Whispers Through Marble: The Enigmatic Acoustics of Herodes Atticus Odeon

Built for acoustic delight, The Odeon of Herodes Atticus still offers moments of unforgettable experiences for the audiences that flood its premises to enjoy various spectacles in Athens.

The Odeon of Herodes Atticus, is a jewel of Roman-Greek cultural fusion. It was commissioned by Herodes Atticus, a wealthy Athenian benefactor and Roman senator, as a tribute to his wife, Regilla, who tragically passed away under controversial circumstances. Herodes was known for his patronage of arts and education, and the Odeon became one of his most lasting legacies.

High-quality marble and cedar wood were primary construction materials. The seating, made of marble, played a role in sound absorption and reflection, ensuring even sound distribution across the auditorium. Unique window placements allowed natural light to flood the space without compromising its acoustic properties.

The marble preserved even today, able to host events till this day, shows the precision of Roman engineering. The stage’s elaborate decoration included colored marble and statues, reflecting the Odeon’s cultural significance as a space of artistic and musical excellence.

From Chorus to Concert: The Evolution and Acoustics of Ancient Odea

The odeon, also referred to as the odeum (plural: odea), originated as a Greek architectural structure designed specifically for musical performances and singing. Unlike the larger open-air theaters used for dramatic plays, the odeon was a roofed and columned hall, such as the Odeon of Pericles in Athens (built between 446–442 BCE).

The columns in these structures often obstructed sightlines. These smaller venues emerged alongside changes in dramatic styles, as later works by Greek playwrights like Sophocles and Euripides focused less on choruses and more on actor dialogues.

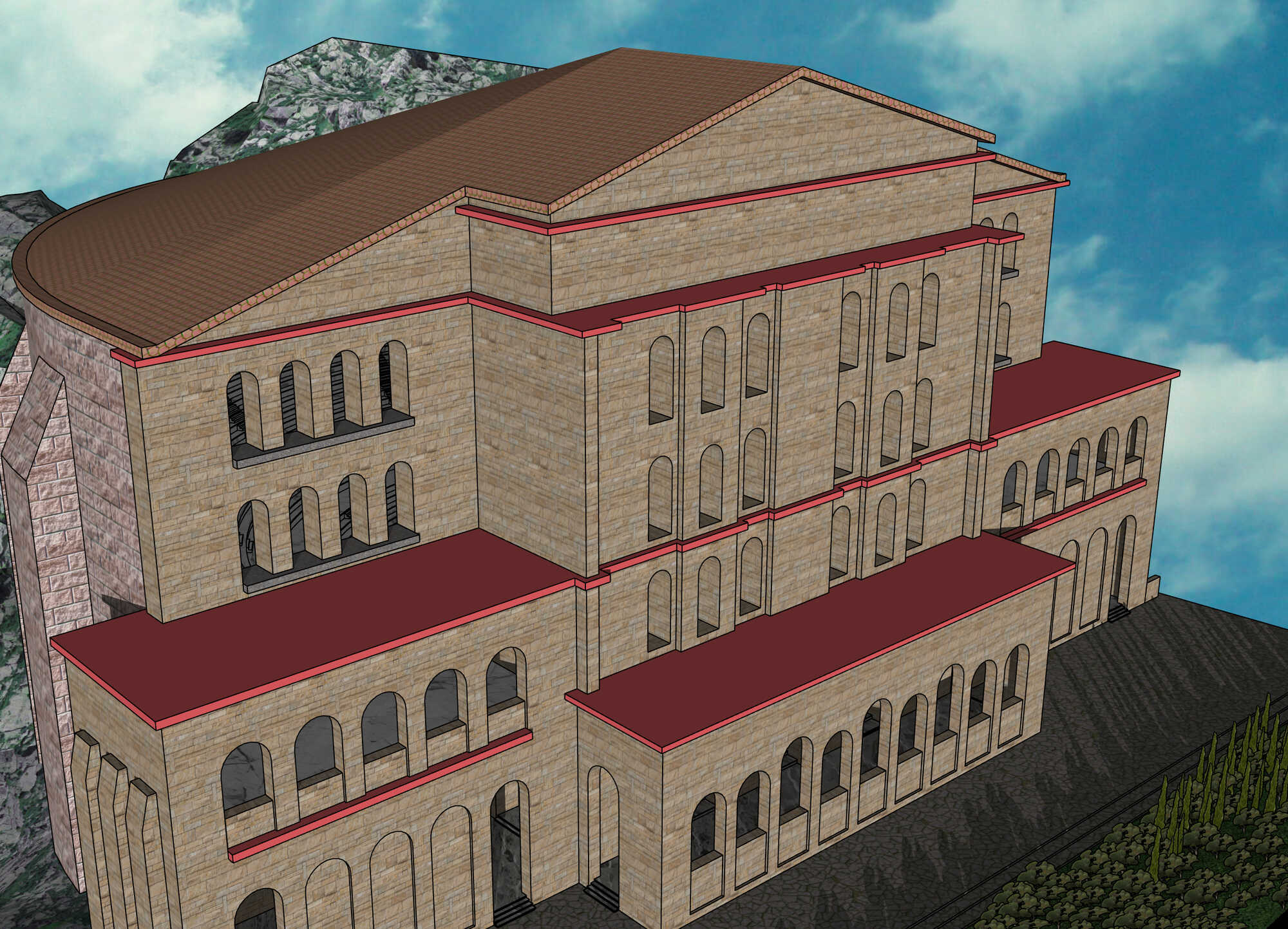

By the 1st century BCE, the Romans refined the odeon’s design, creating roofed theaters without internal columns and adopting a semi-circular audience arrangement similar to open-air theaters. A distinctive feature of these structures was their thick walls, built to support the timber roofs.

Their designs were either semi-circular or rectangular, with the semi-circular shape posing significant engineering challenges. Due to their wooden roofs, many odea have not survived intact, such as the Odeon of Agrippa in Athens (constructed in 12 BCE), which eventually collapsed in the mid-2nd century.

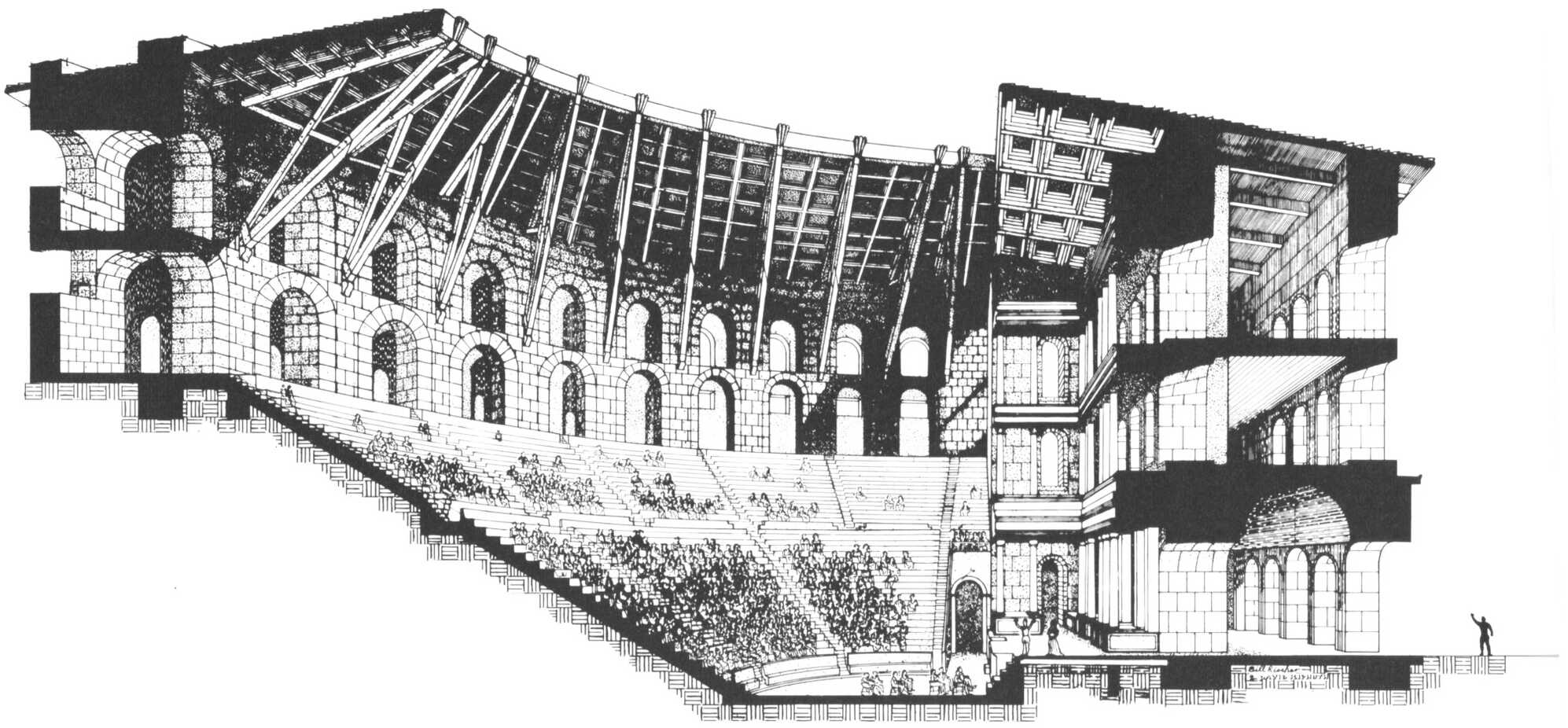

These structures, seating between 200 and 1,500 people, were prevalent in many ancient Greek cities. Roofed sections, often made from cedar wood, typically had a semi-circular shape and partially covered the marble seating (koilon). In some cases, elaborate roofs extended over the entire seating area and orchestra, with strategically placed windows allowing natural light to illuminate the stage. While the roofs may have been added for audience protection, it is also believed they enhanced acoustics for musical performances.

Today, these structures are preserved as open-air theaters, and their specialized function as venues for music is often misunderstood.

Simon Bolivar’s Youth Orchestra, performing a symphony at Odeon of Herodes Atticus in 2010. Credits: gichristof, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

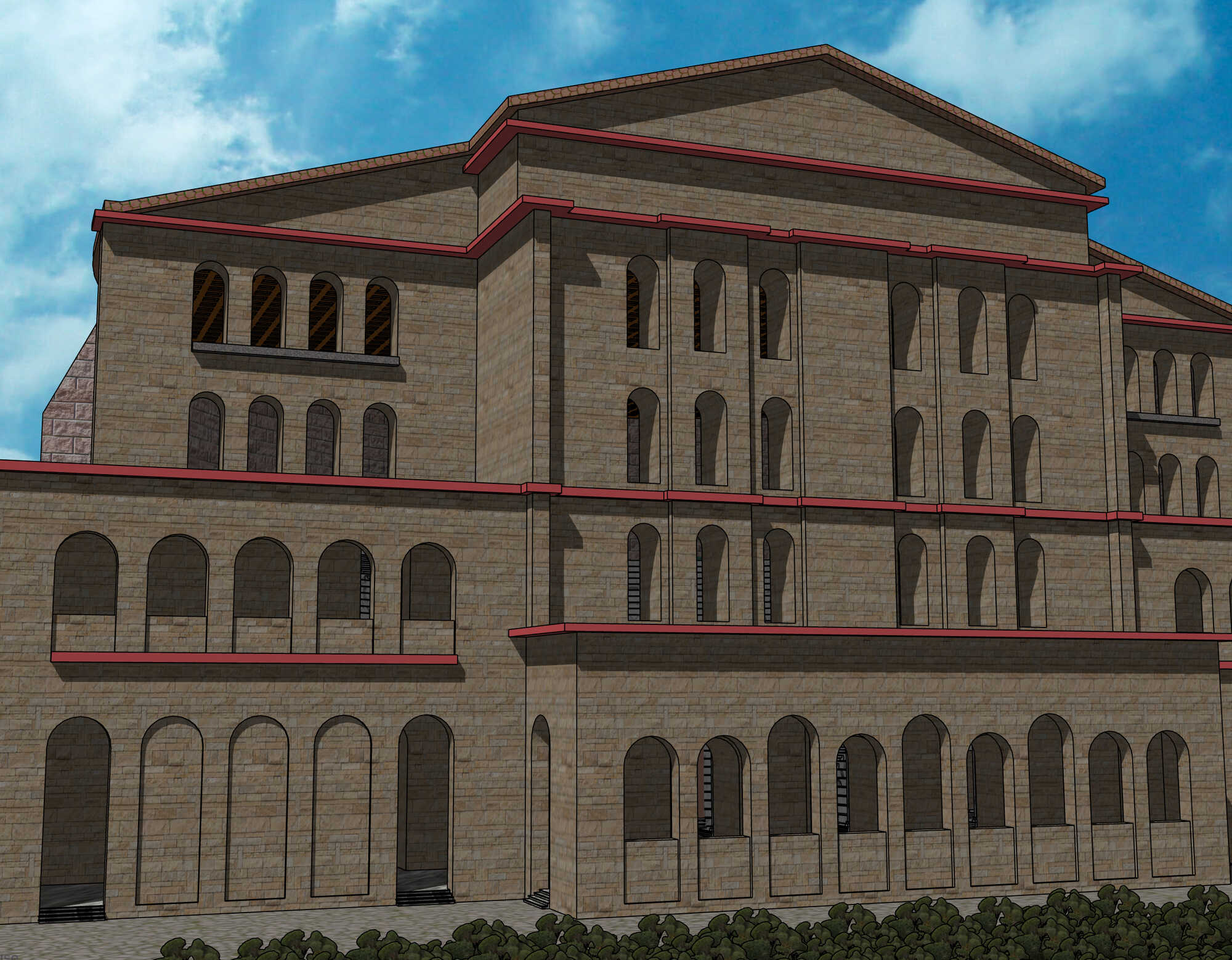

Modern acoustic studies, including measurements and simulations, have helped reconstruct the acoustic properties of roofed odea. For example, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, built in 161 CE on the southern slope of the Acropolis by Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes, was originally roofed but burned down in 267 CE.

Restored in the 1950s as an open-air venue, it now hosts music performances during the Athens Festival. With a capacity of nearly 5,000 spectators and constructed from marble, its current open-air acoustics are “dry,” characterized by a reverberation time of approximately 0.5 seconds and excellent speech intelligibility, even at the farthest seats.

Simulations of its original roofed version reveal an enclosed space with a volume of 9,750 m³ and a reverberation time of about 2.2 seconds. While this configuration supported the reproduction of musical instruments and vocal performances due to enhanced late reflections from the roof, speech intelligibility was notably poorer, especially for distant listeners. These acoustic differences highlight the roof’s role in tailoring the space for musical events.

Similar findings have been observed in other roofed theaters, such as the Odeon of Pompeii. Acoustic simulations of this partially or fully roofed Roman theater confirmed that its design was optimal for musical instruments and singing voices, further underscoring the distinct function of these structures as early specialized music venues. (Exploring the Acoustics of Ancient Open-Air Theatres, by Sara Giron, Ángel Ávarez-Corbacho, Teófilo Zamarreno. Instituto Universitario de Arquitectura y Ciencias de la Construcción (IUACC) Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura, Universidad de Sevilla)

The Evolution and Acoustics of Roofed Theaters in Ancient Greece and Rome

The name "Odeion," derived from the Greek word for song (ode), translates to “a place of song,” while the Latinized term "Odeum" served a similar purpose. In modern usage, the word has evolved to "Odeon," often referring to theaters, music halls, or even cinemas.

Unfortunately, the timber roofs of most Odeia were lost to fire or collapse over time, leaving these structures as open-air ruins. This transformation has contributed to a widespread misunderstanding of their purpose, with many mistakenly considering them simply as smaller, open-air theaters.

Yet, Odeia represent one of the earliest examples of theaters specifically designed for music performances before large audiences, making their acoustics particularly intriguing. Among these ancient Odeia, the Herodes Atticus Odeon in Athens stands out. Built in AD 161 by Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes, a wealthy teacher and philosopher, the structure was erected on the southern slope of the Acropolis.

The historian Pausanias described it as the “most significant building of its kind.”

Closeup of the main stage of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. Credits: Memitina from Getty Images Signature, by Canva

Originally roofed, it served as a vital cultural hub for musical and recital performances. Modern acoustic studies have sought to differentiate the original roofed acoustics from its current open-air form. The Herodeion, as it is affectionately known in Greece, offers a fascinating lens through which to explore these acoustic marvels.

Echoes of the Past: Acoustic Insights into the Roofed and Open-Air Versions of the Herodes Atticus Odeon

The Herodes Atticus Odeon offers a fascinating case for studying ancient acoustics due to its dual legacy as a roofed structure in antiquity and its current form as an open-air theater. Using advanced simulations alongside actual measurements from the open-air odeon, researchers confirmed that their models align closely with reality. This provides confidence in the accuracy of their results for the roofed version, assuming the archaeological data about its construction is correct.

The Odeon had steep marble seating (koilon) that could accommodate around 5,000 spectators. The seating extended slightly beyond a semi-circle and was divided into upper and lower sections by a central aisle. The stage house was originally a towering three-story structure adorned with statues and colored marble. The roof, made of timber, likely played a dual role: protecting the audience and enhancing the acoustics for music performances.

Today, the open-air version of the odeon behaves acoustically like larger Hellenistic theaters, with a relatively "dry" sound characterized by a short reverberation time of about 0.5 seconds and good speech intelligibility, even at the farthest listening positions — as already mentioned. Sound pressure decreases sharply over distance, typical of open-air spaces.

In contrast, the original roofed version would have created a much more resonant environment with a reverberation time of approximately 2.2 seconds. This enclosed space amplified musical instruments and vocal performances, providing richer, fuller sound. However, speech intelligibility would have been compromised, making the roofed odeon unsuitable for speeches or theatrical performances but ideal for music.

The timber roof transformed the acoustics, introducing late lateral reflections and enhancing the sound strength criterion, making it more akin to modern concert halls. These findings underscore the unique role of roofed odeia in antiquity as some of the earliest purpose-built venues for music performances.

Although it is unclear whether ancient builders intentionally designed the roof to optimize acoustics, the Herodes Atticus Odeon stands as a testament to the ingenuity of ancient Greek and Roman architectural practices. Further interdisciplinary research may illuminate how much the ancients understood about acoustics and their influence on later concert hall design. (The Acoustics of Roofed Ancient Odeia: The Case of Herodes Atticus Odeion, by Stamatis L. Vassilantonopoulos, John N. Mourjopoulos. Audio and Acoustic Technology Group, Wire Communications Laboratory, Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, University of Patras)

Exploring the Acoustic Marvels of Herodes Atticus Odeon

In “Project Ancient Acoustics Part 2 of 4: large-scale acoustical measurements in the Odeon of Herodes Atticus and the theatres of Epidaurus and Argos,” Niels Hoekstra, Bareld Nicolai, Bas Peeters, Constant Hak and Remy Wenmaekers for the 23rd Internation Congress on Sound & Vibration, presented some amazing findings.

The study delves into the unique acoustic properties of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus in Athens, providing insights into how this ancient theater was designed and how it functioned in both its original roofed form and its current open-air state. Using advanced acoustic measurement techniques and simulations, the researchers explored how the Odeon was optimized for music and performance.

The Odeon of Herodes Atticus, was originally covered with a wooden roof, (as aforementioned) a rare feature that distinguished it from other ancient theaters. The timber roof served dual purposes:

- Protection: Shielding the audience from the elements.

- Acoustics: Enhancing sound resonance, particularly for musical performances.

Today, the Odeon functions as an open-air theater, and its acoustics reflect this transformation:

- Reverberation Time (T20): Around 1.5 seconds. This moderately "dry" acoustics is suitable for speech clarity and allows for balanced sound projection.

- Sound Strength (G): The sound level decreases predictably with distance, maintaining good clarity throughout the seating area.

- Speech Intelligibility (STI): Modern performances, typically amplified, maintain excellent speech clarity for audiences.

- The steeply angled seating ensures that even distant spectators can hear sounds clearly. However, without its roof, the Odeon’s acoustic performance for music is less rich than it would have been in antiquity.

Acoustic Simulation of the Roofed Odeon

The researchers reconstructed the theater's original roofed form using simulation software, based on historical and archaeological records. The results revealed fascinating differences between its ancient and modern states:

- Reverberation Time: In its roofed version, the theater's reverberation time extended to 2.2 seconds, ideal for musical performances. The roof amplified reflections, creating a warm and resonant sound environment.

- Sound Propagation: The wooden roof and surrounding walls created an enclosed acoustic environment. Sound traveled further with less loss of energy, making music and vocal performances immersive.

- Speech Intelligibility: The roofed version struggled with speech clarity, particularly for distant listeners. Speech intelligibility was about 20% worse than in the open-air version, suggesting it was not primarily designed for spoken drama or oratory.

The study highlights the advanced understanding of acoustics by ancient architects:

- Purpose-Driven Design: The roof and semi-circular seating were optimized for music and singing rather than theatrical performances.

- Multipath Reflections: The timber roof created secondary sound reflections that added richness to music but made spoken words less distinct.

- Architectural Ingenuity: The Odeon’s designers appeared to balance aesthetics, functionality, and acoustics, anticipating the needs of musical performances for large audiences.

Recreating Ancient Sounds: Virtual Acoustics and the Odeon

Another study provides additional details emphasizing the integration of advanced technology to explore the acoustics of the Odeon. A detailed 3D model of the roofed and occupied Odeon was created to simulate its acoustics for Virtual Reality Applications.

This model was integrated into a virtual reality (VR) environment, enabling users to experience the theater acoustics interactively. Virtual navigation allowed users to "hear" how performances might have sounded in antiquity. Advanced Acoustic Modeling was used, in which the acoustic simulations accounted for environmental factors like temperature and humidity, and the materials' properties were modeled with precise absorption and scattering coefficients.

Specific attention was paid to the seating area geometry, which influenced sound reflections:

- Audience Impact on Acoustics: Simulations revealed significant differences in acoustics when the theater was empty versus 85% occupied. The audience's presence reduced reverberation times and improved clarity, particularly for music.

- Key Findings for Speech and Music: Speech intelligibility was classified as "poor" in the empty theater but improved to "fair" with an audience. This confirmed that the Odeon was more suited to musical performances than speech-centric events.

Enhanced clarity and sound strength were observed in central positions, making these areas optimal for audience experiences during performances. The VR reconstruction not only enhances understanding of the ancient theater's design but also serves educational and tourism purposes, providing an immersive glimpse into the past. (An investigation into the acoustics of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, by Eleni Tavelidou MSc, Solent University Chris Barlow Prof, PhD, MIOA, MAES, Solent University)

The Odeion and the surroundings are an experience if you are in Greece, so when in Athens, do make sure to book your tickets for a concert in the Herodeion. Approaching the Odeon of Herodes Atticus you will be awed by the site of the sacred rock of Acropolis. Arrive early to enjoy the sun kissing the marbles as it sets. Watch the people arriving and slowly flooding the site. All performances are full; always! And after the performance ends, walk on Dionysiou Areiopagitou street under Acropolis and go straight, until you meet Hadrian's gate.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: