Who were the Plebeians in Ancient Rome? The Plebs Urbana of the Roman Republic

The plebeians made up the majority of the population in he Roman Republic. They were the common working class of the time.

The plebeians were a significant social class in ancient Rome, encompassing most of the population who were not part of the aristocratic patrician class. The exact origins of the term "plebeian" are uncertain, but it might be connected to the Greek word "plethos", which means masses.

In Latin, "plebs" is a singular collective noun, with the genitive form being "plebis". The plebeians were not a uniform social group; those living in the city and belonging to the four urban tribes are often referred to as "plebs urbana", whereas those residing in the countryside and part of the 31 smaller rural tribes are sometimes called "plebs rustica".

What was the structure of the early Roman society?

Citizens

To be a Roman citizen, one had to be born in the city of Rome to parents who were already Roman citizens. This status conferred numerous privileges, including the right to participate in political life and exemption from certain taxes. Within the population of Roman citizens, there were further subdivisions that determined additional rights and privileges.

Non-citizens

Non-citizens in ancient Rome were individuals who were not born in Rome. By the late Republic, thousands of non-citizens lived in the city, including people from neighbouring states and other countries.

When Rome conquered other countries, the inhabitants of these areas became known as provincials. Slaves were also considered non-citizens. Unlike Roman citizens, non-citizens had to pay taxes, although they were allowed to vote in elections.

Plebeians

The remainder of Roman society was made up of plebeians. Although plebeians were citizens of Rome, they were not descendants of the city's original founding families and did not have the right to participate in politics or hold roles in political and religious institutions.

However, they were permitted to vote in the comitia curiata. Due to the patrician ban on intermarriage with plebeians, it was rare for plebeians to ascend to patrician status. On occasion, plebeians married into patrician families, but this was primarily a political strategy used during the late Republic.

Despite not coming from noble backgrounds, many plebeians accumulated significant wealth, working as craftsmen, farmers, and traders. By the late Republican period, a substantial number of wealthy plebeians, known as equites (Latin for knights or horsemen), demanded the right to run for public office. The equites capitalized on Rome's expanding empire, building prosperous importing, and exporting businesses between Rome and its provinces. These demands for political influence led to conflicts with the patricians.

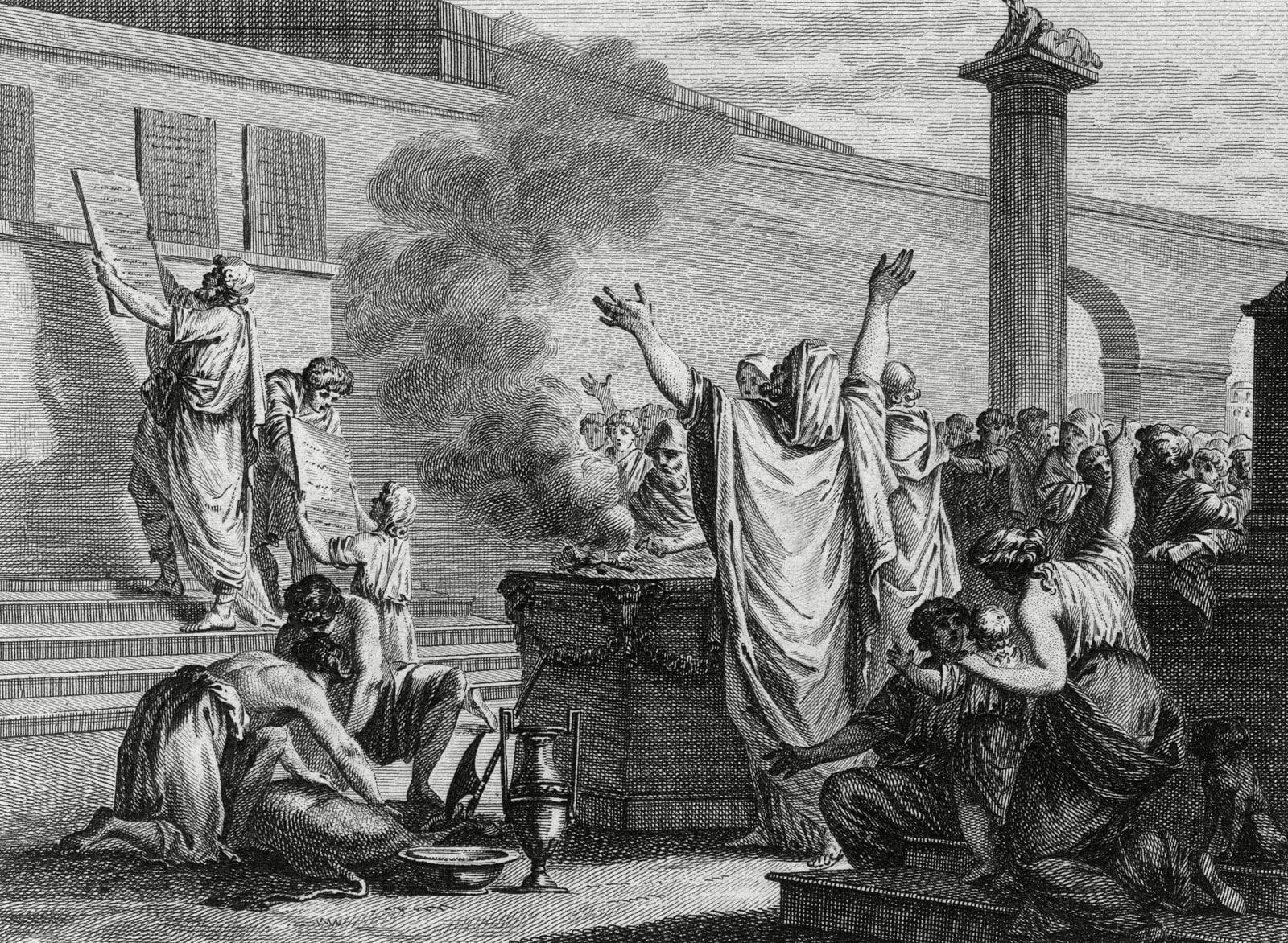

There were numerous disagreements between plebeians and patricians over political power. Many plebeians sought a voice in the governance of Rome. In 494 BC, plebeians threatened to leave Rome, prompting the Senate to allow them to establish their own council and elect representatives called tribunes. The tribunes were granted the power to veto any political changes that could harm the plebeians.

Over time, plebeians won the right to run for political office, with the first plebeian consul elected in 336 BC. By 287 BC, all decisions made by the plebeian council were required to become law.

Patricians

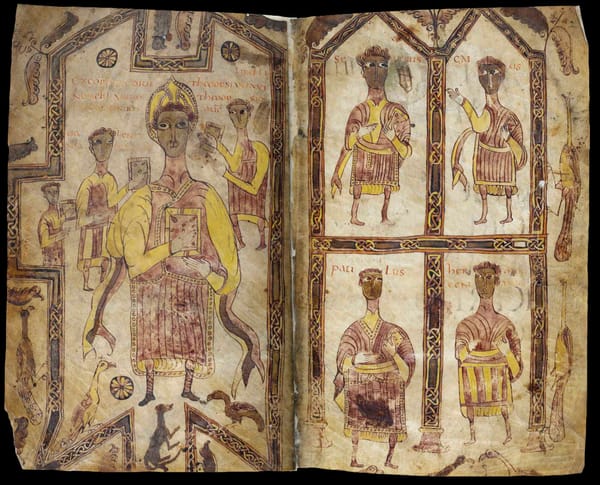

Patricians were an elite group who owned extensive land and were of noble descent, giving them a privileged status in the state. To be a patrician, one had to trace their ancestry back to the original clans that settled the Seven Hills of Rome. Patricians held significant control over the state by monopolizing authority. They dominated the Senate and the consulship, and had control over the assembly. Additionally, patricians controlled the state's religious institutions through their dominance of the two major priestly colleges—the Augurs and the Pontifices. Religion and politics were deeply intertwined, with religion playing a crucial role in political decisions.

Patricians also controlled the legal system, overseeing all criminal and civil law. Since the legal code was unwritten and only patricians could administer and interpret it, they could manipulate the law to their advantage. To maintain a strict social divide, patricians were prohibited from intermarrying with plebeians. Patrician marriages, known as confarreatio, were officiated by the pontifex maximus and the flamen Dialis (priest of Jupiter), entitling the bride to a share of possessions and religious duties.

Patricians owned large tracts of land and could afford to lease public land (ager publicus) from the state. Unlike plebeians and foreigners, who engaged in industry and trade, patricians abstained from these activities. They also dominated the highest ranks of the military, particularly the cavalry. Military service was based on property qualifications, as soldiers were responsible for their own equipment. Patricians, with their wealth, could easily keep their properties productive while away on campaigns.

Patrons

An essential system for addressing the power and privilege disparities between patricians and plebeians in ancient Rome was the patron-client relationship. This tradition, established in the early Republic, involved groups of patricians (patrons) agreeing to protect groups of plebeians (clients) in return for political and personal assistance.

Patrons provided their clients with land, food, legal assistance, and protection. In exchange, clients would vote for their patrons in political matters, support them in public life, and follow them into war.

Women

In ancient Rome, women were never considered equal to men and lacked the right to vote or participate in politics. Among women, citizen patrician women occupied the highest social rank. These women enjoyed the most independence and freedom, living off their families' wealth and socializing during the day and night, with household chores managed by servants and slaves.

In contrast, most plebeian women did not have the luxury of servants and slaves. They typically performed their own housework with the help of their daughters and female relatives. Some plebeian women also worked, either assisting their husbands in their jobs, or working independently.

Slaves

The lowest group in Roman society were the slaves. As Rome's empire expanded, bringing more cities, countries, and civilizations under Roman rule, the number of slaves in Rome increased significantly. Slaves could be men, women, or children and had no rights or freedom. They were bought, sold, and treated as property, forced to perform menial and laborious tasks.

Educated slaves often served as tutors, doctors, and librarians. Healthy and strong slaves were put to work in construction and agriculture, while women and children typically served as domestic servants. Troublesome slaves were sent to quarries and mines, where they were often worked to death.

By the late Republic, Rome had become heavily reliant on slaves for its labor force.

Illustration: Midjourney

The life of the plebeians

Plebeians who were clients of a patrician received land from them in exchange for political and economic support. They typically resided in multi-story buildings known as insulae, which functioned as apartment complexes housing numerous families. These structures generally lacked modern amenities such as running water and heating systems. Insulae were also devoid of bathrooms, with residents commonly using pots for their sanitary needs. The quality and condition of these buildings varied considerably.

Plebeian men typically wore tunics made from wool felt or other inexpensive materials, secured with a belt at the waist, and paired with sandals. Women, on the other hand, wore a long dress known as a stola. The risk of extreme poverty among plebeians was significant, especially since they often had to leave their land unattended to fulfill military obligations. This absence frequently led to debt, and the debt laws (unwritten at the time) were extremely harsh.

Additionally, during wartime, plebeians had to pay a military tax (tributum). They were not granted any share of public lands and could not graze their livestock on them. During military crises, their membership in the Roman army allowed them to pressure patricians to implement reforms. Wealthy plebeians who could afford cavalry equipment could achieve a form of equality with patricians within the ranks of the army.

Trade provided an avenue for plebeians to accumulate wealth, and some became wealthier than patricians. With the influence and power that money brought, they believed they deserved political rights and resented their lack thereof. They were subject to the authority of the consuls, who had extensive power over their lives with no right of appeal against their decisions. Plebeians were barred from holding public office and joining the aristocratic Senate. In assemblies, plebeians who were not clients (tenants or dependents) of patricians could be outvoted by those who were.

Additionally, plebeians were excluded from the administration of the state's religious institutions and major priesthoods. Dominated by a patrician-controlled legal system, plebeians often faced cruelty and injustice without knowledge of the laws or the ability to influence the legal system. They had no right of appeal against unjust decisions. Social mobility was further restricted by laws prohibiting marriage between plebeians and patricians, ensuring that any offspring from such unions remained plebeians.

Plebeian marriages typically took the form of coemptio (a fictitious purchase of the bride from her father) or usus (cohabitation). The fact that plebeians were excluded from political power by the patricians, who claimed descent from the first senators and so, led to the Conflict of the Orders. This centuries-long struggle for equal political rights resulted in significant legal reforms, including the creation of the Twelve Tables and other laws aimed at achieving greater political equality for plebeians.

The Conflict of the Orders

After the establishment of the Roman Republic, the plebeians continued to harbor resentment over their exclusion from political offices.

“Why fight in Rome's wars …when all the profits of their service lined patrician pockets? How could they count themselves full citizens when they were subject to random and arbitrary punishment, even enslavement if they fell into debt?”

Mary Beard, SPQR

According to the Roman historian Livy, after the founding of Rome, Romulus selected 100 men to establish the Roman Senate, which would govern the new city. These men were referred to as 'patres' (meaning 'fathers'), and their descendants formed the patrician class.

As Rome's ruling class, the patricians enjoyed various privileges, including exclusive rights to hold political and religious offices. Unlike the patricians, the origin of the plebeian class is not detailed by ancient authors. This omission is not surprising since, in ancient times, the history of common people was rarely recorded.

The plebeians were not part of Rome’s ruling elite but were members of the general citizenry. As powerless citizens, the plebeians sought to change their status, leading to the Conflict of the Orders, a struggle between the patrician and plebeian classes that lasted from 500 to 287 BC. The Conflict of the Orders arose from the plebeians' dissatisfaction with their political exclusion in Rome.

Political power was monopolized by the patrician class, and the situation worsened around the end of the 6th century BC. In 509 BC, with the deposition of Tarquinius Superbus, the last Roman king, and the establishment of the Roman Republic, the patricians gained more power. This included the seizure of public land, which had been royal property during the monarchy. The patricians increased their wealth by renting these lands or using slave labor, leaving the plebeians oppressed by hunger, poverty, and lack of power.

Land allotments did not solve the problems faced by poor farmers, whose small plots often became unproductive. Many plebeians whose lands were devastated by the Gauls couldn't afford to rebuild and were forced to borrow money. High-interest rates compounded their woes, as land couldn't be used as collateral, forcing them into contracts pledging personal service (nexa).

Those who defaulted (addicti) could be enslaved or killed. Recurrent grain shortages led to famines, exacerbating the plebeians' hardships, especially in the years 496, 492, 486, 477, 476, 456, and 453 BC. While some patricians profited and gained slaves from these miseries, Rome needed a robust fighting force to secure its growing power in Italy and the Mediterranean.

Similar to Greece, which had made concessions to lower classes for military support, Rome needed strong plebeian fighters. The plebeians responded to their problems—poverty, occasional famine, and lack of political influence—by establishing their own assemblies and seceding from the state. The physical necessity of plebeian soldiers for Rome's defense forced the patricians to concede to some plebeian demands, leading to gradual political reforms.

Luckily, the Conflict of the Orders was mainly bloodless and with an absence of violence.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: