Saturnalia: The Roman Festival that Inspired the Spirit of Christmas

Was Saturnalia of the ancient Romans what Christmas is for us today? The two have a lot in common. How was Saturnalia celebrated?

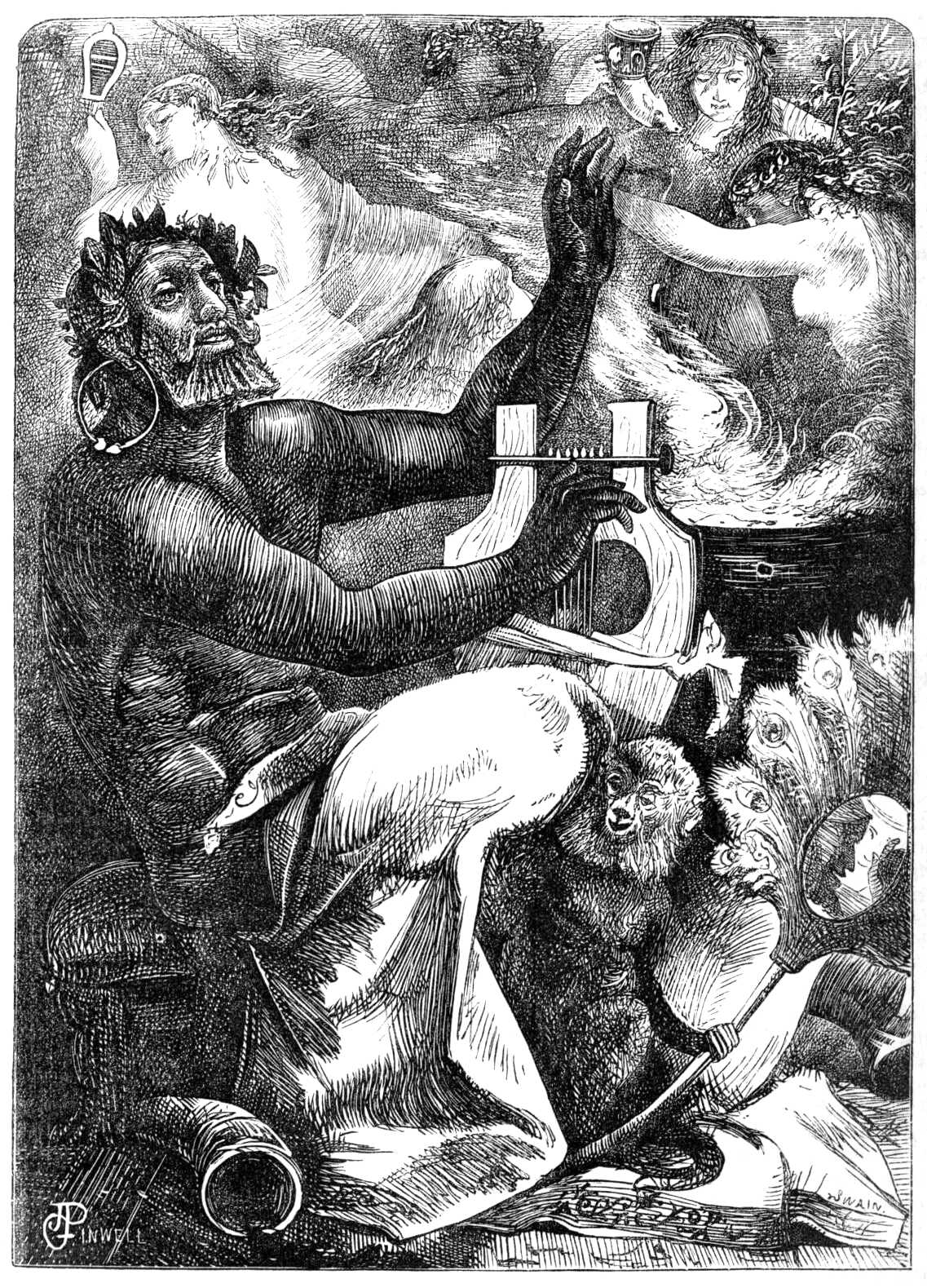

In the heart of December, as the chill of winter settled over the Roman world, an extraordinary festival turned societal norms on their head. Saturnalia, a week-long celebration dedicated to Saturn, the god of sowing and agriculture, transformed the rigid structures of Roman life into a whirlwind of laughter, generosity, and revelry. Slaves dined as equals with their masters, dice games determined who would reign as “king” of the festivities, and the city streets echoed with cries of “Io Saturnalia!”

But Saturnalia wasn’t merely a time of chaos—it was a celebration of abundance, renewal, and shared humanity. Could this exuberant ancient festival have sown the seeds for the way we celebrate Christmas today?

Io Saturnalia! The Feast of Saturn and the Origins of Holiday Traditions

Saturnalia was one of the oldest Roman festivals, held in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture, fertility, and rebirth. According to Frazer, (a Scottish social anthropologist, folklorist, and classical scholar) Saturn was remembered as a just and benevolent king who united scattered mountain dwellers, taught them to farm, established laws, and ruled in peace.

Saturn’s reign, often referred to as the Golden Age, symbolized a utopia where there were no slaves, no private property, and no social hierarchies. It was an era of abundance and liberty, where everyone lived in harmony and shared equally in prosperity. The Roman historian Justinus attributes this idealized age to Saturn’s governance, stating:

“The first inhabitants of Italy were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all.”

To honor Saturn’s legacy, the festival recreated this vision of equality, allowing slaves to dine with their masters and upending societal norms, even if only temporarily. Saturn thus became a symbol of abundance, freedom, and equality, reflected in the weeklong festivities marked by feasting, gambling, gift-giving, and drinking.

Saturnalia originally started as an agricultural celebration, coinciding with the winter solstice, when the year’s final harvest was gathered. The festivities began on December 17 and typically lasted until December 23, although at times it extended to December 25.

This close timing with the solstice contributed to Saturnalia’s transformation into Christmas during the Christianization of Rome.

Stonehenge during the Winter Solstice. Credits: TimothyBall from Getty Images Signature, by Canva

The festival’s central themes included overturning social norms, extravagant feasting, generosity toward the poor, and lighting the streets with large candles known as sigillaria. The city was decorated lavishly, and the phrase “Io Saturnalia!” echoed through the streets, uniting people from all walks of life in joyous celebration.

Frazer described the atmosphere of the celebrations as one of uninhibited merriment and freedom, noting:

“The customary restraints of law and morality are thrown aside, when the whole population give themselves up to extravagant mirth and jollity, and when the darker passions find a vent which would never be allowed them in the more staid and sober course of ordinary life.”

On the festival’s first day, Roman citizens and farmers from nearby regions traveled to the Temple of Saturn, located at the foot of Capitoline Hill, creating a massive swell in the city’s population. The temple visit resembled a pilgrimage, with people gathering to pay tribute to Saturn. Bulls were paraded through the streets, accompanied by Roman senators and priests, before being sacrificed at the temple.

At the temple, Saturn’s statue—bound in wool and filled with olive oil—symbolized his temporary release from captivity. Priests initiated the festival by unbinding the statue’s woolen fetters and placing it at the head of a grand banquet. This act symbolized Saturn reclaiming his throne, previously abandoned to Jupiter/Zeus, and ruling over Rome for the duration of the celebrations.

For the next few days, the sigillaria, and the cries of “Io Saturnalia!” allowed people to be indulged in a brief, utopian glimpse of the Golden Age.

A possible representation of the festivities happening during the Roman Saturnalia. Illustration: Midjourney

Freedom and Equality for a Day: The Saturnalia’s Echoes of the Golden Age

Some scholars draw comparisons between Saturnalia and other festivals that temporarily reversed societal roles between masters and slaves. Roman festivals like Saturnalia (starting December 17), the Compitalia (an agrarian thanksgiving), and the Nonae Caprotinae (celebrated by free women and female slaves on July 7) allowed for these role reversals.

Similarly, the Matronalia on March 1 involved mistresses possibly serving meals to their female slaves, though the evidence for this is late and comes primarily from the fifth-century writer Macrobius:

“In March... matrons would wait on their slaves at dinner, just as the masters of the household did at the Saturnalia.”

Other authors mention Matronalia as an anniversary of the Temple of Juno Lucina or a time when matrons received gifts, but do not confirm Macrobius’s account.

The Nonae Caprotinae also involved acts of solidarity between free women and slaves. According to Plutarch and Macrobius, the festival commemorates an incident where female slaves disguised themselves as their mistresses to save Rome’s free women from being handed over to the Latins. The celebrations included sacrifices at a fig tree, mock battles, and dramatic begging processions.

Saturnalia is better documented, though questions remain about its precise nature. During this festival, Saturn (Cronos), whose temple stood at the base of the Capitol in Rome, was symbolically freed from his chains.

For several days, depending on the period, the god "ruled" in place of Jupiter. Public festivities included offerings, banquets (lectisternia), and private celebrations involved feasting, drinking, and general merriment, with slaves enjoying time off. Even Cato the Elder, in his agricultural guide, recommended giving each slave a gallon of wine during Saturnalia and the Compitalia.

Roman male citizens wore short tunics instead of togas and donned the pileus (a cap symbolizing freedom or manumission). Gambling and dice games, normally forbidden, became a central amusement. Patrons hosted clients, and dinners were filled with wit, satire, and entertainment.

The festivities were visually captured in the Calendar of Filocalus (354 CE), which included symbolic representations like dice, masks, and birds associated with Saturnalian games and gifts. Another mosaic from El-Djem in Tunisia shows slaves carrying torches and wax candles, reflecting their role in the celebrations.

The role reversals during Saturnalia were often noted in ancient sources. Early Roman poet Accius wrote:

"In most of Greece, and above all at Athens, men celebrate in honor of Saturn a festival... at which each man waits on his own slaves.

Athenaeus similarly observed, "During the Saturnalia... it is customary for the Roman children to entertain the slaves at dinner."

The philosopher Seneca also reflected on the theme, discussing how Roman traditions aimed to mitigate the master-slave divide by dining together during Saturnalia. He wrote:

“They called the master 'father of the household' and the slaves 'members of the household…'

They established a holiday on which masters and slaves should eat together.”

Seneca, however, saw this as an opportunity for moral education, advocating that masters should treat slaves based on their character rather than their duties.

Literature from the period, including comedy and satire, often referenced Saturnalia’s role reversals.

A sculpture depicting Saturnalia, by Ernesto Biondi. Public domain

Cassius Dio described how, during a military campaign, Roman soldiers mockingly shouted "Io Saturnalia" at a slave attempting to quell unrest. In Horace’s satire, a slave named Davus used "the license December allows" to criticize his master, reinforcing the idea of Saturnalia as a temporary and controlled inversion of social norms.

While most slaves likely experienced Saturnalia as a brief respite with better food and wine, it also offered an opportunity for larger gatherings, open speech, and satirical commentary. Though fears of revolt occasionally arose, Saturnalia’s subversive potential was often restrained within the festival's boundaries.

The festival’s origins tied back to a utopian myth. According to Justinus, quoting the Historiae Philippicae of Pompeius Trogus:

“The first inhabitants of Italy... lived under King Saturn’s righteous rule, where there was no private property, and all things were shared equally.”

Macrobius also linked Saturnalia to this "Golden Age," a time of universal prosperity and equality. In Lucian’s words:

“I take over the sovereignty again to remind mankind what life was like under me... when everyone was good, pure gold. There was no slavery, you see, in my time.”

While the Saturnalia echoed this mythical equality, the political adoption of the Golden Age imagery during Augustus’s reign conveniently ignored the reality of widespread slavery. Despite the propaganda, the Saturnalia served as a ritualized reflection of these utopian ideals, reminding all Romans—free and enslaved—of their aspirations for justice and equality. (Meals in the Early Christian World Social Formation, Experimentation, and Conflict at the Table, by Dennis E. Smith and Hal E. Taussig)

A Carnival of Rebellion and Return

Saturnalia represents a temporary suspension of societal norms, celebrating equality and liberty while turning the established hierarchy on its head. The festival, as already mentioned, allowed slaves and masters to exchange roles, promoting a brief period of camaraderie and shared experiences.

According to anthropological theories by Victor Turner and others, the festival embodies a liminal phase, where participants are momentarily detached from their fixed societal positions and experience a unique sense of "communitas"—an egalitarian unity.

During Saturnalia, Roman citizens wore plain attire, and both masters and slaves donned the pileus. Rituals included sacrificing bulls, unfettering Saturn’s statue, and appointing a temporary "King of Saturnalia," whose whims everyone had to obey. While this antistructure briefly dissolved societal distinctions, participants reverted to their usual roles after the festival.

Victor Turner’s concept of liminality suggests such rituals expose the artificiality of societal hierarchies, allowing participants to experience an unstructured, egalitarian state. However, unlike transformative rites of passage, Saturnalia did not lead to lasting social change.

Instead, it was a sanctioned escape from reality—a fleeting carnival where rebellion and revelry coexisted with the inevitability of returning to normalcy. This temporary inversion of roles, celebrated with feasting, gambling, and role reversals, reinforced rather than dismantled the existing social order. (The Upside-Down World of the Saturnalia: A Carnival or a Pilgrimage?, by Ms. Samragngi Roy)

Saturnalia and the Evolution of Christmas: From Pagan Festivity to Christian Celebration

In her work "The Roman Saturnalia and the Survival of its Traditions Among Christians", Orsolya Tóth (the piece is Published by the Institute of History, University of Debrecen) delves into the historical and cultural origins of Saturnalia, and explores its transition into Christmas under Christian influence. She provides a comprehensive examination of the carnival’s evolution, tracing its roots, rituals, and eventual adaptation into Christian traditions.

It initially begun as a sowing festival, held to honor Saturn. The festival, marking the completion of winter planting, originally lasted one day, on December 17. By the 1st century BCE, however, it had expanded into a week-long celebration, running from December 17 to 23. Poets like Novius captured the festive length in lines like, “Once eagerly awaited, the seven days of Saturnalia arrive.”

During this time, the feast coincided with other agricultural festivals, such as Consualia (celebrating the god of harvest, Consus) and Opalia (dedicated to Ops, the goddess of abundance). These overlapping feasts emphasized the agricultural roots of Roman society and symbolized gratitude for the harvest. Over the centuries, the celebrations evolved, with Saturnalia becoming less tied to its agrarian origins and more focused on social and cultural rituals.

Tóth explores various accounts of the festival's origins, as recorded by Roman authors like Macrobius. Some traced it back to the Greek festival of Cronia, while others tied it to specific moments in Roman history, such as the dedication of Saturn's temple during the reign of Tullus Hostilius or Titus Larcius.

The temple, symbolizing Saturn’s legacy, also served as Rome’s treasury, underscoring the god’s association with abundance and communal wealth. Saturnalia was often referred to as the festum omnium deorum principis (the feast of the prince of all gods), reflecting Saturn’s prominence in Roman religion.

Macrobius, drawing from ancient traditions, suggested multiple theories regarding the festival’s origins. He favored an interpretation that depicted Saturn as a historical figure who brought agricultural knowledge and societal organization to early Italians, transforming chaos into order.

During its festivities, (as already mentioned above) the hierarchical structure of Roman society was temporarily dismantled. Slaves dined with their masters, and symbolic acts, such as exchanging roles, reinforced the theme of equality. Citizens wore the pileus, a cap symbolizing freedom, to represent their shared status as equals. Public institutions, schools, and courts shut down, marking a collective pause from the usual order.

The festival culminated on December 23 with the Sigillaria, a day dedicated to gift-giving. Clay figures and candles were exchanged, symbolizing light and renewal. These customs reflected the festival’s broader themes of generosity, community, and transformation. As Tóth notes, Saturnalia’s association with light and renewal made it particularly adaptable to Christian reinterpretation.

Its timing near the winter solstice aligned with the symbolic birth of Jesus as the "light of the world."

A Christian cross during a winter sunset. Credits: GuentherDillingen from pixabay, by Canva

Early Christians adopted and recontextualized many Saturnalian traditions, such as candle lighting, gift-giving, and festive meals, into their celebration of Christmas. This transition allowed pagan customs to persist in a Christianized form, ensuring their survival even as the Roman Empire became increasingly Christianized.

She highlights how, during the 4th and 5th centuries, Christian leaders worked to integrate these customs into the Christian calendar. Pope Leo the Great, for example, drew parallels between the birth of Christ and the renewal of light, framing Jesus as the bringer of salvation and a new world order. His sermons emphasized the spiritual significance of benevolence and reconciliation, aligning with Saturnalia’s ideals while infusing them with Christian theology.

While its secular elements, such as revelry and feasting, persisted, its deeper themes of peace and solidarity found new expression in Christmas. The Christian reinterpretation transformed Saturnalia from a celebration of abundance and liberty into a reflection of divine grace and the unity of humanity under Christ. Tóth concludes by noting that this synthesis of pagan and Christian traditions not only shaped Christmas but also preserved the original Roman festival’s essence, highlighting the enduring importance of community and generosity, for the survival of civilization.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: