Thumbs Down to the Myth: The Truth behind Roman Arena Gestures

What were the actuals signs given in the Roman Arena of the past and how are they used now?

In popular culture, particularly in movies like Gladiator (2000), the emperor or crowd is often shown giving a "thumbs up" to save a gladiator and a "thumbs down" to condemn them to death. However, historical evidence suggests that the gestures used in the Roman arena were different from what we typically see portrayed.

What is the original meaning of the thumbs up and thumbs down gestures?

“These men once were horn-blowers and attendants at every municipal arena, known as trumpeters in every village. Now they present their own spectacles, and, to win applause, kill whomever the mob gives the “thumbs up”.

Decimus Junius Juvenalis; a.k.a. Juvenal, "Third Satire"

Juvenal mentions the Roman practice where spectators used their thumbs to vote on the fate of injured gladiators. Contrary to what one might assume today, a gladiator would not have welcomed a “thumbs up” (verso pollice) from the crowd; in Roman times, this gesture signified death, much to the audience's pleasure.

On the other hand, a thumbs down meant “swords down”

A gladiator laying down his arms, next to his incapacitated opponent. Illustration: Midjourney

This indicated that the defeated gladiator was more valuable alive and would be spared, likely to redeem himself in a future fight. This understanding challenges our modern use of the "thumbs up" sign.

Our reversal of this custom likely stems from the French artist Léon Gérôme, who misinterpreted the Latin word verso ("turned") as meaning "turned down" in his 1873 painting Pollice Verso. Gérôme’s depiction became so popular that his error became widely accepted, and it's unlikely that the original Roman meaning will ever be restored.

Before Gérôme, scholars supported the idea that a "thumbs down" signaled mercy for the defeated gladiator, urging him to "throw your sword down." A 1601 translation of Pliny equated the gesture with approval or favor, and John Dryden's 1693 translation of Juvenal’s Satires indicated that bending the thumb back, rather than down, was the signal for death.

When a gladiator was seriously wounded, the presiding judge would decide his fate based on the crowd's reaction. If the crowd showed their favor with a "thumbs down," the gladiator would be carried off to receive medical treatment. However, if they remained silent and gave a "thumbs up," it signaled his opponent to deliver the fatal blow, after which the corpse was removed like an animal.

The true meaning of Thumbs Down

Pollice verso or verso pollice, is a Latin phrase meaning "with a turned thumb," associated with gladiatorial combat in Ancient Rome. It refers to a thumb gesture used by Roman crowds to express their judgment on the fate of a defeated gladiator.

The exact gesture and its meaning conveyed by pollice verso have been the subject of ongoing scholarly debate till this day.

Anthony Corbeill, in his work, “Thumbs in ancient Rome: pollex as index”, -which is a cornerstone for understanding the historical context of the "thumbs up" and "thumbs down" gestures in Roman gladiatorial games- says that in Roman culture, the thumb—known as digitus pollex or simply pollex—played significant roles across various familiar contexts. It could serve as a symbol of good luck or possess an apotropaic (protective) function, exemplified by the well-known "fig" gesture.

Most notably, in the context most recognized by modern audiences, the thumb was utilized by spectators and Emperors in gladiatorial games to decide the fate of a defeated fighter, signaling whether he or she should be killed or spared.

However as we portrayed above, contrary to popular belief shaped by artistic interpretations and Hollywood films, scholarly sources present conflicting views and uncertainties about the exact appearance and meaning of this thumb gesture. Depictions vary widely: the thumb has been shown pointed upwards, downwards, concealed within the hand, directed towards the chest, and even placed between the middle and index fingers.

In an effort to clarify this ambiguity, Corbeill dives into the symbolic system of bodily gestures, emphasizing the thumb's role as an independent entity with its own distinct properties and significance. Latin literature consistently acknowledges the thumb's unique importance, a trait particularly pronounced in Roman texts. Overlooked visual evidence highlighting the thumb's perceived power further supports the linguistic claims made by Roman authors.

Specifically, Corbeill concludes that, contrary to prevalent discussions about the thumb gesture, the signal for death to a fallen gladiator involved pointing the thumb not downward but upward towards the sky. Conversely, if a gladiator had demonstrated sufficient bravery to merit survival, the gesture used by Romans resembled a closed fist.

Corbeill offers the most comprehensive analysis of the gesture, interpreting pollices premere in Pliny as "to press the thumbs." He concludes that pressing the thumb down on the index finger of a closed fist signified mercy. In contrast, the opposite gesture, an erect thumb pointing upward, is how he interprets infesto pollice in Quintilian, where the hostile thumb indicated death. This aligns with the definition found in Lewis and Short's A Latin Dictionary (1880): "To close down the thumb (premere) was a sign of approbation; to extend it (vertere, convertere; pollex infestus) a sign of disapprobation."

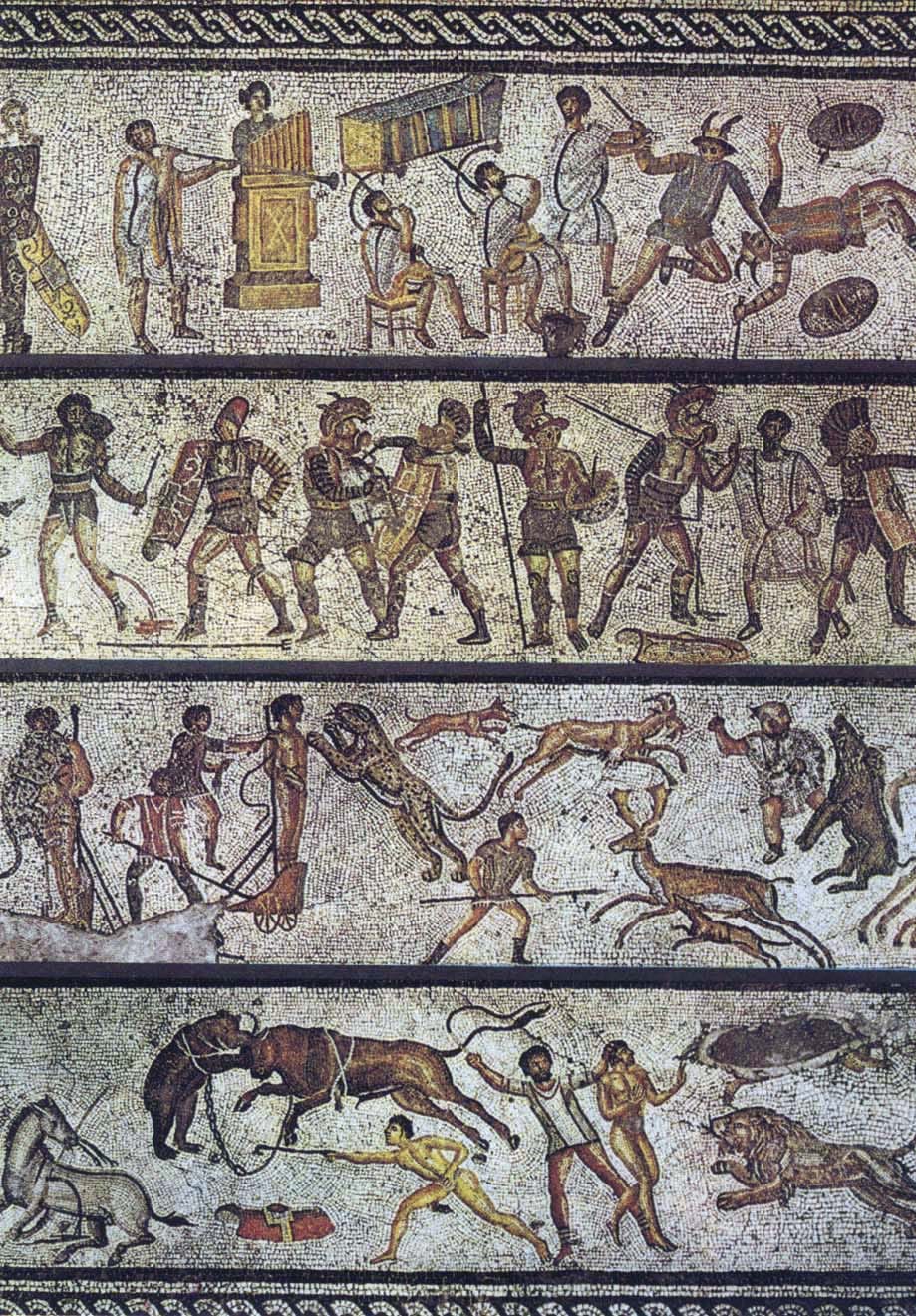

Interestingly, Corbeill suggests that it wasn't the victorious gladiator who determined the crowd's reaction, but rather the producer (editor) of the games, who then conveyed the decision to the judge. Corbeill argues that the producer's attention might have been drawn by music in the arena, possibly the sound of a horn, as depicted in the Zliten mosaic.

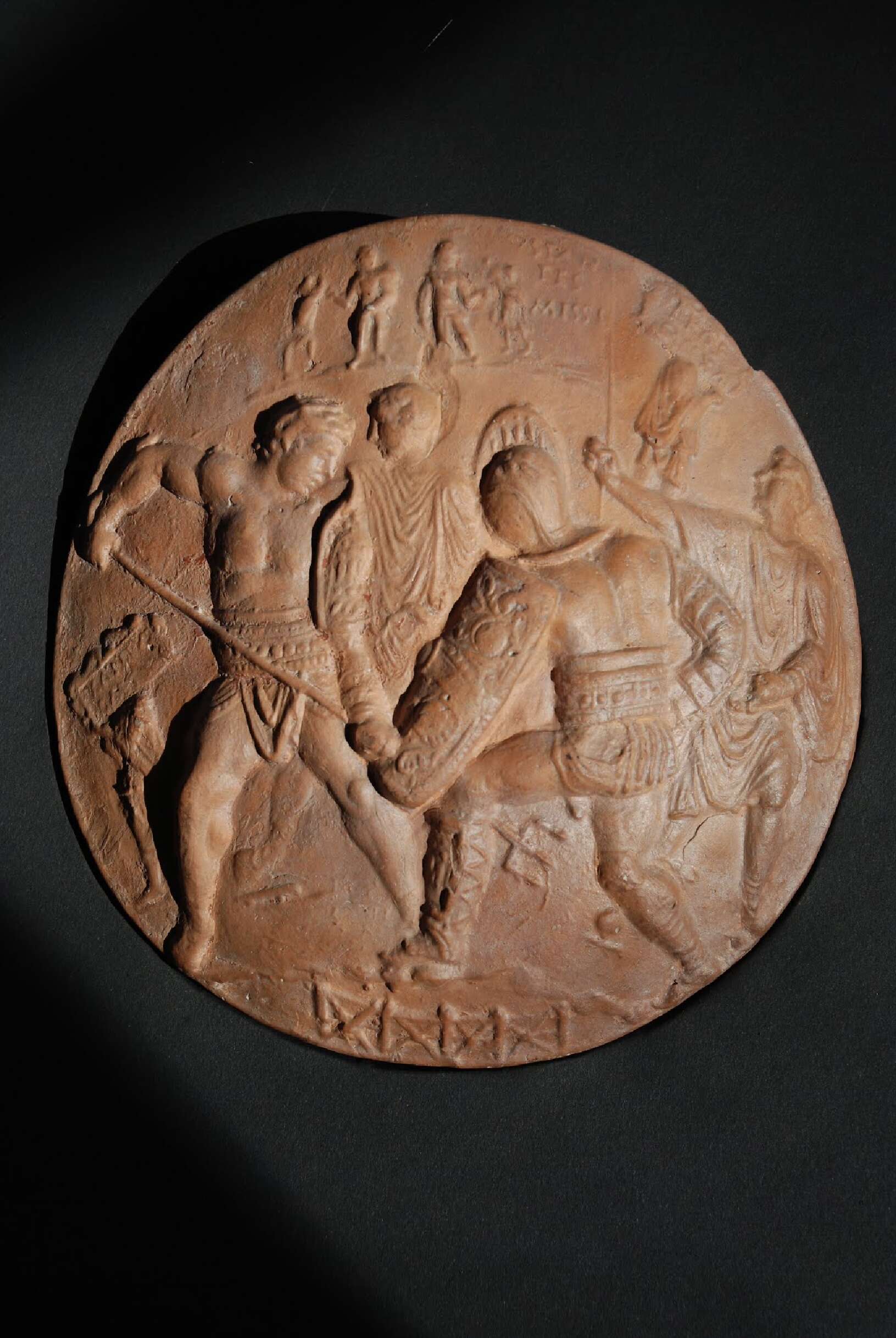

Corbeill also uses the Médaillon de Cavillargues to support his argument that the thumb pressed down on the fist was a gesture of mercy. He proposes that the rod seen in the medallion is not being held by the person on the right, but by the figure in the middle, thereby allowing the fist to make the mercy gesture.

Moreover, at the top of the medallion, the inscription STANTES MISSI ("released standing") indicates missio, or release from the arena, for the two combatants, identified in the background as Xantus, victor in fifteen contests, and Eros, victor in sixteen. The medallion, which depicts a contest between a retiarius and a secutor, dates to the late second or early third century AD and is housed in the Musée Archéologique (Nîmes).

Continuing with Corbeill, he states that gestural language has a tendency to endure longer than spoken language, with many gestures maintaining their meanings across different cultures and centuries. For instance, gestures like the "fig" or the outstretched middle finger have kept their significance since Roman times. Similarly, certain ritual gestures, such as crossing fingers for luck or making the "horns" gesture, have been passed down through the ages.

History of the Roman Gestures

This enduring nature of gestures suggests that specific ones, particularly from the Roman Empire, would be preserved in culturally consistent settings. An illustrative example is provided by Quintilian, a first-century rhetorician, who confidently described the hand gesture used by the Greek orator Demosthenes, despite it having occurred 400 years earlier. Quintilian's confidence was based on the intrinsic suitability of the gesture, rather than on any external proof.

Further reinforcing this idea of continuity, Roman etymologists like Ateius Capito believed that the Latin word for thumb (pollex) was derived from its association with power. This connection between the thumb and power is reflected in Latin poetry, where the thumb often stands in for the entire hand in various activities.

Capito, along with later writers like Isidore and Lactantius, also ascribed moral and even divine qualities to the thumb, viewing it as superior to other fingers. Lactantius, in particular, praised the thumb as the "guide and moderator of all things," using terms usually reserved for describing the Christian god. This suggests that the thumb's perceived power had both physical and spiritual importance, as shown in its etymology and continued use over the centuries.

In Quintilian's discussion of rhetorical effect, he describes a threatening gesture:

"There is also a gesture, which consists in inclining the head to the right shoulder, stretching out the arm from the ear and extending the hand with the thumb turned down. This is a special favourite with those who boast that they speak "with uplifted hand"

Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria

While most commentators interpret this as a gesture where the thumb points downward, their interpretations are based less on Quintilian's wording and more on the assumption—explicit or implicit—that the thumb's final position should resemble the signal given for death in gladiatorial combat.

It is understandable why this gesture might be called "a hostile thumb," as in the Latin Anthology, where the conquered gladiator fears the crowd’s "hostile thumb" (infesto pollice):

"Even in the fierce arena the conquered gladiator has hope, although the crowd threatens with its hostile thumb."

Quintilian, Book 11 Institutio Oratoria

However, the death signal was not made by a downward-pointing thumb. In fact, closer examination of Quintilian’s description suggests the opposite.

First, when adopting the stance Quintilian describes—with the arm extended to the side—the natural position of the thumb is pointing upward, especially if the fingers are extended (as suggested by manum...extendit). Raising the hand and pointing the thumb downward creates an awkward and uncomfortable position.

Second, an upward-pointing thumb fits better with the context of Quintilian's description of those who speak "with uplifted hand" (sublata manu). The phrase sublata manu typically refers to a Roman with hands raised and palms facing upward.

If Quintilian intended to describe a downward-pointing thumb, it’s difficult to understand why he would use the term sublata. A raised hand and a downward thumb are contradictory. Therefore, a more accurate reading of Quintilian's description suggests that the "hostile thumb" points upward, and the infesto pollice mentioned in the Latin Anthology connects this gesture with the signal for death in the arena.

Prudentius, a Roman, Christian poet, supports the meaning of the thumbs up in his book “Against Symmachus” where he writes about a Vestal Virgin that is watching the games and writes:

"Then on to the gathering in the amphitheatre passes this figure of life-giving purity and bloodless piety [the Vestal], to see bloody battles and deaths of human beings and look on with holy eyes at wounds men suffer for the price of their keep.

There she sits conspicuous with the awe-inspiring trappings of her head-bands and enjoys what the trainers have produced.

What a soft, gentle heart!

She rises at the blows, and every time a victor stabs his victim’s throat she calls him her pet; the modest virgin with a turn of her thumb bids him pierce the breast of his fallen foe so that no remnant of life shall stay lurking deep in his vitals while under a deeper thrust of the sword the fighter lies in the agony of death."

Are we certain thumbs down was not a request for death?

Although the historical data point to that direction, and the evidence shared above show the same, we still do not have a definitive answer regarding the direction the audience’s thumbs pointed to indicate whether they wanted a gladiator to die. If an extended, turned thumb signaled a kill, what gesture did the audience use to spare the gladiator’s life? According to Martial, the crowd would appeal for mercy by either waving their handkerchiefs or shouting.

It’s possible that the gesture for mercy involved hiding the thumb inside the fist, known as pollice compresso or “compressed thumb.” Anthony Corbeill as we aforementioned, interprets Pliny’s phrase pollices premere to mean that pressing the thumb down on the index finger of a closed fist signified mercy.

In truth, there’s some speculation about the rationale behind these two gestures. First, it would be easier for the crowd to distinguish between them. Second, the gestures might symbolize the state of the gladiator’s sword: an extended thumb indicating that the audience wanted the victor to deliver a final blow, while a compressed thumb signaled the victor to sheath his weapon and show mercy to the defeated.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: