What Romans Used More Than Stone

Stone built Rome’s image, but leather sustained its daily life. From tanneries and shoemakers to soldiers on the frontier, this invisible material economy supported movement, labor, and power across the Empire.

Rome is remembered in stone. Temples, amphitheaters, roads, and arches dominate both the ancient landscape and the modern imagination. Marble survives; bronze leaves traces; inscriptions endure. Yet the Roman world did not function on stone alone. Beneath the monuments lay a far more perishable infrastructure—one that rarely survives archaeologically, yet was indispensable to soldiers, farmers, craftsmen, traders, and officials alike. Without it, armies could not march, goods could not travel, tools could not work, and bodies could not be protected. What sustained the empire day by day was not what was meant to last forever, but what was used until it wore out.

Leather as an Urban Necessity

Leather was one of the most indispensable materials of Roman daily life. Long before stone, marble, or bronze entered a household, leather was already present—shaping footwear, clothing, military equipment, transport, storage, and trade. Its importance lay not in monumentality but in constant use. Every Roman city depended on a steady supply of hides transformed into durable goods that could withstand friction, moisture, and strain.

Urban economies therefore required organized systems for acquiring raw hides, processing them, and distributing finished leather products. These processes were neither marginal nor occasional. They formed a permanent layer of urban production, closely tied to food supply, animal husbandry, and market exchange. Leatherworking was not a luxury craft but a foundational one, supporting movement, labor, and administration across the Empire.

From Slaughterhouse to Workshop

The leather industry began with animals raised primarily for meat, transport, or labor. Hides entered the production chain as by-products of slaughter, meaning that tanning was structurally linked to butchery and food markets. In cities, hides were collected locally from slaughterhouses or imported from surrounding rural areas, particularly in regions with strong pastoral economies.

Once removed, hides required immediate treatment to prevent decay. This urgency shaped the spatial organization of tanning workshops. Leather processing was time-sensitive, water-intensive, and produced strong odors, which influenced where it could be carried out within the urban fabric.

The Coriarii: Tanners and Their Craft

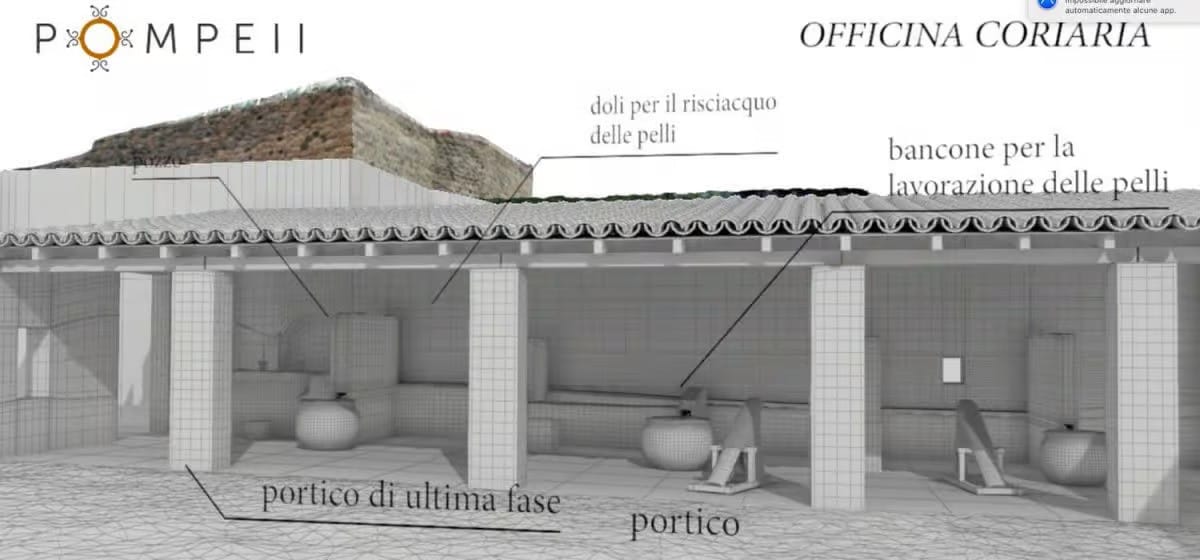

Tanners (coriarii) occupied a clearly defined but socially ambiguous position in Roman society. Their work was essential, but it was also regarded as unpleasant. Tanning involved soaking hides in water, removing hair and flesh, and treating the skins with organic substances such as urine, dung, or plant-based tannins. These processes produced waste, smells, and runoff that made tanning incompatible with elite residential areas.

As a result, tanneries were typically located on the edges of cities, near rivers, streams, or drainage channels. This pattern appears repeatedly in archaeological and textual evidence. Tanneries required constant access to water, both for soaking hides and for flushing away waste, making proximity to natural water sources a practical necessity rather than a choice.

Despite their marginal placement, tanneries were not informal or temporary. They were fixed installations, often consisting of vats, basins, and work areas that required investment and permanence. Their presence reflects long-term planning rather than ad hoc production.

Because of its environmental impact, tanning was subject to regulation. Roman cities frequently imposed restrictions on noxious crafts, either through zoning practices or customary expectations. While explicit legal texts on tanners are limited, the consistent archaeological pattern suggests widely shared norms about separating polluting industries from civic and domestic spaces.

This separation did not imply exclusion from the economy. On the contrary, leatherworkers were integrated into urban commercial networks. Their workshops were connected to markets through supply chains that brought hides in and finished goods out. Regulation shaped location, not legitimacy.

Shoemakers and Secondary Crafts

Once tanned, leather entered a second phase of production involving skilled artisans such as shoemakers (sutores), harness-makers, and other specialists. These crafts were less polluting and could operate closer to commercial centers and residential districts.

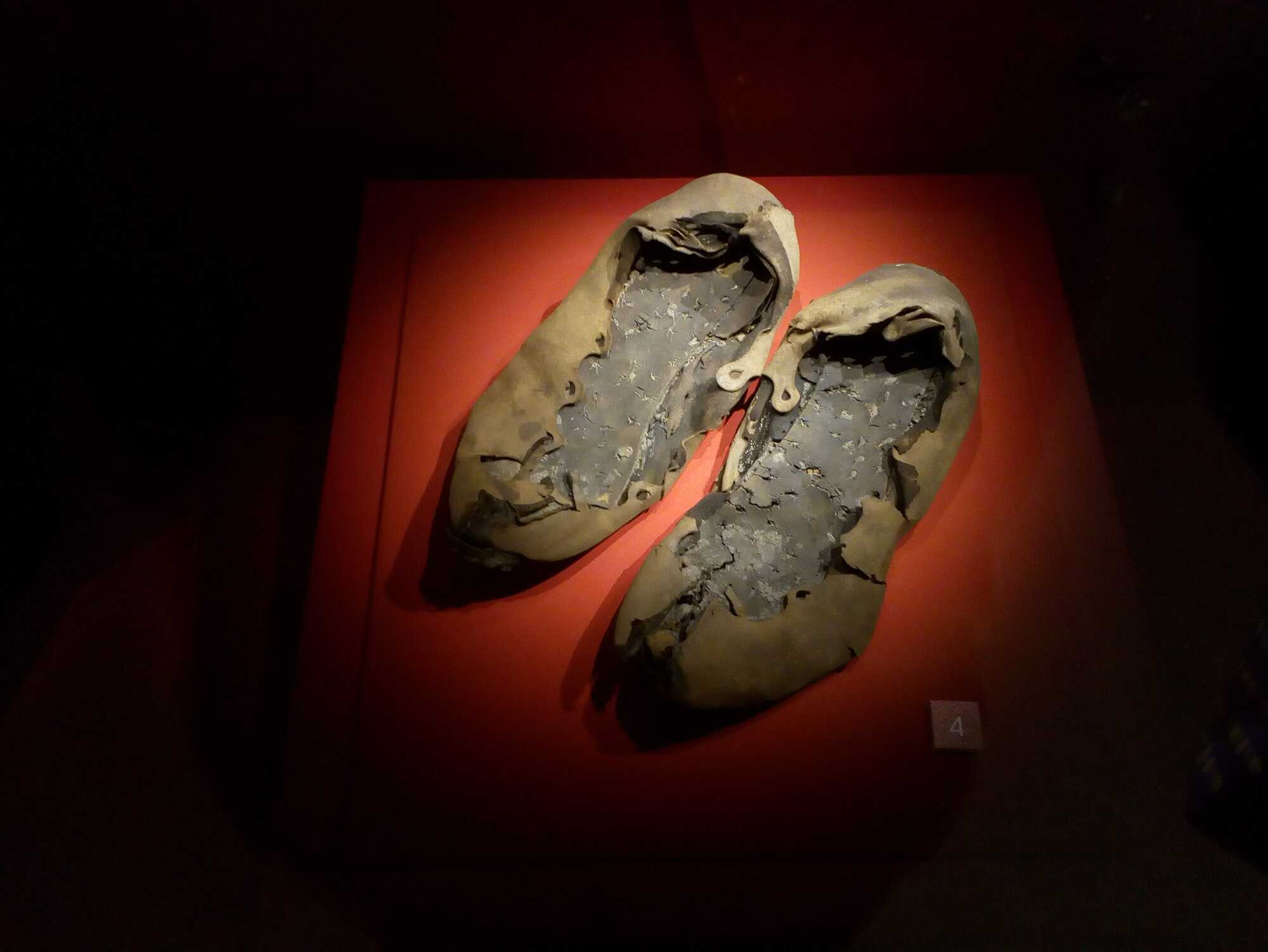

Shoemaking in particular was ubiquitous. Footwear was essential for soldiers, laborers, travelers, and urban populations alike. Roman shoes varied by function, status, and environment, but all required reliable leather supply. Shoemakers often worked in small workshops, sometimes combined with retail spaces, producing and repairing footwear for local customers.

Repair was as important as production. Leather goods were valuable and frequently mended, reshaped, or reused. This culture of maintenance extended the lifespan of leather products and reduced waste, reinforcing the material’s economic importance.

Small Workshops, Empire-Wide Demand

Leatherworking in Roman cities was primarily small-scale and workshop-based. There is little evidence for large centralized factories comparable to modern industrial production. Instead, tanning and leatherworking were carried out by numerous independent or family-run enterprises.

This decentralized structure allowed flexibility. Production could respond to local demand, seasonal availability of hides, and fluctuations in population. It also meant that leatherworking was resilient: the loss of one workshop did not disrupt supply across the city.

At the same time, the cumulative output of these workshops was substantial. When multiplied across hundreds of cities and towns, leather production formed a massive but largely invisible sector of the Roman economy.

Necessary Work, Modest Status

Leatherworkers occupied a modest social position. Like other manual craftsmen, they were rarely celebrated in elite literature, and their work carried none of the prestige associated with fine arts or monumental building. Tanners in particular were sometimes viewed with distaste due to the nature of their labor.

Yet this social marginality should not be confused with economic insignificance. Leatherworkers earned steady incomes, participated in urban trade, and were embedded in local communities. Some belonged to professional associations (collegia), which provided social support, religious participation, and collective identity.

Inscriptions and archaeological traces suggest continuity rather than precarity. Leatherworking was a stable occupation, passed down through generations, sustained by constant demand.

Leather everywhere, for all seasons and all types of weather

Beyond clothing and footwear, leather played a crucial role in transport and administration. Leather straps, harnesses, saddles, and coverings supported animal traction and long-distance movement of goods. Bags, pouches, and containers made of leather were used for storage and transport, especially where flexibility and durability were required.

Administrative and military contexts relied heavily on leather. Writing tablets, scroll covers, and equipment cases depended on treated hides. While such items rarely survive archaeologically, their widespread mention in texts indicates routine use.

The pervasiveness of leather meant that its absence from the archaeological record is misleading. Unlike stone or ceramics, leather decays quickly unless preserved under exceptional conditions. What survives represents only a fraction of what once existed.

Pompeii and its leather market

Pompeii provides unusually clear evidence for the organization of leatherworking within a Roman city. Archaeological remains indicate the presence of both tanneries and shoemaking workshops, confirming the spatial separation between primary processing and secondary manufacture.

Tanneries at Pompeii were located near water sources and away from elite housing, consistent with patterns observed elsewhere. Shoemakers operated closer to commercial zones, reflecting their role in retail and repair. Together, these workshops demonstrate how leather production was integrated into urban life without dominating it.

Pompeii’s evidence confirms that leatherworking was not peripheral or rural but fully urban, adapted to city planning and economic rhythms.

An Invisible Material Economy

Leather rarely survives, and leatherworkers rarely speak in surviving texts. Yet the material was everywhere. It shaped how Romans walked, worked, fought, traded, and traveled. Cities functioned because leather absorbed stress, movement, and wear that stone and metal could not.

Understanding Roman leather production therefore requires shifting attention away from what survives toward what was used. The industry’s scale, organization, and urban integration reveal a material economy that underpinned daily life across the Empire. (“Urban craftsmen and traders in the Roman world” edited by Andrew Wilson & Miko Flohr)

If urban archaeology and literary sources allow us to reconstruct how leather was produced and distributed, they tell us far less about how leather objects were actually used, worn, and discarded. For that, an exceptional body of evidence is required—one where leather survived not by design, but by circumstance.

Such evidence exists at Vindolanda.

The Roman occupation of north-western Europe brought with it changes that reached far beyond politics or administration. At a basic technological level, it disrupted long-established local practices and reshaped everyday experience in ways that are only now being fully appreciated. Among the most significant—and archaeologically visible—of these changes were new methods of working animal skins and new approaches to making footwear.

Leather and Life Along Hadrian’s Wall

Before the Roman conquest, communities in north-western Europe did not generally use vegetable tanning. Instead, skins were preserved through techniques such as the application of oils and fats or by smoking. These methods continued to be employed in regions that lay beyond Roman control.

None of them, however, produced leather that was permanently stable or resistant to moisture. As a result, objects made from treated skins could survive only in exceptional environments, such as extremely dry conditions, highly saline contexts, or peat bogs, where natural chemical processes could incidentally preserve organic material.

Vegetable tanning marked a decisive break from these earlier practices. By treating hides with plant-based extracts, it produced leather that was chemically durable and far more resistant to decay, particularly in damp, oxygen-poor environments.

This technology was already known in the Mediterranean world by at least the fourth century BCE, although its origins and routes of transmission remain uncertain. Its introduction into north-western Europe had immediate archaeological consequences: from the beginning of Roman occupation, leather goods suddenly become far more visible in the material record.

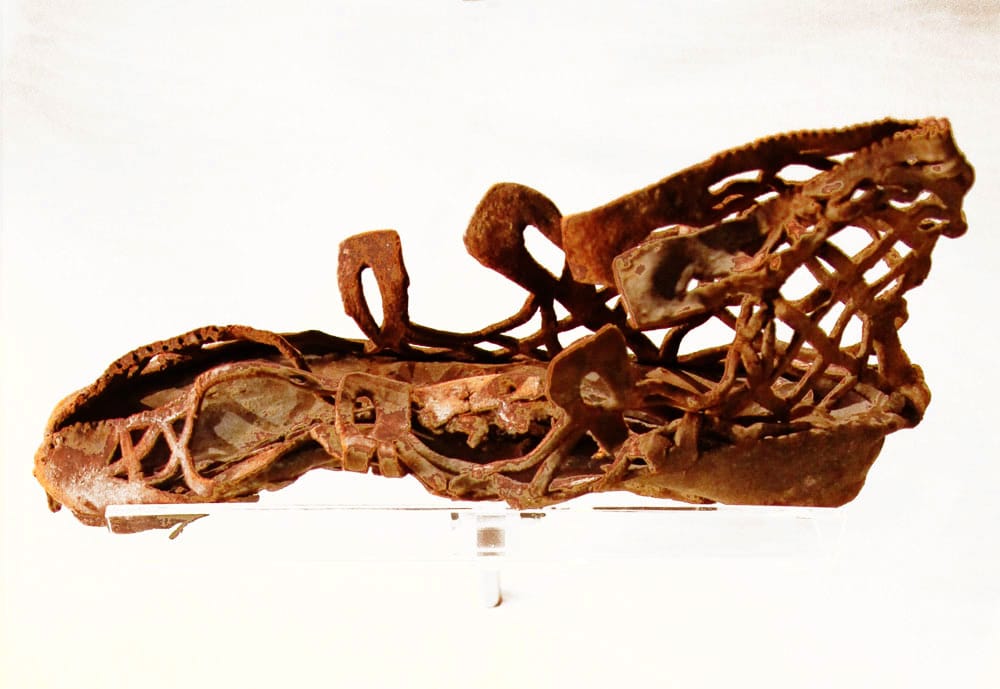

Footwear production underwent a similar transformation. Roman shoes introduced forms and construction techniques that had no clear antecedents in local traditions. Hobnailed shoes and sandals were entirely new, but even footwear types that appear superficially similar to earlier native forms—such as single-piece shoes—were based on different design principles and concepts of use.

The appearance of leatherworking on a large scale in waterlogged archaeological contexts therefore reflects not the continuation of older customs using new materials, but the arrival of an integrated technological system encompassing both tanning and manufacture. Especially in the first generations after conquest, these changes likely carried strong cultural and political meaning.

Roman shoemaking also differed fundamentally from both prehistoric and later medieval practices in its technical diversity. Shoemakers produced a wide range of shoe types, some of which appear to have been designed for specific activities or contexts. Evidence from a grain ship that sank in the Rhine around 210 CE, where each crew member possessed both closed shoes and sandals, suggests an awareness of functional differentiation in footwear.

This implies a shift in attitudes toward clothing: shoes were no longer merely practical items but part of a broader system of social signalling, drawing on shared conventions that were widely understood across Roman society.

The spread of vegetable tanning and Roman footwear technology is closely associated with the army. Both appear first in military contexts, not only in Europe but also in provinces such as Egypt. Throughout the Roman period, military installations remain among the richest sources of leather finds, followed closely by urban settlements.

In many cases, however, the contexts that preserve leather—riverside refuse layers, ditches, and wells—are difficult to date precisely, making it hard to trace developments over time within organic assemblages.

Some military sites provide clearer sequences. At Valkenburg in the Netherlands, for example, early phases dating to around 40–50 CE were sealed during later restructuring, preserving leather from the site’s initial occupation, while later phases yielded far fewer organic remains.

Vindolanda, by contrast, presents an exceptional case. There, a combination of local topography and repeated rebuilding episodes led to the preservation of unusually large quantities of leather artefacts. These finds are not only abundant but also stratified within a relatively well-dated sequence that spans the entire Roman occupation of the site.

A Frontier Archive in Leather

Excavations carried out between 1985 and 1988 at Vindolanda produced an exceptional volume of leather material. More than 2,600 individual find numbers were assigned to leather recovered.

Among the finds, footwear dominates the assemblage. Of the 1,447 items that could be securely identified as shoes or shoe components, most consist of soles, though Vindolanda is notable for the unusually high survival rate of upper leather. This appears to reflect the frequent use of cowhide, which is thicker and more resilient than the skins commonly employed elsewhere.

On technological grounds, the footwear can be divided into six principal types: single-piece shoes (carbatinae), nailed shoes, sewn shoes, sandals, slippers, and wooden clogs. While the majority of surviving uppers are associated with nailed soles, sewn constructions are also well represented.

The original appearance of each shoe is primarily determined by the form of its upper. These uppers can be classified into distinct stylistic groups based on visual characteristics, most notably fastening systems, but also cutting patterns and the height of the shoe in relation to the ankle. Using these criteria, thirteen recurring styles can be identified, each represented by at least four examples within the assemblage.

From the later second century onward, however, the material shows a marked diversification, with a growing number of styles represented by only one or two surviving examples.

One of the most striking characteristics of Roman nailed footwear is the extent to which it transcends regional boundaries. Styles not only evolve quickly, but they do so in a broadly synchronized manner across the north-western provinces of the Empire and, where the archaeological record permits comparison, across Mediterranean regions as well. In this sense, it is not inappropriate to speak of something akin to “fashion”: a continuous and relatively rapid turnover of forms shared across wide geographical areas.

This international consistency gives the Vindolanda sequence a value that extends far beyond the site itself. Because the stylistic changes appear to be contemporaneous across provinces, the chronological framework established at Vindolanda can be transferred to other archaeological contexts.

At its most basic level, Roman footwear can therefore function as an independent dating tool. An otherwise undated assemblage from Old Penrith, for example, can be assigned to a style group, recognizable by its horizontal lacing that produces a raised ridge along the length of the foot.

Comparison with the Vindolanda seriation places this style in the late second or early third century, allowing the associated material to be dated accordingly.

The Vindolanda sequence also proves valuable in addressing assemblages recovered from riverside refuse deposits, where stratigraphy is often complex and mixed material has obscured chronological development. Footwear from the vicus at Valkenburg in the Netherlands illustrates this point.

Although largely undated, the assemblage includes a small number of styles characteristic of the mid-second century, followed by a concentration of types associated with the transition from the later second to the early third century.

A limited number of examples appear to post-date this phase, and some sandals may even extend into the middle of the third century. Comparable patterns are visible in the unpublished footwear assemblage from the fort at Vechten, suggesting that activity in the civilian settlements surrounding these forts continued well into the third century.

Sandals represent the most visibly Mediterranean element introduced into footwear traditions of the northern provinces. Although their soles were fastened with leather thongs, they were typically reinforced with hobnails, leaving little doubt that they were intended for outdoor use rather than domestic wear.

In the earliest military contexts, sandals occur only rarely. At Vindolanda, they are found mainly in small sizes, a pattern that strongly suggests an association with women and children and, by extension, the presence of military families rather than soldiers alone.

In contrast, early civilian settlements show a much higher proportion of sandals. At Billingsgate in London, for example, they account for nearly a quarter of all recorded footwear, although once again smaller sizes dominate. This pattern points to civilian adoption rather than military issue as the main driver behind their early spread in the north.

Unlike closed shoes, which undergo abrupt stylistic transformations, Roman sandals evolve gradually and consistently over a span of roughly four centuries. Their development follows a clear and continuous trajectory that appears remarkably uniform across provincial boundaries.

Sandal soles generally retain a natural foot shape, often marked by two or three indentations corresponding to the toes. In some cases, particular emphasis is placed on the second toe—a feature that reflects long-standing Classical aesthetic preferences visible in Hellenistic sculpture and later artistic traditions. This suggests that the introduction of sandals carried with it not only a new form of footwear, but also inherited ideals about the body and its presentation.

The gendered dimensions of this adoption are especially striking. Evidence from shoe sizes indicates that women were among the first in civilian communities such as London and Cologne to adopt the full range of Roman footwear styles. At Vindolanda, however, this pattern is complicated by the presence of two sandals from a specific period’s barrack block that are adult male in size.

One of these bears a stamped eagle motif, identical to a stamp found on a sandal from London. This suggests that the uptake of sandals may also have carried connotations of status or official affiliation, rather than being determined by gender alone.

Decorative stamping becomes increasingly common on sandal soles during this period. Simple motifs such as urns, concentric circles, and floral designs predominate, but more elaborate patterns—apparently impressed using metal dies—also appear. The sandals recovered from a specific period’s deposits at Vindolanda illustrate a moment of stylistic transition between earlier and later forms.

They include a small number of earlier forms alongside a larger group that resembles the more developed styles found in another period’s (based on the excavator’s original stratigraphic dating) ditch, likely reflecting activity shortly before the ditch was cut. Post-depositional factors may also have influenced preservation, as the upper levels of the ditch fill show signs of repeated drying.

Later sandal types are well attested at Birdoswald and numerous other sites in Britain and across the Continent. In Egypt, similar shapes were even reproduced using vegetable fibre, underlining the broad diffusion of the style. These later sandals are characterized by notably wide soles, which would have altered the wearer’s posture and movement, producing a distinctive, striding gait with the shoulders held back. This bodily effect has previously been linked to the wider militarization of Roman society.

Alongside these bold forms, more restrained sandal types also emerge in the late third and early fourth centuries. These are often smaller in size and feature a deep, scroll-like indentation along the side, suggesting continued variation in gendered or social usage. Taken together, the sandal assemblage from Vindolanda indicates that most of the leather from the late ditch dates to the mid-third century, although footwear from the fourth century—particularly sewn shoes and carbatinae—is also present in significant numbers. ("Vindolanda and the Dating of Roman Footwear" by Carol van Driel-Murray)

Stone may define how Rome is remembered, but leather defined how it functioned. It carried the weight of soldiers, absorbed the strain of labor, moved goods across roads and rivers, and shaped bodies in motion. Its disappearance from most archaeological contexts has obscured its importance, not diminished it. Where conditions allow it to survive, as at Vindolanda, leather reveals an empire sustained not only by monuments and law, but by a material economy of wear, repair, and constant use—one that made Roman power livable, mobile, and real.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: