How Roman Pandemics and Plagues Allowed Ecosystems to Recover from Pollution

The Roman Empire’s great plagues reshaped not only society but also nature. New science shows that during times of crisis, pollution levels dropped and the Mediterranean briefly healed.

The Roman Empire is often remembered for its architecture, roads, and laws, but it also left an environmental legacy. Recent studies of marine sediments in the Aegean have shown how the empire’s mining and smelting released lead into the atmosphere and seas on a scale large enough to leave a detectable chemical signal. Around 2,150 years ago, coinciding with Roman expansion into Greece, this pollution first became visible in natural archives.

The Scale of Roman Pollution

The demand for silver and gold drove this contamination. Coinage, jewelry, and elite display all required refined metals, and the process of cupellation used to separate silver from lead ores released fine lead particles into the air. These could travel across the Mediterranean and settle in marine environments, where they became trapped in sediments. Over time, the seabed accumulated a layered record of Roman economic activity.

This record shows continuous pollution for more than a thousand years. Yet it also reveals sudden interruptions. During major pandemics that devastated the empire, lead levels in sediments fell dramatically. These declines provide evidence that plagues disrupted not only social and political life but also the environmental pressure created by Rome’s industrial economy.

The Antonine Plague

The first major pandemic recorded in Roman history was the Antonine Plague, which struck in 165 CE during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Likely carried by soldiers returning from campaigns in the Near East, it spread rapidly through the empire. Ancient physician Galen described its symptoms in detail, and modern scholars believe it was probably smallpox. Estimates suggest it killed between five and ten million people, weakening the empire’s military capacity and straining its resources.

Mining operations were highly dependent on labor. Enslaved workers, convicts, and free laborers were needed to dig shafts, transport ore, and operate furnaces. The Antonine Plague caused a sharp reduction in available manpower. The workforce required to sustain mining and smelting simply could not be maintained at previous levels. This reduction in labor had a direct impact on the amount of lead being released into the environment.

Economic disruption compounded this effect. With trade diminished and communities focused on survival, demand for new coinage and luxury goods fell. Refining activity slowed as markets contracted. The decline in both labor and demand meant that many mining operations either ceased or worked at reduced capacity. The environmental consequence is visible in the marine record: sediment cores show a clear reduction in lead levels dating to this period.

The Antonine Plague demonstrates how human health and environmental impact were directly linked. A disease that reshaped the empire’s society and economy also allowed ecosystems to recover, at least temporarily, from the pressures of extraction and smelting.

The Plague of Cyprian

A century later, the empire faced another devastating outbreak known as the Plague of Cyprian. Beginning around 249 CE, this pandemic lasted nearly two decades and struck during a time of political instability and external pressure. The bishop Cyprian of Carthage described its effects in his writings, noting high mortality and widespread fear. Some scholars suggest it may have been caused by a viral hemorrhagic fever.

The long duration of the Plague of Cyprian made its impact particularly severe. Cities lost large portions of their populations, and rural areas were also deeply affected. The crisis overlapped with the “Crisis of the Third Century,” when the empire faced invasions, economic collapse, and frequent changes of leadership. Mining and metallurgy, already vulnerable to instability, were heavily disrupted.

With reduced demand for coinage and diminished state capacity to organize large-scale operations, smelting slowed across the empire. While the environmental evidence for this period is less dramatic than for the Antonine or Justinianic plagues, it is consistent with a broader pattern of decreased pollution during times of widespread disease. The Plague of Cyprian thus represents another moment when the empire’s environmental impact was softened by demographic catastrophe.

This plague highlights how sustained crises could alter not only human systems but also the natural world. The combination of disease, political turmoil, and economic weakness temporarily reduced the empire’s pressure on ecosystems, even if recovery was uneven and short-lived.

The Justinianic Plague

The most devastating pandemic of antiquity was the Justinianic Plague, which began in 541 CE under the reign of Emperor Justinian I. Spread by fleas carried by black rats, it is recognized as an early outbreak of bubonic plague. Contemporary historian Procopius wrote vividly about its impact on Constantinople, describing thousands of deaths each day. Estimates suggest the pandemic killed as much as half the population in some regions.

The economic consequences were catastrophic. Agriculture declined, trade faltered, and state revenues plummeted. Mining, which required coordinated labor and logistical support, was especially vulnerable. As populations collapsed, the empire could no longer sustain the extraction and refining systems that had fueled centuries of coinage and luxury production.

Marine sediments capture this disruption. Cores from the Aegean show a pronounced decline in lead levels during the sixth century, corresponding with the Justinianic Plague. The scale of the drop suggests that major mining operations ceased or slowed dramatically. The environment responded quickly, with ecosystems showing measurable recovery within decades.

The Justinianic Plague illustrates how demographic collapse translated directly into ecological change. The silence of furnaces and the abandonment of mines left a chemical signature just as strong as the centuries of activity that preceded it.

Plagues as Environmental Turning Points

The Roman pandemics reveal a consistent pattern: when populations declined, pollution decreased. These crises reduced the demand for coinage and luxury goods, disrupted the labor needed to mine and refine metals, and weakened the state’s ability to organize production.

The environment, long pressured by continuous extraction, experienced moments of reprieve. The sedimentary record provides precise evidence for this process.

Lead levels fall during plague years and rise again as populations recover and mining resumes.

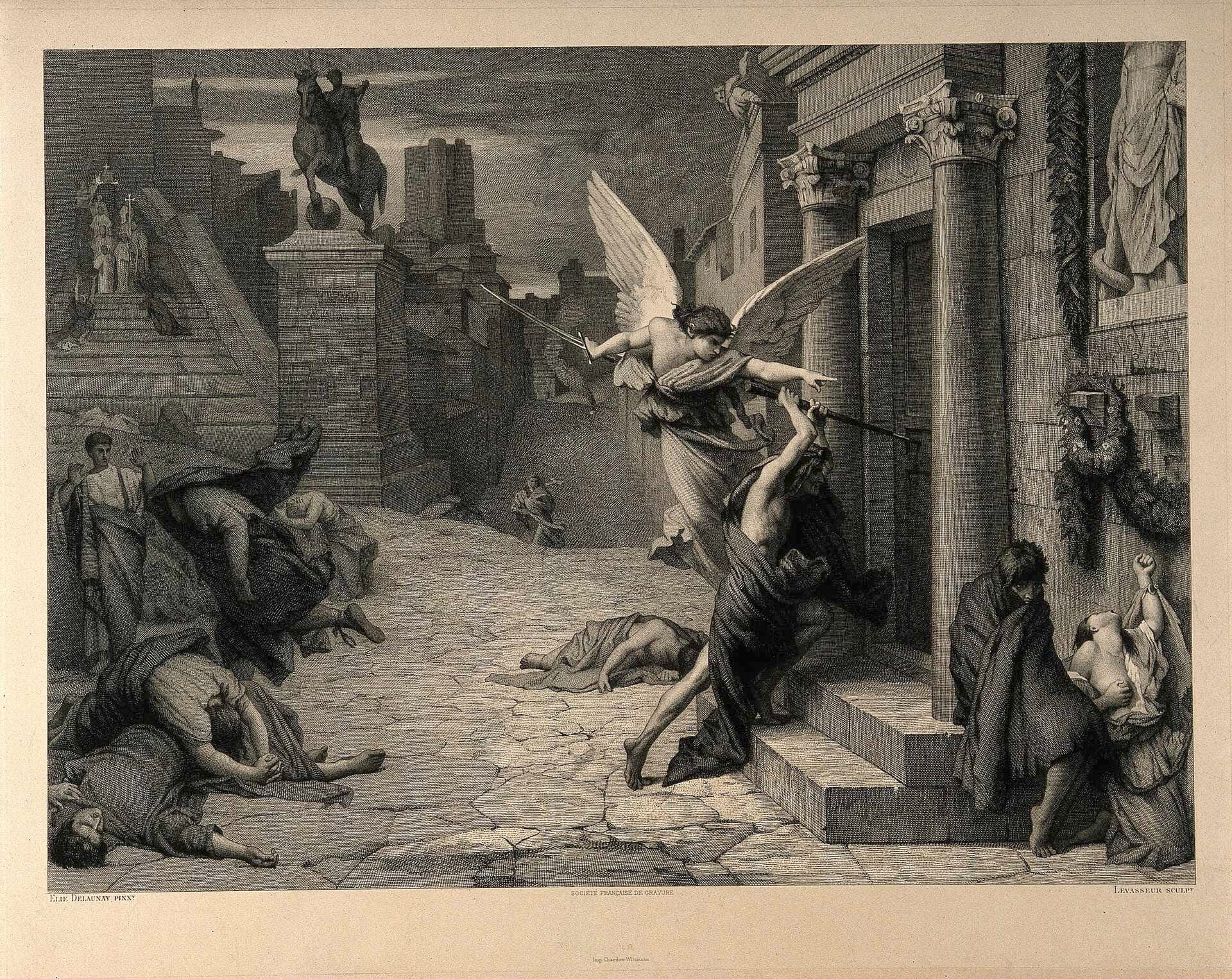

Plague in an Ancient City, from Michiel Sweerts. Public domain

The correlation between historical events and geochemical data strengthens the conclusion that pandemics functioned as environmental turning points. Yet these recoveries were temporary.

Once the immediate crisis passed, the economic and social systems of the empire returned to previous patterns. Mines reopened, furnaces reignited, and pollution resumed. The resilience of Roman society ensured that environmental relief was short-lived. The plagues thus show both the vulnerability and the persistence of imperial systems.

Reading History Through Sediments

The ability to connect plagues to environmental change depends on advances in modern science. By analyzing cores taken from the Aegean seabed, researchers measured the ratio of lead to naturally occurring elements such as zirconium. This method distinguishes human-caused pollution from natural geological variation. Radiocarbon dating of organic material within the cores provided a timeline, while comparison of multiple sites ensured accuracy.

The results are striking. Peaks in lead concentrations align with periods of economic stability and expansion, while troughs correspond to pandemics and crises. The decline during the Antonine and Justinianic plagues is particularly clear, confirming that major societal disruptions left an environmental trace.

This approach represents a new way of reading history. Texts and inscriptions record human experiences of plague, while sediments preserve the ecological consequences. Together, they provide a fuller picture of how pandemics reshaped both society and nature in the Roman world.

Long-Term Ecological Implications

Although the recoveries were temporary, they show how sensitive the Mediterranean was to changes in human activity. Lead levels fell quickly when mining ceased, demonstrating that ecosystems responded rapidly to reduced pressure. Forests cleared for charcoal had a chance to regenerate, rivers carried fewer pollutants, and the air grew cleaner.

The resilience of natural systems contrasts with the fragility of human ones. While the empire struggled to recover from plagues, the environment showed signs of immediate improvement. This pattern highlights the interconnectedness of human and ecological systems. Rome’s prosperity drove pollution, while its crises provided relief.

The long-term implication is that even pre-industrial societies were capable of altering environments on a large scale, but also that nature retained the capacity to recover when given the opportunity. The sediments of the Mediterranean preserve this dynamic, showing both the costs of empire and the possibilities of ecological resilience.

Roman Pandemics and the Environment

The great plagues of the Roman Empire were moments of immense human suffering and political disruption. Yet they also reveal how closely linked human activity and environmental change were in antiquity. When disease reduced populations and halted industry, the Mediterranean experienced measurable recovery from pollution.

This pattern, visible in marine sediments, shows that pandemics acted as unintentional conservation events. They interrupted the continuous extraction and refining that had filled the atmosphere and seas with lead. The declines in pollution demonstrate that even the most powerful empire of antiquity could not sustain its environmental impact during times of demographic collapse.

In studying these episodes, we gain insight into both Roman history and the history of the environment. Plagues reshaped the empire’s politics and society, but they also reshaped its seas. The Mediterranean remembers not only the grandeur of Rome but also the silence of its mines during times of crisis. (Communications Earth & Environment, by Koutsodendris et al.)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: