Cicero: Orator, Statesman, and Unintended Historian of the Roman Republic

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE) was widely regarded as one of Rome's greatest public speakers and prose stylists. His contributions span politics, law, philosophy, and literature, making him a key figure in Roman intellectual history.

Cicero’s works focus largely on rhetoric, ethics, and political theory, but he also contributed indirectly to historical understanding, particularly through his speeches, letters, and philosophical writings, which provide invaluable insights into the political and social landscape of the late Roman Republic.

Cicero the Philosopher

Cicero is widely recognized as a lawyer and the famous opponent of Julius Caesar, yet his contributions as a philosopher are often overlooked, even by major educational sources. While not typically hailed as a philosophical innovator, Cicero's work played a crucial role in translating key concepts from Hellenistic philosophy into Latin.

He introduced new terms, such as evidence and humanity, helping to shape philosophical discourse in the Roman world. His writings made Greek ideas more accessible to a Roman audience, reflecting his efforts to adapt and refine the philosophical heritage of his time.

Cicero focuses on universal themes, particularly myth, which he updates and reinterprets for his readers, offering his unique versions. His intellectual adaptability shines through as he draws from prominent figures like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, especially emphasizing their dialogical methods.

Additionally, Cicero utilizes his exceptional memory to structure his writings, much like preparing for a public speech, allowing him to organize his thoughts clearly. He also pays attention to his scholarly audience, striving to present his ideas logically and persuasively, ensuring that reason prevails in his arguments.

Moreover, Cicero tends to highlight the commonalities between different philosophical schools, summarizing them in a way that makes complex ideas easier to digest, much like a student preparing for an exam. His ability to transition between different philosophical systems exemplifies the versatility that continues to fascinate scholars, despite the passage of time.

In Academica, Cicero contends that humans can never attain absolute truth, reflecting his skepticism about our capacity for certain knowledge. In contrast, De finibus emphasizes the idea that living in accordance with nature and virtue, striving for physical health and moral perfection, is the central aim of life.

He advocates for belief in a rational higher order, even as he expresses doubt about divinatory practices such as oracles and dreams. Cicero supports the concept of free will, suggesting that despite the existence of destiny, old age can be a peaceful time filled with memories and the anticipation of a better afterlife, with the soul considered immortal.

Cicero sees true friendship as a communion of virtuous souls, unaffected by material interests.

Cicero, from Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres grecz, latins et payens (1584) by André Thevet. Public domain

For him, God symbolizes order, harmony, and unity, while Satan represents chaos and destruction, leading to war and death. These philosophical ideas illustrate how Cicero distilled Greek and Latin knowledge into his work, offering a synthesis of thought rather than presenting a new system. His vast intellectual curiosity and encyclopedic knowledge make him a valuable source for readers, not just as a lawyer or orator, but as a philosopher exploring the complexities of human life and wisdom. (Cicero philosopher, by Fabrizio Spiotta)

Can we Consider Cicero a Historian?

Cicero's role as a literary historian is an intriguing aspect of his intellectual pursuits, given his profound interest in both Greek and Latin literature, which is well-documented through the extensive use of literary quotations and references found throughout his works.

Cicero not only read extensively but often acted as an interpreter of literature, shedding light on his ability to engage with texts in a critical manner. This interest leads us to wonder whether Cicero can also be considered a literary historian, a figure concerned not merely with reading but with understanding and narrating the development of literature itself.

In a fragment from De historicis Latinis, Cornelius Nepos (a Roman biographer), laments Cicero's untimely death, suggesting that had Cicero lived longer, he might have filled the existing gap in Latin historiography. Nepos even posits that it is difficult to determine whether Cicero's death was a greater loss for the Roman state or for history itself.

This indicates that Cicero was widely expected by his contemporaries to undertake significant historical works, a project that was frequently mentioned in his correspondence, particularly with his close friend Atticus. In several letters and conversations, Cicero reveals his intention to write a history of Rome intertwined with the history of Greece, but personal and public challenges prevented him from doing so.

The encouragement Cicero received from his intellectual circle to produce a major historiographical work is a recurring theme in his life. Figures such as Atticus and Lucullus urged him to take on the task, believing that Cicero had the intellectual and rhetorical skills to create a historical account that could rival Greek historiography.

This collective anticipation for a Ciceronian history of Rome reflects what has been described as la vocation historique de Cicéron—his calling to historiography, evidenced by his keen interest in the past and the importance he placed on history as a discipline. Cicero himself famously defined history as testis temporum, lux veritatis, vita memoriae, magistra vitae, nuntia vetustatis:

"...history bears witness to the passing of the ages, sheds light upon reality, gives life to recollection, guidance to human existence, and brings tidings of ancient days".

Despite this recognized vocation, one might question whether Cicero's historical interests were supported by a methodical approach to historical research.

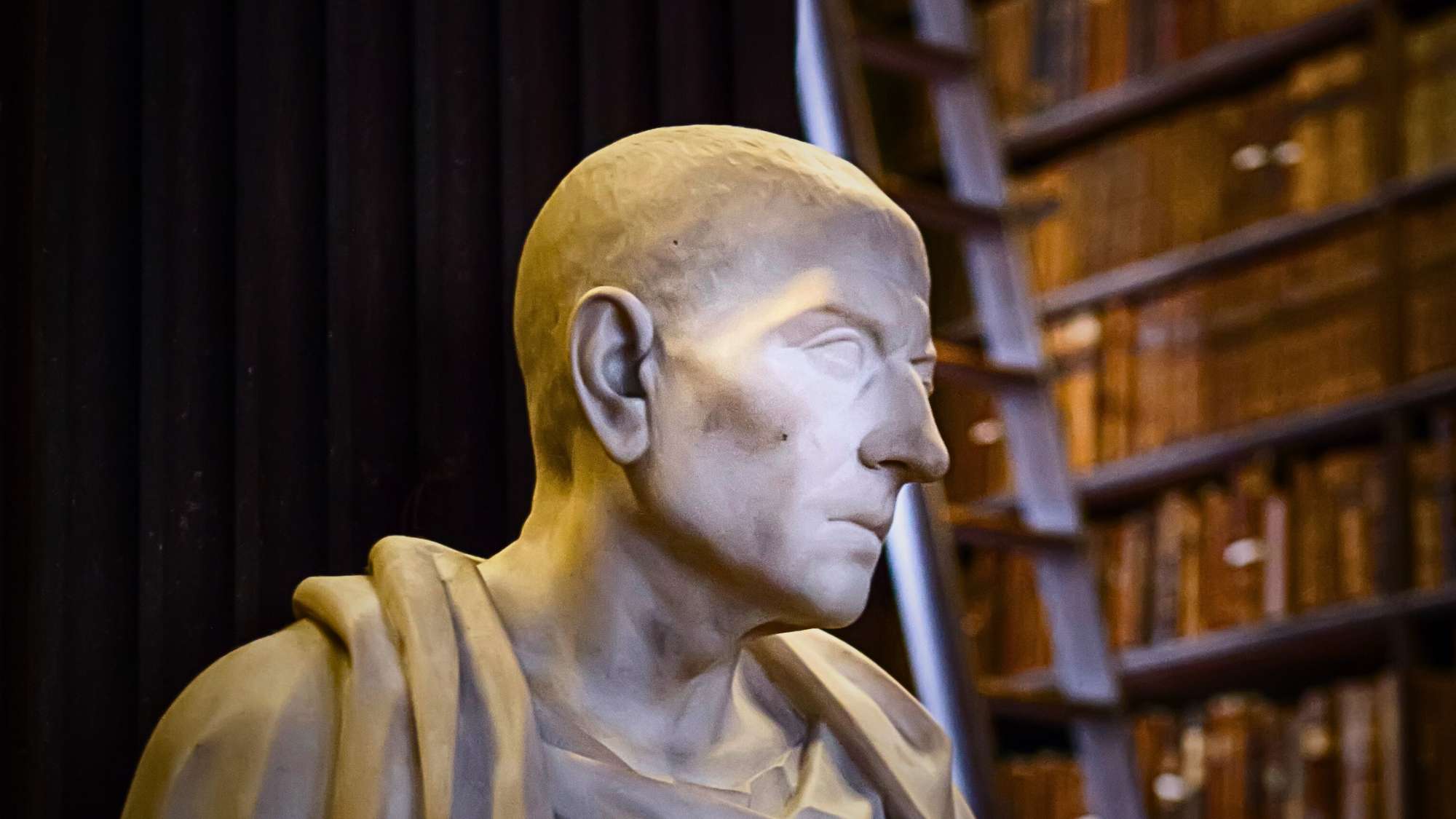

Cicero’s Bust in the Long Room Interior of the Old Library at Trinity College. Credits: nataliiazhekova, by Canva

Scholars have examined Cicero's reflections on historiography, particularly in his epistle to Lucceius and sections of De oratore, as well as his use of historical exempla. Additionally, his body of work contains numerous historiographical digressions, offering insights into various aspects of history, from political and military events to the evolution of Roman laws and cultural traditions.

Cicero's contributions also extend into the realm of cultural history, where he explores the progression of human civilization. His writings, including the early De inventione and the later De officiis, display a broad interest in how human society and its institutions developed over time.

Through these explorations, Cicero can be seen as a figure who was deeply engaged with historical themes, whether in the political, legal, or cultural domains, offering a rich perspective that further positions him as an intellectual with strong historiographical instincts. (Writing Literary History in the Greek and Roman World, edited by Giacomo Fedeli & Henry Spelman)

Cicero’s Life; a Short Biography

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in Arpinum, a hill town located roughly 60 miles southeast of Rome. Coming from a wealthy family within the equestrian order, Cicero's father ensured that both Marcus and his younger brother received a top-tier education, focusing on philosophy and rhetoric, first in Rome and later in Greece.

After a brief stint in the military, Cicero turned his attention to law, studying under the renowned jurist Quintis Mucius Scaevola. His legal career began in earnest in 81 B.C., when he made a name for himself by successfully defending a client accused of the serious crime of parricide.

Cicero was elected to key political positions throughout his career: he became quaestor in 75 B.C., praetor in 66 B.C., and eventually consul in 63 B.C., the youngest person to reach that rank without coming from a traditional political family.

During his time as consul, Cicero successfully thwarted the Catilinarian conspiracy, a plot aimed at overthrowing the Roman Republic. However, in the aftermath, he authorized the summary execution of key conspirators without trial, which was a violation of Roman law. This action left him open to legal repercussions, ultimately leading to his prosecution and subsequent exile.

During his exile, Cicero turned down offers from Julius Caesar that could have ensured his protection, choosing instead to maintain his political independence and avoid becoming part of the First Triumvirate. When the civil war erupted between Caesar and Pompey, Cicero sided with Pompey, but after Caesar's victory, he faced exile once more. He returned to Rome cautiously after receiving a pardon from Caesar.

"All honest men killed Caesar....some lacked design, some courage, some opportunity: none lacked the will."

Cicero, Philippics

Although Cicero was not directly involved in the assassination of Caesar in 44 B.C., he quickly endorsed it and celebrated the act. In the political chaos that followed Caesar's death, Cicero attempted to forge alliances with various key figures. Initially, he supported Mark Antony in the Senate, but later turned against him, delivering a series of harsh speeches known as the Philippics, in which he declared Antony a public enemy.

Antony was really angry by what Cicero was writing about him:

"What is more shameful than that he should be living who set on the diadem, while all men confess that he was rightly slain who flung it away." (Second Philippic)

"What peace can there be, in the first place, between Marcus Antonius and the Senate? With what aspect can he regard you? With what eyes can you in our turn regard him? Who of you will not hate him? Whom of you will he not hate? Come, is it only he who hates you, and you him." (Seventh Philippic)

"I always took the same line before the people; and not only against Antonius himself have I always inveighed, but also against his abettors and agents in crime, both those here and those with him, in a word against the whole house of Marcus Antonius." (Twelfth Philippic)

"When he thinks the death of Caesar should be avenged he proposes death not only for the perpetrators of that deed, but also for those who not resent it." (Thirteenth Philippic)

And finally, a foreboding reference to Cicero himself:

"Brief is the life given us by nature; but the memory of life nobly resigned is everlasting. And if that memory had been no longer than this life of ours, who would be so mad as, by the greatest labour and peril, to strive for the utmost height of honour and glory." (Fourteenth Philippic)

Cicero’s Ultimate Hour

Cicero’s death is one of the most dramatic moments in the political chaos following the assassination of Julius Caesar. Cicero briefly aligned himself with Octavian, but when Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate in 43 B.C., his fate was sealed. His name was included in the proscriptions of the Second Triumvirate—an agreement between Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus to eliminate their political enemies. On December 7, 43 BC, Cicero was captured near his villa in Formiae as he attempted to flee Italy, having been marked for death.

Antony arranged for Cicero to be declared a public enemy, leading to his capture and execution. When the assassins sent by Antony found Cicero, he reportedly did not resist. Accounts describe him as stretching out his neck in a resigned, almost dignified manner, as if ready to accept his fate.

According to Seneca the Elder, as recorded by the historian Aufidius Bassus, Cicero’s last words were “There is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly” (nihil propera, ut scis militiam, modo me bene occide). His killers, led by the centurion Herennius and a tribune named Popilius Laenas, swiftly carried out the execution. Cicero was decapitated, and his right hand, which had penned the speeches against Antony, were cut off as a gruesome display of revenge.

In a final act of brutality, Antony had Cicero’s severed head and hands displayed on the Rostra in the Roman Forum, the very platform where Cicero had delivered his greatest orations. This macabre display was meant as a warning to Antony’s political rivals, symbolizing the violent end of one of Rome’s most eloquent and influential statesmen. Despite the grim circumstances of his death, Cicero’s legacy as a defender of the Republic and a master of rhetoric endured, influencing political thought for centuries to come.

Cicero the Chronicler

Cicero's role as a historian is often debated, particularly in distinguishing his use of historical exempla from more rigorous historical analysis. While Cicero frequently referenced traditional stories and historical examples in his speeches and writings, critics note that his historical knowledge, while effective in adding authority (auctoritas) and pleasure (iucunditas) to his oratory, was not especially deep, up-to-date, or accurate.

He tended to rely on earlier Roman historians and annalists, sometimes conducting additional research for specific cases, but the historical accuracy in these instances was often secondary to his rhetorical aims.

However, Cicero's work occasionally shifted towards a more methodical, antiquarian approach, particularly when he drew on documentary sources or legal precedents, such as in De domo. His connections with the antiquarian tradition, which was flourishing during his youth, likely influenced this tendency. Cicero was acquainted with scholars like Aelius Stilo and closely connected to Atticus, who encouraged his engagement with antiquarian studies.

Image #1: Francesco Zuccarelli, Public domain

Image #2: Paul Barbotti, Public domain

Image #3: Benjamin West, Public domain

His admiration for the past, combined with his legal training, is evident in his works. His intellectual curiosity extended to acquiring and studying ancient texts, such as the library of Ser. Clodius, and his enthusiasm for authors like Dicaearchus. The fascination he expressed with history is also demonstrated in personal anecdotes, such as his discovery of Archimedes' tomb during his time as quaestor in Syracuse, reflecting a personal connection to the past.

Overall, while Cicero's contributions to historical scholarship may not have reached the level of formal historiography, his engagement with antiquarianism and his appreciation for Rome's historical legacy demonstrate a more complex relationship with history. His historical exempla may not always be critically rigorous, but they reveal a deep cultural and intellectual engagement with the Roman past. (The Roman Historical Tradition: Regal and Republican Rome, edited by James H. Richardson, Federico Santangelo — Cicero the historian and Cicero the Antiquarian, by Elizabeth Rawson)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: