Beyond Marcus Aurelius: Lucius Verus, the Shadowed Emperor of Rome's Golden Age

Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus; adoptive siblings and co-emperors, one shining through the centuries, the other fading quietly along history’s winding path.

Overshadowed by the towering legacy of his co-emperor Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus remains one of Rome’s most enigmatic rulers. Despite sharing imperial power during one of the empire’s most challenging periods, his name often lingers in the margins of history.

Was he merely a lavish bon vivant, or did his tenure leave an enduring mark on the Roman world? As we look into the life and reign of Lucius Verus, we uncover a man who, though eclipsed in fame, held the reins of power during a critical era of war, plague, and cultural exchange. What truly lies behind the polished facade of this lesser-known emperor?

Triumph and Shadows in the Roman Near East

Lucius Verus, often shaded by his co-emperor Marcus Aurelius, played a very important role in the defense and consolidation of Roman power in the East. Despite the mixed portrayals of Verus in ancient and modern sources—many focusing on his perceived indulgence rather than his accomplishments—there is compelling evidence of his significant impact during his campaigns against the Parthians from AD 162 to 166.

Verus' military campaign was notable for its strategic successes, including the burning of the royal palace at Ctesiphon and the sack of Seleuceia. However, much of the credit has historically been attributed to his generals, particularly Gaius Avidius Cassius and Publius Martius Verus.

This perception has overshadowed the contemporary celebration of him as a leader. Cassius Dio captures the enthusiasm of the time, noting that Verus gloried in the victories achieved under his watch and, for a fleeting moment, reached the zenith of good fortune.

“Vologaesus, it seems, had begun the war by hemming in on all sides the Roman legion under Severianus that was stationed at Elegeia, a place in Armenia, and then shooting down and destroying the whole force, leaders and all; and he was now advancing, powerful and formidable, against the cities of Syria.

Lucius, accordingly, went to Antioch and collected a large body of troops; then, keeping the best of the leaders under his personal command, he took up his own headquarters in the city, where he made all the dispositions and assembled the supplies for the war, while he entrusted the armies to Cassius.

The latter made a noble stand against the attack of Vologaesus, and finally, when the king was deserted by his allies and began to retire, he pursued him as far as Seleucia and Ctesiphon, destroying Seleucia by fire and razing to the ground the palace of Vologaesus at Ctesiphon.

In returning, he lost a great many of his soldiers through famine and disease, yet he got back to Syria with the survivors.

Lucius gloried in these exploits and took great pride in them, yet his extreme good fortune did him no good; for he is said to have engaged in a plot later against his father-in‑law Marcus and to have perished by poison before he could carry out any of his plans.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History

The Near East offers tangible evidence of Verus' prominence during and after the Parthian War. Inscriptions and monuments highlight the admiration he commanded. At Dura-Europos, an inscription testifies to a statue erected in his honor by a local citizen, Aurelius Heliodorus, reflecting regional esteem for the emperor.

Similarly, a bilingual inscription from Ruwwafa in the Hijaz records the foundation of a temple for the imperial cult under the governor Q. Antistius Adventus. This inscription, like others from Palmyra and Petra, emphasizes the widespread acknowledgment of Verus' role in the empire’s eastern frontier.

Petra, a city steeped in imperial significance, further reveals the esteem held for Verus. Archaeological discoveries include inscriptions commemorating him and his father, Aelius Caesar, alongside monumental dedications. These findings illustrate the deep connections between his leadership and the region's civic and religious life, where imperial cult worship served as a unifying force.

The campaign also brought unintended consequences. The soldiers returning from the East carried with them the Antonine Plague, which ravaged the empire, including Italy, where Verus ultimately succumbed to an apoplectic seizure in AD 168 or early 169. His death marked a turning point for the Near East, where his trusted general Avidius Cassius assumed extended command. Cassius, a native of Syria and a skilled administrator, would later rebel against Marcus Aurelius, leveraging his ties to the region.

The revolt tarnished Verus’ posthumous reputation, as his association with Cassius' rise and subsequent betrayal became a focal point for historical criticism.

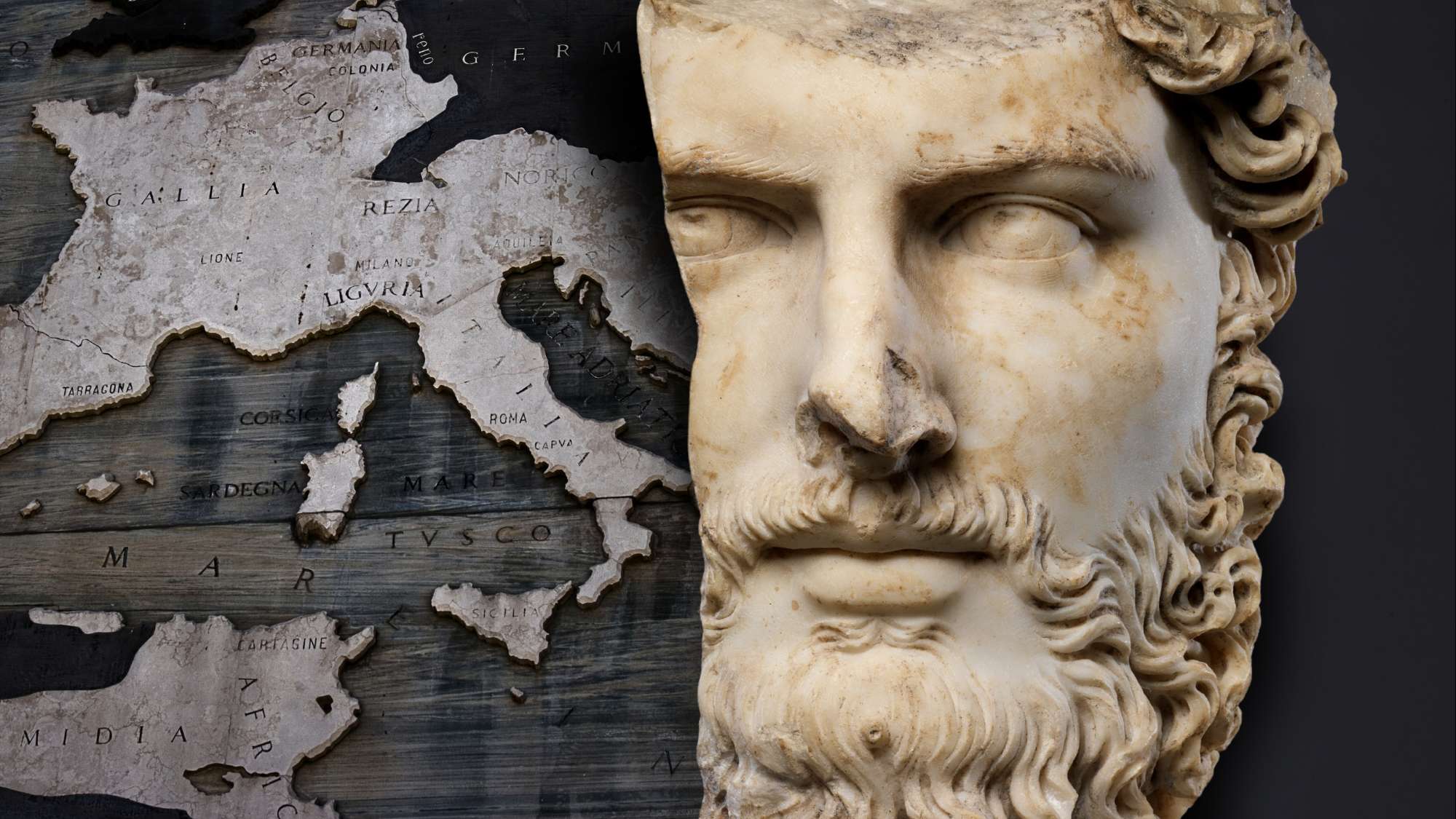

A fragmented marble bust of Lucius Verus from the side. Credits: The MET Museum, CC0 1.0

While his image has often been marred by accounts of indulgence and excess, the evidence from the Near East paints a more nuanced picture. His role in fostering loyalty and securing Roman dominance in the region was celebrated during his lifetime, as reflected in inscriptions and local monuments.

Yet, this legacy was short-lived. The rebellion of Avidius Cassius and the ravages of the plague overshadowed his achievements, leaving his memory to be shaped by later sensationalist biographers rather than contemporary acclaim.

In examining the historical record, it becomes evident that Lucius Verus' contributions to the Roman Empire were far more substantial than often acknowledged. His campaigns and their aftermath highlight the complexities of imperial rule, where success on the battlefield could be overshadowed by political intrigue and unforeseen calamities. (Lucius Verus in the Near East, by Glen W. Bowersock)

A Complex Legacy of Power, Politics, and Perception

T. D. Barnes, in his work "Hadrian and Lucius Verus" explores Hadrian’s succession plans and their connection to Lucius Verus, focusing on dynastic politics and historiographical interpretations.

It critiques the reliability of sources like the Historia Augusta, especially the Vita Veri, as a historical resource. The analysis seeks to understand Verus’s life and reign, particularly his role in Hadrian’s plans and the broader Antonine dynasty.

As already mentioned, Lucius Verus, co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius, remains one of the most enigmatic figures of the Roman Empire. His reign, often overshadowed by the philosophical legacy of his adoptive brother, Marcus Aurelius, was marked by military triumphs, dynastic politics, and the challenges of historical representation.

While often portrayed as a figure of indulgence and lesser stature, Lucius Verus played a crucial role in the Antonine dynasty and the defense of the Roman East.

Portrait of Lucius Verus as Frater Arvalis in the Louvre. Credits: Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5

The Road to Power: Hadrian’s Succession Plans

Lucius Verus’s path to imperial power was shaped long before his reign, under the careful planning of Emperor Hadrian. In an attempt to secure the succession, Hadrian adopted Lucius Ceionius Commodus (Verus’s father) as his heir. After Commodus’s untimely death, Hadrian chose Antoninus Pius, on the condition that Antoninus would adopt both Marcus Aurelius and the young Lucius Verus.

This strategic move ensured a seamless transition of power and solidified the Antonine dynasty. Although Hadrian originally hoped for the young Marcus Aurelius to succeed him, he recognized that Marcus was too young at the time.

Instead, he selected the elderly and widely respected Antoninus Pius as his successor. Many perceived Antoninus as a harmless interim ruler until Marcus was old enough to take the throne. To establish a clear line of succession, Hadrian made it a condition of Antoninus's adoption that he also adopt both Marcus, his nephew, and Lucius, the son of Aelius.

From that point forward, Lucius became known as Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus, although he would later drop "Commodus" and adopt the name "Verus" after ascending to power.

A closeup on the statue of co-Emperor Lucius Verus, in the body of an athlete, holding a statuette of Nike in his hand. Credits: Justus Hayes, CC BY 2.0

Lucius was not a newcomer to Roman politics. Before sharing the throne, he served as quaestor in 153 CE and as consul in both 154 and 161 CE, with the latter term shared alongside Marcus. In March 161 CE, following the 23-year reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius ascended to the imperial throne, taking the titles of Augustus and Pontifex Maximus.

Honoring his adopted father's wishes, Marcus petitioned the Roman Senate to elevate his adoptive brother, as co-emperor. Lucius was granted tribunician powers and the titles of Caesar and Augustus. Under this arrangement, Lucius Verus became an integral part of a broader dynastic strategy, which elevated him as co-emperor in 161 CE, alongside Marcus Aurelius.

Antoninus had left the empire in a strong position, with flourishing trade, thriving commerce, and a financial surplus due to his prudent fiscal management. However, the joint reign of the two adoptive siblings marked a sharp contrast, as it was characterized by nearly continuous warfare in both the north and east, as well as the devastating plague that swept across the empire.

Beyond their political ties through adoption, marriage further solidified their positions. Marcus divorced his first wife to marry Faustina the Younger, Antoninus's daughter, while Lucius married Marcus's daughter, Annia Aurelius Galeria Lucilla, in a ceremony at Ephesus in 164 CE. Cassius Dio, in his Roman History, remarked on their era, highlighting the events and challenges they faced.

“Marcus Antoninus, the philosopher, upon obtaining the throne at the death of Antoninus, his adoptive father, had immediately taken to share his power Lucius Verus, the son of Lucius Commodus.

For he was frail in body himself and devoted the greater part of his time to letters.

Indeed it is reported that even when he was emperor he showed no shame or hesitation about resorting to a teacher, but became a pupil of Sextus, the Boeotian philosopher, and did not hesitate to attend the lectures of Hermogenes on rhetoric; but he was most inclined to the doctrines of the Stoic school.

Lucius, on the other hand, was a vigorous man of younger years and better suited for military enterprises.

Therefore Marcus made him his son-in‑law by marrying him to his daughter Lucilla and sent him to conduct the war against the Parthians.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History

A Shared Reign: The Challenges of Co-Rule

Despite contemporary and later depictions of Verus as indulgent and frivolous, his leadership in the Parthian War was marked by significant victories. Under his nominal command, as already mentioned, Roman forces captured the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon, burned the royal palace, and sacked Seleucia. These achievements extended Roman influence in the Near East and underscored Verus’s contributions to imperial defense.

Historical Perception: Frivolity or Strategy?

Lucius’ reputation has long been shaped by sources such as Cassius Dio, the Historia Augusta, and Lucian, many of which emphasize his indulgent lifestyle and lack of personal involvement in military campaigns. However, recent scholarship suggests a more nuanced perspective.

The victories in the Parthian War brought immense prestige to him, as evidenced by inscriptions and monuments celebrating his triumphs across the Eastern provinces (notable examples earlier in this article). These commemorations reflect the esteem in which he was held during and immediately after his campaigns, countering the narrative of his supposed ineffectiveness.

The Role of Propaganda: The Antonine Image

Like all Roman emperors, Verus relied heavily on propaganda to shape his image. The Constitutio Antoniniana, a decree issued in 212 CE, and other imperial proclamations promoted themes of unity, piety, and military valor.

His portraiture also evolved, presenting him with a cropped, militaristic hairstyle and a furrowed brow—visual cues of virtus (manly excellence) and stoic endurance.

Roman Marble Bust of Lucius Verus, Co-Emperor with Marcus Aurelius. Credits: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0

This propaganda effort sought to counteract criticisms and ensure his legacy as a capable leader and defender of the empire. However, his death in 169 CE from an apoplectic seizure, coupled with the outbreak of the devastating plague brought back by his troops, complicated his historical legacy.

The Fallout: A Legacy in Question

The untimely death of Lucius Verus marked the beginning of a turbulent period for the Roman Empire. The literary tradition that followed largely marginalized him, focusing instead on his perceived vices and relegating his achievements to the background.

Emperors and historians of later centuries preferred to highlight other military successes while leaving Verus to the records of sensationalist biography. Lucius continues to remain a figure caught between historical reality and narrative distortion.

While ancient and modern sources often depict him as a foil to Marcus Aurelius’s intellectualism, his military achievements, strategic significance, and role in the Antonine dynasty suggest a more complex legacy. By reevaluating the evidence, including inscriptions, coinage, and contemporary accounts, a fuller picture of him emerges—one of an emperor who, despite his flaws, left an indelible mark on Roman history.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: