Bacchanalia: Rome’s Forbidden Festival

The Bacchanalia, also known as Bacchanal or Carnival, were Roman festivals honoring Bacchus, inspired by elements of the Greek Dionysia.

Bacchanalia celebrations, which spread widely across central and southern Italy, were closely linked to the Roman cult of Liberalia, dedicated to the deities Liber and Libera (also known as Proserpina). The cult likely reached Rome around 200 BC. However, as with many Greco-Roman mystery religions, the specific rituals remain largely unknown.

Over time, as the Bacchanalia grew in popularity, the Roman Senate began to perceive the cult as a threat to political stability, believing it could be used to incite rebellion. To protect their authority, they sought to suppress the Bacchanalia, fearing it might foster dissent against the Senate's control.

Livy, writing approximately 200 years after the Bacchanalia, provides a sensational and vivid account of the events, describing the rites as chaotic, with frenzied rituals, violent sexual initiations, and a conspiracy involving people from all social classes. According to Livy, the cult was a dangerous instrument of rebellion against the state, and he claims that around seven thousand followers were arrested, with most of them executed.

Modern scholars, however, are more skeptical of Livy's dramatic portrayal and question whether his descriptions of the Bacchanalia were exaggerated.

Bacchanalia, by Peter Paul Rubens, Public domain

The Roman Senate responded by legislating against the Bacchanalia in 186 BC, imposing restrictions on the size, organization, and priesthoods of the rites under the threat of death. This legislation may have been more about asserting the Senate's civil and religious authority following the crises of the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) than about the lurid rumors Livy describes.

Over time, the Bacchanalia were likely merged with the Liberalia festival, and Bacchus, Liber, and Dionysus became virtually synonymous by the late Republic, with their mystery cults continuing into the Roman Imperial period.

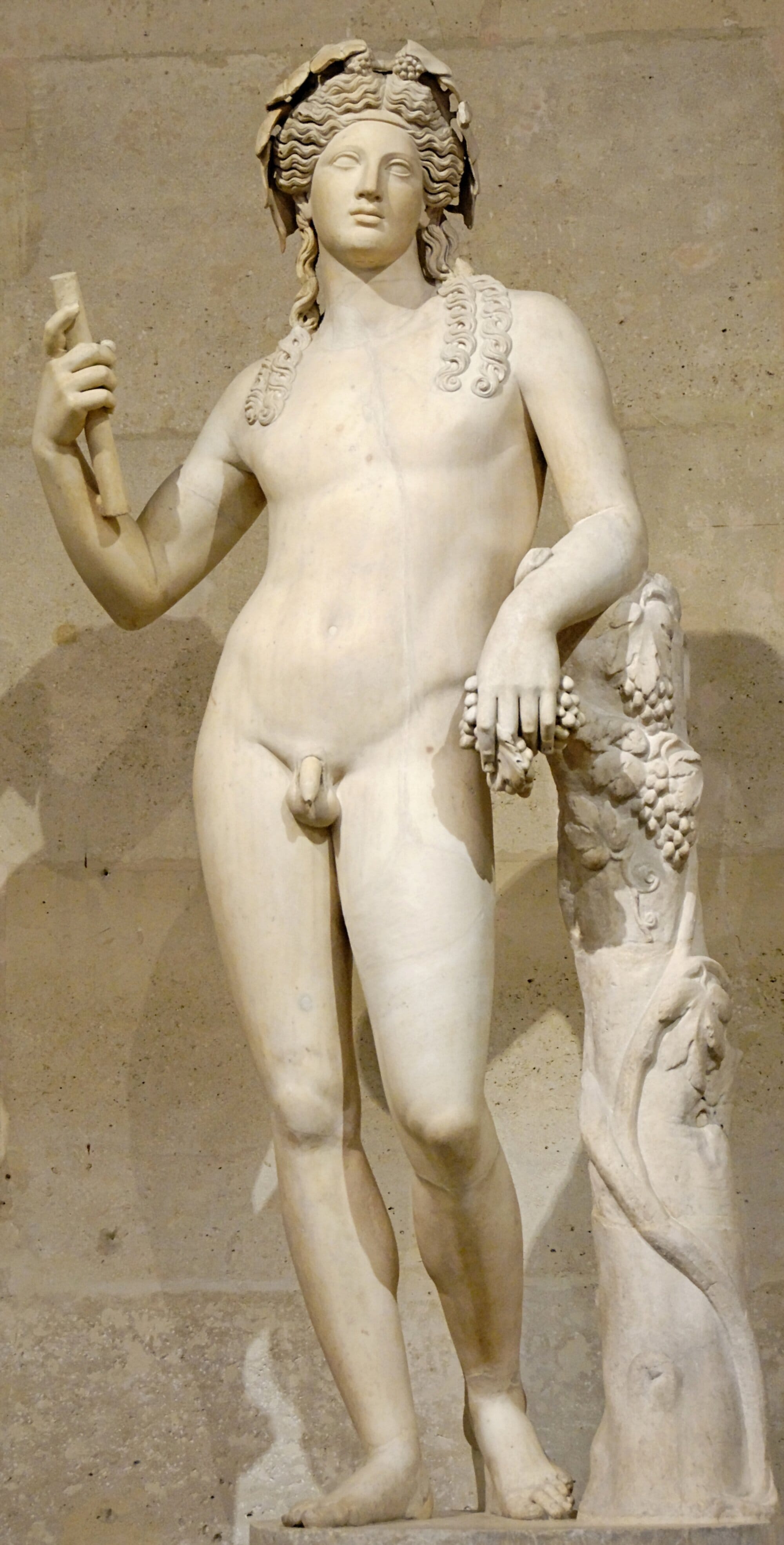

The Cult of Bachus (Dionysus)

Livy, in his account of the Bacchanalia affair of 186 BCE, depicted the cult of Bacchus as a "contagione morbi," or a polluting sickness that endangered Roman society. The Senate responded with a large-scale purge, reportedly persecuting over 7,000 followers of the cult and banning all forms of non-traditional Bacchic worship. Livy’s narrative presents this as a definitive resolution to the perceived threat.

However, the story did not end there. Despite the Senate's efforts, the Bacchic rites persisted. Julius Caesar, during the decline of the Roman Republic, reintroduced these ecstatic rituals to gain favor with the plebeians. By the late second century CE, Bacchus’ cult had not only survived but thrived, spreading to both the lower and upper classes.

Although the Bacchanalia scandal has led scholars to view Dionysiac cults as marginalized we can see that these mystery cults were far more integrated into Roman society than previously believed, particularly in the Roman East. Epigraphic evidence shows that these cults interacted with the public sphere and were seen positively by both initiates and broader communities. Rather than existing on the fringes, Dionysiac associations contributed visibly to the public good.

Dionysiac cults, or Dionysiac mystery cults, were private religious associations focused on the worship of the god Dionysus (also known as Bacchus or Liber). These groups gathered for the performance of rituals, often involving ecstatic elements, in honor of the god, who was associated with wine, revelry, and divine madness. Some Dionysiac associations, like the technitai, were professional guilds of artists, while others were devoted to mystery rituals aimed at spiritual or soteriological ends.

Mystery cults, including those of Dionysus, are often portrayed as marginal, but evidence suggests that Dionysiac cults were more integrated into public life than previously thought. Inscriptions show that these religious associations interacted significantly with local communities and contributed to civic life, particularly in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire. They were respected and viewed positively by the wider society. In terms of structure, "mystery" versions of Dionysiac cults can be distinguished by their initiation process, indicated by terms like mystai (initiates) and offices like the hierophant (revealer of sacred things).

The terminology used for the god also changed over time, with Dionysus, Bacchus, and Liber becoming somewhat interchangeable, as Romans absorbed foreign religious practices.

Antinous, Emperor Hadrian’s favourite, as Dionysus-Osiris. Credits: Ajwm8103, CC BY-SA 4.0

Franz Cumont, an early 20th-century scholar, classified these mystery cults as "Oriental" religions, suggesting they represented a shift from public to private forms of religiosity, ultimately leading to the triumph of Christianity. This view, although outdated and oversimplified, persists in some scholarship, where private religion is sometimes seen as more personal and authentic compared to civic religion.

Thus, while Dionysiac mystery cults are often portrayed as secretive and marginal, they played a more active and accepted role in Roman public life than earlier interpretations have suggested. (The Public Lives of Private Cults: Dionysiac Associations in the Roman East, by Sarah L. Veale, The University of Toronto)

The Bacchanalia Affair

The Bacchanalia, as already mentioned, were Roman festivals celebrating Bacchus, the Greco-Roman god of wine, freedom, and ecstasy. These rites were based on the Greek Dionysia and the mysteries associated with Dionysus, and were likely introduced to Rome around 200 BCE through the influence of Greek colonies in southern Italy and from Etruria, Rome’s neighbor to the north.

Scholar Tenney Frank theorized that the Bacchic worship may have been brought to Rome by prisoners captured from the Greek city of Tarentum during Rome's war with Carthage in 209 BCE. Like many mystery cults, the Bacchanalia were secretive, and initiates were sworn to silence about the rites. What is known about them comes from literary, dramatic, and artistic sources.

However, the Bacchanalia differed from other mystery cults by having two distinct forms of celebration.

- The first type was public and involved theatrical performances, such as tragedies or satirical plays. These public displays of the Bacchanalia did not become common until centuries after the notorious Bacchanalia Scandal.

- The second type of Bacchanalia, which gained attention during this scandal, involved secret, frenzied, and unrestrained rites, including orgiastic celebrations where participants indulged in sexual freedom as a way of connecting with Bacchus.

Livy claims that the earliest form of the Bacchanalia was an exclusive, daytime festival for women, held three times a year. However, in Etruria, a "Greek of humble origin," knowledgeable in sacrifices and divination, introduced a nocturnal version, which included wine and feasting, attracting both men and women to participate. Livy describes the nighttime Bacchanalia as a breeding ground for immoral activities, suggesting that it was a setting where sacred murders and other crimes could occur undetected due to the loud festivities and music, making it easier to hide criminal acts.

However, traditional Greek religious rites typically involved singing hymns, dancing, sacrifices, and libations, practices that would likely not have changed when the Bacchic cult transitioned from Greece to Rome.

“…The ignoble Greek came first into Etruria as a dabbler in sacrifices and as a seer, possessing none of those many arts which the most learned of all the Greek people brought to us for cultivation of mind and body; nor was he the sort who, after his ritual was uncovered by openly proclaiming both the profit and discipline of his religion imbued their minds with error by openly proclaiming both the profit and discipline of his religion, but he was a priest of secret rites performed at night.

These were the beginning rites, which at first were shared with only a few, but then began to be known by men and women. Pleasures of wine and feast were added to the ritual, so that the minds of many might be enticed.

When the wine had set fire to their souls, both the night and the mingling of men and women, old and young, had destroyed every sense of shame from the majority, first the corruptions of every kind began to happen, since each one was having a pleasure for himself, which suited his nature of prone lust.

There was not only one form of vice, namely the shameful meetings of noble men and women, but false witnesses also escaped out of the same office by false proofs and testaments and evidence; there were poisonings and internal murders from the same place, so that indeed sometimes not even the bodies remained for burial.

Many things were dared by craft, the majority by violence. The violence was concealed because, amid the wailing of the small drums and the noise of the cymbals, no voice of those crying for help was able to be heard clearly among the debauchery and the murders.”

Livy Against the Worshipers of Bacchus

Central to Livy's account is the story of Hispala Fecenia, a freedwoman, who exposed the cult’s rituals to protect her lover, Publius Aebutius. Her warnings eventually reached the consul, Postumius, and led to a Senate-led crackdown.

Livy’s recounting is dramatic and colored by moral alarm, likely influenced by earlier traditions of Roman historians, such as Aulus Postumius Albinus and Piso, who documented the event before him. Over time, the story likely accumulated additional details and embellishments through retelling by various historians before Livy penned his version.

“A well known harlot, a freedwoman named Hispala Faecenia, not worthy of the occupational wealth to which, while a slave woman, she had been accustomed to, preserved herself in the same way even after she had been manumitted.

Since they were neighbors, a relationship to this woman with Aebutius began, damaging neither to the young man’s financial matters or reputation: for he had been freely loved and desired, and, with his provisions poorly supplied by all his family members, he was sustained by the generosity of the courtesan.

Because she was captivated by the intimacy, she proceeded so that after the death of her patron, because she was under the control of no one, and having petitioned the tribunes and the praetor for a guardian, when she made her will, she instituted Aebutius as her sole heir.”

Despite Livy's vivid and shocking portrayal of the Bacchic cult, modern scholars view his account with skepticism, considering it more of a moralizing and dramatized narrative than a fully accurate historical account. (Silencing the Revelry: An Examination of the Moral Panic in 186 BCE and the Political Implications Accompanying the Persecution of the Bacchic Cult in the Roman Republic, by Heather Moser)

Livy’s account of the Bacchanalia is the only narrative we have about these events, but the reliability of the content has been questioned due to Livy's moral biases. His depiction of the Bacchanalia as a "workshop of all kinds of evil" likely reflects his personal views and may not accurately represent the rituals. In other parts of the Mediterranean world, Bacchic rites were not associated with debauchery, forgery, or murder. More likely, the rites included common elements such as singing hymns, dancing, processions, and sacrifices.

Livy's Ab Urbe Condita blends annalist, literary, and rhetorical elements, which impacts the reliability of the text. While his narrative is vivid and detailed, it mixes reliable annalistic records (focused on annual events like elections and consular duties) with more dramatic literary sources. Livy’s “Postumius narrative”, is considered more reliable as it is based on an annalist source, while his “Hispala narrative” is more literary and dramatized.

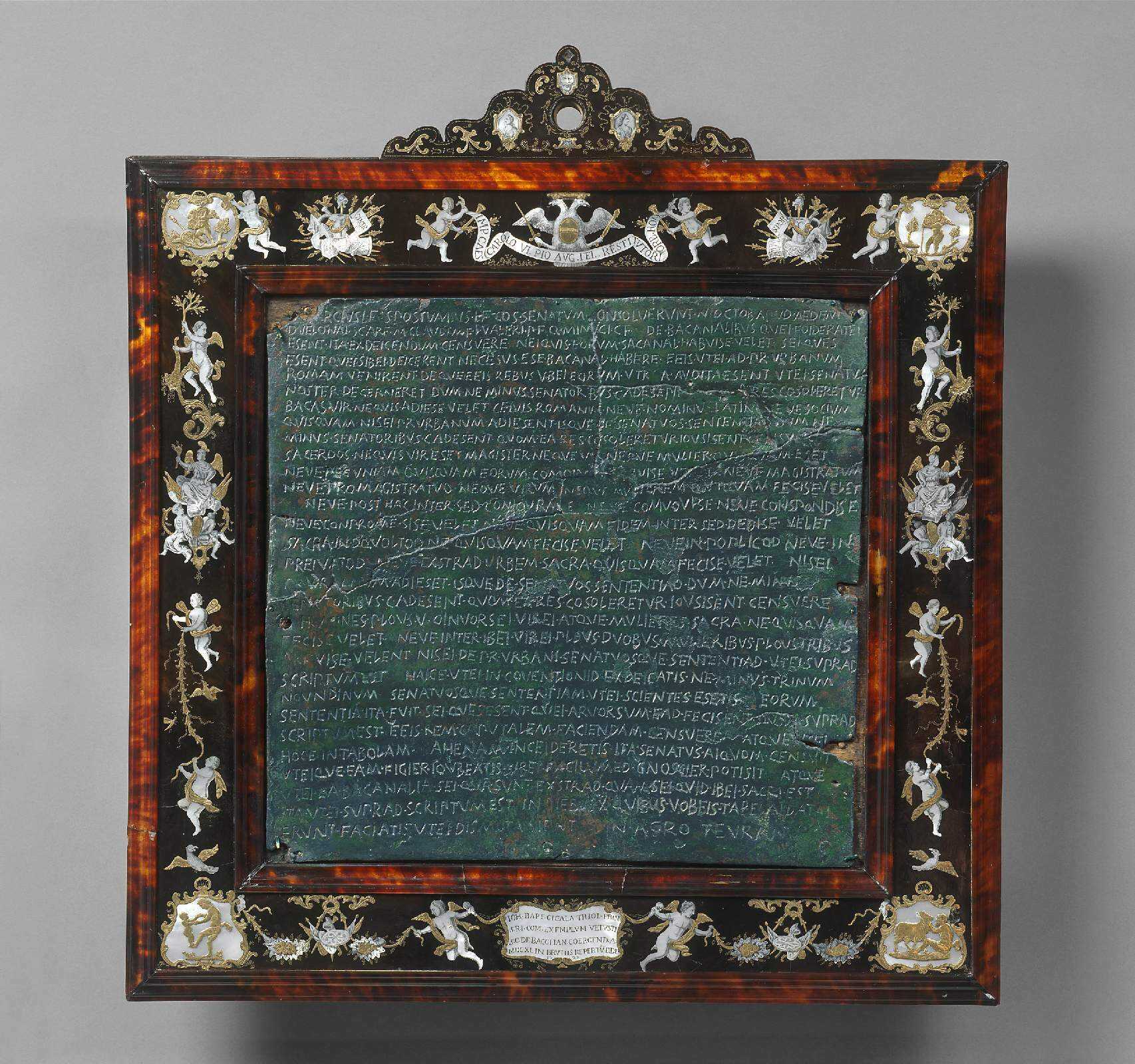

The Senatus Consultum de Bacchanalibus

In 186 BCE, the Roman Senate passed the Senatus Consultum de Bacchanalibus, a law against the cult of Dionysus, the Bacchanalia and initiated what was then the largest systematic persecution of a religious group in Europe, targeting the worshippers of Bacchus.

Livy, in the 39th book of Ab urbe condita, claims that 7,000 individuals fell victim to the Senate's campaign, with the majority being executed. This action caused widespread fear both in Rome and beyond, leading to numerous suicides and mass flight from the city. Cicero adds that the measures included military operations, giving the persecution a crusade-like appearance. The suppression lasted for five years, ultimately reducing the Bacchic cult to a smaller, more controlled group subject to strict regulations.

This event marked the first significant interference by the Roman Senate in the religious affairs of its allies, or foederati. The persecution demonstrates that polytheistic societies, like Rome, were fully capable of carrying out systematic religious exclusion and suppression, challenging the notion that such practices were unique to monotheistic cultures. (Livy and the Bacchanalia, by Dwayne Meisner)

"The Consuls Quintus Marcius, the son of Lucius, and Spurius Postumius, the son of Lucius, consulted the senate on the Nones of October (7th), at the temple of the Bellona. Marcus Claudius, son of Marcus, Lucius Valerius, son of Publius, and Quintus Minucius, son of Gaius, were the committee for drawing up the report.

Regarding the Bacchanalia, it was resolved to give the following directions to those who are in alliance with us:

No one of them is to possess a place where the festivals of Bacchus are celebrated; if there are any who claim that it is necessary for them to have such a place, they are to come to Rome to the praetor urbanus, and the senate is to decide on those matters, when their claims have been heard, provided that not less than 100 senators are present when the affair is discussed.

No man is to be a Bacchantian, neither a Roman citizen, nor one of the Latin name, nor any of our allies unless they come to the praetor urbanus, and he in accordance with the opinion of the senate expressed when not less than 100 senators are present at the discussion, shall have given leave.

No man is to be a priest; no one, either man or woman, is to be an officer (to manage the temporal affairs of the organization); nor is anyone of them to have charge of a common treasury; no one shall appoint either man or woman to be master or to act as master; henceforth they shall not form conspiracies among themselves, stir up any disorder, make mutual promises or agreements, or interchange pledges; no one shall observe the sacred rites either in public or private or outside the city, unless he comes to the praetor urbanus, and he, in accordance with the opinion of the senate, expressed when no less than 100 senators are present at the discussion, shall have given leave.

No one in a company of more than five persons altogether, men and women, shall observe the sacred rites, nor in that company shall there be present more than two men or three women, unless in accordance with the opinion of the praetor urbanus and the senate as written above.

See that you declare it in the assembly (contio) for not less than three market days; that you may know the opinion of the senate this was their judgment: if there are any who have acted contrary to what was written above, they have decided that a proceeding for a capital offense should be instituted against them; the senate has justly decreed that you should inscribe this on a brazen tablet, and that you should order it to be placed where it can be easiest read; see to it that the revelries of Bacchus, if there be any, except in case there be concerned in the matter something sacred, as was written above, be disbanded within ten days after this letter shall be delivered to you.

In the Teuranian field."

The inscription of Senatus Consultum de Bacchanalibus

To understand the Bacchanalia's suppression, we must consider the broader political and cultural context. The period marked Rome’s increasing exposure to Greek culture, particularly after the Second Macedonian War. Greek customs, including the Bacchanalia, were met with both acceptance and resistance in Rome, with Greek literature, philosophy, and religion becoming more influential. The Hellenization process was still in its early stages but advanced after Rome's wars with Macedonia and Antiochus III.

The suppression of the Bacchanalia in 186 BCE can be viewed within the context of Roman political opposition to foreign influences and the Roman concept of coniuratio (conspiracy), which framed the Senate’s decision to outlaw the Bacchanalia. The Bacchanalia represented just one of the many Greek cultural elements making their way into Roman life during this period of cultural exchange, and political transformation.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: