Polybius and the Architecture of Roman Power

A hostage in Rome, yet a historian of freedom—Polybius interpreted the Republic not just as a Greek admirer, but as a thinker who mapped its power, structure, and fate with piercing clarity.

A Greek by birth, a soldier by training, and a historian by conviction. Polybius of Megalopolis stood at the crossroads of two worlds—his native Hellenistic Greece and the ascendant Roman Republic. As a hostage in Rome during the 2nd century BCE, he gained a front-row seat to the machinery of Roman power, observing its military triumphs, political structures, and imperial ambitions.

Rather than mourn the fall of Greek independence, he set out to understand the forces that had tilted the balance of history—and in doing so, wrote one of antiquity’s most remarkable works: The Histories. What began as a record of Rome’s rise became a meditation on fate, governance, and the endurance of great states.

For a closer look at Polybius’s early life and his personal ties to Rome’s elite, see our earlier article:

Polybios the Historian: Method, Reach, and Authority

He was not content to merely report what happened; he wanted to know why it happened. As a methodological heir to Thucydides and a critical reader of earlier historians, he set new standards for accuracy, verification, and interpretation.

He traveled widely to observe events and geography firsthand—from Spain to Alexandria. Yet he was also critical, wrestling with his predecessors in what Strabo later described as the manner of Cercyon—leaving a powerful imprint on those who followed.

He likened the ideal historian to Odysseus, compelled to journey, examine, and endure. That spirit guided him through his authorship of The Histories, which originally spanned forty books and chronicled Rome’s ascent to Mediterranean dominance from 264 to 146 BCE. Only Books 1–5 survive in full, with later ones fragmentary—but they remain central to any serious study of ancient historiography.

Polybius did not write history with brevity in mind. His Histories, though framed around just over fifty years of Roman expansion, swell far beyond the political narrative to include philosophical reflections, ethnographic notes, and methodological treatises.

Three full books are digressions—on Roman government (Book 6), historiography (Book 12), and geography (Book 34)—but many more passages wander into side topics: the fermentation of jujube wine, the décor of Alexandrian courtesans' homes, the dances of Arcadian youth. Often, he ends such digressions by explaining why he included them—and then stating that the digression is over.

This expansiveness, a marked contrast to the disciplined reserve of Thucydides, helped shape his reputation as a self-conscious and deeply reflective historian.

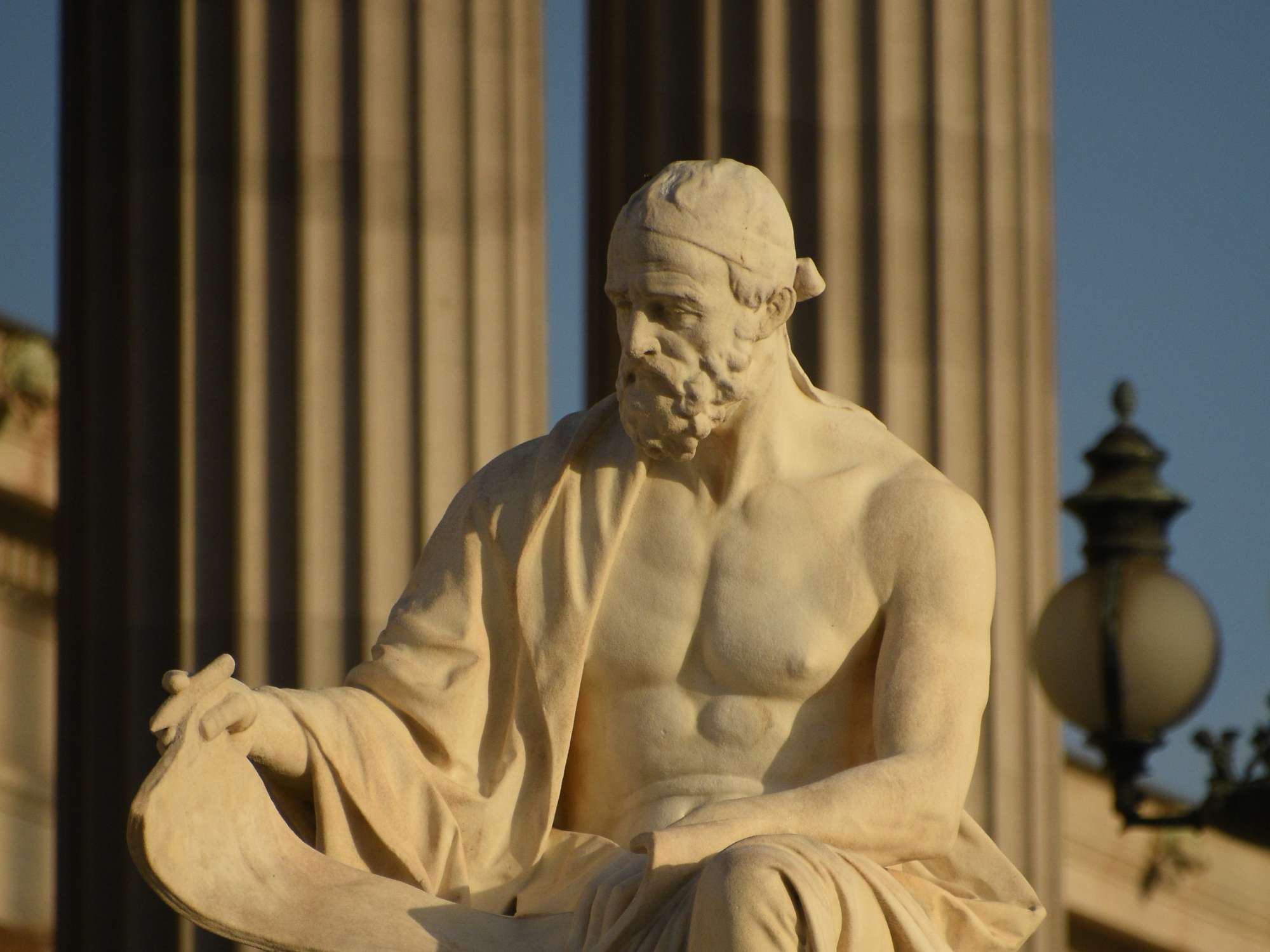

Statue of Historian Polybius, at the Austrian Parliament. Credits: Amaury Laporte, CC BY 2.0

He openly debated how a historian should write about events in which he participated, whether he should use first or third person, and how interviews should be conducted and interpreted. For Polybius, even the act of questioning could reshape the past. He writes that without active engagement, an interviewer “is, though present in a certain sense, not present”.

“For how is it possible to examine a person properly about a battle, a siege, or a sea‑fight, … since the suggestions of the person who follows the narrative guide the memory of the narrator to each incident, and these are matters in which a man of no experience is neither competent to question … nor when present himself to understand what is going on; but even if present he is, though present in a certain sense, not present.”

Histories, Book 12

This metahistorical gaze permeates the Histories. He constructs a layered field of perception—readers observe commanders who themselves are observers, interpreting terrain, public mood, and enemy intent. The audience becomes a kind of distant spectator in a Roman arena, analyzing events as combatants do. Vision is power, and interpretation becomes action.

But this recursive structure also has a paradoxical effect. As generals anticipate perceptions and maneuver accordingly, war becomes stylized performance. History itself begins to resemble theater: filled with feints, second-guessing, and spectacle. He describes the sack of cities not just in military terms but as “shock therapy”, carried out for effect.

Strategic decisions hinge on prevailing assumptions—one Roman general targets a supposedly impregnable city first to terrify others. Thus, for all his practicality, his account of action becomes a study in perception. Πράξεις (actions) become μεταπράξεις (reflections on action), and the narrative becomes a commentary on the gaze itself.

His history is not just about politics, war, and constitutions—it is also about how power is seen, interpreted, and performed. In this, Polybius offers not only a handbook for statesmen, but a mirror for historians themselves.

The Constitution that Withstood Time: Book 6 and the Theory of Cycles

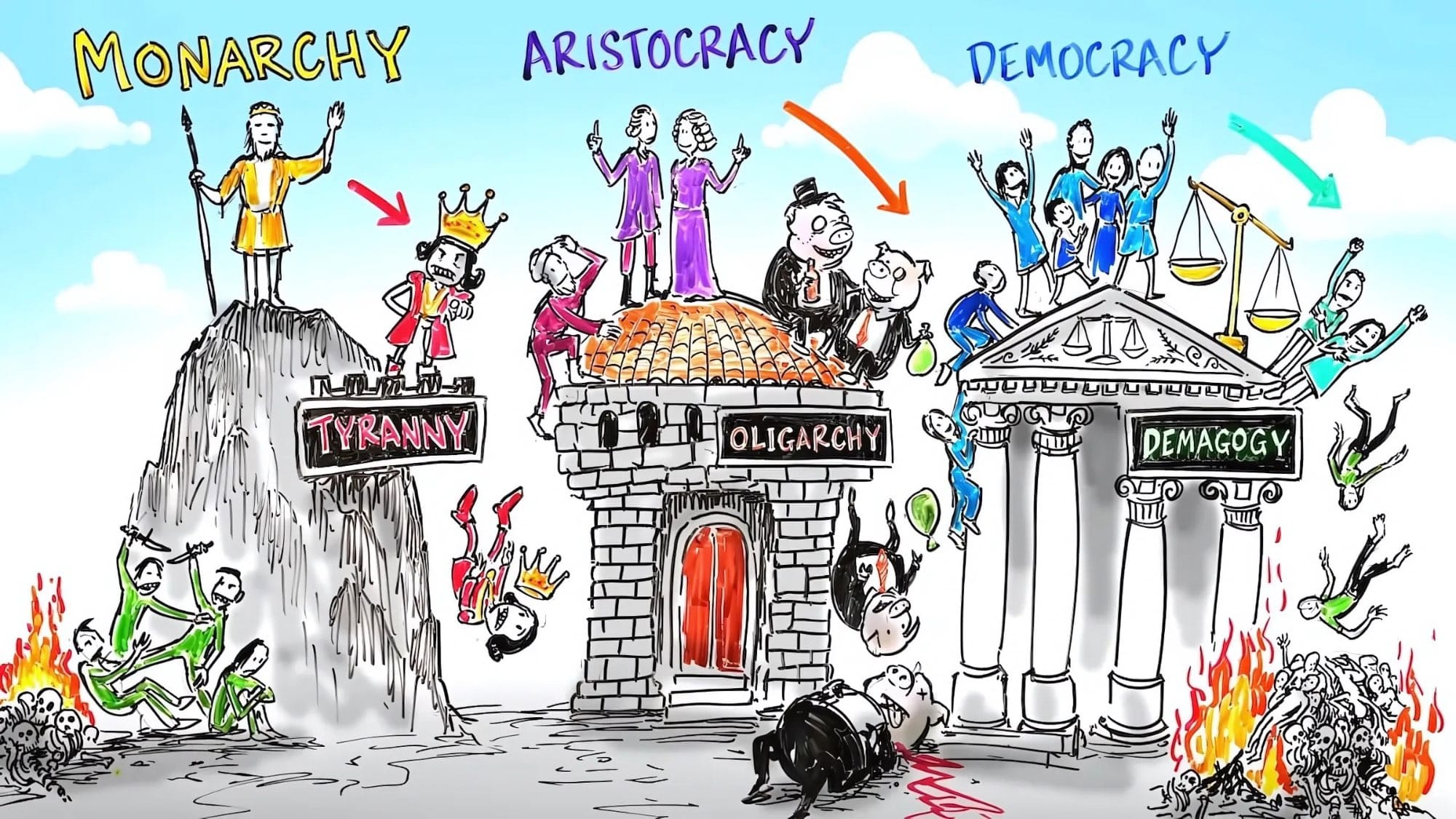

In Book 6, he offered a model that shaped Western political thought for centuries. Drawing from Plato and Aristotle, he introduced the concept of anakuklosis (ἀνακύκλωσις), the cyclical degeneration of political systems: monarchy to tyranny, aristocracy to oligarchy, democracy to mob rule.

But Rome, he argued, had temporarily escaped this cycle through a mixed constitution—blending monarchy (the consuls), aristocracy (the Senate), and democracy (the popular assemblies):

"Each element was watched and held in check by the others."

This structure, he believed, granted Rome its unique resilience and meteoric rise. Later thinkers, from Cicero and Machiavelli to Montesquieu, cited him as the originator of checks and balances—a legacy embedded in modern constitutional design:

"That threefold commonwealth... when held in moderation, seemed to be the most stable kind of state."

Cicero, De Re Publica, 1.69

"And among these systems, the one that Rome maintained was without doubt the best, as Polybius testifies."

Machiavelli, Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio, I.2

A Greek Explains Rome: Cultural Transmission and Literary Influence

Key ideas such as Fortuna (τύχη), moral exempla, and civic responsibility passed into Roman literature via Polybius’s work. His ideal of the ἀνήρ πρακτικός—a man of action and experience—became a Roman historical archetype.

Yet he was not inventing these ideas alone; he was a conduit through which Greek intellectual habits were absorbed and reinterpreted by the Roman world.

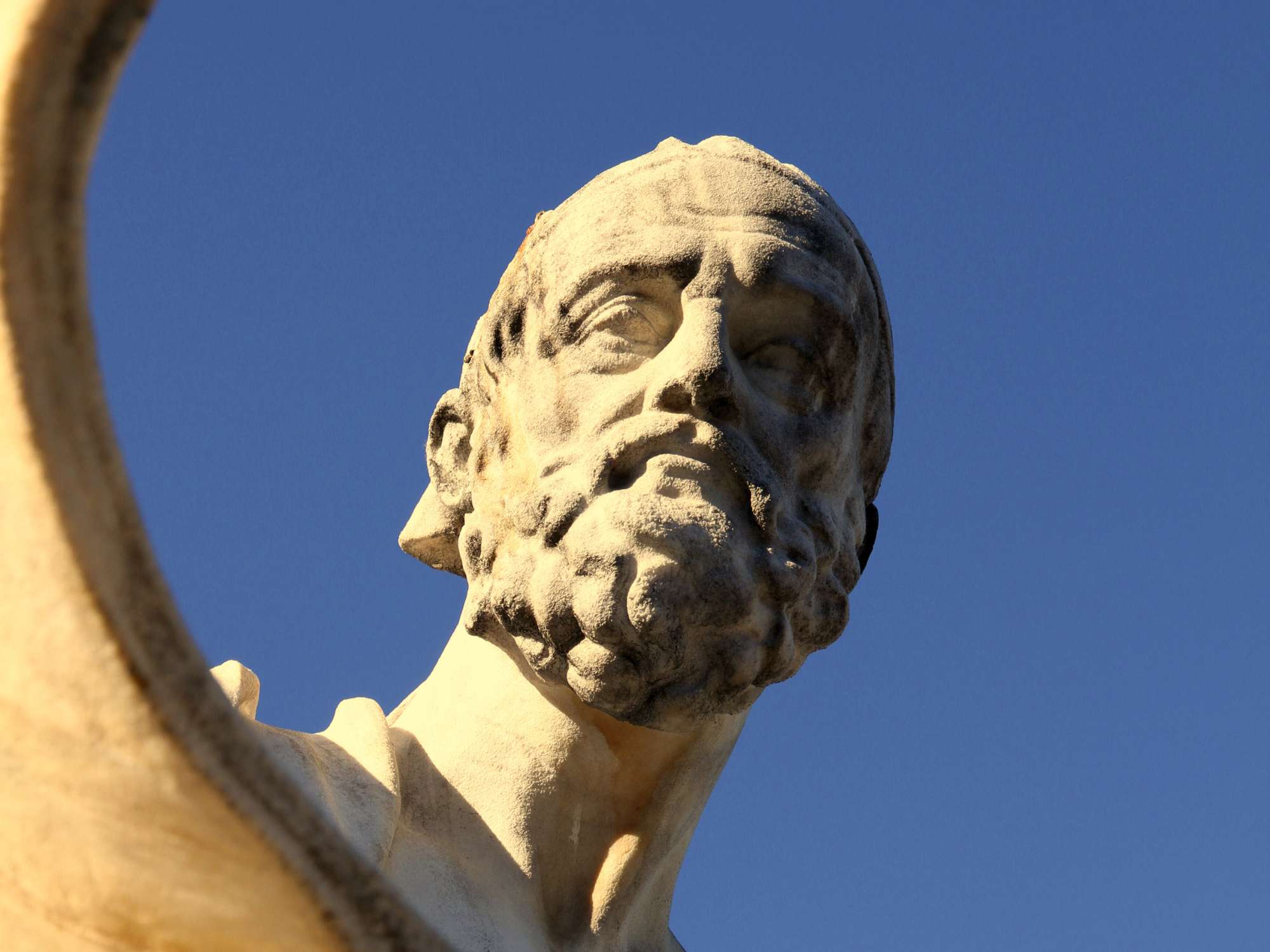

Close up of the statue of Polybius in front of the Parliament building in Vienna. Credits: BrendanHunter from Getty Images Signature, by Canva

Arcadian Blood and Roman Myth: Evander and the Shared Past

One of the most original contributions in his narrative is the invocation of shared mythological heritage. He embraced the Roman belief that their founders were Arcadians led by Evander, son of the nymph Carmentis.

Evander named the Palatine Hill and introduced Greek rites, which Romans preserved as ritus graecus. He pointed to linguistic similarities and early Latin inscriptions to reinforce this cultural bridge. His own origin from Megalopolis, in Arcadia, likely played a role in lobbying for his stay in Rome—Evander was not just myth but politics.

These mythological ties blurred lines between conqueror and captive. They symbolized the fusion that he, himself embodied: Greek intellect in Roman service, Greek memory in Roman ambition.

The Historian as Mediator: Legitimizing and Questioning Empire

Polybius’s role was not merely to chronicle but to mediate—between past and future, Greece and Rome, admiration and analysis. He justified Roman actions as reasonable responses to instability, casting imperialism as a stabilizing force. This allowed him to maintain favor among Roman elites while educating Greek audiences about the nature of power.

But his tone shifts after 146 BCE, following the sack of Corinth and the fall of the Achaean League. His silence on these events hints at internal conflict. He does not fully defend Rome, nor does he condemn it outright. He interprets, explains, and sometimes rationalizes—a stance that made him both controversial and enduring. (Polybius and Rome’s Eastern Policy, by F. W. Walbank)

A Method for Judging Power: Truth, Usefulness, and Instruction

Polybius stands apart from many of his predecessors for his insistence that history must serve a public function. He rejected the notion that aesthetic charm or rhetorical polish could ever substitute for factual integrity.

In his view, history was to be judged not by its beauty, but by its truthfulness and its capacity to instruct. Historians who shaped narratives simply to dazzle or entertain were abandoning their responsibility. He condemned the use of invented speeches and decorative language, arguing that only those present at events—or those who consulted reliable witnesses—should attempt to reproduce dialogue at all.

“No further criticism of such writers is necessary. They rank in authority, it seems to me, not with history, but with the common gossip of a barber’s shop.”

Histories, Book 12

He uses this sharp line to highlight his belief that accuracy, autopsy (eyewitness experience), and reliable testimony are the cornerstones of true historical writing.

Invented speeches, in his view, had no place in serious historiography.

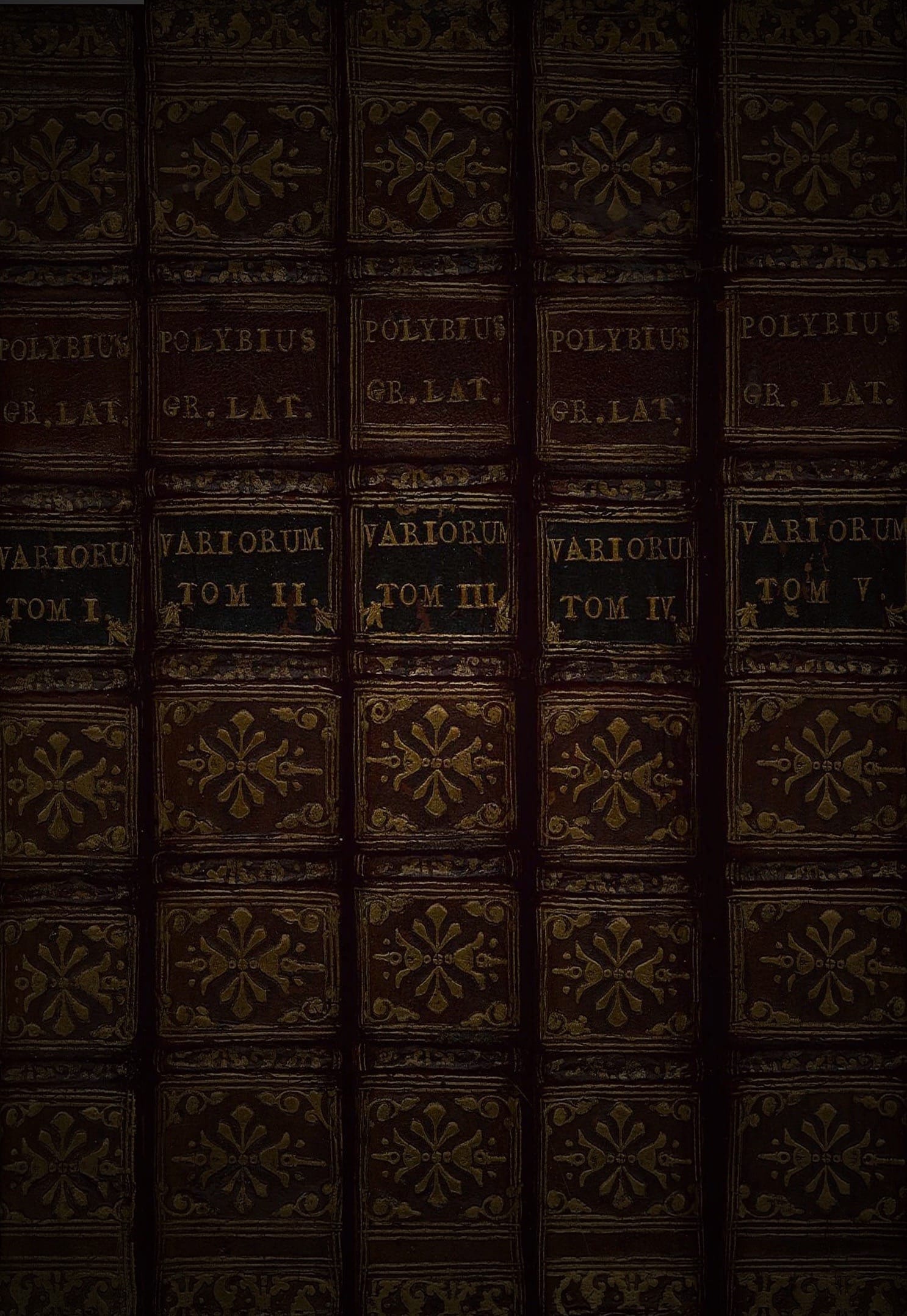

The complete 5 books of Polybius’s Histories. Credits: The Wolf Law Library, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This emphasis on utility and accuracy ran through every part of his method. History, to Polybius, was a practical tool, not a literary diversion. Its purpose was to train citizens and leaders in how to recognize patterns, assess causes, and act wisely. He viewed his work as a manual for navigating political life, not as an anthology of edifying tales or cultural memory.

His distinction between τέρψις (delight) and ὠφέλεια (benefit) shows where he placed value: literature may please, but history must teach. He uses this distinction to emphasize that the goal of historiography is not τέρψις (entertainment or rhetorical pleasure), but ὠφέλεια (moral and practical instruction). This reflects his broader view that history should educate, not merely please.

What distinguished Polybius further was his acute awareness of the historian’s own presence in the craft. He did not simply gather facts; he analyzed the process of gathering them.

He asked what it meant to observe, to question, and to narrate truthfully. In his view, even the act of interviewing required discernment and judgment: a passive listener might be physically present, but “though present in a certain sense, not present” at all in the critical work of interpretation.

The historian’s job, therefore, was not just to record but to interrogate, compare, and synthesize. In this way, Polybius approached what modern thinkers would call metahistory—an understanding that the writing of history itself shapes what is remembered, and how.

He exposed the artificiality of rhetorical embellishment in historical prose and critiqued other historians who lacked either personal experience or methodological rigor. He believed that good history demanded not just intelligence but preparation, industry, and purpose. He saw the historian’s role as no less demanding than that of a general or statesman.

Ultimately, he offered his readers not just a record of Rome’s rise but a framework for how to write—and read—history responsibly. He laid bare the mechanics of political power and historical narrative alike, instructing not only by example but through reflection on the very process of instruction. His history was nut merely a description of the world as it was, but a guide for what it could become—if studied with care, and understood with purpose. (Polybius and the Legacy of Fourth-Century Greek Historiography, by John Marincola)

From Cycle to Revolution: Polybius Anacyclosis and the Language of Political Change

In his Book 6, with its famous theory of ἀνακύκλωσις—the cyclical degeneration and renewal of political constitutions—held a pivotal place in early modern political thought. Yet it was not just the content of his theory that endured; it was the way it was translated, interpreted, and embedded into new ideological frameworks that shaped the history of ideas.

By tracing the evolution of how he was rendered in early English, French, and Latin translations, one can observe how the very word “revolution” was born not only as a mechanical or astronomical concept but as a political metaphor drawn from his constitutional cycle. Originally, he described a fixed pattern of political evolution: monarchy declines into tyranny, aristocracy into oligarchy, democracy into ochlocracy or mob rule, before the cycle begins anew.

“The first constitution to arise is monarchy.

This changes into its vicious form, tyranny.

Then comes aristocracy, which degenerates into oligarchy.

Finally, the people set up a democracy, which in turn lapses into mob rule (ochlocracy).

And then, out of mob rule, monarchy once more emerges, as a kind of savior from chaos—and so the cycle begins anew.”

Polybius Histories, 6.9–10, paraphrased translation based on the Loeb edition

Each system contains the seeds of its own decay. But translators of Polybius—especially during the 16th to 18th centuries—began to use the term revolution to describe these transitions, not merely as repetitions of failure but as potential instruments of renewal and justice. The Greek anakyklōsis (ἀνακύκλωσις), which simply meant a turning again or recurrence, was increasingly rendered as révolution in French and revolution in English, especially in editions that came after Machiavelli and Montaigne had popularized Roman constitutional thought.

This subtle change in terminology bore deep consequences. Instead of seeing constitutional shifts as unfortunate inevitabilities, some early modern thinkers began to regard them as moments of rupture with the past—openings through which liberty could be restored or tyranny overthrown.

Polybius's mixed constitution, once admired as a temporary escape from the cycle, now became an ideal toward which societies might aim by revolutionary means. The ancient cycles were being reconceived not as fate, but as a call to arms. More than just a semantic curiosity, this linguistic evolution marked a shift in the conceptual history of the West.

Is Every Civilization Doomed to Fail? - Gregory Aldrete

By the time of the Enlightenment, revolution had become a normative political goal. His theory, once a warning about the fragility of constitutions, now underwrote the very logic of their overthrow and re-foundation. When Montesquieu referenced him in his Spirit of the Laws, he too adopted the term revolution, thereby placing the ancient historian in a lineage that led to the American and French Revolutions.

The cycle was now understood not merely as natural law but as historical opportunity. In this way, Polybius's Book 6 was reborn in the early modern imagination—not only as a template of balanced governance but as a cipher for revolutionary change.

The republic he admired for its equilibrium became a reference point for those who sought to rebuild or reclaim political liberty. The rotation of power, once the domain of fate and Fortune (τύχη), was transformed into a human endeavor—intentional, moral, and often violent. In this transformation, the political language of the West forever changed. (A ‘Revolution’ in Political Thought: Translations of Polybius Book 6 and the Conceptual History of Revolution, by Dan Edelstein in Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 83, No. 1, 2022)

Polybius’s Histories offer more than a chronicle—they offer a theory of history as a civic tool. He wrote not to entertain, but to equip statesmen and citizens with models of action, judgment, and restraint. From his unique vantage point as a participant-observer, his work continues to inform how we understand the architecture of empire, the fragility of power, and the enduring need for balance in governance.

“For who is so lightweight or lackadaisical, that he would not wish to know how and with what species of government the Romans managed to get nearly the entire inhabited world at their feet, subjected to their sole rule, in less than fifty-three years?”

Polybius, Histories, 1.1

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: