Did Romans and Greeks have Abortions and Contraceptives?

Ancient societies tried to manage fertility with resources available in their environment, even though their effectiveness was uncertain and occasionally hazardous.

In a shadowy corner of ancient Rome, beneath the elegant verses of Ovid and the solemn pages of Hippocrates, lies a hidden story—the complex and often controversial world of contraception and abortion in antiquity. Greek and Roman society, far from passive observers, actively grappled with questions of fertility, morality, and bodily autonomy, employing methods ranging from mystical herbs like silphium to sophisticated medical procedures documented by pioneering physicians.

Through ancient poetry, philosophy, and law, we uncover a nuanced reality where decisions about life and reproduction were carefully negotiated within households, debated in philosophical circles, and subtly embedded in everyday life. Exploration and research reveals not only the ingenuity of ancient medical practices but also the timeless tensions surrounding one of humanity's most intimate choices.

Between Life and Law: Abortion and the Ethics of Ancient Civilizations

Throughout history, the ethics surrounding abortion have consistently mirrored the deeper values, medical understanding, and cultural priorities of civilizations. Far from being merely a modern debate, abortion occupied a controversial and nuanced place in ancient societies, from Greece and Rome to Egypt and Persia.

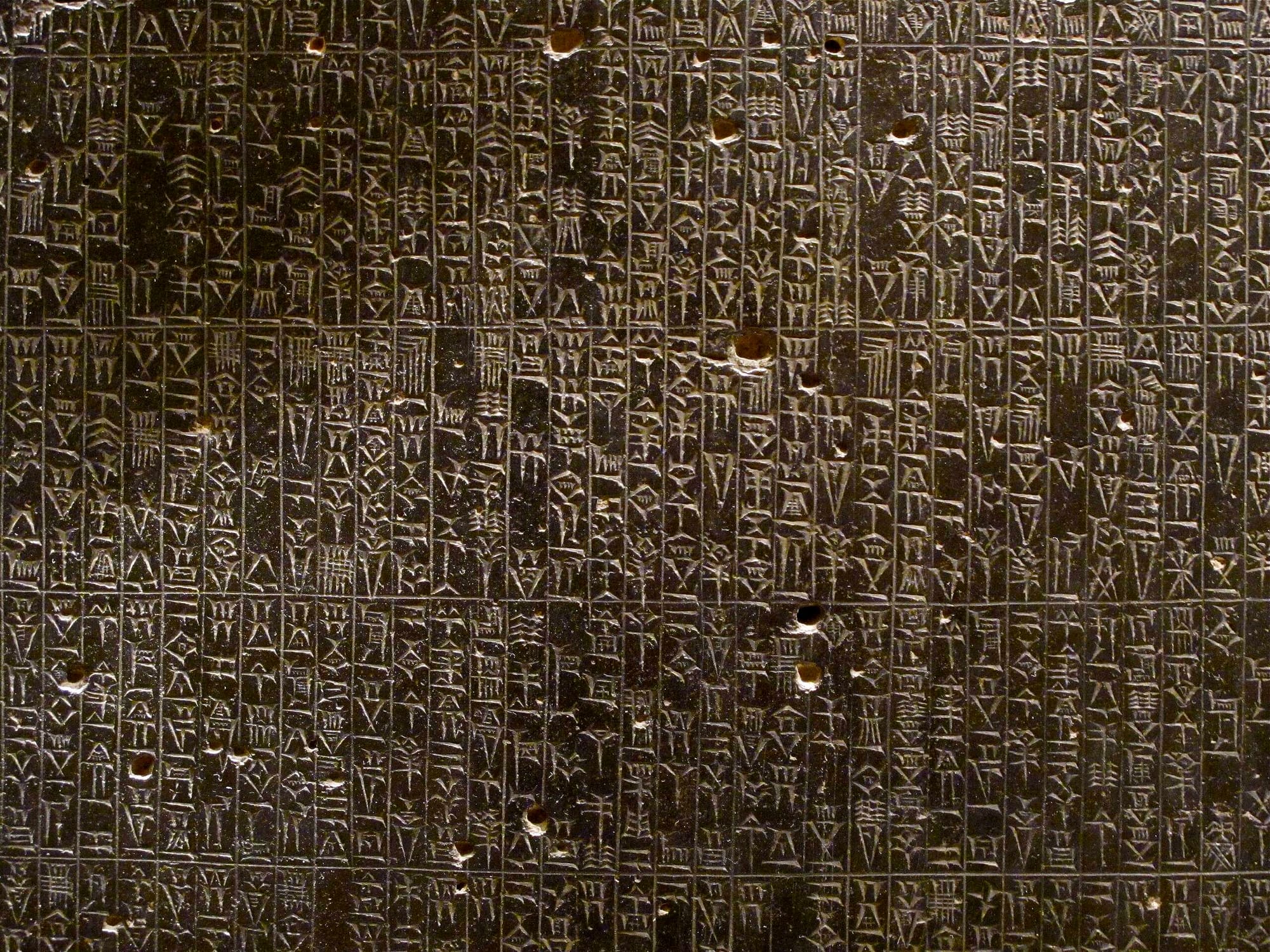

The attitudes and legal frameworks surrounding abortion did more than regulate medical practice—they reflected each civilization’s broader ideas about life, autonomy, gender roles, and morality. While ancient Chinese texts treated the fetus as non-living and thus permitted abortion without moral conflict, ancient Mesopotamian societies, such as those guided by the Code of Hammurabi, administered severe penalties for abortion, contrasting starkly with permissive attitudes toward infanticide.

Although the Egyptians documented abortive methods in medical papyri, no clear legislation survives, suggesting complex societal perspectives that differed significantly from their contemporaries. Exploring these varying approaches provides profound insights into the values, ethics, and medical advancements of ancient cultures.

Abortion and Ethics in Ancient Greek Thought

Although ancient Greek city-states lacked a unified legal stance on abortion, writings from prominent philosophers indicate varying degrees of acceptance. Plato (428–348 BC), for example, considered abortion acceptable for women over the age of 40, while Aristotle (384–322 BC) viewed abortion as a method of family planning.

In contrast, the Pythagorean school opposed abortion entirely, believing that the human soul entered the body at fertilization, thus classifying abortion as murder. Similarly, the Hippocratic Oath (460–370 BC) explicitly prohibited physicians from providing pessaries to induce miscarriage.

“I will use those therapeutic regimens which will benefit my patients according to my greatest ability and judgment, and I will do no harm or injustice to them; neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course; similarly I will not give to a woman a pessary to cause abortion.”

Hippocratic Oath

However, the authenticity of this prohibition has been debated, with some scholars suggesting that it was a later addition influenced by Pythagorean philosophy. These researchers highlight that Hippocrates himself may not have viewed the fetus as possessing life or a soul at conception, but rather only after 40 days for a male fetus and 90 days for a female fetus.

Abortion in Ancient Roman Society: Law, Medicine, and Religion

In ancient Rome, the fetus was not regarded as a living human, and abortion was therefore not classified as a criminal act. A husband could legally permit his wife to terminate her pregnancy; however, if she had an abortion without her husband's consent, he possessed the legal right either to punish or divorce her.

Abortion in Roman society appears primarily motivated by social and economic considerations, and some scholars even recognized it as a legitimate medical practice. For example, the physician Soranus, active in the 2nd century AD, recommended abortion when pregnancy posed a medical risk, such as when the uterus was underdeveloped, affected by irregular swellings, or compromised by other medical complications.

Although strongly opposed by early Christian leaders—including Tertullian (155–222 AD), Cyprian (200–258 AD), and Saint Basil (320–379 AD)—abortion remained common practice until around 374 AD. The Christian opposition solidified in the Council of Ancyra in 314 AD, where church authorities decreed a ten-year penitential period for women who underwent abortion. (An investigation into the ancient abortion laws: Comparing ancient Persia with ancient Greece and Rome, by Hassan Yarmohammadi, Arman Zargaran, Azade Vatanpour, Ehsan Abedini)

Contraceptive Practices in Ancient Greece and Rome

Ancient Greek and Roman societies employed various contraceptive methods, reflecting practical approaches to reproductive control. Prominent among these was the use of silphium, whose seeds were ingested orally or used vaginally through wool soaked in its juice to prevent pregnancy.

Another popular contraceptive recommended by the Roman physician Soranus involved olive oil, either alone or combined with honey, cedar resin, balsam tree juice, or white lead, which acted as a primitive spermicide by impeding sperm mobility. Juniper berries, when crushed and applied to the genital area, were believed to reduce fertility by obstructing implantation.

Some unconventional methods included the induction of sneezing immediately after intercourse, theorized to expel semen and thus prevent pregnancy. These methods demonstrate ancient societies' efforts to manage fertility with resources available in their environment, even though their effectiveness was uncertain and occasionally hazardous. (A Literature Review on Reckless and Hazardous Contraceptive Practices used since Primeval Times, by Bhumika Chauhan & Monica Misra)

Silphium: The Lost(?) Treasure of Greek and Roman Medicine and Cuisine

Silphium was an herbaceous plant greatly esteemed in ancient Greek and Roman societies for its medicinal and culinary properties. Native solely to Cyrene (modern-day Libya), silphium became a significant economic asset, prominently depicted on local currency due to its immense value.

The ancient Greek botanist Theophrastus provided one of the earliest and most comprehensive descriptions, noting its thick root, celery-like leaves called maspeton, and leaf-like seeds termed phyllon. He emphasized its two distinct juices, collected separately from the root and stalk, widely used for medicinal purposes. Dioscorides, the prominent pharmacologist, mentioned its healing properties extensively, including its effectiveness for bruises, tumors, toothaches, and as an antidote against various poisons.

Hippocrates frequently cited silphium as a remedy for respiratory diseases, digestive problems, and as an abortifacient, underscoring its medical significance.

A closeup of the Ferula communis, a plant family rumoured to be the extinct Silphium. Credits: Sarah Gregg, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Galen also discussed silphium, emphasizing its warming properties, and its effectiveness in treating conditions such as sciatica, dental pain, and even animal bites. In Roman literature, Pliny the Elder noted silphium’s broad medicinal applications, such as treatments for inflammation, wounds, and as an emmenagogue.

The culinary significance of silphium is documented by Athenaeus and Apicius; both Greek and Roman cuisines heavily relied on the plant as a flavorful seasoning, typically combined with vinegar, honey, or olive oil. Athenaeus provided culinary insights from earlier Greek writers, while Apicius included numerous recipes featuring silphium, reflecting its integral role in ancient cooking.

Despite its considerable cultural and economic importance, silphium mysteriously vanished from the historical record, likely due to overharvesting and ecological changes, leaving its identity and true properties as subjects of enduring historical curiosity. Some scholars have recently rediscovered traces of the legendary plant, which is believed to be not lost, but naturally migrated into other areas. (The Silphium Plant: Analysis Of Ancient Sources, by Valentina Asciutti)

Ancient Roman Birth Control and Abortion: Herbal Remedies, Pessaries, and Folk Practices

Silphium was so valuable that the Cyrenian settlers who discovered it became renowned and amassed great wealth. The demand for silphium was so high that its image was stamped onto Cyrenian coins, sometimes accompanied by a depiction of a woman beside the plant. One notable coin even features a seated woman reaching toward the plant while gesturing toward her reproductive organs (we have to note that a few scholars argue this is a misinterpretation of the coin; it could well be the Goddess Cyrene, and the plant).

Soranus of Ephesus, a Greek physician from the 1st or 2nd century CE, recorded that consuming “Cyrenaic balm” could stimulate menstruation. He prescribed an amount equivalent to a chickpea mixed with water. While the precise method of consumption is unclear, it was likely crushed and ingested with wine or water.

However, Soranus warned that the plant was not merely a contraceptive but could also terminate an existing pregnancy. His opposition to abortion led him to caution against its use, noting side effects such as stomach distress and congestion of the head. Pliny the Elder, while also discussing silphium’s contraceptive properties, refrained from labeling it as an abortifacient. Despite concerns over its use, silphium remained highly sought after. By 93 BCE, thirty pounds were imported to Rome.

However, by 54 CE, Pliny reported that only a single stalk remained, which was sent to Emperor Nero as a rarity.

A possible representation of Emperor Nero receiving the last stalk of silphium in the Empire. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

Knowledge of silphium persisted into late antiquity. A gynecological text from the 3rd or 4th century CE, On the Diseases and Cures of Women, written by a woman who either assumed the identity of Cleopatra VII or a physician in her court, included silphium in a formula guaranteeing immediate abortion.

The recipe combined bull bile, pepper, rue, asphaltum, and silphium; if the plant was extinct by then, the author may have relied on earlier sources or documented a long-lost Egyptian method. If the plant’s extinction was misreported, then we have evidence the plant actually survived.

Another herb frequently employed for contraception was pennyroyal, known in antiquity as Glechium. Dioscorides wrote that when consumed, it could induce menstruation. Galen, the renowned Greek physician, similarly classified it as an emmenagogue, a substance that stimulates menstrual flow. On the Diseases and Cures of Women also recommended combining pennyroyal with wine for its abortive effects.

Its widespread recognition is evident in Aristophanes’ plays—Hermes humorously reassures a character that pregnancy will be avoided with a “dose of pennyroyal.” Another jest in Lysistrata describes a woman as “spruced with pennyroyal,” implying that she was not pregnant, a reference that would have been well understood by the audience.

Although commonly used, pennyroyal was highly toxic, capable of causing liver and kidney failure, yet ancient sources make no mention of its dangers.

A typical sample of the Pennyroyal plant. Credits: Katya, CC BY-SA 2.0

Balm of Gilead, so named for its origin in the Gilead region, was another botanical remedy. Dioscorides described it as an abortifacient that could also expel afterbirth, while Soranus suggested that applying its juice to the cervix could prevent conception. Pliny, despite documenting its high value—reportedly twice its weight in silver—made no reference to its medicinal applications.

Sage, though widely used today, differed in antiquity. Pliny identified it as a type of wild lentil with emmenagogue properties, noting that when applied externally, it could expel a dead fetus. Dioscorides similarly recorded that a decoction of its leaves could stimulate menstrual flow and function as an abortifacient. Unlike his usual neutral descriptions, he condemned the practice, stating that the most immoral women applied it as a pessary for abortion.

The squirting cucumber, Ecballium elaterium, was another potent abortifacient. Dioscorides stated that when used as a pessary, it could induce menstruation and pregnancy termination. Pliny acknowledged its ability to provoke menstrual discharge but cautioned that it could also cause miscarriage. Hippocrates, in De Mulierum Affectibus, identified it as the most effective abortive pessary, making him one of the few ancient physicians to express a preference among such remedies.

Another well-documented contraceptive and abortifacient was Daucus carota, commonly known today as Queen Anne’s Lace. Dioscorides detailed that its seeds could induce menstruation when ingested or used as a pessary. Pliny also referenced it but only briefly. Its use persisted beyond antiquity—medieval Latin texts such as the Antidotarium Nicolai contained recipes for abortifacients featuring Queen Anne’s Lace, along with pennyroyal and birthwort. Interestingly, these medieval formulations often avoided direct reference to abortion, instead claiming to “expel a dead fetus” or regulate menstruation.

Birthwort (Aristolochia clematitis), mentioned in De Materia Medica, was another plant known for its dual nature. Dioscorides identified it as an abortifacient when consumed with pepper and myrrh or used as a pessary. However, Pliny recorded a related variety, aristolochia plistolochia, which was thought to promote pregnancy rather than prevent it. He believed that when applied immediately after conception, it could ensure the birth of a male child, suggesting confusion in identifying the correct species for different uses.

Photo #1: The Ecballium exploding cucumber plant, close up. Credits: Lazaros Papandreou from Getty Images, by Canva

Photo #2: Close up of the balm of Gilead flower on the way. Credits: Elosoblues from Getty Images, by Canva

Photo #3: The sage plant, close up. Credits: pashapixel from Getty Images, by Canva

Photo #4: A closeup of an open Daucus Carota Flower. Credits: Alain de Maximy, by Canva

Photo #5: A closeup of the common birthwort. Credits: Nahhan from Getty Images, by Canva

In addition to botanical methods, ancient doctors also prescribed mechanical contraceptives. As aforementioned, Soranus recommended applying old olive oil or honey to the cervix before intercourse, believing it would seal the uterus and prevent conception. Wool was sometimes added to aid clotting.

While honey has been studied in modern times for potential contraceptive effects, results have disproven its efficacy. Another method involved inserting wool soaked in a mixture of white lead and cedar or balsam sap into the cervix. This was likely ineffective as a barrier but may have caused infertility due to lead poisoning, which ancient physicians misinterpreted as proof of contraception.

Beyond medical approaches, various folk beliefs circulated regarding pregnancy prevention. Soranus advised that women could avoid conception by holding their breath and pulling away before ejaculation, then inducing sneezing and squatting to expel semen.

He also suggested drinking something cold before intercourse, claiming it would “close the orifice of the uterus” and prevent sperm from entering. Pliny the Elder described a particularly unusual method—women were to extract small worms from a hairy spider’s head, tie them to their bodies with deer hide, and expect a year-long contraceptive effect.

[…] the "phalangium," is a spider with a hairy body, and a head of enormous size.

When opened, there are found in it two small worms, they say: These, attached in a piece of deer's skin, before sunrise, to a woman's body, will prevent conception, according to what Cæcilius, in his Commentaries, says.

This property lasts, however, for a year only; and, indeed, it is the only one of all the anti-conceptives that I feel myself at liberty to mention, in favour of some women whose fecundity, quite teeming with children, stands in need of some such respite.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History

The extensive range of birth control and abortion methods available to Roman women included herbal remedies, pessaries, and folk practices. While medical texts by figures such as Soranus, Dioscorides, Pliny, Galen, and Metrodora lent credibility to these treatments, their safety and efficacy were often questionable.

Some methods, like silphium and pennyroyal, were widely accepted despite their toxicity, while others, like lead pessaries, likely caused harm rather than preventing pregnancy. Nevertheless, these ancient solutions provided women with a sense of control over their reproductive health, shaping medical and cultural attitudes toward contraception for centuries to come. (Controlling their Bodies: Ancient Roman Women and Contraceptives, by Madison Brazan)

Ovid’s Lament on Abortion: A Lover’s Plea and a Poetic Condemnation

Among Ovid’s works, two elegies stand out for addressing a subject rarely found in ancient love poetry: abortion. In the first (2.13), he expresses deep concern for Corinna’s well-being after discovering that she, without informing him, sought to end her pregnancy through unknown means—whether through medicinal intervention or a surgical procedure remains unclear.

“In the foolish attempt to destroy the weight in her belly, Corinna lies exhausted near death.

For taking such a risk without my knowledge she deserves my anger, but out of fear I forget my anger.

I was the father, or so I believe; often I take possibilities as facts.

Isis, ruler of Paraetonium and Canopus' rich fields, Memphis and Pharosrich in palms, and where the broad Nile swiftly pours into the sea through seven mouths, by thy sistrum I pray, by fearful Anubis' face (so may Osiris ever piously love thy rites, so may the snake unambitiously slip past thy gift-horde, and so may horned Apis accompanythy processions) — I pray thee, turn thy face to us and in one woman spare us both, for thou shalt give her life, and she to me.

Often on the appointed days she has dutifully sat where the group of eunuch priests dips thy laurels and thou dost pity girls in labour, whose bodies are distended by the hidden load; be gracious and grant my prayers, Ilythyia, for any girl thou biddest deserves thy munificence.

I myself shall dress in white and offer incense until thine altars smoke, I shall lay the promised gifts at thy feet; I shall add an inscription, OVID GIVES THANKS FOR CORINNA'S LIFE, do thou but justify those gifts and that inscription.

If advice, Corinna, is appropriate in such an emergency, let this be an end of such combat.”

The second poem delivers a scathing critique of abortion itself. Ovid denounces the act in striking terms, stating that the woman who first devised the means to destroy an unborn child deserved to perish by the same violent practice:

"Quae prima instituit teneros convellere fetus, / militia fuerat digna perire sua."

His argument follows a logical extension—if a mother had made the same decision, her child would never have come into existence. He reinforces this idea with powerful imagery, warning that had Venus harmed Aeneas in her womb, the lineage of the Caesars would have been erased from history:

"If llia had killed the twins in her womb all swollen [i.e. Romulus and Remus] the future founder of our city would himself have fallen.

If pregnant Venus had violated Aeneas in her womb, the future world would have been without the Caesars.

You too, with all your beauty, though you might have been born, you would have died if your mother had tried what you have."

Ovid’s words convey both personal anguish and a broader condemnation of abortion’s consequences, leaving his readers with a poetic reflection on life, legacy, and fate.

In his poetry, Ovid recounted failed abortion attempts, while Procopius described how Empress Theodora unsuccessfully tried to abort a late-term pregnancy. These accounts suggest that, while abortion was attempted, it was far from guaranteed to work, particularly in more advanced pregnancies.

"Why defraud the heavy vine of its ripening grapes, or heartlessly tear unripe fruit from the tree? Ripeness will come about naturally; let things grow, once conceived.

Life is well worth a little waiting.

Why excavate your bellies by driving in a needle? Why give lethal poison to the unborn?

Men find fault with Medea, stained with her children's blood, and they complain of Itys whom his own mother killed.

Both women were cruel mothers, no doubt, but driven by drastic motives to wreak vengeance on their husbands by destroying their blood-kin.

What Tereus, what Jason drives you to pierce your bodies in distraction? Even tigresses in Armenian forests have never done this, and no lioness ever presumed to destroy her litter.

But young women do, though not with impunity, for often the girl who kills her own in her womb dies herself and is carried out to the pyre, her hair dishevelled, and the people call out, as they catch sight, 'Quite right, too !'

But may my words vanish in the breeze, and these words of omen count for nought. O ye gods, allow us safely to transgress once, and it is enough: let the second trespass bring the penalty."

Ovid, Amores

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: