Agrippina the Younger: The First Empress of Rome, in a Male Dominant Society

Agrippina the Younger, born in 15 AD, was a prominent and controversial figure in Roman history.

Agrippina was the daughter of Germanicus, a revered Roman general, and Agrippina the Elder. As the sister of Emperor Caligula, the wife of Emperor Claudius, and the mother of Emperor Nero, Agrippina wielded immense power behind the scenes during one of the most turbulent periods of the Roman Empire.

A Prominent Female Figure in Ancient Rome

Agrippina the Younger was poised to become one of the most significant female figures in Roman history due to her prestigious family lineage within the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Her power and influence were deeply rooted in her connections to this imperial dynasty, which secured her authority across Rome and its provinces.

Her strategic marriages not only cemented her role as a mother and a wealthy noblewoman but also gave her direct access to the emperor and allowed her to exert patronage. These relationships granted Agrippina influence over powerful men in Rome, including senators and the emperor, which formed the core of her power and authority in the Roman political sphere.

Agrippina the Younger is traditionally portrayed as deeply involved in scandalous acts, including plotting against her brother Caligula (while allegedly sharing his bed), poisoning her husband Claudius with a mushroom, and attempting to control her rebellious son Nero by having an incestuous relationship with him. Ultimately, Nero orchestrated her demise through an elaborate and infamous murder plot.

However, whether these events actually occurred, is highly debatable amongst scholars.

A gravure of Agrippina the Younger's bust. Credits: Rijksmuseum, Mr.Nostalgic, CC0 1.0

While historical reputations are often shaped by perception rather than reality, the distinction between fact and fiction still matters. It may be impossible to uncover the full truth about Agrippina today, but discerning readers can hope for interpretations that strive to approach historical accuracy, rather than relying on sensational but unreliable stories. The truth about Agrippina's life and deeds remains elusive, leaving room for debate about how much of the tradition surrounding her is grounded in reality. (Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire, by Anthony Barrett)

Agrippina's Early Life

The story of Agrippina the Younger begins with her birth into the prestigious Julio-Claudian family on November 6, 15 CE. She was the first daughter of the renowned Roman general Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, granddaughter of the first emperor, Augustus.

Born in Ara Ubiorum (modern Cologne), at a military camp on the Rhine, Agrippina's early life was deeply connected to the political and military elite of the Roman Empire. Her father, Germanicus, was highly revered across the empire, seen as a symbol of virtue and military prowess, though contemporaries held differing views on him.

Agrippina's childhood was marked by the influence of her parents, especially her mother, who represented the perfect Roman woman with her numerous children and loyalty to Germanicus. Together, they formed a public image akin to modern royalty, winning the hearts of the Roman people. Agrippina the Elder, as the last surviving direct descendant of Augustus at the time, symbolized the continuation of the Julian bloodline, an important factor in Roman society where family legacy held immense value.

The All-Important Father Figure of Germanicus

Germanicus' military career, especially his campaigns in Germany, defined much of Agrippina's early years. Amid the turmoil of mutinies and wars on the German frontier, Germanicus and Agrippina faced considerable challenges. Agrippina the Elder played a significant role in stabilizing Germanicus' forces during a mutiny by using her status as the granddaughter of Augustus to rally the troops. These formative experiences occurred against the backdrop of Germanicus’ struggle to maintain loyalty among his soldiers in the harsh and dangerous environment of Germany.

In her early life, Agrippina the Younger was sent back to Rome to ensure her safety while her parents continued to lead campaigns in dangerous territories like the Teutoburg Forest, a place symbolic of a Roman military disaster under Augustus' reign. Despite these challenges, her family remained committed to the Roman cause, with Agrippina the Elder even following her husband on campaigns while continuing to bear children, including Agrippina's younger sister, Julia Drusilla, born soon after her.

Thus, Agrippina the Younger’s early years were steeped in the legacy of Roman power, imperial family dynamics, and the military struggles of the empire, setting the stage for her future role as one of the most influential women in Roman history.

The summary of Germanicus's final campaigns and death highlights his symbolic importance to Rome and the political tensions with Emperor Tiberius. Germanicus was sent to Germania, where he raised a funeral mound for Roman soldiers lost in earlier battles. Although Tacitus claims Germanicus won victories against the Germanic leader Arminius, he was recalled by Tiberius before he could fully avenge the Roman losses. Tacitus attributes this to Tiberius' jealousy, though this view may be influenced by the historian's personal disdain for the emperor.

Tiberius was wary of expanding Rome’s territory and preferred to maintain and protect existing borders, as Augustus had decreed. However, Germanicus's return to Rome was celebrated with grand honors, including being hailed as "Imperator" and awarded a triumph, a prestigious Roman military parade. Agrippina the Younger would have been around for this grand event, which helped cement her family’s prominence in Roman society.

After his return, Germanicus was sent on a diplomatic mission to Syria. While there, tensions flared between him and Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, the governor of Syria, who undermined his authority. Following a mysterious illness, Germanicus died, believing he had been poisoned, likely by Piso. This belief was fueled by Roman superstitions about witchcraft and magic, with Tacitus detailing strange objects found near Germanicus's home.

Whether Germanicus was poisoned remains unclear, as he may have contracted a disease during his travels, but the belief in his murder was widely accepted. This event shaped Agrippina the Younger’s life, as her father's legacy was maintained by her mother, and the suspicion surrounding Tiberius and Piso would influence future political dynamics. Germanicus's death at 33 left an enduring legacy in Rome, deeply impacting his daughter, Agrippina the Younger. (Agrippina, The most extraordinary woman of the Roman world, by Emma Southon)

Agrippina's Hostile Profile

The life of Agrippina the Younger offers much more than just intriguing anecdotes of poisonings, affairs, and suspicious shipwrecks. Her story is an insightful example of both the opportunities and constraints faced by a woman of imperial lineage in ancient Rome. Agrippina’s ambition was evident from early adulthood, and she made strategic moves to secure power, much like her mother and grandmother, who also sought influence.

However, Agrippina was more successful than they were, achieving a higher degree of political success. Yet, her power was constantly checked by the patriarchal structure of Roman society, highlighting the limitations placed on women, regardless of their status. Ultimately, Agrippina's rise to prominence ended in violence, reflecting both her triumphs and the dangers of navigating a male-dominated political landscape.

Agrippina the Younger captivated both ancient writers and modern scholars alike due to her significant political influence and formidable personality. She was often portrayed as wielding considerable power, especially as the wife of Emperor Claudius and mother of Emperor Nero, although the title "empress" can be misleading.

In ancient Rome, no woman held formal political power, but Agrippina’s assertive role in public affairs defied traditional gender norms, making her a controversial figure.

A relief showing Agrippina the Younger crowning Nero, from Aphrodisias’ Sebasteion. Credits: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Ancient sources, particularly Tacitus, were consistently hostile toward her, portraying her as a manipulative schemer who used deceit, seduction, and even murder to achieve her aims. Her rise to power, according to these accounts, was marked by intrigue and ambition, attributes that clashed with Roman ideals of femininity.

Despite this negative portrayal, Agrippina's influence was undeniable, and she remains a subject of fascination for historians, both for her political maneuvering and for how she navigated and challenged the gendered expectations of her time. Modern interpretations of Agrippina the Younger tend to align with ancient views of her as a power-hungry figure, driven by ambition and an unwavering dedication to securing her son Nero's rise to power.

Ronald Syme, a leading historian on Roman history, notably asserts that Agrippina embraced a more brazen form of criminality, motivated solely by her desire for power, yet always with her son's future in mind. Syme references her reputed response to astrologers who foretold that Nero would eventually kill her: "Let him kill me, provided he rules" ("occidat dum imperet"). This famous statement encapsulates Agrippina's relentless ambition, demonstrating that she was willing to accept even death for the sake of her son's supremacy.

In “Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire,” Anthony Barrett takes a more balanced and positive approach to Agrippina the Younger than most ancient or modern historians. While Barrett acknowledges that Agrippina was ambitious and politically calculating, he emphasizes her substantial political achievements. Barrett argues that Agrippina deserves credit for effective governance, particularly during the later years of Emperor Claudius's reign and the early years of Nero's rule.

He notes that Agrippina’s influence helped transform the imperial regime from one characterized by repression and frequent executions into a more cooperative partnership between the ruler and the governed. He claims that: “Clearly the Roman imperial system was unfair to a woman like Agrippina, whose talents and energies were such that she would have achieved high office, quite likely the principate itself, had she been a man.”

Barrett also casts doubt on some of the more scandalous rumors surrounding Agrippina, suggesting that while she may not have discouraged these tales, she used them strategically to bolster her image as a powerful and intimidating figure. Despite facing fierce animosity and hostile reports typical of powerful women in Roman politics, Agrippina managed to navigate these obstacles through shrewdness, determination, and alliances, effectively expanding the political roles available to women in her era. (Representing Agrippina: Constructions of Female Power in the Early Roman Empire, by Judith Ginsburg)

Tacitus’ Exemplum

In Tacitus' portrayal, Agrippina the Younger is depicted as a strategic "reader" of her own past, consciously modeling herself after notable imperial women and foreign rulers. Tacitus sees her as an exemplum, a model for others, but with a twist: Agrippina's unique position in the domus Augusta (the imperial family) makes her role nearly impossible to replicate.

Tacitus succinctly captures this by noting that Agrippina, as the daughter of a general, sister, wife, and mother to emperors, remains a "singular exemplum" to this day. Her familial ties are extraordinary: she is the daughter of Germanicus (Tiberius' nephew and adopted son), sister to Caligula, wife of Claudius, and mother to Nero.

Tacitus even notes her descent from Augustus and Livia, the founding figures of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. This genealogy places Agrippina in a class of her own, making her an exemplar, not in a way others could imitate, but as a symbol of the unique and often unattainable power dynamics within the imperial family.

Agrippina’s singular status as an exemplum in Tacitus' Annals reflects her awareness of her own symbolic role and the way she drew on diverse models of power, including those of Livia and her own mother, Agrippina the Elder. Her fertility, like that of her mother, was seen as a source of authority, and it was even used by Pallas to advocate for her marriage to Claudius.

Tacitus’ depiction of Agrippina suggests that her strategic use of family connections and public image enabled her to ascend to unprecedented heights in the imperial hierarchy, cementing her role as a unique and influential figure in Roman history:

“Since everyone urged that the emperor should marry, it was necessary to select a woman distinguished in nobility, childbearing, purity. Nor was a long search needed: Agrippina excelled in the renown of her birth. She had given proof of her fecundity, and her moral character was suitable.”

In Tacitus' account, Agrippina not only imitates the behavior and qualities of other imperial women but also leverages her own past to prematurely secure public honors that were typically reserved for her predecessors. Tacitus notes that after dismissing Lusius Geta and Rufrius Crispinus from their roles as Praetorian Prefects due to their loyalty to Messalina's children, Agrippina elevates her own status by making a ceremonial entry into the Capitoline on a carpentum (a luxurious carriage). This act symbolized a significant public honor that underscored her ambition and her desire to assert her influence in the imperial sphere:

“Agrippina also raised her own rank higher: she entered the Capitol on a carriage, which honor, granted to priests and sacred objects of old, increased veneration of the woman …”

Agrippina by Cassius Dio

Dio Cassius offers a consistently negative portrayal of Agrippina, drawing strong parallels between her and the infamous Messalina. Dio even claims that Agrippina "quickly became a second Messalina." According to him, from the outset of her marriage to Claudius, Agrippina, much like Messalina, "destroyed" numerous prominent women out of sheer jealousy.

Dio represents Agrippina as violating both customary and civil norms right from the start, noting that even before her marriage, she spoke to Claudius "more effeminate than [should] a niece." After becoming his wife, she begins accumulating wealth and property for her son Nero, "murdering many" in her quest for riches.

Dio portrays Agrippina as a departure from the ideal Roman woman, attributing to her traits of unchastity, greed, and criminality.

Agrippina the Younger's bust. Credits: HOWI, CC BY-SA 3.0

Her ferocity is further emphasized in the account of Lollia Paulina's death, when Agrippina, after ordering the killing, personally inspects Paulina's severed head, checking her teeth for unique features. This act underscores Agrippina’s barbarism and detachment from expected female behavior in Roman society.

A key aspect of Dio's depiction is his emphasis on Agrippina's hunger for money and power. He claims she would "flatter everyone who is in any way whatever well off and murders many for this very reason." Once in the imperial household, Agrippina gains control over Claudius, securing official honors like the right to ride in a carpentum during festivals and the title of Augusta.

Despite her extensive power, Dio suggests that "nothing seemed to be enough for Agrippina," as she desired Claudius' title as well. Even after Claudius’ death, Dio credits Agrippina with continued dominance, managing imperial affairs on Nero’s behalf. However, her overreach becomes untenable when she attempts to join Nero on the imperial platform, signaling a shift in her influence.

From that point, figures like Seneca and Burrus work to curtail her involvement in public affairs, and her position weakens due to the rise of other women in Nero’s life, such as Claudia Acte and Poppaea Sabina. In summary, Dio portrays Agrippina as morally corrupt and socially transgressive, indulging openly in desires for sex, money, and power. Her subversion of the traditional roles and privileges reserved for men in Roman society is a central element of Dio’s negative characterization. (Julia Augusta Agrippina and the sources: Ancient history resources for teachers, Macquarie Ancient History Association)

Agrippina's End and Recognition

Agrippina was born just after the death of her great-grandfather Augustus and witnessed the reigns of several Roman emperors: Tiberius, Gaius, Claudius, and her own son Nero. Throughout her life, she held unprecedented positions, being the daughter of a military commander, sister, niece, wife, and mother of emperors, something unparalleled in Roman history.

She dared to venture beyond traditional roles for women, exercising considerable influence and power in Roman political life. For a brief time, she ruled alongside Nero, defying societal expectations and assuming a role that was far more active and commanding than what was typically acceptable for women.

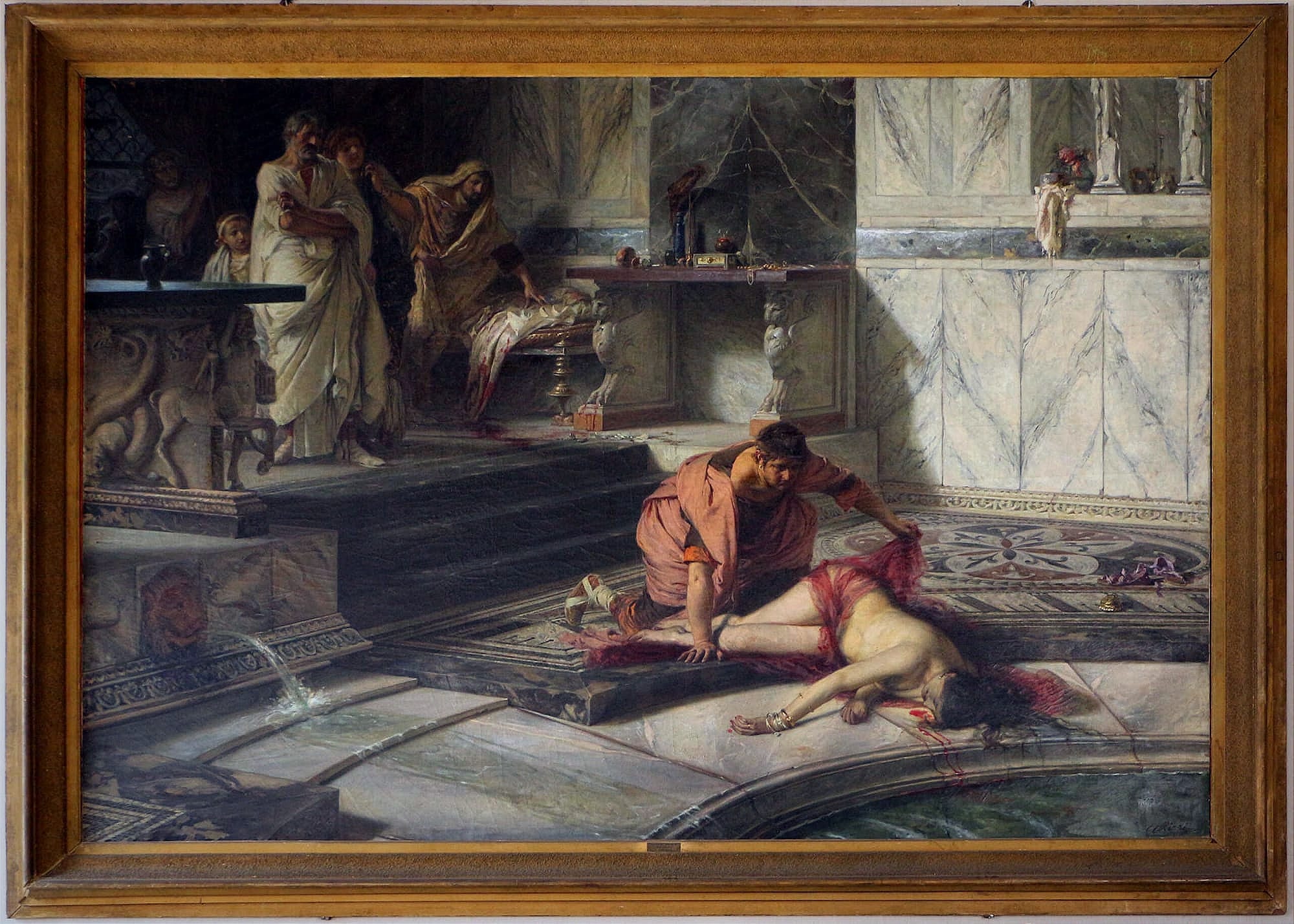

However, this brief period of power came with a harsh price. Agrippina was ultimately humiliated and either brutally killed by order of her son – Nero – or committed suicide because Nero found out that she was plotting against him, serving as both an inspiration and a cautionary tale for Roman women. It is to be noted that after her death, Tacitus reports that Nero viewed her corpse and his comment was focused on how beautiful she was. She was cremated the same night, on a dining couch.

Although many male historians have downplayed her significance, the impact of her actions was profound. It was a century before any woman attempted what Agrippina had tried. Despite the destruction of her son's legacy, forty years after her death, a statue of Agrippina was erected by Emperor Trajan in his new forum, symbolically restoring her presence in Rome and recognizing her, as Rome's first true empress.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: