Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus: Father and Son, in the Shadow of Crisis

Trebonianus Gallus and his son Volusianus ruled Rome for barely two years, beset by plague, invasion, and revolt. Their swift rise and violent fall reveal the empire’s fragility in the crisis of the third century.

The mid-third century was an age when emperors rose and fell with dizzying speed, their power determined less by policy than by the temper of the legions. Among those fleeting rulers were Trebonianus Gallus and his son Volusianus, a father-and-son dynasty whose brief reign mirrored the chaos of the times.

A Dynasty of Two Years

The mid-third century thrust upon Rome a series of rulers ill-prepared for the storm of crises surrounding them. With dangers erupting inside the empire and on distant frontiers, the task of governance became nearly impossible. Leadership was fleeting, the record of their reigns fragmentary, and their reputations often judged more harshly than their circumstances warranted.

A telling example is offered by the joint rule of Trebonianus Gallus and his son Volusianus (251–253 CE). For barely two years, they faced disaster on every side: Gothic invasions in the Balkans, Sasanian advances in the East, internal unrest in the capital, and a plague that refused to loosen its grip on Rome.

The crisis that brought Gallus to power began with catastrophe. In June 251, Emperor Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus were cut down at Abrittus in Lower Moesia, victims of the final surge of Gothic raids led by Cniva. In the wake of this humiliation, the legions on the Danube proclaimed as emperor their commander, Trebonianus Gallus, governor of the province.

With him, they raised his son Volusianus, presenting a new dynasty to fill the void.

A statue of Emperor Trebonianus Gallus, from Antakya Archaeology Museum. Credits: Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0

The sources offer little detail about this change, repeating only that it was the soldiers’ choice that made them emperors. Some ancient writers even whispered that Gallus had betrayed Decius, boasting of his role in the defeat. Yet this theory falters: it is hard to imagine soldiers elevating the very man accused of causing their disaster, especially while Decius’ surviving son, Hostilianus, remained in Rome. More likely, the emperor and his heir perished in the confusion of battle, and Gallus’ elevation was the army’s desperate response to preserve order on the frontier.

The Rise of a New Dynasty

Once secured as emperor, Gallus made peace with Cniva. The treaty brought a temporary calm to the Danubian frontier, though it was criticized both in antiquity and by modern scholars as hasty and humiliating. The Goths were allowed to depart with their plunder and captives, and Gallus promised them annual tribute from the empire’s coffers. Yet this uneasy settlement gave Gallus and Volusianus the time they needed to travel to Rome and present themselves before the Senate.

There, Gallus sought to consolidate legitimacy by binding himself to the fallen dynasty. Decius’ surviving son Hostilianus, already honored with imperial rank, was adopted by Gallus and confirmed as Augustus. Volusianus, meanwhile, was granted the title of Caesar, the clear heir-apparent. Coins and official acts reflected this new arrangement: Rome would be ruled not by one emperor but by a coalition of families, symbolizing stability after chaos. Gallus even ordered the deification of Decius, giving divine honors to his predecessor.

An unusual silence surrounds Gallus’ wife, Afinia Gemina Baebiana, the mother of Volusianus. Unlike the empresses before her, she never bore the title of Augusta after her husband’s accession. Whether she had died early or was estranged from Gallus is uncertain. One theory holds that her absence was intentional: perhaps Gallus chose to leave the title with Herennia Etruscilla, Decius’ widow, who continued to be honored as Augusta. If so, this would have been a remarkable act of deference, signaling Gallus’ policy of merging his line with that of Decius rather than displacing it.

Plague and the Death of Hostilianus

The arrangement of shared rule was short-lived. Within months of Gallus’ arrival in Rome, the empire was struck by the relentless plague (Plague of Cyprian) that had already been raging for years. Among its victims was the young Augustus Hostilianus, whose death was variously dated by ancient writers to midsummer or late autumn of 251 CE.

Whether he died in June, August, or later in the year, the result was the same: the fragile balance Gallus had crafted collapsed. Hostilianus’s death left Gallus and Volusianus as sole rulers, and the relationship with Decius’ memory grew more complicated. While Gallus had initially honored his predecessor and embraced his family, Zosimus later claimed that the new regime began to view Decius and his sons as potential threats to their authority.

What is clear is that Gallus and Volusianus now had to govern alone, with only the prestige of their newly created dynasty to support them. The plague itself continued to devastate the empire. It had begun under Philip the Arab and by Gallus’ reign had already consumed half a decade of Roman life. Contemporary accounts describe its toll as no less ruinous than the wars of the period. Production faltered, armies weakened, and resources dwindled.

In response, the emperors turned to divine aid, issuing coins invoking Apollo Salutaris and the piety of the Augusti, appealing to the gods for deliverance. Some sources suggest Gallus even revived aspects of Decius’ religious policy, though without the systematic persecution of Christians that had marked his predecessor’s reign.

Some scholars believe this statue to belong to Maximinus Thrax, instead.

War on Two Fronts

Even as plague tore through Rome, Gallus and Volusianus faced mounting dangers on the frontiers. To the East, King Shapur I of the Sasanian Empire launched a new offensive. Violating the treaty once arranged with Philip the Arab, Shapur seized Nisibis, forced Armenia’s ruler Tiridates II into Roman protection, and pressed into Mesopotamia. His Res Gestae boasts of a devastating victory at Barbalissos, claiming that 60,000 Roman soldiers were slain and more than thirty cities captured. Though such numbers may be inflated, they point to the scale of disaster.

A controversial figure in this eastern struggle was Mariades, a Syrian notable who defected to the Sasanians. Ancient accounts describe him as betraying Roman lands to Shapur, providing both intelligence and leadership that aided the invasion. Whether exaggerated or not, his role underscored the vulnerability of Rome’s provinces when local elites turned against the imperial center.

Meanwhile, the Goths renewed their raids across the Danube, pushing deeper into the empire. Macedonia, Greece, Asia Minor, and even Italy itself felt the pressure of their incursions. Ancient authors accused Gallus of negligence, claiming he remained idle in Rome once his rule was secure. Yet inscriptions and coinage suggest otherwise: both emperors were engaged in imperial duties beyond Italy, and Volusianus in particular may have been active in the East. Gallus relied on commanders such as Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus to hold the Danubian line, a decision that would soon bring fatal consequences.

Coinage and Imperial Image

Although the reigns of Gallus and Volusianus left only a thin trail in written history, their coinage speaks in abundance. Struck in Rome, Mediolanum, and Antioch, their issues allow us to trace not only chronology but also the image they sought to project in the midst of crisis.

The earliest coins reflect the uneasy compromise after Abrittus. Hostilian appears as Augustus alongside Gallus, while Volusian is presented as Caesar, and Herennia Etruscilla continues as Augusta. After Hostilian’s death from plague, Volusian’s promotion to Augustus is confirmed in the coinage, while Herennia disappears from the series.

Themes of the reverses reveal how father and son attempted to reassure a shaken empire. Their coins proclaim Concordia Augustorum (harmony of the emperors), Virtus and Victoria (valor and victory), Pax (peace), Pietas (piety), and Felicitas Publica (the happiness of the state). Apollo Salutaris and Salus feature prominently, invoking divine protection against the plague that was ravaging Rome. The pairing of types — such as Annona and Aequitas — suggests concern for stability of supply and fairness in distribution, key anxieties when famine threatened alongside pestilence.

The imagery also highlights Volusian’s active role. Certain types depict him not merely as heir but as a full partner in rule, performing priestly duties or carrying the symbols of peace. This emphasis may reflect a deliberate effort to establish him as a co-emperor capable of acting on equal footing with his father. Even the use of the star symbol on some issues has been interpreted as a gesture toward the divinized memory of Decius and his family, further binding Gallus’ dynasty with that of his predecessor. (The reigns of Trebonianus Gallus and Volusian and of Aemilian, by Harold Mattingly)

In sum, the coinage of Gallus and Volusian provides a striking counterpoint to their fragile political position. While their reign was brief and troubled, the coins paint a portrait of emperors striving to embody unity, piety, and resilience in an empire beset by calamity.

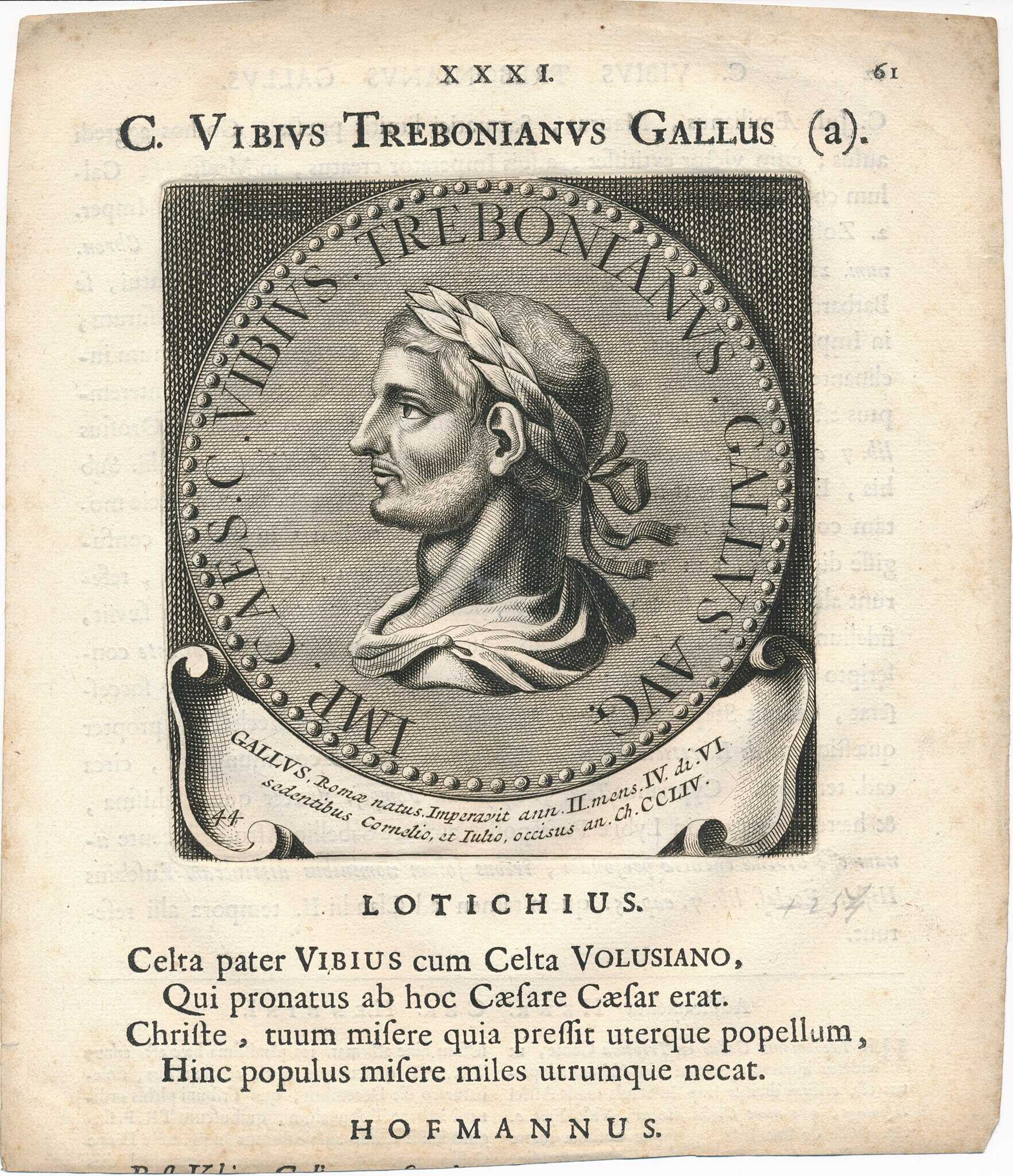

Image #1: An engraving in medaillion of Roman Emperor Trebonianus Gallus. Public domain. Image #2: Possible Roman bronze portrait of Trebonianus Gallus. Credits: Dan Diffendale, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Revolt and Assassination

While Gallus attempted to balance plague at home and invasions abroad, unrest brewed among the Danubian legions. The Gothic raids had resumed, and Rome’s soldiers longed to redeem their honor. When Gallus’ commander in Moesia, Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus, stopped paying tribute to the Goths and instead led the legions to victory beyond the Danube, their loyalties shifted swiftly. The army acclaimed Aemilian as emperor, and with momentum on his side, he marched toward Italy.

Gallus and Volusianus responded by calling on reinforcements from the Rhine under the senator Valerian, but they never lived to see them arrive. In the summer of 253, as they prepared to confront the usurper, their own soldiers turned against them. Near Interamna — or possibly further north at Forum Flaminii — both emperors were murdered by their troops. Their deaths marked yet another abrupt imperial turnover in an age defined by military acclamation and betrayal. (Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus (AD 251-253): Ruling the Empire in between the West and the East, by Lily Grozdanova)

The joint reign of Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus was brief, troubled, and ultimately doomed. Caught between the hammer of the Goths and the anvil of the Sasanians, their authority was further weakened by plague and discontent at home.

Yet their story is not merely one of failure: it reflects the impossible weight of governing an empire in crisis, when no victory could be decisive and no compromise secure. Their murder at the hands of their own men was less a personal downfall than a symptom of an age when emperors rose and fell with the shifting will of the legions.

In the aftermath, power passed swiftly to another. Valerian, then commanding in Raetia and Noricum, had been ordered by Gallus to bring reinforcements from Gaul and Germany. When word spread of the emperors’ deaths, his own men acclaimed him Augustus.

Advancing into Italy, Valerian’s presence alone was enough to sway Aemilian’s soldiers, who deserted their commander and killed him. Thus, from the collapse of Gallus and Volusianus emerged a new emperor — one whose reign would bring the empire both fleeting stability and unprecedented humiliation.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: