Before Mondays Existed, Rome Had This

Before weeks were named and calendars fixed, Romans lived by a different rhythm. Every eighth day, markets reshaped movement, trade, and public life, revealing how time, economy, religion, and power were woven together in the Roman world.

Rome’s life did not unfold in a smooth, uninterrupted flow. It moved in intervals—predictable, recurring, and quietly authoritative. Certain days pulled people into the city; others sent them back to their fields, workshops, and obligations. This rhythm shaped when goods were sold, when news travelled, when crowds gathered, and when the state deliberately stood still. Long before the familiar week divided time into neat units, Romans organised their world according to a different cycle—one so embedded in daily life that it governed movement, labour, and expectation without ever needing explanation.

Why Rome Needed Periodic Market-Days

No aspect of the Roman economy depended more heavily on routine than local exchange. The movement of goods within short distances—often no more than a day’s walk—formed the backbone of economic life across the Empire. Although rarely visible in literary sources and difficult to trace archaeologically, this circulation accounted for the majority of commercial activity.

It sustained rural communities, connected villages to nearby towns, and ensured the flow of necessities that neither households nor estates could reliably produce on their own.

Large areas of the countryside were too sparsely populated to support permanent commercial centres. In such regions, periodic gatherings emerged as a practical solution. Farmers assembled at known locations on fixed days to sell surplus produce and obtain items unavailable through subsistence farming alone.

These temporary markets left little physical trace, yet their presence is implied by scattered coin finds, pottery fragments, and the clustering of minor objects at crossroads and open sites. For rural populations, such occasions provided modest dietary variety, access to tools and materials such as iron and salt, and occasional minor luxuries.

In some agricultural regions, local exchange was not merely useful but indispensable. Areas specialising in a single crop—olive cultivation in parts of Spain, Syria, or North Africa—could not sustain life without regular opportunities to trade. Here, market-days ensured survival. Landowners sometimes facilitated exchange by opening their estates on fixed dates, allowing tenants and traders to gather within villa courtyards equipped with storage spaces, stables, and shelter. Elsewhere, fairs developed on open ground, gradually acquiring a degree of permanence through repeated use.

These gatherings were not informal or spontaneous. The right to establish a market carried legal and economic weight and required official approval. Market-days generated tolls, attracted crowds, and redirected trade flows, sometimes to the disadvantage of neighbouring centres. For this reason, Roman authorities closely regulated their creation and timing, seeking to prevent excessive competition and to preserve order within local commercial networks.

Markets also gravitated toward existing settlements. Roadside clusters of workshops and small shops functioned as points of manufacture and retail, while villages with only a few hundred inhabitants could host surprisingly large crowds on designated days. Epigraphic evidence reveals itinerant traders moving from one market to another, carefully coordinating their routes to coincide with scheduled gatherings.

The success of these circuits depended on predictable timing. Markets were arranged so that traders could move efficiently between them without overlap, ensuring that goods, people, and profit circulated continuously rather than concentrating in a single location.

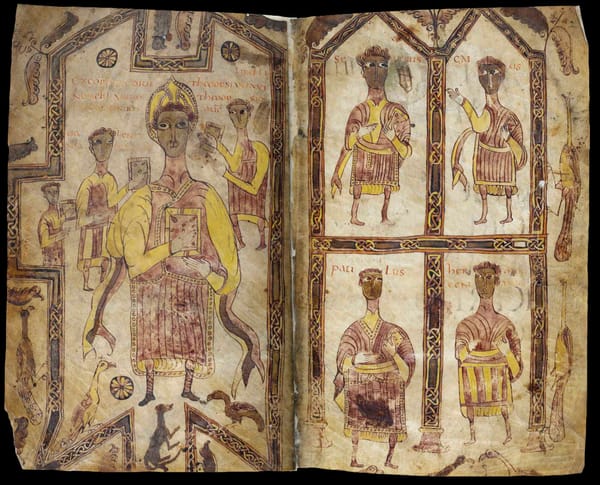

Religious observance further reinforced this system. Festivals and sacred days drew crowds to temples and shrines, creating ideal conditions for exchange. Across both eastern and western provinces, holy days regularly doubled as market-days. Deities associated with trade were thanked for profits earned at these gatherings, while sanctuaries themselves became commercial hubs, combining worship, sales, accommodation, and storage within the same precincts. In this way, economic activity, ritual practice, and social life converged.

Taken together, these patterns reveal a world in which exchange depended not on constant access to markets, but on carefully timed concentration. Periodic market-days brought together rural producers, urban consumers, and itinerant merchants in numbers large enough to make trade viable. Without such rhythm, much of the Roman economy—especially beyond major cities—could not function at all. ("Market-Days in the Roman Empire" by Ramsay MacMullen)

When the Market Day Had to Move

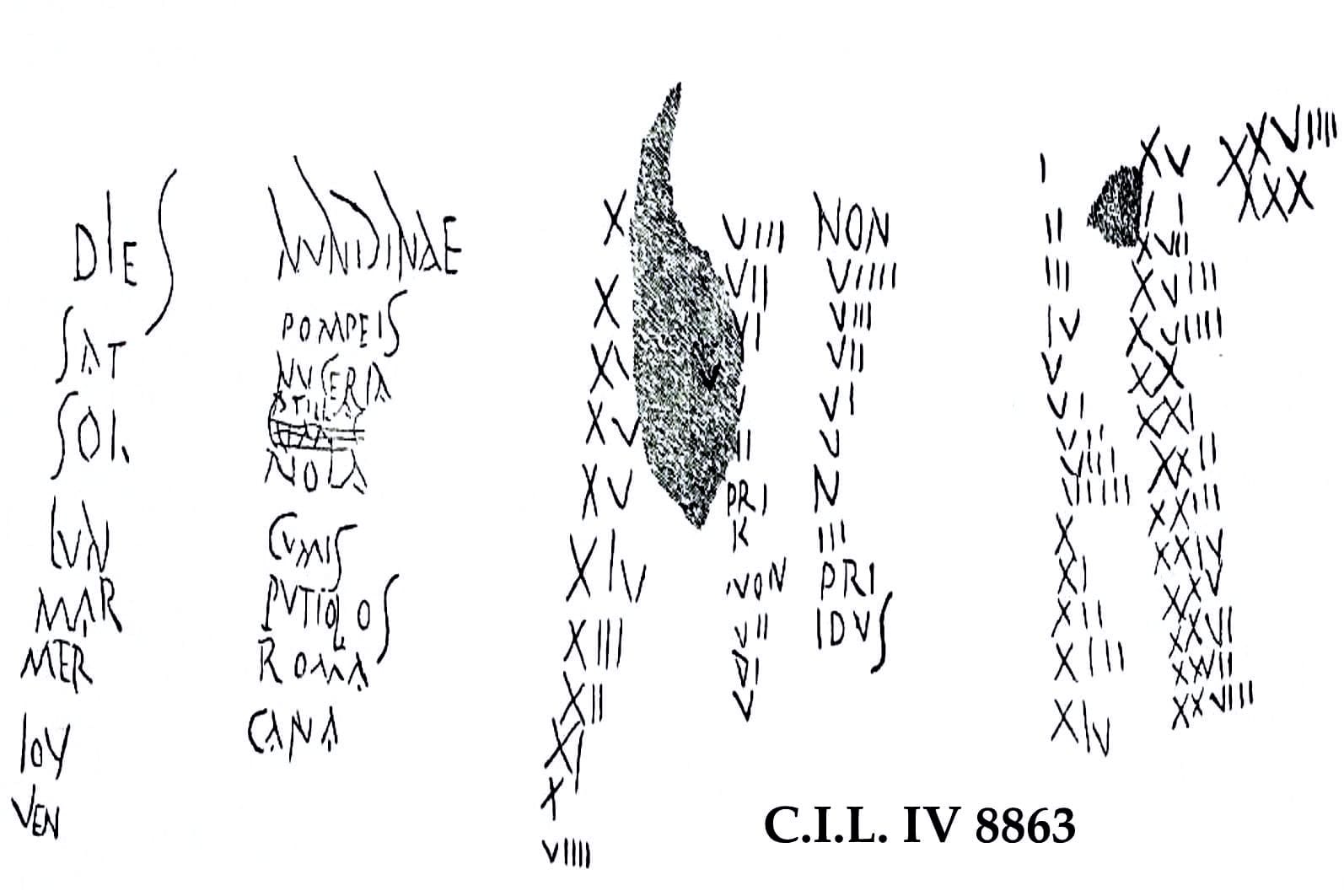

The eight-day market cycle was designed to be regular, but it was not untouchable. Under certain circumstances, Roman authorities were willing to intervene—especially when religious concerns came into play. Ancient writers make clear that market-days were not adjusted lightly. When they were, it was usually to avoid an ill-omened coincidence rather than for administrative convenience.

One recurring problem concerned leap years. The Roman calendar periodically inserted an extra day, creating a brief disruption in the normal rhythm of time. This raised a practical question: should the market cycle absorb the extra day, or should it skip it? The answer mattered, because the nundinae were part of a wider network of markets held in different towns on different days. A change in Rome could ripple outward, affecting traders, schedules, and expectations far beyond the city itself.

Ancient evidence suggests that Roman officials did not aim to “correct” the cycle mathematically. Instead, they acted pragmatically. When a market-day threatened to fall on a date regarded as religiously dangerous, it could be shifted. Cassius Dio reports such a case, noting that a Roman market-day was moved explicitly because of religious rites. This was not a technical correction but a deliberate avoidance.

The key religious factor appears to have been the Regifugium, a festival associated with the symbolic withdrawal of royal authority and widely regarded as ill-omened. Over time, the first day of the leap-year pair—the biduum—came to inherit this negative character. Holding a market on that day was increasingly seen as inappropriate. Rather than abolishing the market or abandoning the cycle, officials simply moved the market-day to the following day in affected years.

This solution reveals something important about how Romans understood time. The nundinae were expected to be predictable, but not at the expense of religious order. When calendar structure and ritual observance came into conflict, ritual took precedence. The market could wait a day. The omen could not. ("The Imperial Nundinal Cycle" by Chris Bennett)

If calendar rules shaped when markets could take place, individual decisions determined where they were held—and who controlled them.

A Senator’s Private Market and a City’s Objection

Two letters in the fifth book of Pliny the Younger’s Letters preserve a dispute that began as a request for a rural market and escalated into a question of status and leverage. As Pliny puts it:

“It was a small matter, but the beginning of a matter that was not”

The issue was this: L. Bellicius Sollers, an ex-praetor, applied to the Senate for permission to establish nundinae on one of his estates. Vicetia, a nearby North-Italian town, sent deputies to object. The case was initially adjourned, and Vicetia retained professional legal help—fees that Pliny reports as reaching 10,000 sesterces.

When proceedings resumed, the imbalance between a municipal delegation and a senator became harder to ignore. Vicetia’s advocate withdrew, later claiming he had been warned that he was no longer facing an ordinary matter. Friends had reminded him that Sollers:

“was no longer contending about a market, but rather about his influence, reputation and honour”

The Senate allowed the advocate to avoid the case on the condition that he repay the fees, and the wider fallout pushed the Senate toward tightening rules around fee-taking advocates—an aspect that interested Pliny particularly.

Behind the legal drama sits a practical question: why would a powerful landowner want a periodic market on private property, and why would a town fight it? A rural nundinae could make exchange easier for the surrounding population, reducing the need to travel to the city for regular buying and selling.

At the same time, such a market could strengthen the landlord’s local standing and deepen dependence on the estate, especially in landscapes dominated by tenant holdings rather than tightly controlled, self-sufficient villa production.

For Vicetia, the risk was not sentimental. A nearby rural market threatened to redirect people, produce, and transactions away from the city’s own market. That could mean weaker supply in the urban marketplace, higher prices, and the kind of tension municipal authorities were expected to avoid. It also threatened municipal income drawn from market activity—through taxes and other levies tied to circulation and exchange.

Comparable evidence from elsewhere shows that authorities paid close attention to whether a newly requested market would “harm” existing schedules or reduce revenues “either for the city or for the most sacred treasury.”

The case also illustrates who held the decisive power. Applications for the ius nundinarum in Italy were handled at the centre, and the applicant in this case was not only a senator but one with substantial influence and support. A later assessment quoted in the chapter captures how uneven such contests could be:

“the senator could not help winning such an unfair contest”

What emerges is a picture of the nundinae as more than a convenient meeting day. A market could reshape local circuits of supply, touch municipal finances, and expose the limits of urban leverage when elite private interest was involved. ("The nundinae of L. Bellicius Sollers," by L. de Ligt)

Living Inside the Roman Calendar

Time is not just something that passes; it is something people learn to recognise, anticipate, and organise their lives around. Some days stand out, others fade into the background, but all of them begin somewhere, and together they form repeating sequences that give structure to human activity.

Without beginnings, time would be shapeless; without repetition, it would be impossible to plan. What people call “time” is, in practice, a pattern.

For the Romans, this pattern was neither simple nor uniform. Their year was shaped by overlapping rhythms: fixed religious dates, recurring festivals, and the steady return of the market day every eighth day, regardless of how months were arranged. These cycles did not always align neatly, but that was precisely what gave Roman time its texture. Regularity offered reassurance, while irregular interruptions prevented life from becoming monotonous. The calendar balanced both.

Nature itself provided some of this structure. The alternation of day and night, the movement of the sun and moon, and the turning of the seasons offered obvious points of reference. But human society added its own rhythms. Markets were held at fixed intervals; festivals marked moments of collective attention; legal and religious restrictions shaped what could or could not be done on certain days. In this way, social life imposed its own order on time.

How early this system took shape is impossible to say. By the late Republic, Romans themselves no longer remembered its origins. Even the antiquarians of the first century BC were already dealing with traditions whose beginnings lay beyond reach.

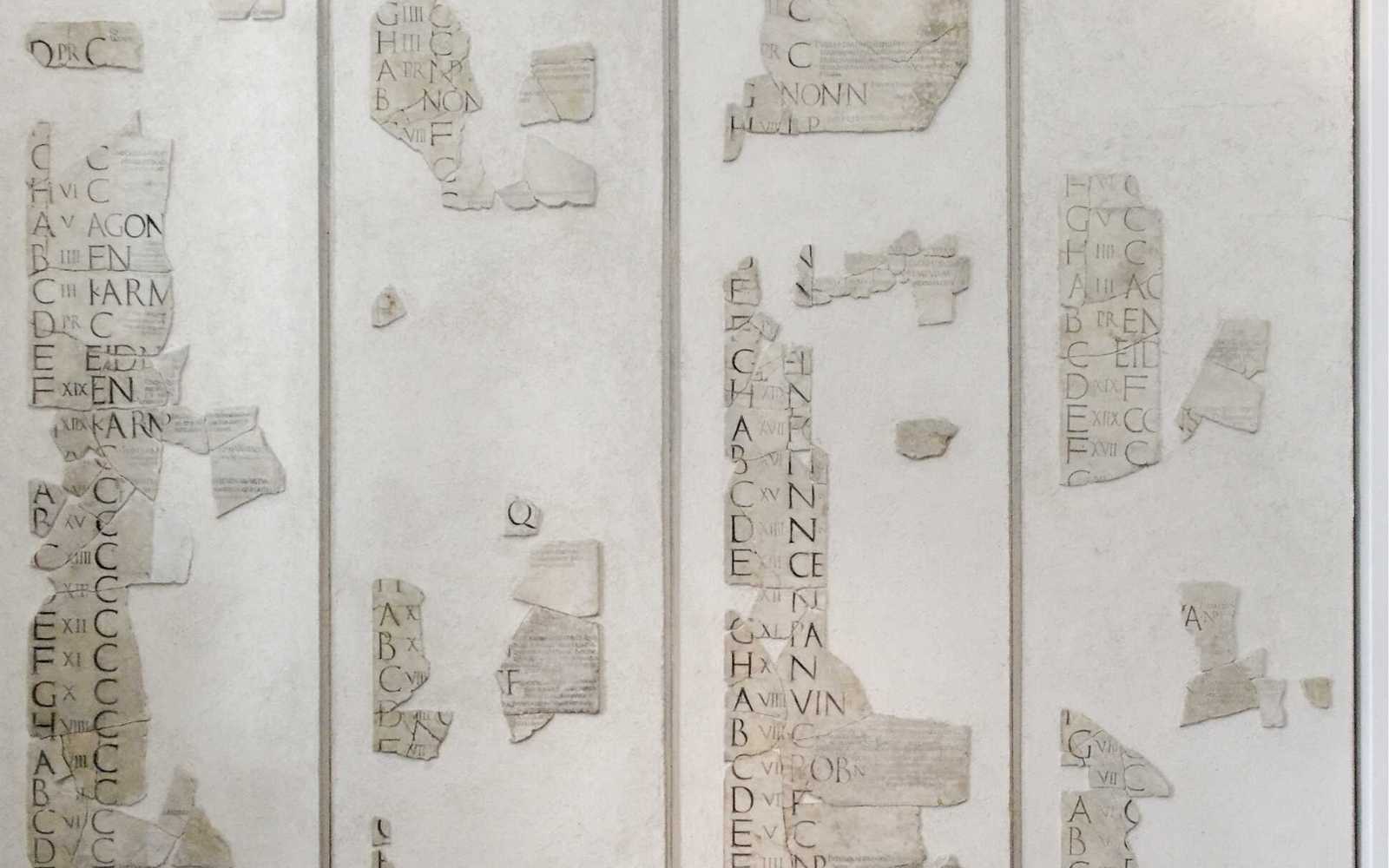

What we know comes largely from later writers who gathered fragments of earlier learning, sometimes faithfully, sometimes uncritically. Yet despite the uncertainty of the details, it is clear that both monthly religious dates and the regular market cycle were already established by the early Republic.

In its earliest form, this calendar was probably simple and spare. Over time, it accumulated additional layers of meaning and practice. Under the Empire, a new rhythm began to appear alongside the old one — the seven-day week — which developed independently and eventually came to dominate everyday life. But before that transformation, Romans lived within an older framework, one that did not name every day individually.

In the early Republic, only certain days were singled out by name. Some annual festivals were fixed and memorable, while each month was anchored by three key points: the Kalends, the Nones, and the Ides. Rather than counting days forward from the past, Romans thought ahead toward the next significant moment. A date was not “the 10th” but “four days before the Ides.” Time was defined by what was coming, not what had already passed.

This way of reckoning made sense in a world where months were once tied to the moon. The Kalends likely marked the appearance of the new moon, while the Ides were associated with the full moon. When the calendar was later adjusted to follow the solar year, these connections were lost, but the structure remained. The names endured even after their original meaning faded.

What mattered was not astronomical precision but shared expectation. Certain days were sacred, others unsuitable for business, and still others associated with ill-omen. These distinctions were not obvious to everyone. For a long time, knowledge of which days were favourable or forbidden was controlled by priestly elites. Only when calendars were made public did this information become accessible to the wider population.

Alongside these religious markers ran the most dependable rhythm of all: the market day. Every eighth day, work paused, families gathered, and people travelled to town to trade, exchange news, and take part in public life. This cycle cut across months and festivals alike. It was the one element of Roman time that remained steady no matter how the calendar shifted.

Together, these overlapping patterns — religious dates, market days, and later the planetary week — formed the lived experience of time in Rome. They shaped habits, expectations, and social behaviour long before they became objects of scholarly calculation.

Long after the old system faded, traces of it survived in memory, custom, and the structure of later calendars. What remained most enduring was not the Roman way of counting days, but the human need for time to have shape, rhythm, and meaning.

For centuries, the nundinae structured Roman life more reliably than months or numbered dates. They organised exchange, regulated movement, and shaped when people gathered, spoke, and waited. Long before Mondays existed, it was the market-day that gave Roman time its most familiar rhythm.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: