Roman Mines as Environmental Catastrophes: How the Empire Polluted the Mediterranean with Lead

Rome’s silver and gold wealth carried an unseen price. Mining and smelting poured lead into the air and seas, leaving a chemical signature in the Mediterranean that scientists can still measure today.

The Mediterranean was not only a sea of trade and conquest. It also became the basin that absorbed the waste of an empire. New research analyzing seabed sediments in the Aegean has demonstrated how Roman mining and metallurgy introduced measurable levels of lead pollution beginning more than two thousand years ago. Around 2150 years before the present, a clear and persistent signal of lead appears across marine and terrestrial archives of the region. This coincides with Rome’s consolidation of power in Greece following the destruction of Corinth in 146 BCE.

Rome’s Expanding Footprint in the Mediterranean

The study emphasizes that this was not a localized phenomenon. The spread of lead contamination shows that human activity had become large enough to leave a basin-wide chemical footprint. Lead released during mining and smelting processes did not remain confined to the mines themselves but traveled through the atmosphere and rivers into the sea. Once deposited on the seabed, it preserved a record of imperial activity that remains visible to modern science.

This finding reframes the reach of Roman power. Roads, cities, and armies expanded the empire on land, but its industrial activity extended its influence into the natural environment. The onset of marine lead pollution marks one of the earliest examples of widespread human impact on the sea, centuries before the industrial age.

Mining, Coinage, and the Luxury Economy

At the heart of this pollution was the empire’s reliance on silver and gold. Roman coinage was the foundation of its fiscal system. Soldiers, officials, and merchants relied on a steady supply of silver denarii and gold aurei, and these coins required continuous mining and refining.

To extract silver, Romans used a process known as cupellation. Lead-bearing ores were heated until the base metal oxidized and separated, leaving behind the precious metal. This method, while effective, produced large quantities of airborne lead particles that could travel long distances.

The demand for coinage was immense. The empire’s expansion required armies to be paid and provincial administrations to be financed. Monetary reforms, such as those of Augustus and later emperors, depended on the steady production of refined silver and gold. Each new issue of coins represented not only a political statement but also a burst of metallurgical activity, with pollution as its by-product.

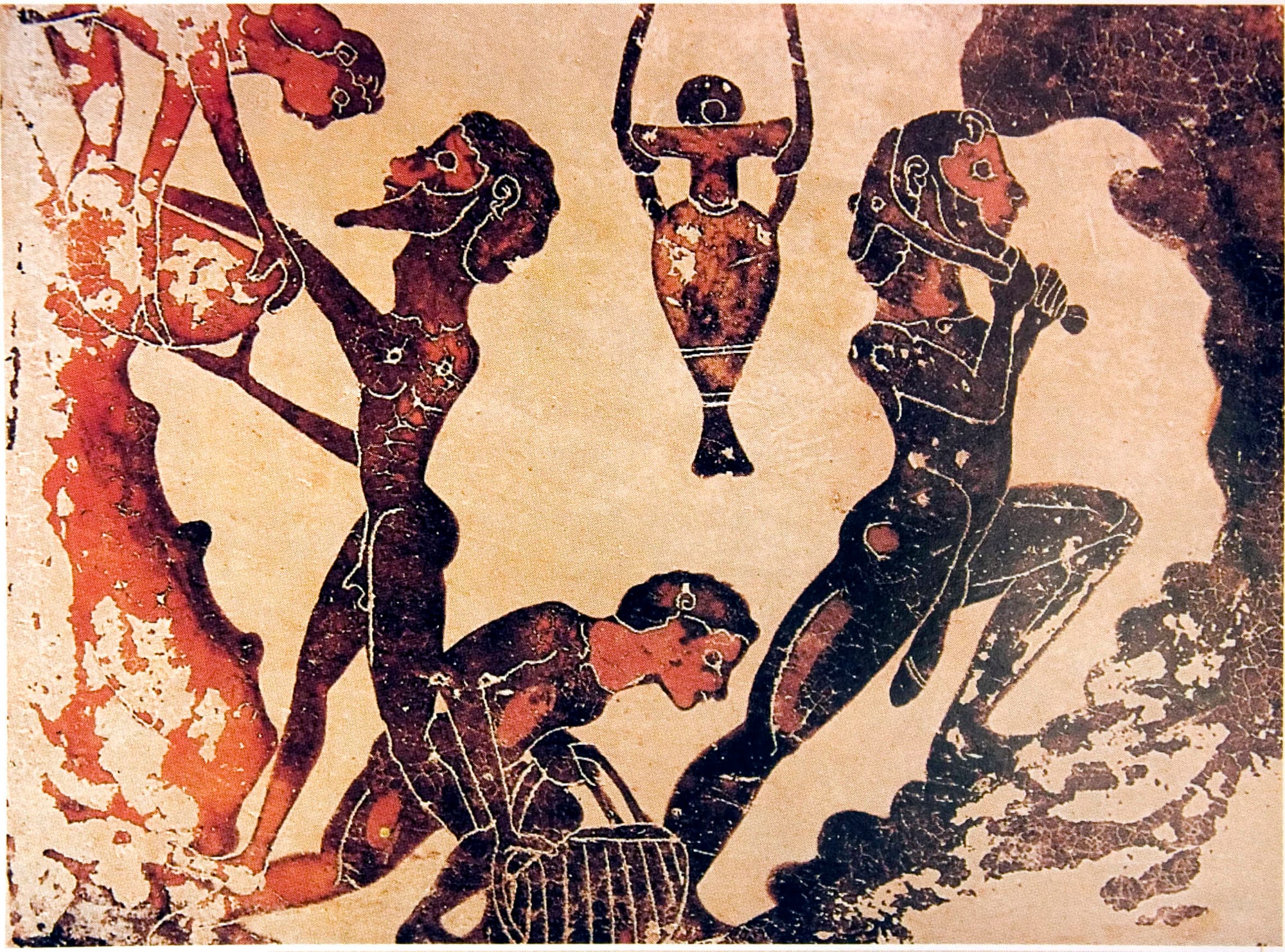

Silver and gold were also central to elite consumption. Wealthy Romans commissioned jewelry, tableware, and decorative objects that required additional refining and smelting. Public spectacles and temple dedications displayed metals on a grand scale. The cultural importance of silver and gold reinforced the economic demand, ensuring that mining districts continued to operate at high capacity.

The environmental cost of this demand can now be measured in marine sediments. The cores extracted from the Greek seas reveal sustained lead levels for a full millennium after their first appearance, showing how deeply the economy of empire was tied to continuous extraction and its ecological consequences. (The Metallurgy of Roman Silver Coinage, by Butcher & Ponting)

The Aegean Mining Landscape

The Aegean region contained several major mining centers that contributed to Rome’s wealth. The Laurion mines in Attica had been active since the Classical period and were famous for their extensive underground networks and slag heaps. These mines were crucial to the finances of Athens in the fifth century BCE and later came under Roman influence. Their galleries, washeries, and furnaces left a landscape visibly shaped by extraction.

Further north, the Pangaion mountain range and the island of Thasos were also rich in silver and lead ores. Archaeological surveys have documented shafts, smelting debris, and metallurgical installations that testify to large-scale production. These districts supplied not only local markets but also the wider Roman economy. The exploitation of such resources illustrates how Rome drew upon the mineral wealth of conquered territories to sustain its fiscal and cultural systems.

The environmental effects of these mines extended beyond the sites themselves. Deforestation to provide timber for supports and charcoal for furnaces altered local ecosystems. Erosion carried sediments and pollutants into rivers, which transported them to the coast. Combined with atmospheric emissions from smelting, these processes ensured that the impact of mining was felt far from its point of origin.

Marine cores from across the Aegean confirm that the lead produced in these districts entered the sea in significant quantities. The geographical spread of the signal shows that Roman mining was not an isolated or local affair but a regional industry with basin-wide effects. (Archaeometallurgical studies of Laurion, Thasos, and Pangaion)

Atmospheric and Marine Pathways of Pollution

Understanding how Roman mining left its mark on the Mediterranean requires attention to the processes by which lead traveled. Smelting and cupellation released fine particles into the air. These could be transported by prevailing winds across large distances before settling on land or water. The study describes this clearly: the release of lead was:

“predominantly via the fine-particle fraction and, as such subject to large-scale atmospheric transport, resulting in a supra-regional to hemisphere-wide distribution.”

Communications Earth & Environment, by Koutsodendris et al.

Rivers and streams carried another portion of the contamination. Mines and smelting sites produced waste products that weathered into waterways, especially where forests had been cleared. With reduced vegetation, soil erosion increased, and sediments enriched with lead entered the rivers. These, in turn, emptied into the sea, where they contributed to the accumulation of pollutants in coastal and marine environments.

The combination of these pathways explains the strength and persistence of the signal in Aegean sediments. It also shows how tightly connected ancient societies and natural systems were. Mines, forests, rivers, and seas formed a single network of cause and effect, with human demand for metals driving changes across the landscape and into the marine realm. The fact that this impact can still be measured today demonstrates how durable such processes were.

Rome’s Environmental Legacy

The continuity of lead pollution for over a thousand years underscores how deeply the empire’s economy depended on mining. Peaks in lead levels align with periods of political stability and economic growth, while temporary declines correspond to times of disruption. The overall picture is one of sustained pressure on the environment, tied directly to the structures of Roman society.

What is striking is the persistence of these signals in the present. The cores analyzed in the Aegean show that lead levels remain above natural background conditions, even after the end of antiquity. The Roman and Byzantine centuries created a long-lasting chemical horizon that has not been erased. While later industrial activities added their own pollutants, the ancient contribution remains identifiable.

This continuity highlights how human impact on the environment is not only a modern phenomenon. The Roman Empire, often admired for its engineering and administration, also demonstrates how pre-industrial societies could alter ecosystems on a regional scale. The Mediterranean, a central arena of Roman activity, preserves this legacy in its very sediments.

Reading Rome in the Seabed

The Roman Empire’s mining operations were more than a matter of economic policy or elite display. They were engines of environmental change whose effects can still be traced today. By demanding continuous supplies of silver and gold for coinage, jewelry, and public spectacle, Rome ensured that mines and furnaces worked without pause. The lead they released entered the atmosphere and rivers, eventually finding its way into the sea.

Marine sediments now provide the archive of this activity. They record the onset of pollution in the second century BCE, its persistence for over a millennium, and its continued presence above natural levels. Rome’s conquest and economy extended its influence into the natural world, leaving a chemical signature alongside its monuments and texts.

To study these sediments is to read another history of empire, one not written in stone but in dust and deposits. It shows that the environmental consequences of human ambition began long before industrialization, and that the seas still carry the imprint of Rome’s search for wealth. (Communications Earth & Environment, by Koutsodendris et al.)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: