The Roman Poet of Sharp Words: Martial and his Rome

Martial was a Roman poet, the man behind the epigrams, who is remembered for his razor-sharp commentary

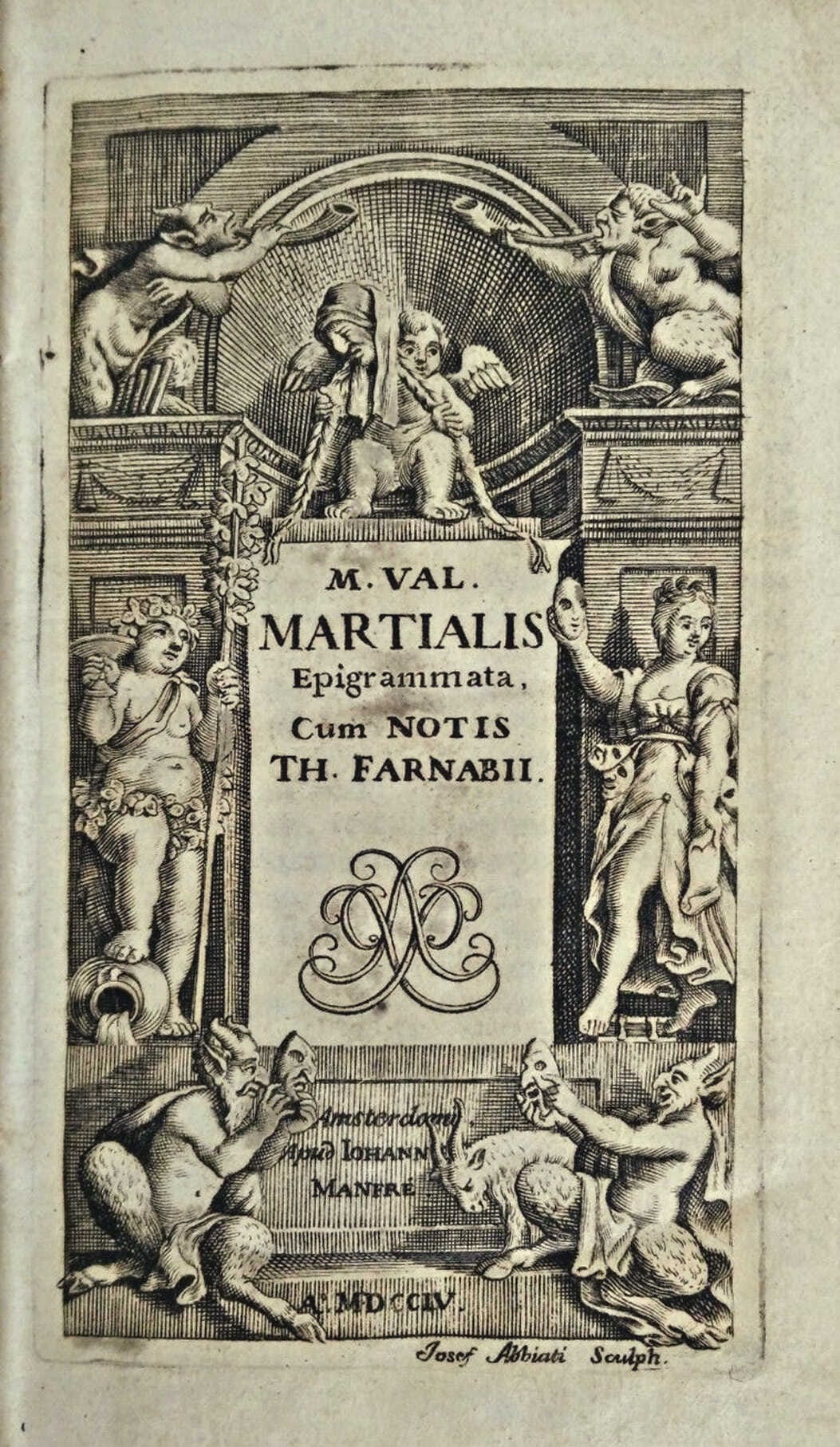

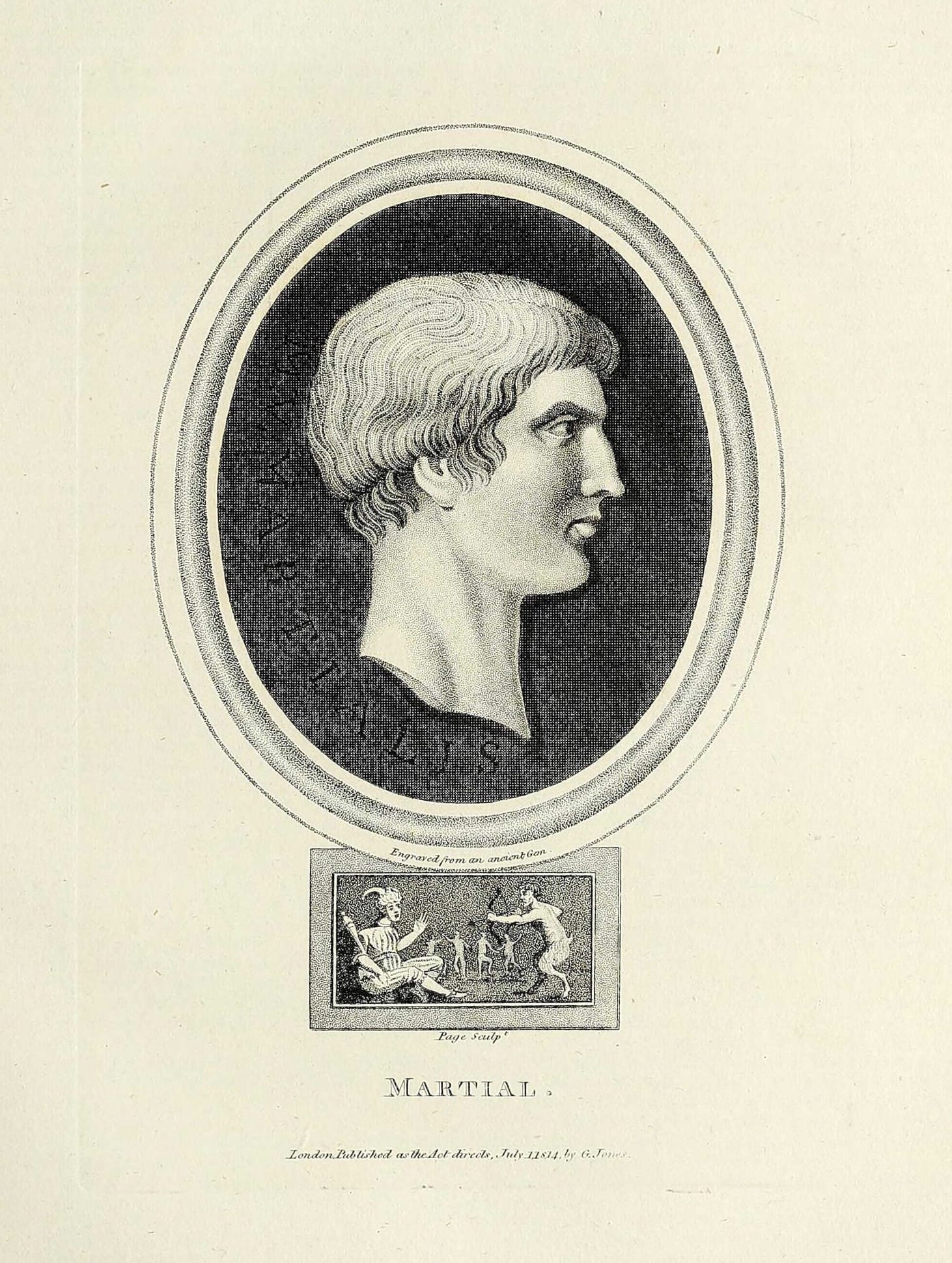

Marcus Valerius Martialis, better known as Martial, remains one of the most interesting voices of ancient Rome. Living in the busy heart of the empire during the 1st century CE, Martial is celebrated for his Epigrams—sharp, witty, and often biting verses that captured the essence of Roman society.

Through his keen observations, Martial offers us a window into the lives of both the elite and the ordinary, revealing their virtues, vices, and absurdities with unparalleled humor and honesty.

While his works are often remembered for their humor and satirical tone, Martial’s poetry also serves as a touching reflection on themes of friendship, patronage, and the pursuit of artistic recognition in a complex and hierarchical world.

Epigrams as a Lens on Roman Consumer Culture

Martial’s epigrams not only captivate with their sharp wit and vivid depictions of Roman life but also offer remarkable insight into the consumer culture of Imperial Rome. Through his over 1,500 epigrams, he explores key phenomena such as buying, gift-giving, the extension of credit, and deceptive advertising—central aspects of the Roman experience under the Flavian dynasty.

His works depict a world where economic exchanges and social relations intertwine with venal calculations, challenging idealized notions of communal bonds and generosity.

Roman poet Martial bronze bust. Credits: VICMAEL Victor Manuel, Upscaling by Roman Empire Times

Scholars have interpreted Martial’s materialistic focus as reflective of various dimensions of Roman life: the precarious mindset of free but impoverished individuals, the festive atmosphere of Saturnalia, or even as a strategic rhetorical pose to attract wealthy patrons. Additionally, his poetry serves as a poetic record of urban life, navigating the wealth and contradictions of a city that embodied the reach and complexity of a global empire.

Martial’s epigrams also delve into the mechanics of economic exchange, beginning with the nature of coins as both uniform numerical counters and unique objects, a duality that mirrors the aesthetic tension throughout his work. He captures the dynamics of gift lotteries—cheap tickets exchanged for gifts—highlighting the tension between accumulation and release that pervades his poetry.

The epigrams further grapple with the temporal disjunction inherent in credit and loans, reflecting Martial’s personal frustration with the lack of time to write, even as he dreams of communal ownership and personal autonomy.

Another recurring motif is “goop”—substances smeared onto people or objects—which Martial uses to evoke fantasies of social mobility, aspirations of ownership, and even memories of the deceased. This "goop," a material metaphor for false appearances, mirrors verbal practices like deceptive advertising, shedding light on the fantasies and contradictions that sustain consumerism in Martial's Rome.

Martial's Unique Writing Style and Use of Objects

Reading Martial reveals a striking contrast with much of other Latin literature due to his focus on less lofty themes: the buying and selling of sex, books, and various consumer goods; the relentless pursuit of loans and gifts; the anxiety of navigating a society marked by unequal and often imperfectly reciprocated exchanges; criticizing those both above and below in the Roman social hierarchy; and unflinchingly exposing the world of self-serving calculations lurking beneath dominant cultural ideologies.

A new model for interpreting Martial’s realism and materialism suggests that gift-giving, buying, and lending function in his work not only as recurring themes but also as poetic forms. Examining the drives, competing logics, and sensations associated with these activities as presented in the Epigrammaton Libelli reveals a language that reflects the structure and essence of the epigrams.

This approach involves close reading at the individual level while maintaining attention to intratextual and intertextual connections—verbal, formal, and thematic links within Martial's corpus and between his work and that of other authors. It also offers a fresh perspective on a central question in Martial scholarship: was Martial’s life truly as precarious as his writings suggest, or why did he construct such a vivid persona preoccupied with financial struggles?

Finally, this perspective situates Martial within a broader theoretical framework used to identify socio-economic and socio-political commentary in poetic forms, especially in Greek and Latin texts. This method embraces Martial’s tendency to associate disparate images and institutions, cutting across various facets of life and navigating the complex Imperial Roman social scene with spontaneity, as seen in Epigram 12.28:

“Hermogenes is so great a thief of napkins, Ponticus, as Massa hardly was, I suppose, a thief of coins; watch his right hand and hold his left one all you like, he’ll find a way to pull away your napkin: Thus does the inhalation of a stag suck out a cold snake, thus does Iris snatch water about to fall from on high.

When recently a discharge was sought for the injured Myrinus, Hermogenes stole away with four napkins.

When the praetor wanted to drop his chalky napkin, Hermogenes pilfered the praetor’s napkin!”

The poem expands upon examples of Hermogenes’ thefts, describing him stealing tablecloths, couch coverlets, and, if given the opportunity, theater awnings, ship sails, linen garments from Isis worshippers, and even dinner napkins. These vivid, sensory-rich images illustrate Martial’s epigrammatic style, where striking impressions—such as a snake drawn out by a stag's nostrils—emerge briefly before yielding to new imagery.

This imaginative approach creates a network of "napkin-like" objects and scenarios tied to theft. Martial employs wordplay, such as the mention of Baebius Massa, whose name resonates with mappa (napkin), emphasizing phonetic connections. While the poem nods to Catullus 12’s take on napkin theft, Martial focuses more on the practical properties of napkins than on metapoetic engagement.

Hermogenes’ obsession with napkins and similar objects drives the poem, reducing actual napkins to just one of many items in his pathological fixation. The shared visual symbolism of snakes, rainbows, sails, and flags underscores Martial’s ability to blend imagery with economic themes like coinage, which he introduces at the poem's start.

This interplay highlights Martial’s method of shifting between images while drawing connections to economic systems, possibly reflecting his social position.

Martial's Personal Life

Despite his frequent use of other voices, Martial’s corpus provides biographical details. Born around 40 CE in Bilbilis, Hispania Tarraconensis, Martial moved to Rome in 64, likely with support from elite Spanish-connected families like the Annaei. His literary career began well before Liber Spectaculorum, followed by Xenia and Apophoreta, and twelve subsequent collections of around one hundred epigrams each, showcasing his mastery of the form.

Martial's career spanned the reigns of at least Domitian, Nerva, and Trajan, and possibly Titus, Vespasian, and even Nero. Domitian and his freedmen, particularly Parthenius, feature prominently in Martial's works. However, many scholars suggest that Martial struggled to adapt his writing to the shifting ideological climate after Domitian's fall.

Despite offering praise for Nerva in Book 11, which also criticizes the tyranny of Domitian, Martial eventually left Rome around 98 CE, returning to Spain, where he died around 104 CE. His death was noted by the younger Pliny, who recorded that he had provided Martial with funds for his sea journey from Pyrgi.

Accepted biographical details about Martial include his modest upper apartment on the Quirinal Hill, a year spent in Forum Cornelii (modern Imola), and his connections to the poet Lucan and Lucan’s widow, Argentaria Polla. Martial also received a villa at Nomentum and another in Bilbilis, the latter gifted by a Spanish woman named Marcella upon his return.

He was honored with an honorary tribunate from one of the Flavian emperors and received the ius trium liberorum (a privilege for fathers of three children) from both Titus and Domitian. While Martial had a background in law, he showed little interest in practicing as a lawyer.

There is some speculation about Martial's personal life. The names Fronto and Flaccilla may have been his parents, but the suggestion that Martial had a wife, still remains a matter of debate. (Martial and the Poetics of Popular Consumption, by Elliott Gene Piros)

The Knightly Poet and his Life in Imperial Rome

Martial, like earlier poets Tibullus and Ovid, was a Roman knight, a status that influenced his approach to literary patronage and self-representation. While his epigrams often depict a struggling poet seeking support, Martial deliberately included autobiographical details to counter such an impression.

He desired patronage but not as a means of escaping poverty, emphasizing his social position through the honors he received, such as the ius trium liberorum (granted by Titus and Domitian), a tribunate, and his equestrian rank. Martial took pride in his ius trium liberorum, granted despite being childless and possibly unmarried at the time.

This honor elevated his social status, granting exemptions from certain civic duties and priority in magistracies. His tribunate and knighthood also underscored his standing, suggesting he had the requisite wealth for an equestrian—a minimum of 400,000 sesterces. Though Martial’s early years in Rome remain unclear, he was well-connected with influential figures like Lucan’s widow, Polla Argentaria, (as already mentioned above) and shared patrons with the poet Statius.

Contrary to his portrayal as a destitute poet, Martial owned property, including a domus in Rome and a rural estate near Nomentum, the latter serving as a retreat rather than a source of income. He also maintained urban gardens and made improvements to his properties, further evidencing his financial stability.

While he sought patronage, his status as a knight and landowner suggests he lived comfortably, using his poetry to assert his position and influence rather than merely to survive.

Martial’s literary career began during the Flavian period, marking a shift to poetry possibly influenced by his social connections and circumstances rather than economic necessity. His works reflect a careful self-presentation, aligning with his role as a poet of renown and securing his place in the social and literary circles of Imperial Rome. (Martial: Knight, Publisher, and Poet, by Walter Allen, Jr., Martha J. Beveridge, William J. Downes, Hugh M. Fincher III, Barbara Kirk Gold, E. Christian Kopff, Lawrence J. Simms and Lois H. WalshSource: The Classical Journal)

Martial’s Rome: Satire, Professions, and the Social Hierarchy

Martial provides a unique window into the social dynamics and professional landscape of Imperial Rome. Unlike many Roman authors, he did not strictly adhere to the aristocratic disdain for the lower classes but instead scrutinized life across all social levels with a sharp and often unsympathetic eye.

His works are rich in commentary on more than 60 occupations, ranging from magistrates and lawyers to barbers and mule drivers. Martial’s poetry reveals his disdain for manual labour, a sentiment shared by the Roman elite, who often viewed honest work as degrading. This societal attitude stemmed from a reliance on slaves and freedmen for labour.

However, Martial's satire targeted not only the labouring classes but also wealthier professionals such as doctors, teachers, and lawyers, whose professions he mocked with biting wit. His epigrams illustrate the tension between Roman dignity and the realities of economic survival, often pointing out the irony of impoverished aristocrats clinging to their status rather than engaging in work. His world was a bustling city with a highly specialized division of labour, yet many professions—such as teaching and medicine—were socially stigmatized for freeborn Romans.

Despite these prejudices, Martial’s works reflect the complexity of Roman social life and the economic disparities that defined it. By lampooning individuals from all walks of life, he offers a candid and often humorous critique of the professions and values of his time. As Martial himself remarked, his pages “smack of humanity,” reflecting the full spectrum of Roman life, both noble and ignoble.

Martial's Scathing View of Roman Physicians

Martial’s epigrams frequently target physicians, whom he portrays as both incompetent and unscrupulous. His contempt for the medical profession is echoed in anecdotes that ridicule specific practitioners. For instance, he mocks Herodes, caught with a stolen ladle, and Diaulus, who transitions from surgeon to undertaker, a change Martial claims aligns well with his previous method of “putting patients to bed.” Similarly, an eye specialist turned gladiator is humorously deemed no more destructive in his new role than in his old one.

Martial also lampoons the chaos of medical education through Symmachus, a doctor who brings a hundred students to a patient’s bedside, leaving Martial to lament, “I had no fever, Symmachus; now I have.” Other physicians, such as Andragoras, are caricatured as so ominous that merely dreaming of one, like Dr. Hermocrates, could lead to death.

Notably, his epigrams do not redeem a single physician from his harsh critique, painting the entire profession as both inept and disreputable. Curiously, despite the known profitability of medicine in Roman society, none of the doctors Martial mentions are portrayed as wealthy. His relentless ridicule suggests a deep distrust and low regard for the profession, shared by many of his contemporaries.

Critique of Roman Teachers: Contempt, Humor, and a Singular Tribute

His work often also ridicules Roman teachers, portraying them with a mix of disdain and humor. Reflecting the broader societal view of the time, Martial describes the teaching profession, particularly elementary educators (ludi magister and grammaticus), as poorly respected and underpaid.

His scorn is especially directed at elementary teachers, whom he derides for their early morning noise and harsh discipline, likening their loud voices and resounding blows to the clamor of blacksmiths or amphitheaters. Martial quips that the ferule, a disciplinary tool, was more cherished by the teachers than by their students, and he shudders at the thought of his poetry being butchered by a pompous pedagogue.

Martial reserves pitying disdain for teachers of rhetoric (rhetors), mocking them for their absent-mindedness and pretentiousness. He recounts anecdotes, such as Apollodotus, a rhetorician who memorized names from notes but was still praised for greeting someone without checking them. Similarly, Sabineius, another rhetorician, is humorously described as chilling the baths of Nero with his presence.

Despite his biting critique, Martial offers a surprising and sincere tribute to Quintilian, the renowned rhetorician, calling him “illustrious guide of errant youth” and “glory of the Roman toga.” This acknowledgment demonstrates Martial’s ability to see beyond his prejudices and judge individuals on their merit rather than as representatives of their professions.

Wit, Critique, and Friendships with the Legal Profession

He also frequently engages with the legal profession, blending humor, critique, and begrudging respect. Law was a highly esteemed career path in Rome, often pursued by knights, senators, and ambitious plebeians. However, Martial himself dismissed the profession, finding it too noisy, stressful, and contrary to his temperament. His disdain is encapsulated in his wish for "days without lawsuits."

Martial’s critique of lawyers often targets their pomposity and verbosity. He mocks Postumus, who, in a minor case involving three goats, grandiosely invokes Rome's glorious history, prompting Martial’s sarcastic reminder to focus on the goats. Another lawyer, Caecilianus, is ridiculed for his endless oratory, with Martial humorously suggesting he drink from a water clock to quench his thirst mid-speech.

Martial also critiques the profession’s susceptibility to bias, as exemplified by Ponticus, who refuses cases that might offend wealthy patrons. While Martial acknowledges the financial rewards of law, often contrasting them with the modest earnings of poets, he also highlights the profession’s challenges. He notes the common jest that legal fees often consumed the contested funds, leaving plaintiffs worse off.

Despite his criticisms, Martial maintained friendships with several prominent lawyers, including the famed Quintilian and Pliny the Younger, whose intellect and eloquence he admired. His relationship with the celebrated advocate Regulus, however, is more ambiguous, as Martial’s praise contrasts with Pliny’s disdain for the same figure. Ultimately, Martial’s views on lawyers reflect his dual attitudes: a rejection of the profession for himself and an appreciation of its honorable place in Roman society.

His epigrams capture the quirks and contradictions of legal practice while celebrating the individuals who excelled within it.

A possible representation of Pliny the Younger, performing an oratory as a lawyer. Illustration: Midjourney

A Poet’s Pride and Plight

Martial, despite his critical outlook on various professions, held poetry in the highest regard, treating it as both a vocation and a sacred trust. He esteemed the literary art, maintaining a professional attitude toward authorship and honoring both classical and contemporary poets. Catullus was his favorite among the ancients, but Martial resented those who dismissed contemporary poetry, as shown in his pointed quip:

"You honour, Vacerra, the ancients alone,

and never praise poets unless dead and gone.

Your pardon, if unceremonious I seem,

but it's not worth while dying to gain your esteem."

Martial reserved his sharpest wit for mediocre poets, especially plagiarizers, whom he scorned for tarnishing the dignity of poetry. To critics, he responded with incisive humor:

"You damn every poem I write,

yet publish not one of your own.

Now kindly let yours see the light,

or else leave my damned ones alone."

As a poet, Martial was deeply aware of the challenges of his craft, often lamenting the lack of financial support and leisure necessary for creative excellence. He envied poets like Vergil, who thrived under wealthy patrons like Maecenas, and frequently criticized society’s preference for worldly success over artistic achievement. Yet, Martial cherished the enduring immortality poetry could provide, a reward far greater than material wealth:

"I am poor, I admit, and I always have been, Callistratus, and yet I am no unknown, unheralded knight; no, I am read by many in all parts of the world, and people say of me, 'Look! There he is!' and what death has given to only a few, life has given to me.

But your roof rests on a hundred columns, and your money chest keeps close guard on a freedman's wealth; broad acres of Syene on the Nile acknowledge you as master, and Gallic Parma clips for you numberless flocks.

Such we are, you and I; but what I am you cannot be; what you are any one at all can be."

In the end, Martial's love for poetry transcended its hardships. He believed it was the noblest calling, offering rewards beyond material riches and a legacy that outlasts the fleeting splendor of wealth. (Martial Looks at His World, by John W. Spaeth, Jr., The Classical Journal)

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: