Did the Romans Know Nessie? Exploring Roman Links to the Loch Ness Monster

A Roman Nessie? The literary record is quiet, yet northern stones, a saint’s tale on the River Ness, and a 20th-century media storm keep the question alive.

The name Loch Ness conjures an image faster than any citation: a long dark trough of water and, somewhere beneath it, an unknown. The historical question that concerns a Roman-minded reader sounds deceptively simple—did Romans know about a creature in these waters?—but meaningful answers rarely arrive at the surface.

A Question Cast into Deep Water

The evidence lives in different registers that hardly ever speak to one another directly. Northern stones cut with animals and symbols resist easy labels and tidy identifications. A saint’s life set on the River Ness, written a century after its events, offers a miracle story that places danger in the water and holiness on the bank.

The interwar years recast the loch as a modern stage, where a new road, a famous photograph, and organized searches turn a local story outward. Late-twentieth-century expeditions bring instruments—the disciplined gaze of lenses and sonar—without providing a final specimen. Rather than beginning with a verdict, the available material unfolds in roughly the order that a curious reader would meet it:

- First iconography (what the early stones say without words),

- then hagiography (what a structured miracle story records about local belief),

- next the modern revival (how cameras, roads, and media reframed the loch),

- and finally scientific appraisal (how evidence is sorted, tested, and found either wanting or suggestive).

Only once those layers have had their say do we return, at the end, to the question of Rome’s knowledge. What the sources do not say matters as much as what they do; silence need not be emptiness if it is correctly situated.

Before (and around) Rome: Pictish Symbols and Water Beasts

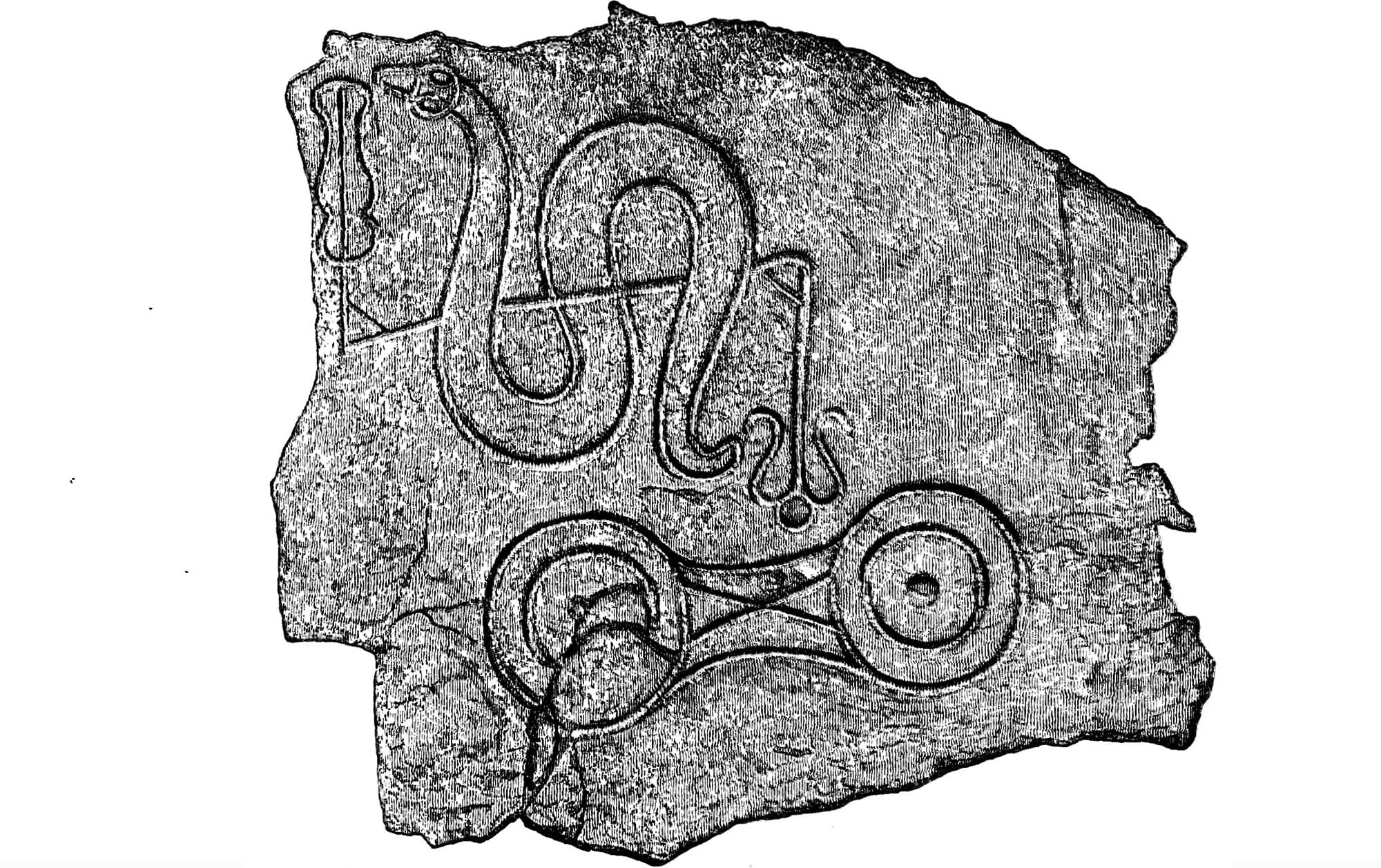

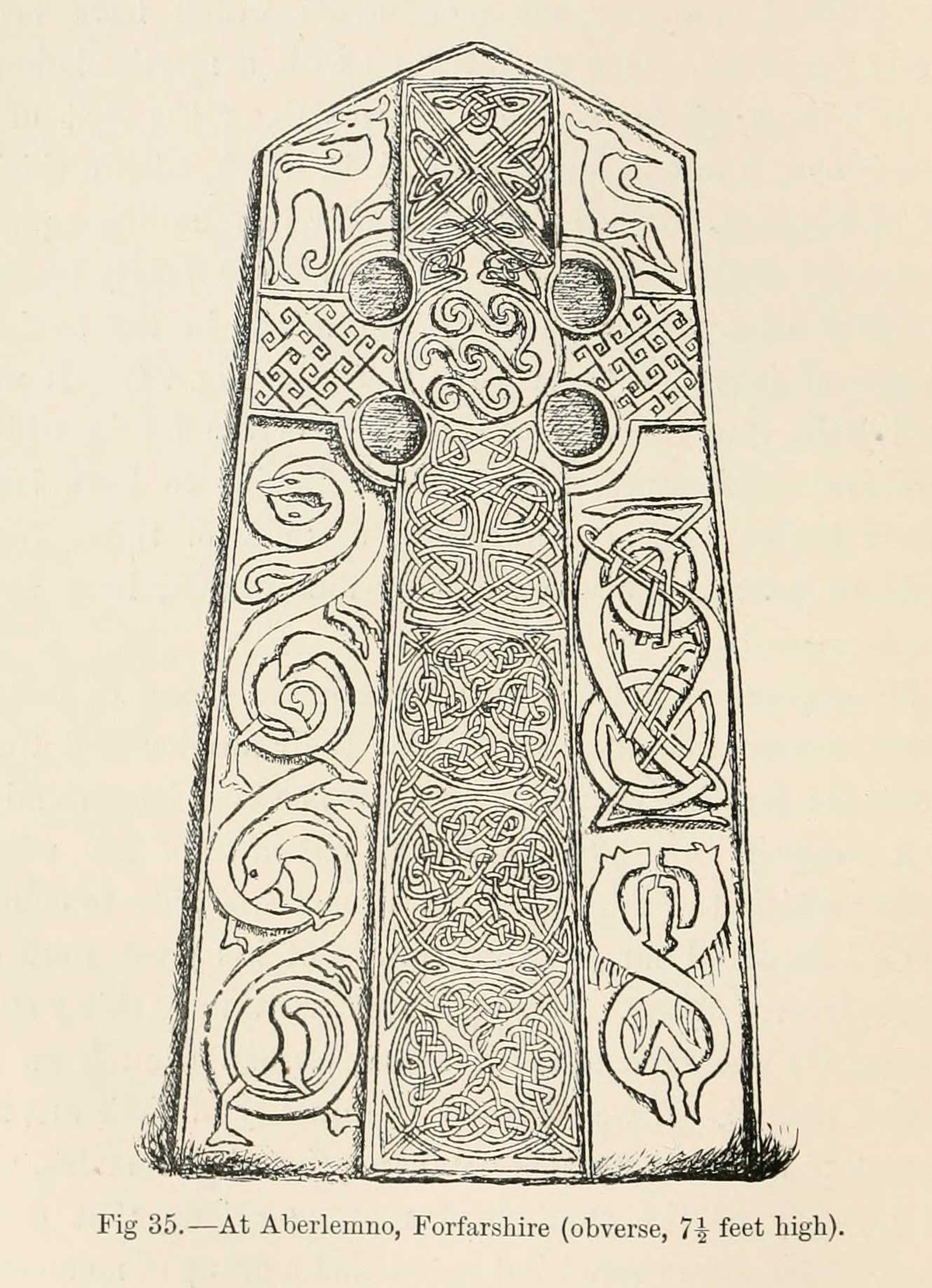

Across northern and eastern Scotland, places that Romans had their mind set upon when conquering Britain, stand the Pictish symbol stones, carved slabs and pillars whose vocabulary includes animals (recognizable and not), objects, and paired signs. Among this repertoire, scholars note an enigmatic figure commonly called the “Pictish Beast.”

Its outline—arched back, an elongate snout or beak, sometimes a curled appendage—does not neatly match any standard fauna. The result is a motif that invites hypotheses without fastening on a single answer.

Some envisage an aquatic identity; some see a mythic composite; some treat it as a heraldic or name-marker, significant more for social meaning than for zoology. The stones serve purposes as various as memory, status, boundary, or ritual, and the beast moves among those settings without a caption.

Two orienting cautions help keep the stones in proportion. First, they do not label a Loch Ness Monster; they are widely distributed and do not confine themselves to the Great Glen. Second, while a few stones belong to the period of Roman presence in Britain, much of the corpus is late antique to early medieval, produced in a milieu where imperial administrators do not set the terms.

What the stones do establish, however, is clear: northern Britain's communities had visual frameworks for potent, sometimes water-associated creatures long before the modern legend cohered. If Roman soldiers, scouts, or merchants consumed local gossip around a Highland hearth, those stories would have found an immediate fit in this sort of imagery—whether or not that talk ever reached Latin prose.

The attraction of the stones, from the standpoint of historical method, lies in what they cannot do as much as in what they can. They do not prove a zoological population in any loch. They do not name locations.

But they do demonstrate a northern imagination that took seriously the possibility of strong, strange beings associated with water. When later textual traditions begin to tell explicit river-beast stories in the Ness district, they land on cultural ground already prepared by images.

After Rome: St. Columba and the Water Beast (AD 565)

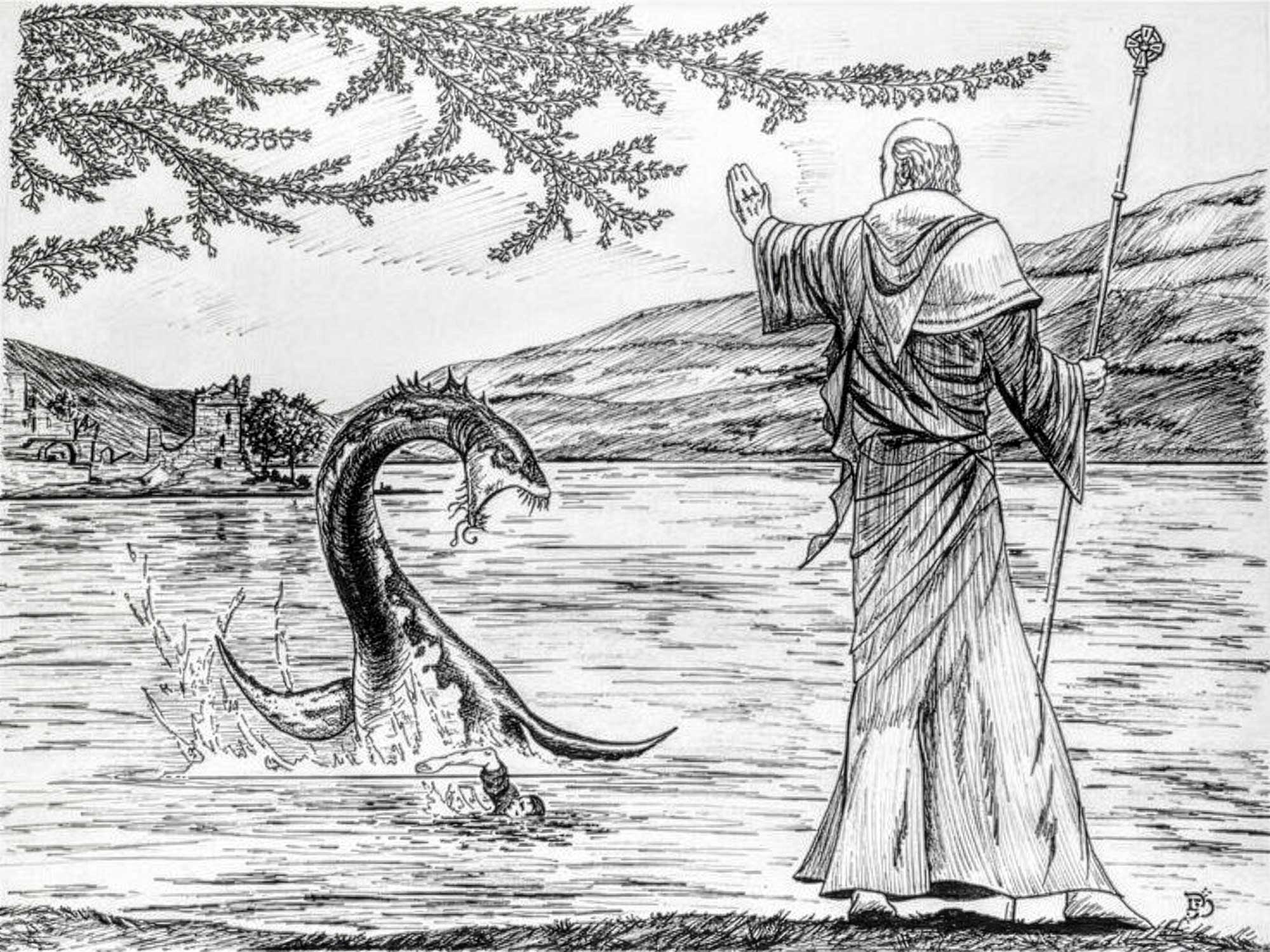

The first sustained narrative to place a fearsome creature in the Ness district does not appear in a Roman itinerary or a provincial gazetteer. It is found instead in a saint’s life, written with devotional purpose: Adomnán of Iona’s Vita Columbae, composed about a century after the events it recounts.

In one episode, usually dated to AD 565 and set near Inverness, locals are preparing to bury a man said to have been “bitten” by a “water beast.” Columba orders a companion to swim the River Ness.

When the creature surges toward the swimmer, the saint raises his hand, invokes the sign of the cross, and commands the beast to flee. The animal withdraws, and the onlookers praise God. The passage writes:

On another occasion also, when the blessed man was living for some days in the province of the Picts, he was obliged to cross the river Nesa (the Ness); and when he reached the bank of the river, he saw some of the inhabitants burying an unfortunate man, who, according to the account of those who were burying him, was a short time before seized, as he was swimming, and bitten most severely by a monster that lived in the water; his wretched body was, though too late, taken out with a hook, by those who came to his assistance in a boat.

The blessed man, on hearing this, was so far from being dismayed, that he directed one of his companions to swim over and row across the coble that was moored at the farther bank.

And Lugne Mocumin hearing the command of the excellent man, obeyed without the least delay, taking off all his clothes, except his tunic, and leaping into the water.

But the monster, which, so far from being satiated, was only roused for more prey, was lying at the bottom of the stream, and when it felt the water disturbed above by the man swimming, suddenly rushed out, and, giving an awful roar, darted after him, with its mouth wide open, as the man swam in the middle of the stream.

Then the blessed man observing this, raised his holy hand, while all the rest, brethren as well as strangers, were stupefied with terror, and, invoking the name of God, formed the saving sign of the cross in the air, and commanded the ferocious monster, saying, "Thou shalt go no further, nor touch the man; go back with all speed."

Adomnán's the Life of St. Columba, Founder of Hy

A careful reading keeps three distinctions straight:

- Geography: the scene is on the river, not necessarily inside Loch Ness, although the river flows from the loch and the tradition soon binds the two.

- Genre: a hagiography seeks edification, not natural history; miracle stories demonstrate sanctity set against danger.

- Historical value: the account shows that, by the sixth century, people in the Ness district told stories about a dangerous creature in the water, and that Christian authors could repurpose such stories to exhibit holy power.

It does not, on its own, establish a breeding population, and it says nothing directly about what Romans did or did not know. What it does reliably provide is a literary touchstone that later writers and modern enthusiasts return to whenever the early history of the legend is in view. (The Loch Ness Monster, by D.G. Gowler)

The Modern Revival: Road, Reports, and the “Surgeon’s Photograph” (1933–1934)

The version of the story most readers carry today coalesces in the interwar years. In 1933, improvements to the A82 along the north shore created long, stable sightlines over the water. That civil-engineering decision coincided with an upturn in reported sightings, a link noted in mid-century summaries and reaffirmed in later reviews.

Descriptions vary: dark humps like an upturned boat; disturbed wakes that seem to move against a pattern; in fewer cases, a head and neck. The following year delivers an image that becomes emblem: the “Surgeon’s Photograph” (1934), printed in the Daily Mail, a small silhouette rising from a calm surface. It is reproduced so often that for many readers it replaces argument with an icon.

The photograph’s afterlife becomes a debate in its own right: allegations of hoax; rejoinders that the hoax narrative itself contains gaps and contradictions; the observation that even a genuine photo of a small object would prove little about what, if anything, lives beneath.

Yet the more important transformation is structural. The loch becomes a modern stage. Organized watches set up along the shore. Expeditions tow sonar across transects. Photographers attempt submerged shots in the same windows when instruments report large targets.

The Dinsdale film (1960) enters this dossier as a recurrent point of reference: a triangular dark hump moving at speed with a heavy wake, then compared against a control boat filmed on the same path. Photo-interpreters, television programs, and later analysts revisit the frames, while expeditions log additional sonar returns at depth and report occasional underwater images.

These modern materials do not compel a single reading, but together they set the terms of twentieth-century discussion: how to value eyewitness testimony; how to weigh a handful of photographs and films that invite competing explanations; what to make of instrument traces that register as large and moving without resolving into a species. (The Loch Ness Monster, by D.G. Gowler; The case for the Loch Ness "Monster": The scientific evidence, by Henry Bower)

Scientific Appraisal: Evidence, Energetics, and Interpretation

The scientific discussion turns on recurring categories of evidence and a single basic constraint:

- Eyewitness testimony has volume and pattern. Many accounts describe dark coloration; a rough, hide-like texture rather than scales; vertical sinking rather than an arcing dive. In the sciences, testimony is suggestive but not determinative. It organizes a search; it does not decide it.

- Photographs and film polarize interpreters. Supporters look to wake geometry and silhouette stability and point to sequences—such as in the Dinsdale film—where a control boat filmed at similar range behaves differently. Skeptics point to birds, otters, logs, and complex wave dynamics in a long, dark loch, any of which can mimic form at low resolution. Enhancement and expert review sharpen frames without erasing ambiguity.

- Sonar records accumulate over decades. Multiple expeditions log large, moving targets at depth; at times, underwater photographs are taken in near-synchrony with instrument detections. Even so, interpretation remains contested. Fish shoals, thermal layers, debris, instrument artifacts, and local bathymetry can produce puzzling returns. Sonar remains promising yet inconclusive.

- Underwater photography produces occasional frames—flipper-like shapes, textured surfaces—that draw attention chiefly when paired with sonar targets. Arguments hinge on contrast, distance, and whether enhancement alters content or simply clarifies it.

- Ecological capacity asks the hard, non-iconic question: could Loch Ness support a breeding population of very large predators? Using energy-flow and standing-stock reasoning, some limnological exercises suggest that a small number might be ecologically possible in an oligotrophic lake, while others respond that a viable population should have left collateral signs: carcasses, bones, consistent surface behaviors. These calculations do not settle existence; they stress-test plausibility.

Taken together, the modern dossier supports a cautious middle line: Loch Ness offers a handful of intriguing records—film, sonar, photographs—yet insufficient proof for a new species. The strongest pro-monster case leans on the Dinsdale film, repeated sonar echoes, and underwater images coincident with sonar. The skeptical stance emphasizes alternative readings and the lack of replicable, unambiguous records. Taxonomy remains unclaimed. (The case for the Loch Ness "Monster": The scientific evidence, by Henry Bower; The Population Density of Monsters in Loch Ness, by R.W. Sheldon and S.R. Kerr)

What the Roman Record Shows—and Why the Legend Outran It

After stones, saints, cameras, and sonar, the original question can be faced squarely. On the specific point of Romans and Loch Ness, the surviving classical record is silent: there is no Roman text that reports a creature in the loch.

Writers who mention northern Britain—military narratives, geographical sketches, ethnographic notes—do not attach a lake-monster to the Great Glen. Keeping this statement for the end gives it the correct weight: it is a conclusion drawn with the surrounding evidence in view, not a teaser designed to end inquiry.

Three observations locate that silence:

- First, local communities had a visual language for powerful, possibly aquatic beings—the Pictish stones—that functioned without textual mediation. Roman validation was not required for those images to carry meaning.

- Second, the earliest literary scene comes later, in Adomnán’s account of St. Columba on the River Ness. As hagiography, it showcases sanctity rather than zoology, but it preserves a memory of danger in the water and of a tale that listeners in the district would understand.

- Third, the modern period reframed the issue entirely. The 1930s brought a road with uninterrupted sightlines, a photograph ready for the front page, organized searches, and then instruments—sonar and cameras—that kept the question open without closing it.

A direct Roman testimony would be a notable find, but its absence is not unexpected. Roman provincial prose seldom recorded local lake lore, and the survival of texts for northern Scotland is thin.

Tacitus’s Agricola recounts the governor’s northern campaigns in Caledonia without a single aquatic beast in the Great Glen. Roman itineraries, military dispositions, and later imperial summaries likewise pass over the loch’s waters in silence. (The Loch Ness Monster, by D.G. Gowler; The case for the Loch Ness "Monster": The scientific evidence, by Henry Bower; The Population Density of Monsters in Loch Ness, by R.W. Sheldon and S.R. Kerr)

The cautious summary is therefore straightforward: Romans left no record of a Loch Ness monster; what we have though is Picts (who lived there ages before the Romans) sharing stories about mythological creatures, then dead silence from the Romans, and after that a sudden surge of new stories, fueled by the Christian and Late Pict stories from St. Columba onwards.

So, it is either that Roman records of monster tales are lost, or–most likely–that Romans, actually being pragmatic, never believed the stories unless they were actually confirmed; since they were, they is no written record. Thus, the world awaited for strong scientific evidence to see that there is nothing in the Loch, but in truth, if they looked to the Romans, they would have found the truth much earlier.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: