This Surprising Roman Theme Spawned 300+ Paintings — Here’s Why Artists Couldn’t Quit It

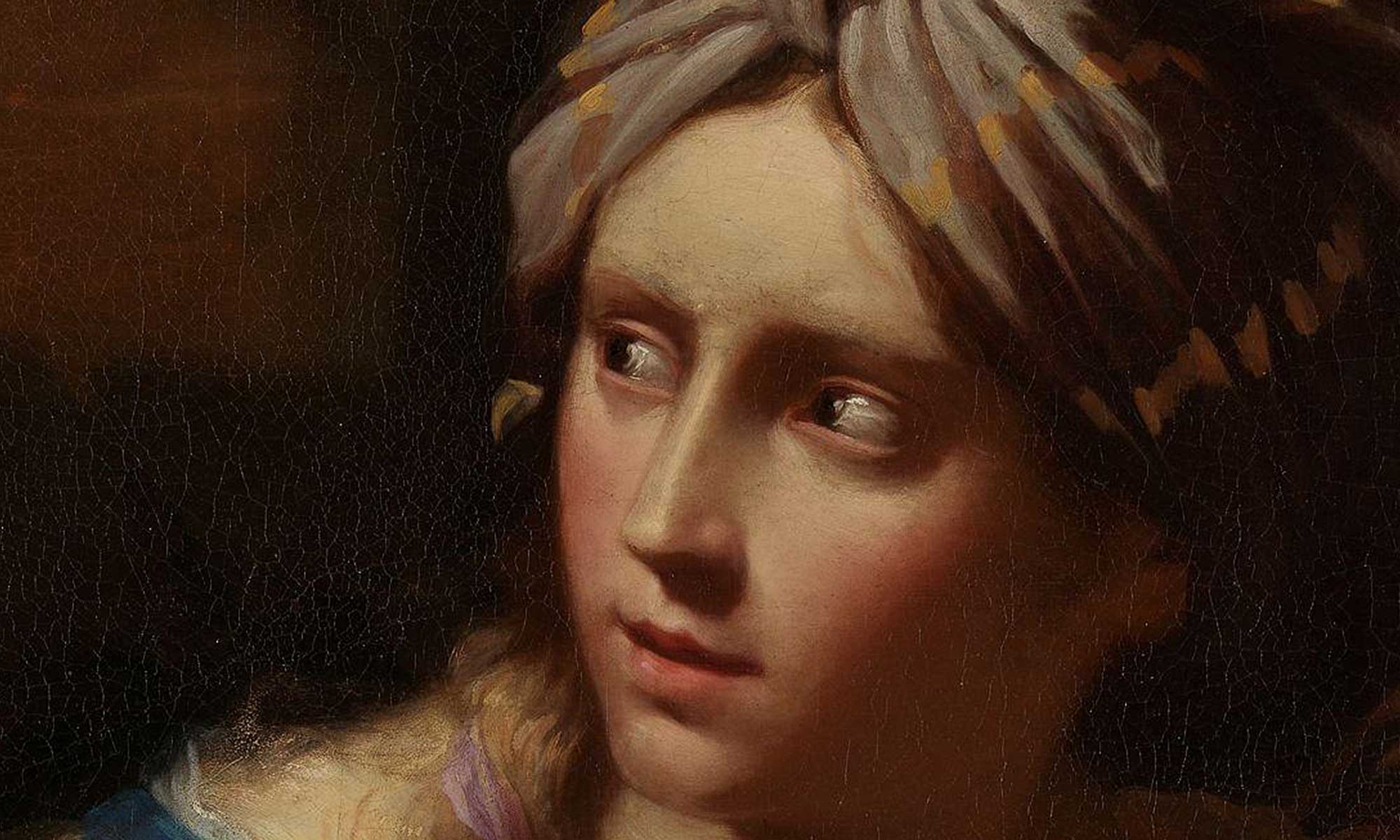

Artists treated a specific theme as lesson, controversy, and dare, painting it in registers that range from luminous piety to disquieting eroticism.

Roman Charity is the name early modern Europe gave to a short Roman tale with a very long afterlife: a daughter secretly breastfeeds a parent condemned to starve in prison. The gesture saves a life and, in the eyes of moralists, redeems a lineage.

Painters, sculptors, and printmakers made the scene one of their most repeated problems—not merely because it could be staged with potent light and intertwined bodies, but because it sat at the crossroads of politics, theology, and desire. In the following pages, we trace the story’s origins, its explosive popularity, and the many ways artists pushed the image to do moral, devotional, and even dissident work within early modern Europe.

Origins: From Roman Exemplum to Greek Precursors

The best-known source is Valerius Maximus’s Memorable Doings and Sayings (written under Tiberius), which preserves two paired anecdotes of “filial piety.” In one, a woman—later called Pero—nurses her imprisoned father Cimon; in the other, a daughter sustains her mother the same way.

Already in antiquity these acts were read as models of pietas. Later authors fold them into civic memory: Pliny the Elder recalls a column dedicated to the daughter who nursed her mother; the lexicographer Festus explains “piety” with the example of a woman secretly breastfeeding her father, and notes the goddess Pietas herself.

Around these moral exempla hovered a wider ancient vocabulary of lactation: nursing deities and kourotrophoi in the Greek world, for whom the breast signified nurture, elevation, and—often—divine favor. In short, long before the Renaissance, a daughter’s milk could be imagined as the stuff of civic virtue and sacred power.

What the Story Meant: Piety, Charity, and the Politics of Kinship

When the tale resurfaced in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, its meanings braided with Christian caritas. In theology and civic art alike, charity is both love of God (amor Dei) and love of neighbor (amor proximi).

Venetian patrons, confraternities, and civic authorities made the virtue conspicuous: Charity appears as a maternal feeder of infants, as a giver of bread, and—crucially for our story—as enacted mercy in narrative scenes. Sixteenth-century artists increasingly dramatized the virtue rather than simply personifying it, embedding Charity into Last Suppers and façade programs.

That shift matters for Roman Charity: the prison feeding could now register both as a corporal work of mercy (feeding the hungry) and as a meditation on the theological virtue itself—on love circulated among kin and, by extension, among citizens. The Counter-Reformation emphasis on good works sharpened this narrative drive; confraternal patrons wanted images that taught charity by showing it, not merely by symbol.

Why So Many Roman Charity Paintings? The Early Modern Boom

From roughly 1550 to 1700 the motif explodes. More than three hundred Roman Charity images survive in collections worldwide—on canvases and panels, in prints and medals, on maiolica, even on pharmaceutical jars. The reasons are as practical as they are intellectual:

- First, the composition is compact, theatrically lit, and studio-friendly. A shackled elder, a barred window, and a daughter’s body angled toward the mouth produce a tableau that obeys Baroque optics: close values, firm chiaroscuro, and the mental “click” of recognition. The subject could be scaled for cabinets or solemnized for chapels; it could sit inside a larger program on the virtues or anchor an altarpiece about mercy.

- Second, the scene’s semantic flexibility rewarded both painter and patron. Was this a daughter’s heroic pietas, an allegory of Charity, a political parable about rehabilitating guilty fathers, or a staged transgression that tested the viewer’s own gaze? Roman Charity could be all of these—sometimes at once. That multivalence was useful in a Europe negotiating confession, social hierarchy, and a newly public culture of relief.

- Finally, the motif arrived just as the “age of milk” gave the breast unusual discursive weight. Medical and devotional texts praised women’s milk as remedy and grace; mystics imagined nursing from the Virgin; courts argued over wet-nursing and maternal duty. Into that climate, the prison feeding of a parent could read as both orthodox mercy and a queering of kinship. Small wonder viewers could encounter the subject on a drug jar as easily as on a painted panel.

Between Piety and Desire: How Artists Tuned the Scene

Across the corpus, the same ingredients—the barred window, a shackled elder, a young woman turning her body—yield radically different effects. Some images court prayerful awe; others tip toward transgression; many sit on the knife-edge, asking the viewer to decide where mercy ends and desire begins. What follows maps the most persistent strategies painters and printmakers used to “tune” the motif.

- The stage: cell interior vs. prison grille.

Two basic theaters dominate. In the interior type, we are inside the cell: wall presses against wall; light is raked and local; the bodies fill the frame. Proximity is the point—our eyes, like the daughter’s, close the distance.

Northern engravers and cabinet-scale Italian panels favored this intimacy. In the grille type, the exchange is staged at a window or doorway; the father’s head juts through bars while the daughter leans from outside.

The barrier enforces decorum—contact occurs “properly” across a threshold—and the artist wins a bonus geometry (vertical bars, a horizontal sill) that stiffens the composition. Workshop practice often toggled between these options, selling the same narrative to different patrons: devout confraternities tended to purchase the grille variant; private collectors, the interior. - The moment: before, during, after.

Artists also choose the instant. “Before” scenes set the drama in suspended intention: the daughter loosens her bodice, a shawl is gathered, the old man’s hand trembles toward her. The viewer completes the act in imagination.

“During” scenes, rarer and riskier, lock our gaze on the latch of lips and nipple; the moral pay-off (feeding the hungry) is literal, but so is the charge of looking. “After” scenes flood relief through gesture—the daughter refastens her gown, the father’s eyes close, a cup or cloth wipes the mouth. Painters sensitive to Counter-Reformation decorum often favored the “before/after” brackets; printmakers, shielded by scale and price point, explored “during.”

- The gaze triangle.

Where do eyes land? A pious solution keeps glances downward: the father’s eyes are closed or cast to the side; the daughter’s face is turned away, lids lowered in modesty. A more theatrical solution triangulates glances: father—breast—viewer.

In some small-master prints, the daughter looks out of the picture, catching the viewer mid-look. That stare performs two tasks at once: it shames the voyeur (you are seen) and it solicits complicity (you are trusted to keep the secret). In rubric terms, the painting becomes a moral test—do you avert your eyes, or help her shield the act? - Fear of discovery.

Many variants insert a third presence whose body is only partly shown: a guard’s shadow, a key turned at a door, a foot on a stair. The fear is choreographed by props—chains, ring-bolts, iron locks—but above all by lighting.

A thin wedge of white across the threshold is enough to tell the story: mercy happens under threat. A hand to the lips (the classic sign of silence) appears in several engravings; shawls hover, neither on nor off, so that modesty is both performed and breached.

- The semantics of cloth.

Costume codes message. A sumptuously dressed Pero (silk sleeve, jeweled bodice) can signal the family’s standing and the daughter’s agency—she risks assets as well as honor. A plainly dressed Pero in workaday linen can purify the act, aligning it with the poor relief that confraternities claimed.

Painters play these codes against skin: matte fabrics thrown over porous stone make the exposed breast even whiter; velvet or satin cupped at the edge of the areola sharpens the moment of unveiling. A common device is the half-veil: the gown is opened just enough to feed and no more, reminding the viewer that what mercy reveals, mercy also hides. - Hands that tell the truth.

Even when faces are idealized, hands betray what the scene means. The daughter’s near hand steadies the father’s head, fingers learning a nurse’s craft. The far hand manages the gown; in more eroticized treatments, the thumb knowingly presses the breast from below.

The father’s left hand, when not shackled, quivers in gratitude or clutches at the bar; in bolder pictures, it grazes the daughter’s shoulder, collapsing distance further. Carvers of small plaquettes loved this choreography: thumbs, knuckles, the knotted tendons of age, and the tensile calm of youth.

- Props that preach (or tempt).

Artists salt the set with things that tilt the reading. A rosary looped at the wrist sanctifies touch; a ledger or petition on the sill turns the act into a plea for clemency; a loaf or flagon in the background folds the scene into the broader “works of mercy” (feeding, giving drink).

Conversely, a mirror or jewel placed too prominently can edge the act toward vanity. Even masonry speaks: a classical pilaster and clean ashlar say “antique exemplum,” while rough, damp walls say “contemporary prison”—a time-fold that keeps the story pointed at the viewer’s present. - Age, likeness, and discomfort.

Painters tweak ages to manage the incestuous charge. Some make the father extremely old—a bald, edentulous elder whose child-likeness erases sexual rivalry and turns feeding into pure charity. Others bring him into late middle age, with grey at the temples and a still-strong jaw; the closer he comes to erotic viability, the more the composition must work to keep the scene pious (more bars, more cloth, more downward eyes).

Family likeness—echoed noses, shared cheekbones—can either reassure (this is kin) or intensify the taboo (this is too clearly kin). Workshop variants often calibrate these dials for different buyers.

- Allegory vs. anecdote.

Some patrons asked for allegory: the daughter stands as Caritas itself; the father as Humanity or Cimon as every sinner. These pictures use attributes (flame, heart, cornucopia) and putative inscriptions to “translate” the act.

Others insist on anecdote: no attributes, only the prison and the pair. Between the two lies a vast middle, in which an overtly narrative scene borrows allegorical gravitas (architectural classicism, ideal proportions) while keeping the pulse of story. - North and South, line and mass.

Geography matters to touch. Northern workshops—print-led and enamored of the small—love the linear: hatched shadows, needlelight, and tight contours that clap the bodies together like puzzle-pieces. Italian shops, raised on large altarpieces and drawing schools, prefer mass: volumes press and release; space is sculpted by chiaroscuro rather than crosshatch.

Both rhetorics can serve piety or prurience; both can stage fear or tenderness. What they share is a faith in close looking—the viewer’s learned eye becomes the moralizing engine.

- Market logic: repetition with a difference.

Because the composition is compact and highly legible, it lent itself to series and workshop repeats. Printmakers broadcast “templates” that painters then enlarged, softened, or rehung in color.

A successful sheet could be mined for a decade; collectors learned to enjoy spotting echoes and departures. This economy of repetition explains the “hundreds” without reducing artists to copyists: each tweak—cloth gathered, gaze redirected, bar inserted—retools the ethical weather of the room. - Rubens as a case study in calibration.

Few artists demonstrate the motif’s range better than Peter Paul Rubens, who returned to Roman Charity multiple times and whose studio generated variants for different contexts. One celebrated canvas—publicized in postwar London with a detailed accounting of engravings and provenance—presents Cimon under a heavy green drape and Pero in fierce red, the pair locked in lamplight against a block of masonry.

Look at what the painting chooses: the “during” moment, but with eyes shaded; a fabric edge that frames but does not display; a third-space of shadow where a guard might be. Even in market notices contemporaries sensed how canonical the subject had become by the 1620s, and how a star workshop could adjust moral temperature for altar, palace, or cabinet.

- Pious modesty vs. charged transgression—why both survive.

It would be easy to divide the corpus into “edifying” and “erotic,” but the endurance of the motif lies in works that resist that binary. Painters discovered that modesty itself could be thrilling—the held breath before a knock at the door; the mercy that must be hidden to remain pure.

Conversely, overtly charged pictures smuggle in mercy by making the old man pitiable enough that the breast seems, paradoxically, less sexual because it is so psychologically necessary. That unstable mix proved irresistible to patrons who wanted images that taught and tested, moved and unsettled. Roman Charity thrived where it refused to settle, and the best artists learned to keep it unsettled on purpose. - What viewers learned to see.

The motif taught an early modern public to read gesture and light as moral arguments. A turned wrist could redeem a bare breast; a strip of shadow across an eye could convert erotic proximity into fearful obedience; a single bar, drawn a finger’s width closer to the foreground, could convert scandal into sacrament.

That literacy—practiced in churches, guildhalls, and corridors—helped European viewers make sense of a culture where images were asked to do a great deal: to instruct, to plead, to comfort, to warn, to entertain, and to sell.

In short, “Roman Charity” is not one picture but a grammar of pictures—choices about place and moment, gaze and cloth, threat and relief—through which early modern artists turned a brief Roman anecdote into one of Europe’s most elastic moral theaters.

The Caravaggesque Shock — and What Followed

The turning point is Caravaggio. In 1606 he threaded Roman Charity through his Neapolitan altarpiece, The Seven Works of Mercy (Sette opere di misericordia). At a street-corner theater of aid—feeding, clothing, sheltering, burying—the old man’s head juts through prison bars to nurse from a woman who bends toward him.

Early descriptions notice the vignette at once. The move mattered: Caravaggio dragged the anecdote out of the “private” cell and into the traffic of urban mercy, collapsing personal sustenance into public charity. His followers responded en masse.

Caravaggisti across Italy and the North—Manfredi, Honthorst, van Baburen, Vouet, Lo Spadarino, and others—painted Roman Charity alongside hallmark Petrine subjects; meanwhile Rubens and Guido Reni, who briefly flirted with Caravaggism, produced their own versions starting around 1612. The chain reaction shows how the motif served as a live wire for experiments in tenebrist light, close-up bodies, and morally fraught staging.

Caravaggio’s pairing of the nursing scene with Petrine themes prompted deeper readings. Viewers noticed a family resemblance between the suckling father and Caravaggio’s Saint Peter—a visual echo thick with irony in a post-Tridentine culture wrestling with papal authority, repentance, and grace.

Patrons doubled down on the dialogue, commissioning and hanging altarpieces so that Peter’s angel-led liberation faced the nursing of Cimon, as at the Pio Monte where Battistello Caracciolo’s Liberation of Saint Peter enters into a programmed conversation with Caravaggio’s altarpiece.

The suggestion is sharp: in both canvases, release comes not primarily from contrition but through intervention—angelic in one case, a daughter’s breast in the other. Roman Charity thus worked as a figure of dissent within Counter-Reformation decorum, softening the terms of guilt and rehabilitation by staging salvation as nourishment.

Afterlives and Objections: Medicine, Morals, and the End of Roman Charity

Roman Charity’s reach rests on more than painterly fashion. It sits at the hinge of discourses that early modern people cared about: who nourishes whom (kinship and law), how mercy should be staged (devotion and politics), what a breast is “for” (theology and medicine), and where eroticism begins (ethics and censorship).

That is why the image could travel—without losing its charge—from court and confraternity to private cabinet.

The medical backdrop mattered. Ancient authors such as Dioscorides praised human milk for lung disease, ulcers, eye problems, and gout—especially when taken “directly from the breast.”

Renaissance writers updated the file. Marsilio Ficino theorized rejuvenation through young women’s blood and milk; physicians like Geronimo Acoromboni prescribed extended milk cures to notable patients (Cardinal Pietro Bembo among them). Reports of adult breast-feeding practices—some devotional, some therapeutic—crawled across letters, sermons, and plays.

The most notorious anecdote has Pope Innocent VIII ingesting boys’ blood and then turning to a wet-nurse in his last days; even if retold in hostile tones, the episode shows how intelligible “adult milk” was in elite culture. In that world, the prison feeding of a parent is an extreme of a broader possibility set, not a lone monstrosity.

At the same time, the image always provoked unease. Early modern languages preserve a difference between infant “milking” and adult “breasting,” a sign that communities policed meanings at the very word level.

Satirists took aim; preachers warned; and artists learned to place modesty props and narrative buffers—bars, shawls, turned heads—to limit voyeurism without erasing contact. And yet the corpus kept growing. The sheer scale—more than three hundred extant examples across media and regions—reminds us that viewers found the picture “good to think with.”

They could use it to consider the economy of salvation (Is mercy a gift that rehabilitates the undeserving?), to test political allegory (Is the father a figure of patriarchal power that must be sustained yet reformed?), and to rehearse the theater of compassion.

By the later eighteenth century, a new domestic regime and a new medical chemistry altered the image’s reception. As maternal exclusivity hardened—wet-nursing condemned, foundling hospitals contested, formulae and bovine substitutes debated—the idea of milk circulating beyond the mother-infant dyad became suspect.

The motif’s intelligibility waned. Rousseau cast exclusive maternal nursing as moral restoration; bourgeois privacy narrowed symbolic bandwidth; Roman Charity retreated to footnotes, storerooms, and specialized taste. (Roman Charity: Queer Lactations in Early Modern Visual Culture, by Jutta Gisela Sperling)

In truth, its afterlife continues in quotations, refusals, and revisions—from anti-Roman Charity cartoons to contemporary queer re-stagings that press on the image’s old fissures. If the tale still startles, it is because its drama is unresolved: a daughter’s body rescues her father’s name; an old order survives by a new gift; “charity” disturbs the very kinship it claims to restore.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: