The Amazons in Roman Thought: From Fierce Foes to Fascinating Myths

The Amazons, at once feared and admired, stood at the edges of Rome’s imagination. In poetry, art, and history, they became shifting symbols of conquest, gender, and empire—figures through whom Romans defined themselves against the “other.”

Clad in armor and bearing bows, the Amazons stood at the edge of Rome’s imagination—women who fought like men, ruled without them, and defied the natural order as Romans understood it. To Roman writers, artists, and statesmen, these warrior queens were both a source of awe and a warning, embodying the allure and the peril of a world turned upside down.

Whether carved on sarcophagi, minted on coins, or woven into poetry, the Amazons became mirrors through which Romans examined conquest, gender, and the boundaries of their own civilization.

Rome and the Amazons: Myth, Power, and Identity in the Imperial Age

Modern scholarship has long examined how the Greeks used the Amazon myth to reflect their society and values. In contrast, the Romans’ engagement with Amazons—especially in literature and art—has received far less attention. Yet from the reign of Augustus in 27 BCE to that of Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE, Amazons appeared frequently in Roman works, serving as symbols in the creation of imperial identity after the upheavals of civil war.

The surviving material falls into two main groups. On the one hand, literary texts—by authors such as Virgil, Strabo, Pliny the Elder, Curtius, Plutarch, Arrian, and Pausanias—present Amazons in ways that celebrate the greatness of Rome and reinforce the emperor’s image. On the other hand, visual culture—statues, reliefs, sarcophagi, mosaics, pottery, and jewelry—adapts the Amazon figure for both public and private display.

Within these works, the Amazons could be portrayed in many guises: Trojan allies, warrior goddesses, native Latins, fiery Celts, proud Sarmatians, passionate Thracian queens, subdued Asian cities, or formidable Roman foes. Their imagery changed with the shifting concerns of the empire, blending political achievement, social identity, public memory, and imperial ideology.

A closer look at these sources reveals recurring themes and strategies: the adoption of earlier traditions, responses to contemporary events, and stylistic choices shaped by place and purpose. Amazons were not chosen at random—they embodied specific ideas that resonated with Roman audiences, reflecting the needs and anxieties of the age.

Before Rome’s own foundation legends, the Amazons were already established in Greek myth as an autonomous, warlike nation of women—figures created to be confronted and ultimately defeated by male heroes. Early narratives (the lost Aethiopis on Penthesilea at Troy; references in Homer; early iconography from Tiryns) portray them as formidable yet marked as “barbarian” and female, hence exceptional opponents.

By the sixth century BCE the Amazons occupy a liminal position between matriarchy and patriarchy, blending traits of both. Greek sources repeatedly stress their divergence from Greek gender norms: they fight, ride, hunt, and govern; they restrict marriage or childbearing to those who have proven valor.

“From that time the women of the Sauromatae kept their ancient way of life: they ride out to the hunt on horseback, with the men or without them; they go to war, and they wear the same clothing as the men.”

“As for marriage, their rule is this: no maiden is married until she has slain a man of the enemy; and some even grow old and die unwed, unable to fulfill the law.”

Herodotus, Histories

They privilege daughters and, in some accounts, maim or expose male infants. Writers such as Apollodorus and Hellanicus emphasize customs that invert Greek expectations of women and household order, reinforcing the Amazons as anti-polis outsiders.

Geographically, the Amazons are pushed to the edges of the known world.

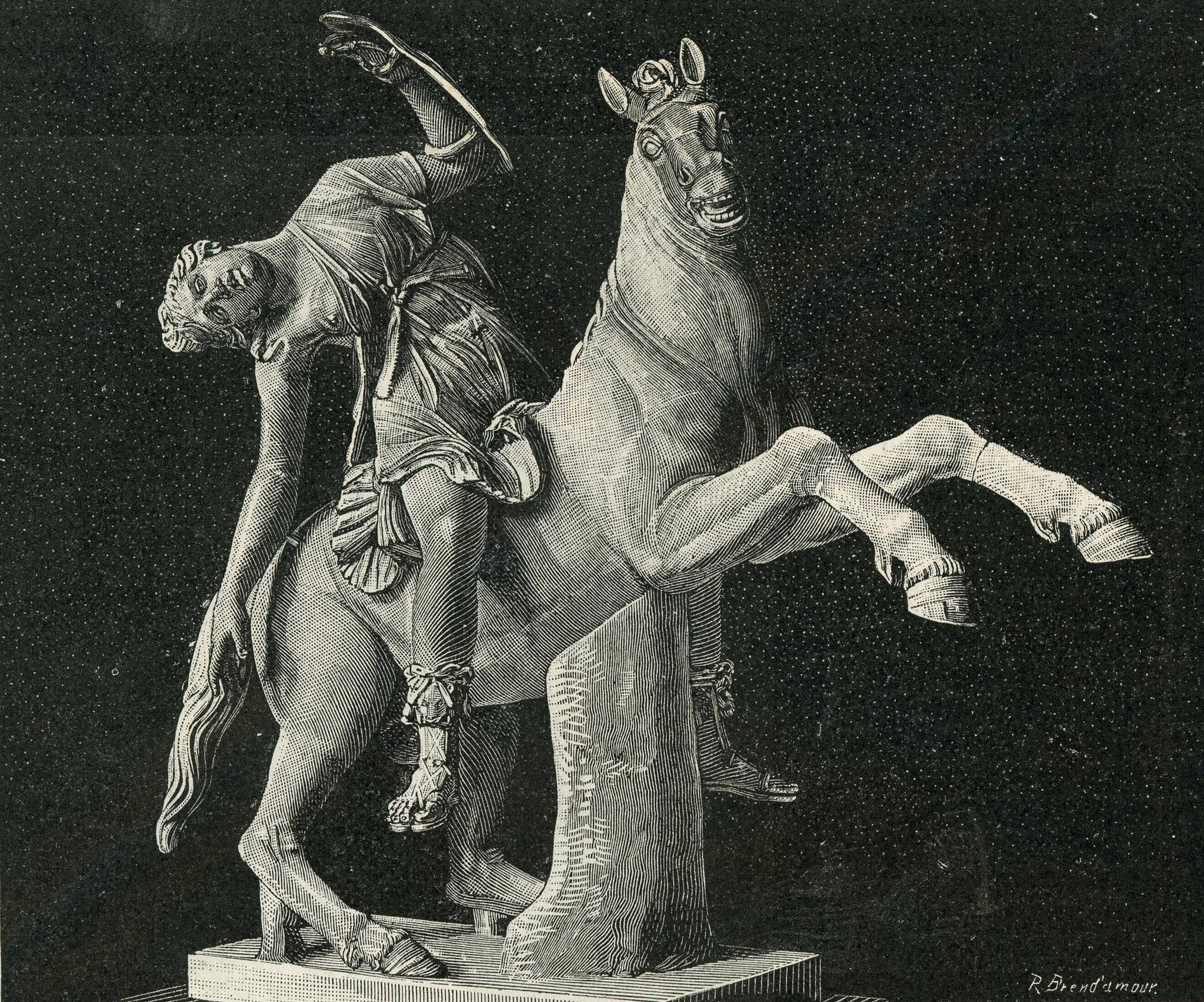

Dying Amazon on horseback, a hand woodcut (xylography) by Richard Brend'amour, based on the Roman copy of a Greek marble statue. Public domain

Different authors place them by the Thermodon, in the Black Sea region, Asia Minor, Libya, the Crimea, even as far east as Central Asia. Their remoteness mirrors their cultural otherness. Greek xenophobia—shaped by inter-Hellenic conflicts and Persian invasions—feeds this portrayal. In myth, heroes go out to meet them; the Amazons’ defeat validates Greek order and male authority.

Canonical episodes—Heracles’ ninth labor (the girdle of Hippolyte) and Theseus’ encounters—encode sexualized violence and abduction as mechanisms that reassert patriarchal control and assimilate the “deviant” female warrior into a normative framework. Fear (Phobos) is thematized: Amazon raids on Attica invert civic space and gender roles, dramatizing threats to Athenian hegemony until heroic counter-action restores it.

Athenian visual culture integrates this ideology. Amazonomachy imagery rises around the Persian Wars; its placement alongside Athena and on major monuments underscores how defeating Amazons becomes a civic emblem.

Across centuries the core traits remain stable: equestrian skill, double axes, distant homelands, and relentless warfare. Later receptions keep the motif alive; early modern travelers still speculate on real warrior women, and recent burials from southern Russia have been read by some as potential contexts for such traditions (while the historicity question remains complex).

Modern scholarship has parsed these myths through many lenses. Nineteenth-century readings (Bachofen) framed Amazons as residues of imagined matriarchies; iconographic studies tied Amazon battles to Persian-Greek conflict and personified “the other”; structuralists stressed binary oppositions and patriarchal anxiety; feminist and post-modern approaches variously emphasized either patriarchal suppression or the amplification of Amazon valor to magnify Greek victory. Across these debates, one constant remains: Amazon stories offered Greeks a flexible way to think about identity, gender, and outsiders.

Against this extensive work on Greece, treatment of Amazons in a specifically Roman context has been comparatively limited. Yet in the Roman Empire the myth persists and is repurposed. From Augustus to Marcus Aurelius, literature and art mobilize Amazon figures within imperial ideology: to imagine foundations and frontiers, to articulate Roman identity, and to frame domination over “barbarians.” Romans borrow Greek forms but adapt meanings to imperial needs.

Periodization matters. Under Augustus, Amazon imagery interacts with projects of unity after civil war and with models of pietas and virtus associated with Aeneas; authors like Strabo fold geography into imperial horizons, mapping known/unknown as civic pedagogy for rulers of borders.

Julio-Claudian eclecticism and Flavian recalibration see hybrid iconographies as Rome’s populations and religions mingle, complicating single political readings while confirming the motif’s popularity. Under the Adoptive Emperors, comparative uses of Greek and Roman Amazon encounters help stabilize and celebrate an established order, and the imagery broadens into more generic civic and personal commendation.

The defeated Amazon serves narratives of Roman success, yet the figure’s elasticity also exposes anxieties about outsiders and self-definition in a changing empire. Methodologically, mapping these shifts benefits from comprehensive iconographic corpora, which allow themes and motifs to be tracked across media (statues, reliefs, sarcophagi, mosaics, gems) and settings (public and private).

In short, the Amazon myth’s Roman afterlife mirrors Rome’s own negotiations of identity and power. The imagery changes with context, but its utility endures: a pliable symbol through which Romans could blend patriotism, civic memory, and imperial ideology—while retaining the essential, recognizable profile of the mythic Amazon.

Amazons in the Augustan Age: Myth, Politics, and the Making of Empire

After the civil wars and Actium (31 BCE), Octavian—soon Augustus—needed to stabilize Rome and forge a unified identity for an empire weary of conflict. He employed myth, art, and literature to create a shared consciousness rooted in victory, pietas, and Roman destiny. In this environment, the Amazons became a pliable symbol.

Their liminal identity—female but martial, admirable yet dangerous, barbarian yet noble—allowed Augustus’ propagandists to recast them as foils and mirrors for Roman power, drawing on Greek precedent but tailoring the imagery to imperial needs .

Virgil’s Aeneid and Camilla

Virgil, living through the Republic’s collapse and Augustus’ rise, infused the Aeneid with themes of conquest, order, and destiny. Among its characters stands Camilla, the Volscian maiden-warrior, explicitly likened to an Amazon. She embodies both rustic Italy and martial ferocity: armed with a myrtle spear tipped with metal, dressed in purple, adorned with golden ornaments, and devoted to Diana .

“Just as on the banks of Eurotas, or over the ridges of Cynthus, Diana trains her choirs… she carries a quiver on her shoulder, towering above all goddesses as she walks, and Latona’s silent joy thrills her heart: such was Camilla… One could outstrip the winds with her running; she might skim over the topmost blades of a field of grain without bruising the tender ears, or glide across the swelling sea without her swift feet touching the water.”

Virgil, Aeneid 11.855–869

Camilla defies gender norms—

“her hands had never grown accustomed to distaffs or the baskets of Minerva”

Virgil, Aeneid 7.1058–1060

—yet she is celebrated by her people and feared by enemies. Virgil stresses her virginity, her disdain for “women’s work,” and her liminal place between male and female roles . She achieves an aristeia in battle, slaying Trojans with Homeric ferocity, echoing Penthesilea’s doomed valor at Troy . Her eventual death, foretold by fate, foreshadows the downfall of Italian resistance and the destined triumph of Aeneas’ line.

For Roman readers, Camilla’s contradictory qualities—valor, beauty, hubris—reflected anxieties about outsiders, women, and barbarian defiance. Her defeat reinforced the inevitability of Rome’s supremacy, while her honor and bravery allowed Virgil to both admire and contain the Amazonian archetype within Augustan ideology.

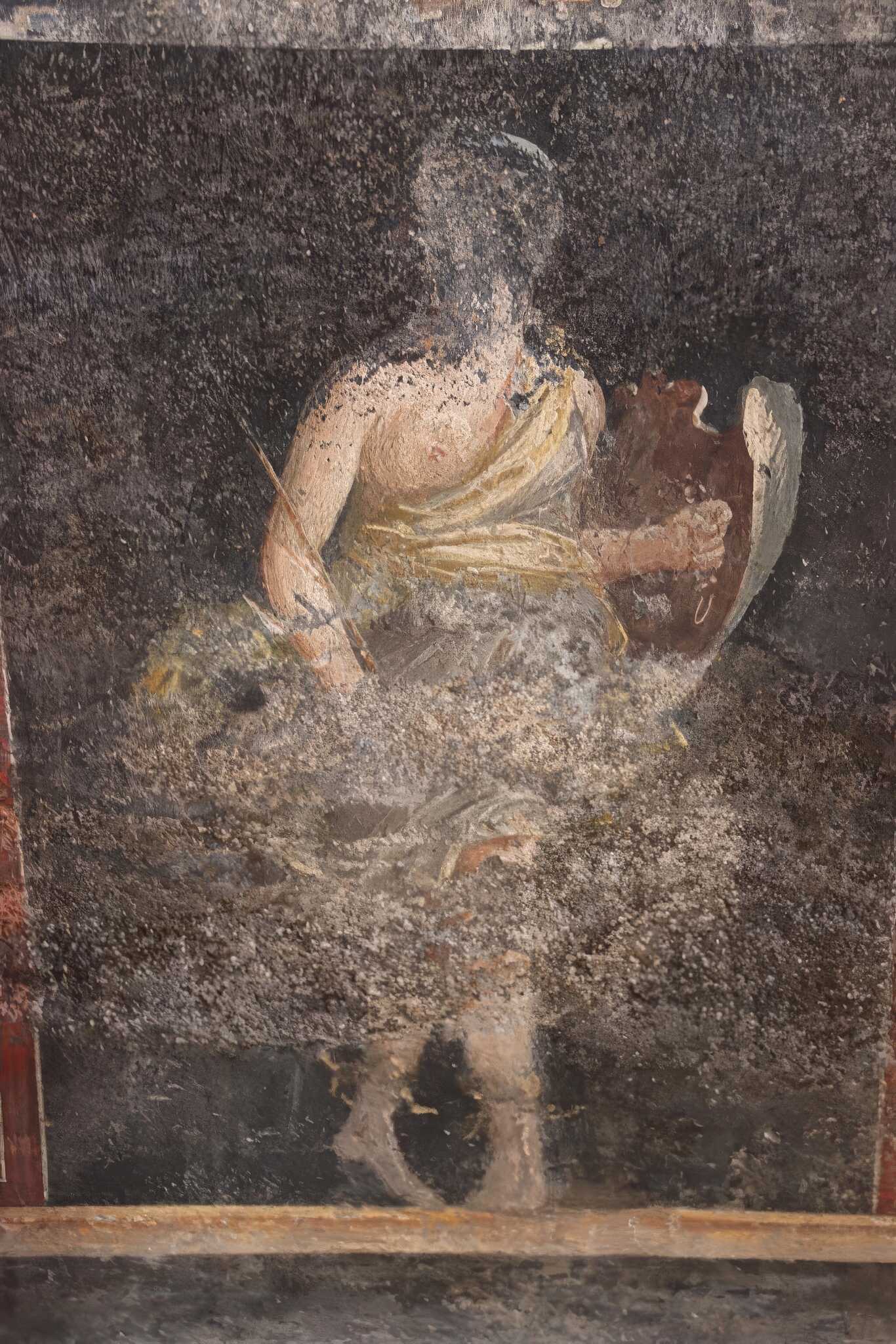

House of the Vettii in Pompeii, painted panels of three Amazons armed with a shield, holding ax and shield from plinth, and armed with a shield. Public domain

Strabo’s Geography

Strabo, a Greek intellectual writing under Augustus, crafted his Geography as a compendium for Roman elites, blending Greek ethnography with Roman imperial vision. He treated Amazons with skepticism yet fascination. He collected diverse traditions—placing their homelands around the Black Sea, Thermodon, or even Libya—and noted their customs of rejecting patriarchy and engaging in war .

While Strabo doubted the literal existence of an all-female society, he recognized their symbolic value. Their supposed foundations of cities (Ephesus, Smyrna, Cyme, Themiscyra) and lingering cults of warrior goddesses fascinated Romans interested in antiquity and urban origins . Strabo’s reflections on the “barbarian” sharpened the divide between civilized Romans and dangerous outsiders:

“who could believe that an army of women, or a city, or a tribe, could ever be organized without men”

Strabo, Geography 12.8.7

Placed within Rome’s mapped horizons, these legends became part geography, part ideology. For Strabo, Rome’s conquest transformed savage peoples into civilized subjects; Amazons thus symbolized the inversion of order, against which Roman hegemony could define itself. His account reinforced Augustus’ message that Rome brought law, peace, and governance to the world.

Imperial Monuments and Civic Space

Augustan public art drew heavily on Amazonomachy motifs inherited from Greece, adapting them to new imperial contexts. Reliefs, statuary, and monumental programs cast Amazons as barbarian foils, their defeat visual shorthand for Rome’s triumph.

This visual language resonated with Augustan ideology: civilization conquering disorder, pietas overcoming hubris, and the restored Republic standing firm against threats. At the same time, public works after Actium incorporated nautical motifs—prows, tritons, and sea imagery—to commemorate Augustus’ naval victory.

Amazon battles, like depictions of Parthians kneeling before Mars Ultor, reinforced Rome’s dominance while masking the brutality of recent wars. They became visual proclamations of unity, placing Rome in continuity with Greek tradition yet elevating it to new universality.

Domestic Display and Personal Identity

Private commissions also embraced Amazon themes, reflecting both elite aspirations and broader cultural trends. Patrons like C. Sosius, once Antony’s supporter but reconciled to Augustus, employed Amazon imagery in monuments and domestic art to signal loyalty and Roman superiority .

Jewelry, gems, and mosaics circulated Amazon motifs in more intimate settings. These pieces drew on Greek allegories but were infused with Roman readings: Amazons as markers of foreignness, barbarity, and gender inversion, conquered or assimilated by Rome. Even in private homes, such imagery reinforced the ideology of Roman supremacy, showing how deeply embedded the Amazon symbol was in both public and personal spheres .

In Augustus’ forty-year reign, Amazon imagery became a tool for shaping Roman identity. Virgil’s Camilla dramatized the tension between admiration and suppression of outsiders; Strabo reinterpreted Amazon ethnography within a Roman imperial worldview; public art broadcast images of conquest and unity; and private art disseminated these themes into daily life.

Together, these depictions exemplify the adaptability of Amazon mythology. Borrowed from Greek tradition but repurposed for Rome’s needs, Amazons provided Augustus with a malleable figure through which to articulate victory, gender order, and imperial destiny. They embodied the foreign, the dangerous, and the admirable all at once—ideal foils for defining what it meant to be Roman.

The Julio-Claudian and Flavian Imagination

After Augustus’ long reign, the Julio-Claudian emperors inherited an empire that was vast, restless, and in constant contact with new frontiers. Campaigns in Britain, Mauretania, Armenia, and along the Rhine and Danube brought Rome face to face with peoples who, like the Amazons of old, seemed exotic and defiant.

Unlike Augustus’ carefully controlled propaganda, the imagery of this age was less cohesive. The Amazons were now reimagined as personifications of nature and religion—symbols of lands, cults, and peoples Rome sought to dominate or absorb.

Pliny the Elder: Natural History of the Amazons

Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, embedded Amazons within a catalogue of wonders from the empire’s edges. He approached them not only as mythic figures but as part of Rome’s broader ethnographic curiosity. To him, Amazons exemplified the strange and marvelous, positioned at the border between credible report and fabulous tale.

“They say that the Amazons dwell near the Caucasus, on the banks of the River Thermodon. They live without men, and only meet with them at certain times for the sake of children. The male offspring are either sent back to their fathers or destroyed, while the girls are reared and trained to war.”

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 6.19

Pliny’s descriptions reveal the Roman effort to classify the “other” in naturalistic terms, as though Amazons were another curiosity like exotic animals or distant rivers. By placing them alongside real peoples and natural marvels, Pliny gave the myth ethnographic weight, reflecting Rome’s ambition to encompass the whole world in its knowledge. Yet the Amazons remained liminal, blurring the line between nature’s oddities and human society.

Quintus Curtius Rufus: Alexander and the Amazon Queen

In the History of Alexander, Quintus Curtius Rufus retold the legendary meeting of Alexander with the Amazon queen Thalestris. Whether the encounter was historical or fabricated mattered little; what counted was its meaning in a Roman context.

“Thalestris, queen of the Amazons, came to Alexander with three hundred women of her nation, declaring that she wished to bear children from him worthy of their father. She remained with him for thirteen days, and then departed with her companions.”

Quintus Curtius Rufus, Histories of Alexander 6.5

The story allowed Curtius to explore themes of power, sexuality, and foreign allure. The queen’s attempt to mate with Alexander symbolized both admiration for his greatness and anxiety about female dominance.

For Romans reading under the Julio-Claudians, the tale resonated with recent memories of Cleopatra, another foreign queen who unsettled Roman order. Curtius thus used the Amazon myth as a safe mirror: a way to engage with anxieties about empire, women, and submission without naming contemporary politics too directly.

Amazons and the Divine

Amazons were deeply entangled with religion. Ancient tradition called them “daughters of Ares,” and their cult practices were linked with Artemis Tauropolos, Cybele, and other powerful female divinities. In Roman interpretation, this association deepened.

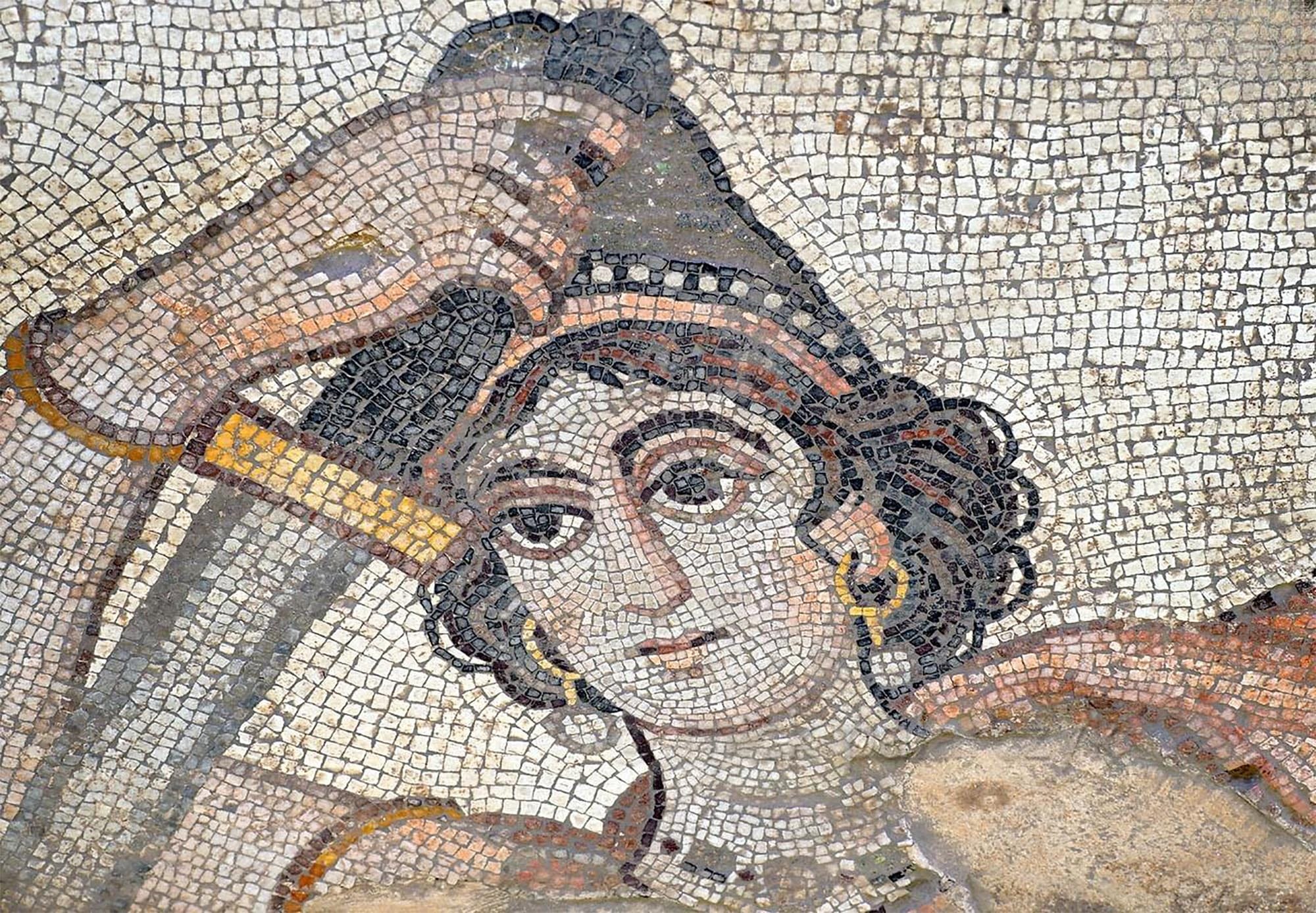

Art and literature emphasized Amazons as priestesses or attendants of gods, a link that underscored their liminality: they were female, martial, and divine. Roman coinage under emperors like Domitian depicted Amazons in connection with cities such as Ephesus or Smyrna, highlighting their role in civic religion. In these portrayals, Amazons stood for conquered cities or provinces, their martial traits softened into symbolic loyalty to Rome.

Monuments and Civic Identity

Monumental art under the Julio-Claudians and Flavians often deployed Amazons to personify captured peoples or subdued cities. Reliefs might show Roman soldiers overwhelming Amazonian figures, echoing earlier Greek Amazonomachies but now charged with imperial propaganda.

In civic space, the Amazon motif signaled victory and order, a visual shorthand for Rome’s ability to tame rebellion and bring stability. Where Augustus’ monuments had stressed unity and destiny, the Flavian use of Amazons underlined conquest, suppression, and the power of Rome to redefine outsiders as subjects.

Domestic Display and Cultural Blending

In domestic art—sarcophagi, gems, jewelry, lamps—Amazons continued to appear, but in more ambiguous forms. Some works depicted tragic scenes, such as Penthesilea’s defeat by Achilles, resonating with themes of noble defeat and cultural contact. Others portrayed Amazons as allegories of foreign lands, suitable for elites who wanted to show both their cosmopolitan outlook and their loyalty to Rome.

These private uses reveal a more hybrid cultural world. Roman identity was increasingly influenced by provincial traditions, and Amazon imagery absorbed this mixing. The figure of the Amazon could be both admired and pitied, feared and assimilated, reflecting the contradictions of a vast empire negotiating constant cultural exchange.

In the Julio-Claudian and Flavian periods, Amazons evolved from being foils for heroic Rome into more complex figures embodying nature, religion, and cultural hybridity. Pliny treated them as natural marvels; Curtius Rufus used them to reflect anxieties about empire and gender; artists and coin-makers transformed them into personifications of cities and conquered peoples.

The result was a more fluid Amazon—less a singular enemy, more a flexible symbol that could express conquest, assimilation, or religious devotion. This mirrored Rome’s own transitions: from Augustus’ unity after civil war to an empire marked by diversity, provincial encounters, and ongoing negotiations of identity.

Amazonian Echoes in the Era of Trajan and Hadrian

During the age of the Adoptive Emperors (96–180 CE), the Amazon myth did not disappear but gained new dimensions. With Rome secure under rulers like Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, Amazons became symbols of cultural memory and moral reflection, less about raw conquest and more about identity and commemoration.

Plutarch, writing in the Life of Theseus, emphasized how mythic encounters with the Amazons tested the very limits of civilization:

“When the Amazons invaded Attica, Theseus fought them in a great battle in the very heart of the city. The war was long and perilous, and only ended when a truce was agreed. This was the first time the Amazons had marched into Greece, and they proved themselves formidable opponents.”

For Plutarch, the Amazon episode was not frivolous legend but a serious meditation on governance, order, and the challenges posed by outsiders.

Arrian, in his Anabasis of Alexander, addressed the famous tale of Alexander’s meeting with the Amazon queen Thalestris only to reject it:

“As for the story that the Amazon queen came to Alexander, it is not credible. Aristobulus and Ptolemy, who were with him, make no mention of it, and it seems to me impossible that such an event could have occurred. Yet some writers delight in marvelous tales, and this is one of them.”

His skepticism shows both a historian’s concern for accuracy and a Roman unease with tales of female power on the imperial frontier.

Pausanias, in his Description of Greece, embedded the Amazons firmly in local memory and sacred topography:

“In Athens there are tombs of the Amazons, for they are said to have fought a great battle there against Theseus. Even now the Athenians show where the invaders camped, and where they fell. The Amazons are remembered not as mere myths, but as part of the city’s story.”

For Pausanias, Amazon legends lived on in shrines and monuments, tying myth to civic identity under Roman rule.

As aforementioned, in art and iconography, the focus shifted. Public monuments now celebrated real imperial victories—Trajan’s Column over the Dacians—so Amazons appeared more often in funerary and domestic contexts.

Sarcophagi depicted tragic Amazonomachies, such as Penthesilea’s defeat by Achilles, not as simple triumphs but as meditations on the violence and sorrow of war. Gems, reliefs, and household objects also carried Amazon imagery, sustaining their symbolic power in everyday life.

By this period, the Amazon was no longer just a barbarian foil. She had become a mirror of hybridity and moral questioning, embodying both noble opposition and tragic defeat.

Her continued presence in literature, art, and civic memory reflected Rome’s evolving sense of itself: confident in power yet aware of the complexities of identity, culture, and the costs of war. (The Empire's muse: Roman interpretations of the Amazons through literature and art, by Erin W. Leal)

In the end, the Amazons endured in Roman thought not because they were real, but because they were useful. They offered a canvas on which Romans projected fears and fascinations — of women who fought, of lands beyond their borders, of cultures unlike their own.

To look at the Amazons through Roman eyes is to see how myth could be endlessly reshaped, carrying forward the weight of Greek tradition while serving the needs of an empire that was always defining itself against an “other.” Their lasting presence in poetry, history, and art reminds us that the boundaries between history and imagination were never fixed, and that the figures of legend could wield as much power in shaping identity as any emperor or general.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: