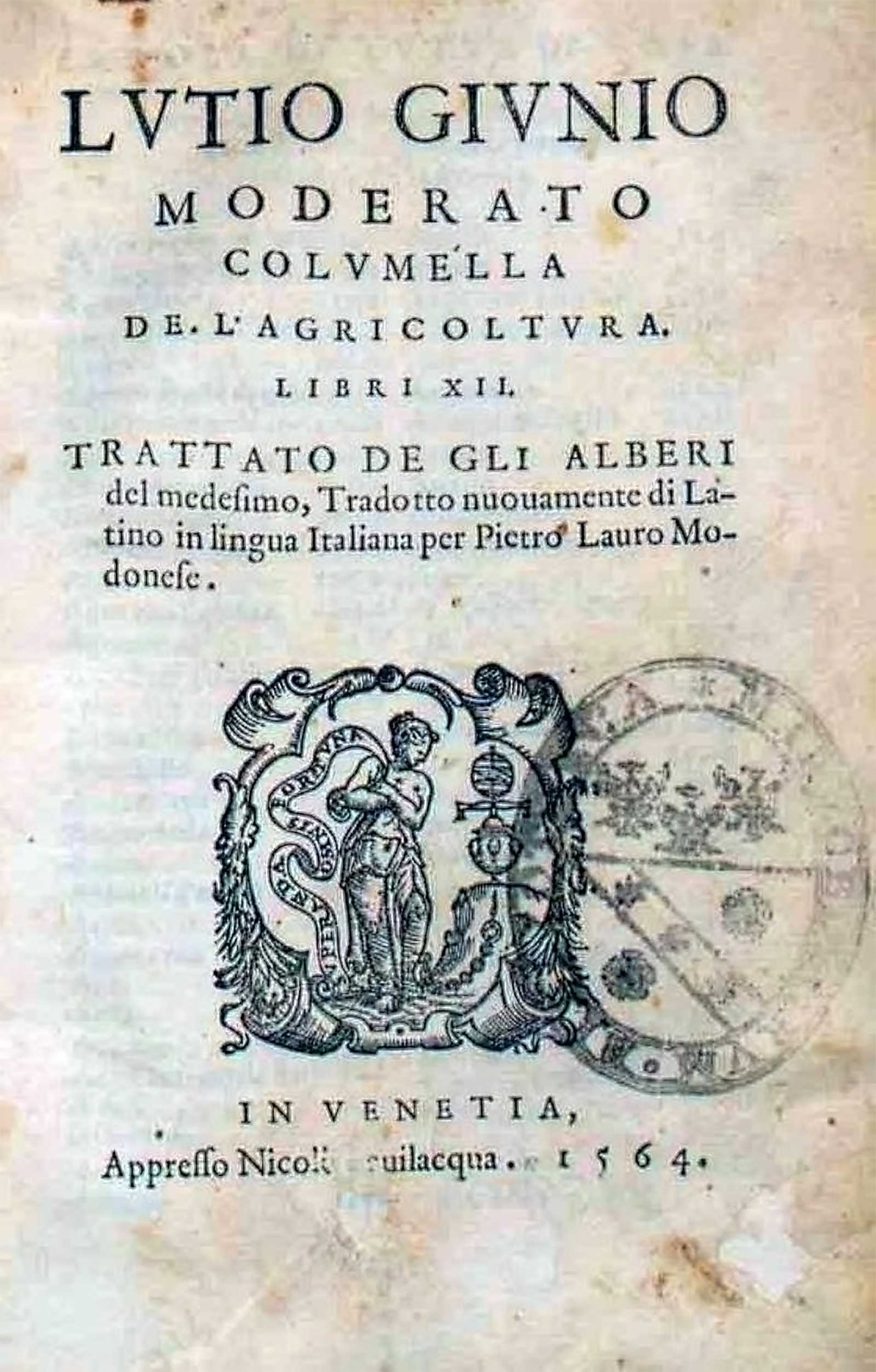

Columella’s agricultural treatise De Re Rustica attracts far less attention than its scope and interest would suggest. Even finding a reliable text is difficult: the last complete edition appeared in the eighteenth century, and the only approximation of an English version is a small selection of passages printed in Dublin in 1732.

A Roman Farm Expert Rediscovered

Almost everything known about Columella comes from his own writings. His full name is given as Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella. He lived in the same era as seneca who was born in 4 B.C. and died in A.D. 65, and, like Seneca, came from Spain. Seneca’s brother Gallio, also a Spaniard and later proconsul of Achaea, is known from the Acts of the Apostles and died in the same year. Pliny the Elder frequently cites Columella. On this basis, De Re Rustica can be placed most probably in the 60s of the first century A.D.

Columella states that he was born and spent his early years at or near Gades, modern Cádiz, in the south-west of Spain. He does not mention his parents, but he often refers to an uncle, Marcus, a keen farmer who lived in Baetica, the province where Gades was located. It is likely that part of Columella’s youth was spent in his uncle’s household.

At some stage he served with the army at Tarentum, where an inscription describes him as military tribune of the Sixth Legion Ferrata, a unit known to have been recruited at Gades. Later, while composing his agricultural works, he lived in the countryside near Rome and held estates in Latium and Etruria.

Alongside the twelve books of De Re Rustica and the De Arboribus, which survive, he also composed a work Against the Astrologers and either wrote or planned a treatise on religious ceremonies connected with agriculture.

How De Re Rustica Is Built, Book by Book

The agricultural treatise follows a clear and deliberate plan. Book I deals with the site of the farm, the nature and layout of the buildings, and the staff required to run the estate. Book II turns to agriculture in the narrower sense: the treatment of soil, ploughing, and cropping.

Books III, IV, and V are devoted respectively to fruit trees, vines, and olive trees. Book VI discusses the larger domestic animals—cattle, horses, mules, and donkeys—and includes sections on veterinary medicine. Book VII covers the smaller animals: sheep, goats, pigs, and dogs.

Book VIII moves to the care of poultry and other birds, as well as the creatures kept in fish-ponds. Book IX is devoted to bees. Book X, written in hexameters, treats gardening.

The eleventh and twelfth books form a kind of appendix and seem to have been added later. Book XI describes the duties of the bailiff; Book XII sets out the responsibilities of the bailiff’s wife and contains recipes for pickles, preserves, and preparations of wine and oil. The De Arboribus overlaps in part with Books III–V and was probably an earlier and shorter version of that material.

The Library Behind a Roman Farm Manual

De Re Rustica is a practical handbook rather than a theoretical essay. Before composing it, Columella undertook a thorough reading of agricultural writers from Hesiod down to his own day and lists about fifty such authors, many of whom are now little more than names. Among those most frequently cited is the Carthaginian writer Mago, whose agricultural work the Roman Senate had translated into Latin.

Because there was no concept of copyright in antiquity, Columella freely takes over material he finds useful from earlier Roman authorities such as Cato and Varro. Any passage that suits his purpose may be adopted and worked into his own exposition.

The language of De Re Rustica reflects the refinement and ease of Silver Latin at its best, without its more artificial tendencies. Columella rarely indulges in decorative writing; when he does, it is usually in passages attacking the moral condition of contemporary Roman society or describing the beauty of a well-kept vineyard.

He shows particular skill in explaining complex arrangements with clarity—for example, when setting out the design of a sophisticated hen-house or describing a device that holds animals in position for surgical treatment.

Virgil in the Garden: Book X in Hexameters

Columella admired Virgil deeply and quotes him often. His tenth book is written in hexameters in an attempt to echo Virgil’s manner. The chosen subject is gardening, a topic that Virgil, in Georgics IV, explicitly declares he leaves for others. Columella cannot be ranked as a major poet, but he does his best with a theme that is not naturally suited to elevated verse, even devoting lines to the cabbage.

He appears quite aware of the gap between his own achievement and his model. At one point he interrupts himself, asking why he has let his “horses” run with loosened rein on so exalted a path and acknowledging that his muse calls him back to a humbler subject, to verse of a slighter kind that might be sung by a pruner in a tree or a gardener at work in a small plot.

Serious Instruction with Fleeting Moments of Comedy

The tone of De Re Rustica is consistently earnest. The purpose is to teach, not to entertain. Yet there are passages that become unintentionally humorous. Columella advises that the farmhouse should not be built too close to a main road, otherwise too many people will feel free to drop in at mealtimes.

He recommends dried figs mixed with flour as excellent for fattening birds intended for sale. Some people, he reports, chew the figs before mixing them with the flour; this practice is rejected as unsuitable where many birds must be fed, because it is expensive to hire people simply to chew the figs, and they are likely to swallow part of the fruit themselves. The example at the same time reveals his constant concern with profit and his reluctance to endorse anything that does not pay.

“The Soil Is Exhausted”: Columella’s Reply to His Contemporaries

Columella devotes a good deal of attention to the attitudes of people in his own day. It is quite common, he says, to hear complaints that the soil is worn out and infertile. In his view, the fault lies not in the land but in the farmers, who do not take the trouble to learn how to cultivate it properly.

If someone wishes to learn to sing, dance, or speak in public, they seek out the best teacher they can find. For agriculture, however, there are neither recognized teachers nor students, even though no human being can be fed without capable tillers of the soil. The old Romans, such as Cincinnatus, farmed the land awarded to them after their victories with the same energy that they had shown in battle. By contrast, people in Columella’s time care only for luxury and pleasure. Their hands are used mainly to applaud dancers on stage; their nights are spent in feasting and drinking, and their days in sleep and gambling.

In the very country where the gods of old taught humans how best to win the fruits of the earth, Romans now live on imported grain, and farming is dismissed as a craft for which no training is required. Columella rejects this so firmly that he declares his only fear is that his last day will come before he has mastered the subject himself.

Running a Slave-Worked Estate: Bailiffs, Wives, and Work Gangs

Since Roman farming was conducted entirely by slave labor, Columella devotes substantial space to the choice and treatment of slaves. The bailiff is especially important. He should be strong and healthy, in middle age, and should have carried out heavy physical work earlier in life. Literacy is not essential if he has a good memory; in fact, a bailiff who cannot read may run the farm more profitably than an educated one, because he lacks the means to falsify written accounts and feels ashamed to ask anyone to help him do so.

He must avoid too close a relationship with the slaves under his authority and still more with outsiders. He is to keep soothsayers and witches away from the farm, since they disturb the minds of the ignorant. He should only leave the property to make purchases or sales or to acquire some useful knowledge for his work.

He is instructed to maintain roughly twice as many tools in reserve as are currently in use, because the value of work lost when tools are lacking far exceeds the cost of keeping spares. He should always eat at the same table and from the same food as the workforce so that he can be sure they are fed properly.

Columella also speaks about the wife of the bailiff. She should be young but not too young, and strong enough to endure hard work. Her appearance should be neither ugly nor very beautiful, so that her husband is neither repelled into seeking company elsewhere nor tempted to idle around the house. She must supervise everything indoors and ensure that her husband has as little domestic occupation as possible, because he needs to go out early to the fields with the other slaves and return only at sunset.

As for the farm slaves themselves, Columella states that he talks to them more often and more freely than to town slaves, even joking with them from time to time, because friendliness lightens toil. He consults them about their work to gauge how much they understand. Justice in treatment and attention to their complaints are essential. Those who incite others to revolt must be punished promptly, while good conduct should be recognized and rewarded.

Tasks must be matched carefully to character. Shepherds should be diligent and conscientious because they work alone, without constant supervision; great physical strength is less important. Ploughmen should have a loud voice and a fierce expression to command respect from the oxen but ought to be terrifying rather than cruel. Workers in vineyards should be broad-shouldered and muscular rather than tall; their trustworthiness is less crucial, since they are continually overseen.

Unruly slaves are often intelligent, and vineyards, which require skill, can therefore be tended by slaves in chains. Nonetheless, Columella insists that there is nothing an honest man of equal intelligence will not do better than a rogue.

Slaves are to be assigned to one kind of work only and organized into gangs of ten, with competition encouraged between the gangs. Female slaves who bear many children should be rewarded: those who have borne three sons are to be excused from heavy labor, while the mothers of four or more sons are to receive their freedom.

Gods, Festivals, and Everyday Superstitions on the Farm

When the owner visits the estate, he must look over all the buildings, fields, livestock, and equipment, and judge the discipline of the slaves. Yet his first action should be to pay respect to the household gods. Religious observance is treated as a serious matter, and proper attention to rituals is portrayed as having a favourable effect on the farm’s yield.

A long chapter is devoted to which tasks may or may not be carried out on religious festival days. Among the prohibited actions are hauling felled trees, breaking new ground, sowing seed, cutting hay, gathering the grape harvest, and shearing sheep—unless a puppy has first been sacrificed.

Columella also records a number of beliefs that, even by ancient standards, appear superstitious. Eggs to be set under hens are always to be in odd numbers. The pains of oxen can be cured, it is claimed, by the sight of swimming birds, especially ducks. The plant lungwort, a remedy for cattle, should be picked only with the left hand and before sunrise if it is to work.

To keep shrew-mice from harming an ox, one may enclose a living shrew-mouse in potter’s clay and hang it round the animal’s neck. Such rules can seem absurd, but a comparison is drawn with the quite common reluctance to sit down thirteen at a dinner table, which is hardly less irrational.

Dogs as Essential Guardians of the Estate

Among a farmer’s early priorities should be the purchase of a dog. Dogs guard the farm, its produce, and its flocks. Calling dogs “dumb animals” is declared completely wrong, since their loud bark is the very thing that warns of thieves and wild beasts.

The shepherd is advised to prefer a white dog so that it can be distinguished clearly from the wild creatures it attacks. The dog that guards the farmyard should preferably be black, since a dark animal appears more alarming and is less visible at night. Dog names should be short and, ideally, two syllables long. Both Greek and Latin names are suggested: for male dogs, for example, Ζκίρῃα (“Puppy”), Λάκων (“Spartan”), Ferox, and Celer; for bitches, Σπουδή (“Zeal”), Ἀλκή (“Courage”), Ῥώμη (“Strength”), Lupa, Cerva, and Tigris.

It is also stated that cutting a dog’s tail prevents it from developing rabies, although no explanation is offered. Pliny later repeats this view and explicitly gives Columella as his source.

At the close of the twelfth book, Columella remarks that, now his task is complete, it seems appropriate to address any future readers who may concern themselves with such matters. The range of possible topics is described as virtually endless, yet he has chosen to set down only those points that seemed most essential. Practical knowledge of all things, he says, has not been granted even to the grey-haired. Even the men reputed to be the wisest of mortals are thought to have known many things, but not everything.

In later centuries his work did not always receive close attention, but there were important admirers. Milton, in his Tract on Education, speaks highly of Columella and recommends that boys should read him early in their studies. The subject matter is described as straightforward; if the language is demanding, so much the better, since it poses a difficulty not beyond their years and can become a means of encouraging them, and of equipping them one day to improve the cultivation of their own country. ("Columella and His Latin Treatise on Agriculture" by E. S. Forster)

While the agricultural treatise presents Columella as a practical writer shaped by experience, training, and a strong sense of the farmer’s responsibilities, the work also relies on a carefully constructed literary framework. The opening address to Publius Silvinus, which at first appears to be a conventional dedication, plays a far more significant role in the structure of the books.

This figure becomes an essential device through which shifts of topic, criticisms of contemporary farming, and contrasts between genuine expertise and fashionable theory are expressed, revealing an additional layer of intention beneath the surface of the manual.

Silvinus as a Deliberate Literary Device

The agricultural treatise opens by addressing Publius Silvinus, following the tradition of framing technical instruction as if directed to a particular person. His name appears twenty-six times, each use signalling a calculated shift in topic through rhetorical praesumptio, anticipating what Silvinus might raise next.

He is invoked formally at the opening of each book, typically with his full name, especially when placed in the company of notable figures. The omission of the praenomen at the start of Book 5 is treated as an intentional stylistic choice.

Although presented as a “country-man and neighbour,” Silvinus is likely fictitious. His role extends beyond that of addressee: he represents qualities associated with contemporary agricultural decline — the fashionable landowner who purchases an estate for prestige, depends on a vilicus, spends little time on the land, and values literary erudition over practical skill. He embodies the “book farmer,” aligned with authorities whose advice is described as uelut inlectus nimio fauore priscorum de simili materia disserentium falso credidit (“as if captivated by the excessive favour shown to the ancients who wrote on the same subject, he believed them wrongly”).

Silvinus as Foil and Personification of Agricultural Problems

Silvinus appears as a visitor to the farm, encouraged to attest to its efficiency. He reads the treatise sequentially, and his questions allow the author to return to earlier points and strengthen his arguments. Though not wholly ignorant and owner of his own farm, he reflects the absentee master who seeks intellectual approval more than agricultural competence, set in contrast with the ueteres Romani (“the ancient Romans” ) who worked their own land.

He stands within a wider shift in Roman farming: the rise of large estates, the prestige tied to rural ownership, and the increasing detachment of proprietors from the land. Estate management had become impersonal and financially driven, reflected in the criticism of using citizens occupatos nexu et ergastulis (“bound by debt and confined in work-gangs”).

Silvinus thus becomes a composite figure that encapsulates these tendencies. This also explains the tone of Book 5, where Silvinus criticises omissions, prompting a rebuttal of exhaustive and abstract approaches. The response insists on practical experience, followed by a geometric digression introduced with a request for indulgence for any scientific errors — a gesture coloured by irritation.

Silvinus is connected with the studiosi, not students of the author but newcomers to fashionable intellectual agriculture. They offer both praise and criticism, uncertain in judgment. Their arguments are described as quae utroque reprehensio ambiguam magis habet aestimationem quam ueram (“a criticism from both sides that has a judgment more uncertain than true”). Their anticipated objections are dismantled through rhetorical praesumptio.

Practical Knowledge Against Abstract Theory

The treatment of stock-raising shows the tone applied to these critics. What might seem like hesitation is revealed as sarcasm, especially in the use of prudentes. Stock-raising and agriculture are depicted as inseparable, contrary to the purist view that separates them. Older Roman practice acknowledged their unity. The emphasis falls repeatedly on experience, captured in the phrase “Experto mihi crede, Siluine.” (“Trust me, Silvinus, for I speak from experience”)

Silvinus’ objections allow a contrast between practical farming and the pedantic classifications favoured by intellectual agriculturalists. By setting out his positions and countering them with more grounded responses, the treatise reveals itself not only as instruction but also as an indictment of the habits and assumptions shaping contemporary agriculture. ("Columella the Reformer" by Peter D. Carroll)

The portrait that emerges is not only that of a skilled agricultural writer but of a work shaped by structure, intention, and a quiet firmness of judgment. Technical instruction, social observation, and literary design are woven together in a treatise that reaches beyond its immediate purpose. Through its careful organisation, its appeals to experience, and its use of figures such as Silvinus, the text reveals the practices, expectations, and tensions that defined Roman farming at a moment when tradition and fashion met on the same ground.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: