Analysis of the World of Virgil: Eclogues, Georgics, and the Aeneid

Virgil transformed Rome’s past into prophecy and poetry into conscience. From the shepherds of Mantua to the heroes of empire, his voice became the soul of Rome’s Golden Age—and the eternal guide of Western imagination.

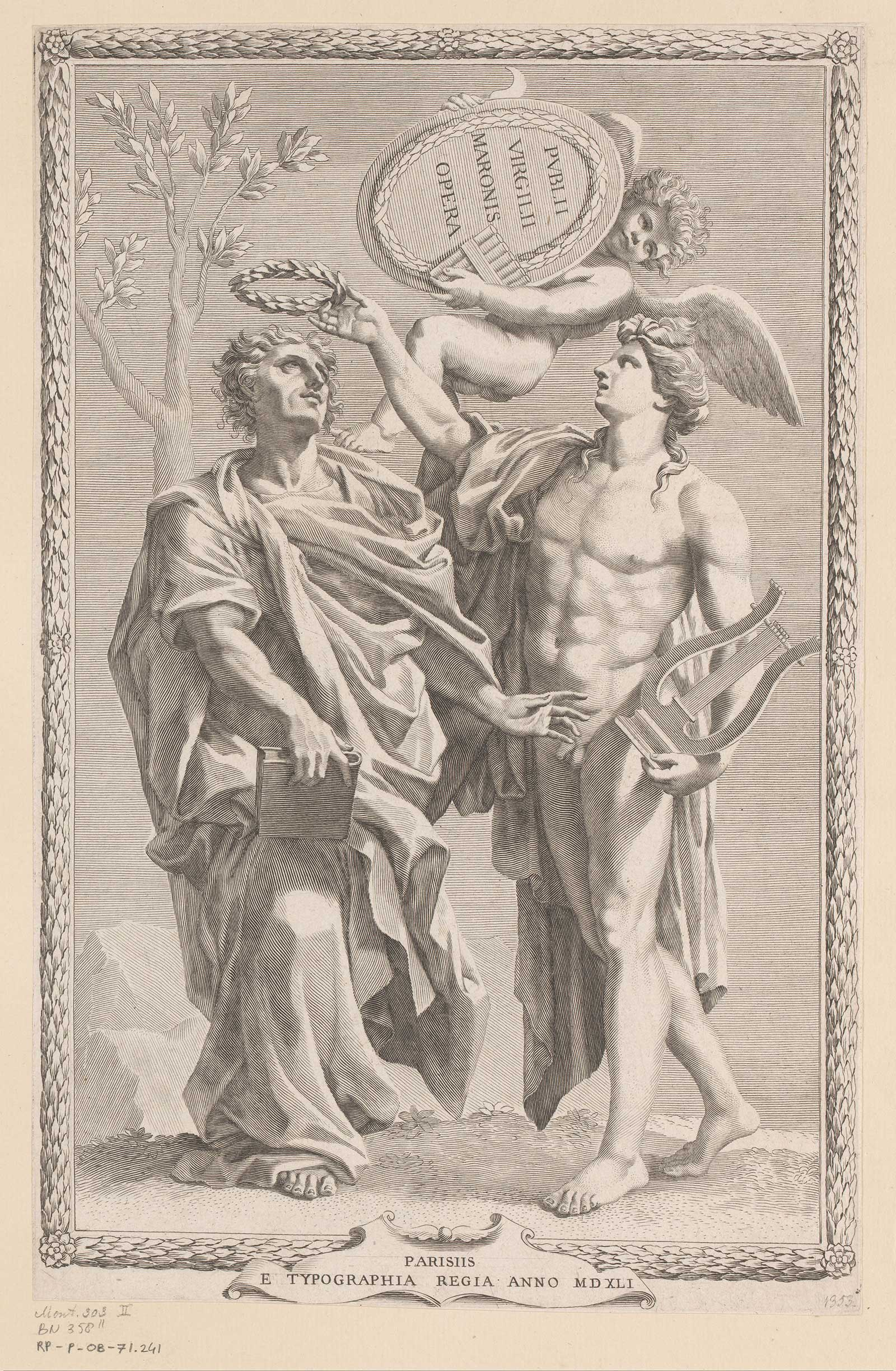

No poet captured the Roman soul more completely than Publius Vergilius Maro. Born in 70 BCE near Mantua, Virgil rose from provincial obscurity to become the voice of an empire and the conscience of its new age. Through the Eclogues, Georgics, and above all the Aeneid, he transformed Rome’s myths into a vision of destiny — a world where poetry, politics, and prophecy converged.

Under Augustus, his verses became the empire’s mirror: celebrating peace after civil war, sanctifying power through divine lineage, and giving Rome a story it would tell for a thousand years. Long after his death, the poet himself passed into legend — revered as a prophet of Christian truth, a sage who spoke in riddles of salvation, and a guide through the underworld of imagination. From the fields of Mantua to the hearts of medieval scholars, Virgil remained what he had always been: the poet who taught Rome to dream of eternity.

Virgil’s Poetic Universe: The Soul of Rome in Verse and Vision

Virgil stands at the hinge of Roman memory and imperial purpose, shaping a poetry where private sorrow meets public destiny. Across the Eclogues, Georgics, and Aeneid, his voice moves from fragile pastoral hope to national vocation, binding aesthetic craft to the ethics of rule. The Aeneid opens under the sign of burden—

“Tantae molis erat Romanam condere gentem” (“So vast was the task of founding the Roman race,” )

and never lets the reader forget the price of greatness. Hardship is transfigured by remembrance—

“Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit” (“Perhaps one day it will be a joy to recall even these hardships,” )

yet compassion remains the poem’s pulse:

“Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt” (“There are tears for things, and mortal sorrows touch the heart,” ).

The poem turns on duty (pietas) and fate, not as abstractions but as choices made in extremis. In Book 7, history pivots—

“tanto cardine rerum” (“at such a hinge of the world,”)

from wandering to war, as Italy becomes both promised land and proving ground. Scenes of pity interrupt vengeance: in the fall of Lausus, filial courage arrests the victor’s rage—

“terra sublevat ipsum” (“the earth itself lifts him up,”)

a moment where humanity briefly outshines triumph. Yet the epic refuses consolation: it ends with Aeneas’ killing of Turnus, duty hardening into necessity, and mercy failing at the sight of the spoils.

Earlier works foreshadow this ethic. The Eclogues stage loss and longing in a fractured countryside, pastoral song haunted by dispossession. The Georgics turns toil into wisdom, teaching that order is wrested from resistance—farming as a school of endurance, ritual, and restraint. Taken together, the three works sketch a Roman pedagogy: cultivate the land, govern desire, remember the dead, and bear the yoke of fate without surrendering pity.

Virgil’s achievement is not propaganda but tragedy tempered by hope. Destiny advances, yet the poet lets suffering speak. Rome’s founding is necessary; it is also grievous. Between fate’s summons and a heart that “weeps for things,” Virgil composes an empire’s conscience—measured, grave, and unforgettable. (The Poetic Achievement of Virgil, by Viktor Pöschl)

The Book of Virgil: A Circle Without End

Virgil’s three major works—the Eclogues, the Georgics, and the Aeneid—have often been read as the steps of a poet’s ascent: from the quiet of the countryside to the labor of the fields, and finally to the epic destiny of empire. Yet within these poems lies another design: a continuous circle of reflection and return, in which beginnings and endings echo one another, and the poet’s voice never truly departs from its first note.

This circular structure is signaled by repetition and shadow. The first words of the Eclogues—

“Tityre, tu patulae recubans sub tegmine fagi” (“Tityrus, you who lie beneath the spreading beech”),

open a world of pastoral stillness—a world of rest and exile, of voices seeking shelter beneath the trees. The last line of the Aeneid—

“vitaque cum gemitu fugit indignata sub umbras” (“and with a groan, the life fled indignant to the shades,”)

closes that same world in darkness. Between those two moments, Virgil’s poetry travels from light to shadow, from song to silence, yet the cycle of utterance remains unbroken.

The poet’s career can thus be seen not as a straight path toward closure but as a self-contained book—the “Book of Virgil”—in which each work reflects and transforms the others. The Georgics looks back to the Eclogues, turning pastoral into instruction, while the Aeneid draws upon both, absorbing their imagery of land, labor, and loss. What appears as progression is in fact a spiral of recollection, a poetic cosmos turning upon itself.

Everywhere Virgil stages the tension between completion and continuation. His Eclogues end not with resolution but with song fading into distance. The Georgics concludes in turmoil, its meditation on order dissolving into images of civil war and broken peace.

The Aeneid, for all its grandeur, refuses the consolations of a final harmony. Its last word, umbra, recalls the shades that haunt every Virgilian landscape—the memory of those displaced, forgotten, or silenced in the making of order.

Through such echoes, Virgil transforms literary closure into reflection. Each poem gestures backward as much as forward, binding Rome’s story to the sorrow of its creation. The recurring word cano—“I sing”—marks this unity of voice. Whether the poet sings of shepherds, farmers, or heroes, the act of song itself becomes the thread that holds his world together.

In this way, Virgil’s poetry forms a single, self-aware whole—a circle without end. Its unity lies not in triumph but in remembrance: a vision of human endeavor shadowed by mortality, where every ending leads back to the beginning. Beneath the calm of the beech tree and the darkness of the battlefield alike, the same voice endures—singing of life’s fragility and the eternal labor of making meaning from loss. (Closure and the Book of Virgil, by Theodorakopoulos, Elena)

The Poet and His Shadow

The figure of Virgil that survives in history is both a poet and a myth. Few writers have seen their identity so thoroughly absorbed by their own creation. The story of Virgil’s life, told and retold since antiquity, became inseparable from his poetry—an extension of the same imaginative world that produced his best works.

In the centuries following his death, readers continued to shape and reshape his image, interpreting every biographical fragment through the lens of his verses. The boundary between the man and the myth blurred, until the poet himself seemed to exist as one of his own characters—an enduring voice speaking through the centuries.

The early biographies portrayed him as modest, contemplative, and deeply private. Later traditions turned that restraint into legend: a poet who disliked public fame, who left his epic unfinished, and who, at the end of his life, asked for it to be burned. That image of renunciation became one of the central myths surrounding him—a poet so devoted to perfection that he preferred silence to imperfection.

The story, whether true or not, spoke to a deeper truth about the nature of poetic creation in Rome: that art, once born, no longer belonged to its maker.

The supposed destruction of the Aeneid thus became a parable of artistic immortality. Even if the poet had wished to consign it to flames, the poem had already outlived him, carried by others who refused to let it die. The tale revealed how the author’s control over his work dissolved at the moment of death, leaving the poem to enter a new life of interpretation and appropriation.

In this sense, Virgil’s legend anticipated his own theme: the transformation of mortality into memory, the survival of voice beyond the speaker.

From early commentaries to late antique anecdotes, the poet’s life was read as allegory. The Eclogues were said to reflect his youth, the Georgics his maturity, the Aeneid his wisdom and decline—an image he himself foreshadowed in the line:

“cecini pascua rura duces,” (“I sang of pastures, fields, and leaders.”)

This triad of song became the poet’s epitaph, a summary of both his career and his transformation into a symbolic figure: shepherd, farmer, and prophet of empire.

In the centuries that followed, the line acquired mystical significance. Readers saw in it a prophecy of the world’s spiritual evolution—from the innocence of nature, through the toil of cultivation, to the governance of reason and order. Each stage mirrored both the progress of Rome and the growth of the human soul. The poet’s own life, real or imagined, became the measure of that ascent, his voice the bridge between pastoral calm and imperial destiny.

Yet the image of Virgil remained haunted. Ancient imagination did not let him rest. Stories spread that he continued to speak after death—that his spirit could be summoned for counsel, and that his tomb in Naples possessed oracular power. The poet who once guided Aeneas into the underworld became, in turn, the shade whom others sought to question.

This transformation of the author into his own ghost fulfilled the prophecy implicit in his work: that song, once uttered, endures beyond its mortal frame.

The Poet Inside the Poem

Virgil did not simply compose poetry; he inhabited it. Ancient readers perceived within his works a distinct, almost living presence—a consciousness that observed, suffered, and remembered. In his lines, the poet seemed to stand alongside his characters, guiding them and, at times, lamenting their fate.

Unlike Homer’s distant omniscience, Virgil’s voice entered his creation with unmistakable intimacy. His poetry is not the record of events but the echo of an inner experience.

This self-presence was subtle but constant. In the Eclogues, it takes the form of a hidden poet who listens more than he speaks, allowing shepherds to voice his own longing for peace and exile. The pastoral world he describes:

“Tityre, tu patulae recubans sub tegmine fagi” (“Tityrus, you who lie beneath the spreading beech”)

is both landscape and refuge, a space where poetry and memory intertwine. The apparent simplicity of these scenes conceals a tension between serenity and loss, between the safety of song and the reality of displacement.

The Georgics brings that inner voice into sharper focus. Beneath the didactic surface lies the figure of the poet-laborer, the one who works the soil of language as the farmer works the field. His instruction on crops, bees, and weather is also a meditation on endurance:

“labor omnia vicit improbus”—“relentless toil conquers all.”

Yet this statement, often read as a moral maxim, carries an undertone of resignation. The poem’s closing lament for Orpheus and Eurydice transforms agricultural labor into artistic struggle; the tiller of the earth becomes the poet who plows through loss.

In the Aeneid, that presence deepens into tragic awareness. Here the poet is both narrator and witness to the cost of empire. His voice moves between triumph and pity, urging reverence for fate yet mourning the human price of destiny. Through Aeneas’ journey, Virgil contemplates the burden of founding a new order.

The poet who once sang of shepherds and farmers now speaks for nations, but his compassion remains the same. When he writes,

“sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt”—“there are tears for things, and mortal matters touch the mind”

he reveals not only Aeneas’s grief but his own.

This blending of author and art was recognized early. Ancient critics and commentators treated Virgil’s characters as mirrors of his moral and emotional state. The Eclogues’ melancholy was linked to his withdrawal from civil conflict; the Georgics’ balance of work and faith reflected his philosophical discipline; the Aeneid’s pathos was read as his moral conscience confronting Rome’s destiny.

The poet became both creator and creation, his life absorbed into his verse until biography itself became a literary genre.

Thus emerged the tradition of the “Virgilian self”: a poetic persona whose authority derived from introspection and compassion. He was not the impersonal bard of heroic ages but a participant in the suffering he described—a voice that endured within the very world it mourned. Through this transformation, poetry became a moral act: to sing was to bear witness.

The Poet Beyond Time

Death did not silence Virgil; it only changed his audience. In the centuries that followed, his image took on the quality of prophecy. The poet who had guided Aeneas through the underworld now became a guide himself—summoned by readers, scholars, and dreamers who sought wisdom from his shade.

His tomb in Naples was said to possess mystical power; visitors left offerings as though to a divine oracle. The poet who had written of descent and return was imagined as dwelling eternally between the worlds of the living and the dead.

Ancient commentators treated his works as sacred texts. The lines of the Aeneid were opened for divination—Sortes Vergilianae—as though each verse contained a hidden command from fate. To consult the poet was to ask the gods. His words, already invested with destiny, now functioned as prophecy: the Aeneid became not only Rome’s epic but its scripture.

Even his supposed desire to destroy his poem took on a symbolic meaning. The story that he wished the Aeneid burned before his death was retold as a parable of creative surrender: art transcending the will of its maker. Once released into the world, the poem ceased to belong to the poet. The flames he invoked became metaphors for purification—the necessary destruction through which poetry attains immortality.

The legend of the speaking tomb deepened through the Middle Ages. Scholars wrote of the poet’s spirit appearing to the learned, reciting verses, or giving counsel. Some claimed that he had mastered forbidden knowledge, transforming from poet into magician.

Others, more devout, imagined him as a pagan saint, the prophet who unknowingly announced the coming of a new age. A line from the Eclogue,

“iam redit et Virgo, redeunt Saturnia regna”—“the Virgin returns, the reign of Saturn returns”

was read as a prophecy of Christian salvation. Through such reinterpretations, Virgil crossed the threshold from antiquity into eternity.

The poet’s own works had already foretold this paradox of survival. In the Aeneid, Anchises shows Aeneas the souls of future Romans waiting to be reborn. Among them is the poet himself, though unspoken—a silent witness to his own destiny. The world he imagined became the one he inhabited after death: a landscape of memory, order, and longing where his words continued to move like living souls.

In this continuity between life and legacy, Virgil achieved what his heroes could not: peace through endurance. His poetry became Rome’s conscience, its lament, and its dream of permanence. To read him was to enter a dialogue not only with empire and history, but with the enduring voice of art itself.

He was the poet who sang of shepherds, fields, and leaders—cecini pascua rura duces—but also the poet who made song a bridge between mortality and meaning. His shade, in the end, remained among his readers—speaking still, guiding still, the eternal companion of every soul seeking passage through the underworld of words. (Virgil: Reception and the Myth of Biography, by Andrew Laird)

The Making of the Virgilian Myth

When Virgil died in 19 BCE, he left behind more than a body of poetry—he left a life ready to be reimagined. Within a generation, the Romans began shaping the poet’s image through a series of Vitae, or “Lives,” which blurred the lines between history and interpretation.

These ancient biographies, drawing from the traditions of Suetonius and Donatus, were not neutral records of fact but mirrors reflecting how later readers wished to see him: a man whose character and destiny were inseparable from his verse.

For the ancients, biography was never a matter of detached storytelling. To write a poet’s life was to interpret his work. The Vitae turned Virgil’s poems into evidence of his personality and moral character. Details of his supposed modesty, melancholy, or prophetic vision were drawn directly from the tone of his works.

Even the most intimate episodes—the retreat to Naples, his desire to burn the Aeneid, his reverence for Augustus—became part of a symbolic narrative, illustrating not the man as he was, but the poet Rome needed him to be.

In this retelling, Virgil became a figure of almost sacred dignity. His life was read as a moral parable, his poetry as revelation. The Eclogues showed the purity of rural contemplation; the Georgics, the virtue of labor and order; the Aeneid, the fulfillment of divine mission.

Ancient readers saw in this progression the unfolding of a soul aligned with Rome’s destiny. His birth near Mantua, his education at Cremona and Naples, and his eventual presence at Augustus’ court were arranged into a pattern of providence, each step preparing him for the composition of the empire’s sacred epic.

The biographers’ art was to make poetry into proof. The story of Virgil’s frail health, his shyness, and his reluctance to appear in public echoed the humility and introspection of his lines. The accounts of his journey to Greece and his wish to destroy the unfinished Aeneid were transformed into symbols of artistic conscience and divine restraint—the poet who reached too close to perfection, aware that his work touched the limits of the mortal and the eternal.

Over time, this interplay between text and life gave rise to a new kind of myth. The poet himself became part of the cultural memory of Rome: half man, half allegory, embodying wisdom, purity, and prophetic insight. His tomb at Naples, whether real or imagined, was treated as a shrine. Pilgrims came not to honor a writer but to commune with the spirit of empire’s conscience.

The Vitae thus created more than a biography—they forged a national ancestor. In their hands, Virgil became the measure of poetic and moral authority, the “Roman Homer” whose voice outlived his mortal frame. Through the careful fusion of fact and interpretation, they ensured that every line he wrote was read as self-revelation, every silence as a mystery, and every act as the working of fate.

This is how the Romans themselves canonized their poet. Not by divine decree, but by commentary disguised as life—by transforming Virgil from author to archetype, from man of Mantua to eternal witness of Rome’s destiny.

The Poet Reimagined: How Rome Turned Virgil’s Life into Legacy

Ancient “Lives” of Virgil were never neutral backgrounds to the poems—they functioned as interpretations in narrative form. By selecting, arranging, and sometimes inventing episodes, the biographical tradition taught readers how to read his epics.

Life stories became glosses: the shy, austere persona validated the poems’ moral gravity; the retreat to Naples authorized the image of a contemplative poet; the tale of the journey to Greece and the wish to burn the unfinished epic framed the Aeneid as a work that tests the limits of human craft and divine purpose.

These biographies follow recognizable scripts. Education at Cremona and Naples signals philosophical formation; proximity to Maecenas and Augustus marks poetic vocation within the new political order; fragile health and public reserve confirm an ideal of dignified restraint.

Each motif is a hermeneutic cue. Rustic origins justify the pastoral voice of the Eclogues; the discipline and technical exactness ascribed to the poet underwrite the agricultural ethic of the Georgics; the narrative of imperial patronage and pious obedience aligns the Aeneid with Rome’s providential history.

The Vitae also read the poems back into the life. Scenes and lines become evidence: laments and elegiac tones support a portrait of melancholy; prayers and prodigies substantiate a reputation for quasi-prophetic insight. The poet’s supposed reluctance to publish, or desire to destroy the epic, is turned into a moral exemplum of artistic conscience—suggesting that the poem’s authority does not rest on flattery but on severity of judgment.

In this way, biography polices interpretation, steering readers away from seeing the Aeneid as mere encomium and toward a vision of epic as ethical trial.

Over time, the tradition hardens into a canon of anecdotes that do double duty as reading instructions. The “Mantuan” identity locates the poet at a Roman periphery that can speak for the whole; the Naples circle joins him to Greek learning and philosophical calm; the final days at Brundisium and the charge to leave the epic unfinished encourage reverence for textual difficulty—an invitation to treat broken edges and interpretive knots as purposeful.

Even the tomb becomes commentary: a shrine that endorses pilgrimage-style reading, where the life is approached through the poem and the poem through the life.

What emerges is a feedback loop: poem → life → poem. Biography confers ethical authority on the text; the text, in turn, ratifies the life-story. This is how the poet becomes an institution. The result is not a dossier of facts but a framework for reception—a way of ensuring that each generation encounters the Aeneid as both national scripture and human meditation on loss, duty, and the costs of empire.

In the ancient classroom, to learn the “life” was to learn how to listen: to hear pastoral modesty without sentimentality, agricultural labor without idyll, and epic grandeur shadowed by pity. Read this way, the Vitae are less about who the poet “really was” than about what the poems must mean. They fix the poet as exemplar—measured, scrupulous, almost priestly—so that the verses can be read as Rome’s conscience.

The aftereffect is powerful: even now, readers approach the Aeneid predisposed to treat uncertainty, silences, and grief as deliberate signs. Ancient biography made that habit possible. It turned a man from Mantua into a lens through which Rome read itself. (“The Ancient Lives of Virgil. Literary and historical studies" edited by Anton Powell and Philip Hardie; Introduction by Philip Hardie and “Biography as Commentary.” by Irene Peirano Garrison)

Virgil’s legacy endures because he never confined greatness to conquest. His Rome is not merely triumphant but mindful—an empire that pauses to grieve. In his lines, the cost of destiny and the compassion of humanity are forever intertwined.

From Mantua’s quiet fields to Augustus’s radiant capital, he gave voice to the paradox of Roman power: that civilization’s glory depends on remembrance of its sorrow. Across two millennia, readers have returned to him for the same reason Aeneas sought the Sibyl’s path—to find meaning amid loss, and order amid the ruins of history.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: