Tyrian Purple: The Royal Dye of the Ancient World and the Secrets of Murex Extraction

From crushed shells to royal robes, the journey of murex purple dye reveals an industry as laborious as it was prestigious. This ancient craft, rooted in the rocky shores of the Mediterranean, blended biology, industry, and symbolism into a color that signified power, piety, and the price of empire.

In the ancient Mediterranean world, one color reigned supreme: Not gold, not silver—purple. Revered for its deep, rich hue and its resistance to fading, purple became synonymous with imperial power, sacred authority, and economic prestige.

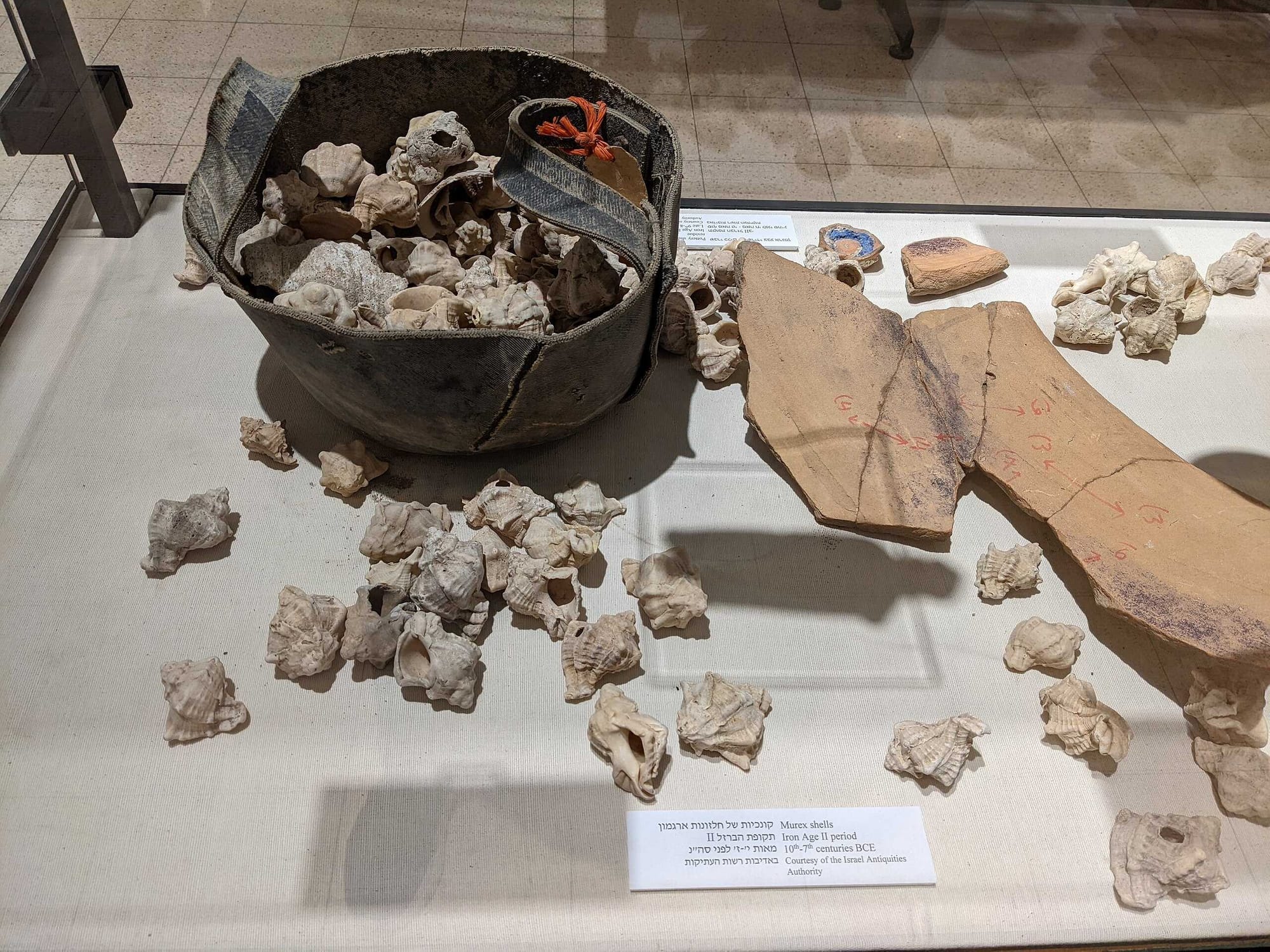

But behind this noble color was a laborious, malodorous process, steeped in skill and secrecy. Extracted from the glands of sea snails—particularly species of the Murex genus—this dye, often referred to as Tyrian or royal purple, required expertise and enormous resources to produce.

A Color Worth an Empire: The Allure of Tyrian Purple

To the ancient eye, few hues rivaled the deep, lustrous tones of purple. Associated with royalty, religious devotion, and imperial prestige, purple cloth—particularly the famed “Tyrian Purple”—held symbolic and material value.

Ancient Greeks and Romans did not simply wear purple; they revered it.

A painting by Theodoor van Thulden, depicting the myth behind the Discovery of Purple by Hercules and his dog. Public domain

But beyond the visual opulence lay a hidden industry of staggering proportions and biological intricacy. The production of this dye from sea snails of the Murex genus required complex procedures, keen knowledge of natural processes, and a great deal of labor. So prized was the final product that it became a signifier of divine authority and absolute power.

A Secret in the Shell

In a world where color carried rank, purple stood apart—not merely as pigment, but as prestige. Its origins, however, lay far from the palaces and temples it adorned. Along the wave-beaten coasts of the Mediterranean, small carnivorous sea snails of the Muricidae family concealed a remarkable biochemical secret.

When the mucus from these mollusks was exposed to air and sunlight, it transformed through a series of reactions into a dye of exceptional brilliance and permanence. The process was neither simple nor clean. It demanded tens of thousands of snails, careful extraction of a tiny gland, controlled fermentation, and sun-drenched exposure to release the vibrant purple from the sea.

Unlike other ancient dyes—such as saffron yellow from the crocus flower, or reds derived from madder root—murex purple could not be grown or harvested in fields. It was sourced from the sea, hidden within living organisms, and could not be imitated with ease.

Image #2: A composite image showing the various stages of crocus, from the flower, to the precious dried stigmas and the resulted yellow powder, used in ancient dyes. Credits: beats3, pressdigital from Getty Images, Billion Photos, by Canva

While plant-based dyes faded or bled with time, murex purple bonded to fibers with extraordinary tenacity, growing richer with age. It resisted wear, sunlight, and washing, and thus came to symbolize permanence, power, and exclusivity. Its brilliance was matched only by the cost and labor required to produce it, setting it apart as a mark of elite distinction.

Only three known species—Hexaplex trunculus, Bolinus brandaris, and Stramonita haemastoma—produced the compound in sufficient quantities for dyeing. And only those who controlled the know-how and labor to process them could access the result.

Because the output was small and the effort immense, the dye quickly became synonymous with wealth and ceremonial power. In many ancient societies, to wear purple was to claim authority—not just in life, but in death. (Shell Purple-Dye Production in the Mediterranean Basin and Environs, by David S. Reese)

Crushed and Buried: Archaeological Traces in Greece

The Greek mainland reveals the physical legacy of this luxurious industry with striking clarity. At Thessaloniki Toumba, archaeologists uncovered tens of thousands of crushed Hexaplex trunculus shells, deposited in layers spanning from the Middle Bronze Age into the Early Iron Age.

While some shells may have served as food or ornament, the overwhelming majority were shattered in a pattern characteristic of dye extraction. Nearby, at Derveni, a clay substance containing murex dye was discovered within a funerary container—possibly medicinal or ritual in use.

In East Lokris, the tidal islet of Mitrou preserved heaps of murex fragments across several Late Helladic and Protogeometric contexts. Some areas appeared to function as dye installations, marked by clusters of shells weighing several kilograms, situated near architectural thresholds and courtyards. A similar pattern emerged at Magoula Pevkakia near Volos, where shell deposits found alongside kilns indicated an organized, possibly communal, dye workshop.

Perhaps the most evocative find came from Aigai (Vergina), where the remains of royal tombs told a story in color. Cremated bones had been wrapped in cloth stained deep purple—most likely from murex dye. Although the fibers had long since disintegrated, the hue remained vivid on the bones and larnakes.

Chemical tests confirmed the presence of shell-based purple pigment, reinforcing the idea that purple textiles were integral to elite funerary practice. Other tombs, such as those at Hagios Athanasios, Mieza, and Pella, incorporated murex pigment directly into their painted walls.

At the Kerameikos Cemetery in Athens, the burial of Hipparete, Alcibiades' granddaughter, preserved traces of murex-dyed fabric fused to a bronze vessel. Similar textile finds occurred in Maroussi and Kalyvia—each fragment a quiet testament to the dye’s enduring symbolism in Classical funerary tradition.

In Eretria, thick middens of crushed shell sat near basins and vats—likely remnants of an industrial-scale operation from the Hellenistic or Roman period. From wall paintings to burial shrouds, the presence of purple was more than decorative. It was a statement of identity, privilege, and passage. (Shellfish Purple Colour in East Mediterranean: A Gazetteer of Sites, by David S. Reese)

Workshops in Stone and Bone

The Aegean islands offer some of the most vivid material evidence for purple dye workshops. At Cape Kolonna on Aegina, a Late Bronze Age facility yielded crushing tools, vats, and thousands of murex shells, all linked to a standardized system of dye extraction.

The crushed shells were so densely layered that they formed distinct midden zones, some separated from domestic debris, suggesting designated production areas.

A possible representation of a group of ancient workers breaking the murex shells, to harvest their precious glands. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Sora

On the island of Chryssi, off the southeastern coast of Crete, excavators identified installations dedicated to dye-making. These included stone basins, pounding tools, and channels for liquid runoff, all found alongside masses of crushed shell.

Nearby at Pefka, researchers uncovered plastered workspaces, ceramic basins, and residue-smeared containers. The layout of these spaces mirrored one another in form and function, implying that the process had been formalized. Each installation featured stages for shell cleaning, fermentation, dye extraction, and possibly textile immersion.

Across these sites, chemical analysis—using high-performance liquid chromatography and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy—confirmed the presence of brominated indigo, the main component of murex purple. These workshops demonstrate not only technological expertise but also cultural investment in the craft. (Chryssi and Pefka: The Production and Use of Purple Dye on Crete in the Middle and Late Bronze Age, by Apostolakou, Brogan, Betancourt, and Mylona)

In these coastal economies, the production of purple dye was integrated into social and religious life, and likely linked to external trade.

A Broader Mediterranean Palette: Italy, Spain, and Beyond

In Italy, purple dye production appears in both Bronze Age and Roman contexts. At Coppa Nevigata in northern Apulia, layers of shell debris span several centuries, from the Proto-Apennine through the Apennine periods. The scale is striking—tens of thousands of Hexaplex trunculus shells crushed, sorted, and deposited in stratified heaps. These remains are among the earliest known examples of murex-based dye production in the Western Mediterranean.

At Monte Circeo, a Roman-period shell midden stretches over 60 meters, packed with deliberately broken murex shells. Similar deposits have been found at Taranto, long known through historical sources as a center for dye manufacture. Descriptions from the 18th century noted entire hills composed of shell fragments, particularly Bolinus brandaris, pointing to a craft practiced at industrial scale.

At Aquileia, in the northeast of the peninsula, crushed shells were found beneath mosaic floors—possibly reused as filler. Further south in Campania, a mound of crushed murex at Cumae aligns with Imperial-era dye activities. Pompeii’s evidence is more modest: a few hundred shells survive in museum collections, though ancient sources occasionally link the city with purple dyeing.

In Spain, murex processing appears at coastal sites with Punic and Roman layers. At Carthago-Nova (Cartagena), deposits include a jar filled with crushed shells and vast accumulations associated with the amphitheater. The surrounding areas yielded over 3,000 murex shells across five archaeological phases, reflecting an ongoing dye economy from the third century BCE into the early Imperial period.

The Balearic Islands preserve perhaps the most concentrated evidence outside the Levant. At Canal d’en Martí and Cala Olivera, shell middens stretch several meters in length, containing tens of thousands of crushed Hexaplex specimens. Kilns, vats, and residue-covered tools confirm these as production sites.

Analysis of the stratigraphy, species distribution, and shell condition all point to a primary function: dye extraction and export. The proportion of murex to food shells is so high that subsistence activities can be ruled out. These workshops operated on a scale capable of supplying elite markets well beyond the islands. (Shell Purple-Dye Production in the Mediterranean Basin and Environs, by David S. Reese)

The Purple Line: Eastern Mediterranean and Levantine Shorelines

On the Levantine coast, purple dye production reached its most sophisticated and legendary form. At Tyre and Sidon, crushed shell mounds accumulated over centuries, some measuring several meters high.

These ancient Phoenician cities gave their name to the dye itself—Tyrian purple—and their legacy endures in both archaeological and textual sources. Shell debris found along harbors and promontories reveal where dye vats once stood, their contents poured out into the sea long after the color had been absorbed into cloth.

At Tel Shiqmona near Haifa, the ruins of a dye installation include work surfaces, fermentation vats, and thick layers of shell debris. The layout of the facility mirrors that of other coastal workshops, but the richness of the shell assemblage—alongside amphorae and transport vessels—suggests production for export as well as local consumption. At Dor and Tel Kabri, crushed shells mingle with ceramic vats and plastered basins, reinforcing the narrative of coastal industrialization centered on murex dye.

More sites, from Tell Keisan to Akko, confirm that the coast from Syria to Israel was dotted with small- to medium-scale producers. Even at sites where no installations survive, the presence of purple pigment in wall paintings and burial shrouds speaks to the dye’s broad cultural resonance. (Shellfish Purple Colour in East Mediterranean: A Gazetteer of Sites, by David S. Reese)

North African Shores and the Desert Dye

Along the North African coast, Carthage and its colonies provide compelling traces of the purple dye industry. Early modern accounts describe massive shell mounds near the ancient city, and while excavations have only sampled these deposits, the shell species and concentration are consistent with large-scale murex processing.

At Sabratha and Leptis Magna, Roman-period layers yielded crushed Bolinus shells, often located near workshop zones and harbors. Further inland, the trail grows thinner. In Egypt, fragments of purple-dyed linen have been found in Coptic tombs, but their origin remains uncertain. Chemical degradation and mixing with plant-based dyes have obscured definitive identification.

Egypt may have imported the dye itself—or more likely, purple garments—from Levantine and Aegean producers. The absence of shell middens along the Nile suggests that if murex dye was used here, it was not made locally. (Shell Purple-Dye Production in the Mediterranean Basin and Environs, by David S. Reese)

Throughout the ancient Mediterranean, purple was more than a color—it was a language of power. The dye’s creation demanded the convergence of biology, labor, chemistry, and trade. Its users were not merely consumers of beauty, but participants in a network of specialized knowledge, skilled practice, and unrelenting effort.

What endures today are the remnants: crushed shells buried in middens, stained walls, and silent basins. Together, these fragments form a vibrant composition of ancient ambition—one written not in gold or stone, but in the royal shadows of the sea.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: