Ingenious Warmth: How Romans Heat their Baths with the Hypocaust System

The Romans heated the water in their baths using a hypocaust system, which circulated hot air from a furnace beneath the floors and through the walls.

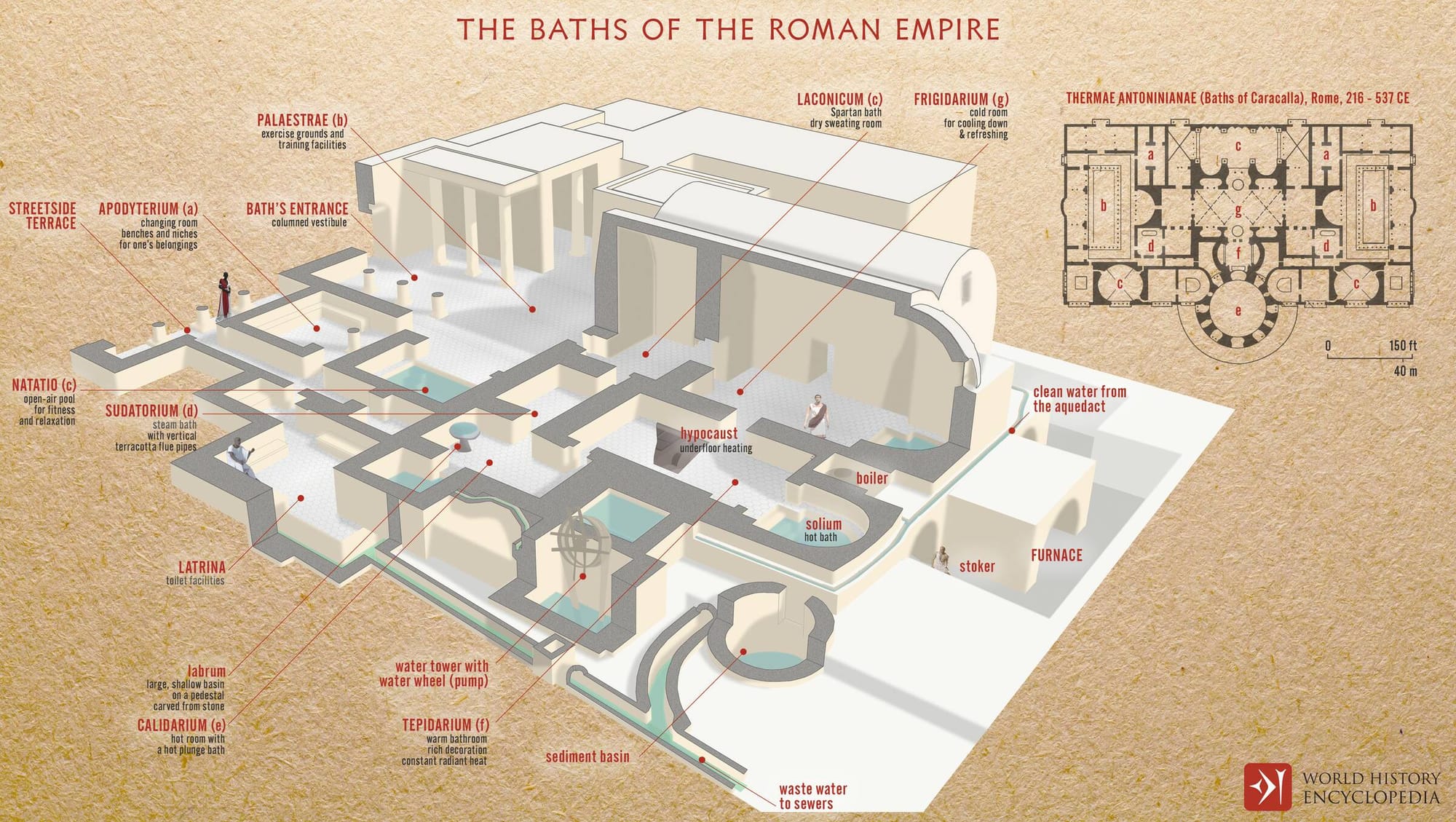

Roman baths, also known as thermae or balnea, were public bathing facilities in ancient Rome and throughout the Roman Empire. Public bathing was a central aspect of Roman culture and a significant part of daily life in Rome. The baths were much more than just bathing facilities. It was where the Romans went to clean themselves, socialize and even heal.

What is the history behind Roman baths?

Early Romans washed their arms and legs daily, which were dirty from work, but only bathed their entire bodies every nine days. They also swam in the Tiber River. Occasionally, some would take hot baths in the lavatrina, a room adjacent to the kitchen. As the custom of daily hot baths became popular, Romans began constructing bathrooms (balnea) in their homes. The first public bathhouses were built in the 2nd century B.C. By 33 B.C., there were 170 small baths in Rome, and by the early 5th century, that number had increased to 856.

Notable examples include the Roman baths of Bath and the Ravenglass Roman Bath House in England, as well as the Baths of Caracalla, Diocletian, Titus, and Trajan in Rome. Additionally, significant baths can be found in Sofia, Serdica, and Varna. Some of the most well-preserved baths are the various public and private baths in Pompeii and nearby areas.

Baths in the Roman Empire were supplied with water by the extensive aqueduct systems constructed by the Romans. Public bathhouses typically had priority over private users for water supply. Smaller baths or those in arid regions could operate with minimal water, storing it in reservoirs and cisterns.

In contrast, baths in areas with abundant water used generous supplies from the aqueducts to maintain elaborate features like fountains and cascades. By Trajan's reign (around AD 100), nine aqueducts supplied Rome with approximately one million cubic meters of water daily, about 300 gallons per person per day. Rome did not achieve such an impressive water supply again until modern times.

Romans were known for their advanced engineering skills, which they applied to various aspects of daily life, including heating their baths. Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of numerous Roman bathing complexes, and according to the Roman Regionary Catalogues, Rome had 856 registered bathhouses by the 4th century AD.

The Roman baths are known by several names. There is scholarly debate on whether "balnea," derived from the Greek word βαλανεῖον meaning "bath," or "thermae," from the Greek word θερμός meaning "hot," was more commonly used in Republican Rome.

One prominent theory suggests that Sergius Orata, a Greek, was responsible for the development of the baths, and it was only after Rome conquered Magna Graecia that the Romans incorporated baths into their society. This theory was widely accepted until archaeological discoveries at other bath sites complicated the Greek-origin hypothesis.

The primary issue with this theory is the presence of the hypocaust system in the Stabian Baths, which were likely built in the 1st century BCE under Sulla, before much of Magna Graecia was conquered by the Romans. While there is ample evidence suggesting that the Romans may have absorbed the earlier Greek model, the hypocausts in the Stabian Baths indicate that the reverse might have occurred.

Another possibility is that the Romans took over and improved existing Greek bath sites, leading to the presence of hypocausts at Greek bath locations. This pattern of borrowing and enhancing architecture is common in Roman history. However, closer examination of the Stabian Baths, especially the discrepancies in construction materials in the gates, suggests that this might not be the case, at least for that particular site. (The History and Importance of the Roman Bath by Haley Mowdy)

The hypocausts system of the Roman baths

The hypocaust was an ancient Roman heating system that provided underfloor heating and was invented at the end of the 2nd century BC. Although earlier models show evidence of floor heating systems, it appears that the Romans truly developed and perfected this technology. It consisted of a raised floor supported by pillars, called pilae stacks, creating a hollow space underneath.

A hypocaust (Latin: hypocaustum) is a central heating system in a building that generates and circulates hot air beneath the floor of a room and can also heat the walls through a network of pipes carrying the hot air. This system can extend to warm the upper floors as well. The term originates from the Ancient Greek words "hypo," meaning "under," and "caust," meaning "burnt" (as in caustic).

Hypocausts were employed to heat hot baths and other public buildings in ancient Rome, as well as in private homes. The wealthier merchant class considered them essential for their villas across the Roman Empire. Ruins of Roman hypocausts have been discovered throughout Europe, including Italy, England, Spain, France, Switzerland, and Germany, as well as in Africa.

Underneath the floors of the sauna and caldarium, a 2-foot deep air cavity circulated hot air from a furnace beneath the floor tiles, heating the space from below. To improve the distribution of hot air, the cavity floor was sloped upwards from the furnace, allowing the cooled air to flow back into the furnace more efficiently.

This suspended floor was supported by short, sturdy pillars called pilae, made from standard 8-inch square bricks.

Credits: JossK, Getty Images by Canva

Flues, known as caliducts, were installed in the walls to draw air from the hypocaust and release it through the height of the structure. This served two key purposes. First, circulating hot air through the caliducts allowed heat to accumulate in the thick stone walls as well as the floor, enhancing the overall climate of the space and the comfort of the bathers. Second, and perhaps most importantly, the caliducts helped to move toxic gases from beneath the floor up and out of the building.

Structural elements of the caldarium were specifically designed to respond to the warmth generated by the hypocaust system. Hot rooms often featured double-height vaults to allow steam and humidity to circulate throughout the building, preventing the wooden roof members from rotting.

Furnaces were typically located on the building's perimeter, enabling attendants to easily access them, as they required constant monitoring. The fires were fueled by small twigs and branches because larger logs burned too slowly to produce the necessary heat, which demanded significant manpower. Additionally, workers needed to regularly clean out ash and soot from the furnace to prevent the fire from being smothered and to avoid safety hazards.

It is evident that the Romans were burning a lot of wood, and research has shown that for one bath the consumption was approximately 114 tons of wood per year. That is why Romans were using solar power to assist the hypocaust system.

Roman Bath 3D model, Credits: Mikaël Sévère

Complementing the hypocaust was passive solar heating, a technique widely used by the Greeks with their winter rooms but perfected by the Ancient Romans. Passive solar can be described as "the use of natural processes, such as radiation, conduction, and convection, to distribute thermal heat provided by the sun," and it was a critical aspect of the success of the baths.

The hot rooms were positioned along the southwest-facing wall and featured large, glazed windows to allow maximum sunlight into the building. Since bathing activities typically occurred from midday to evening, this southwest orientation was crucial. Sunlight would enter through the windows and strike the thick stone floors, which served as the thermal mass. The stone would then reradiate the sunlight as heat, slowly warming the air upwards.

To enhance efficiency, Vitruvius described using a large bronze disk suspended from the ceiling to help regulate temperatures and reflect the radiation back to the pools. The bronze disk could be lowered or raised depending on the desired temperatures.

"The sun alone on sunny days could provide most of the energy to maintain the 100˚F temperatures. Indeed, even with fires reduced on sunny days, there would probably be some thermal energy [from the sun] stored in the doors and walls that would maintain the temperature as the sun [went] down.

On days where the sun [was] obscured by clouds, the hypocaust with reduced fire, or turned on only part of the time, could by itself easily maintain the temperature [100˚F inside] even with the temperature at 30˚F [outside]."

Windows, Baths, and Solar Energy in The Roman Empire. James W. Ring

A scholar back in 1956 said that: "the principles of radiant heating ... made the open rooms possible and, to date, we have not matched them in a modern building."

The art of passive solar design extends to both heating and cooling. To lower temperatures, the sun can be intentionally blocked. One method involved planting umbrella pine trees in the gardens surrounding the baths. On a hot sunny afternoon, after a long day’s work, people could find relief under these trees, whose canopies provided much-needed shade—sometimes the simplest solutions are the most effective.

This concept also applied to the structure itself. The large, cavernous spaces in the bathing complex allowed heat to rise above the occupants, while thick concrete and brick walls insulated against the outside heat. During the height of summer, the baths served as a refuge from the sun.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: