The Plague of Cyprian: Disease, Faith, and Crisis in the Roman Empire

The Plague of Cyprian ravaged the Roman Empire in the 3rd century, killing thousands daily. Beyond its mystery symptoms, it reshaped society, challenged imperial power, and fueled Christianity’s rise.

In the middle of the third century CE, as Rome staggered under military invasions, political chaos, and economic decline, another invisible enemy struck with devastating force. The Plague of Cyprian, named after the bishop of Carthage who described its horrors, swept across the empire from 249 to 262 CE.

It killed thousands each day in Rome alone, emptied towns, and terrified communities already weary from crisis. Yet its legacy went far beyond the mystery of its symptoms: it reshaped social bonds, exposed the fragility of imperial power, and offered new strength to a rising faith that would transform the empire — Christianity.

A Plague in the Heart of Empire

Disease was never far from Roman life. Endemic ailments such as malaria plagued populations constantly, and outbreaks appear in Roman histories and poetry. Among the great epidemics remembered in antiquity are three: the Antonine Plague of the late 2nd century CE, the Cyprian Plague of the mid-3rd century, and the Justinianic Plague beginning in the 6th century.

Modern scholarship has lavished attention on the Antonine and Justinianic outbreaks, in part because they are thought to have reshaped population and power in visible ways. The Cyprian Plague, however, unfolded at the very heart of Rome’s political crisis in the 3rd century, and though contemporary testimony about it is plentiful, it has long been neglected.

New evidence makes its study timely. Mass graves in Thebes and in Rome, combined with numismatic motifs and Christian writings, confirm the presence of a devastating epidemic in the years around 250–270 CE. The one detailed list of symptoms comes from the bishop Cyprian of Carthage, though it is far briefer than Galen’s medical notes on the Antonine Plague.

This absence of clinical detail helps explain why competing diagnoses remain, from smallpox to measles to bubonic plague. A closer look at the symptom pattern, however, suggests the disease resembled a viral hemorrhagic fever such as Ebola.

The Plague and the Crisis of the Third Century

The outbreak coincided with the Crisis of the Third Century, an age of upheaval following the assassination of Severus Alexander in 235 CE. His murder by mutinous generals on the German frontier ended dynastic succession and left the empire at the mercy of “barracks emperors”—soldiers elevated for battlefield success and cut down when fortune turned. Alongside this political fragility came economic decline, triggered by the Severan debasement of currency and rising military costs, and unceasing frontier wars.

This turbulence makes the plague’s history difficult to trace. Records are fewer than in the time of Augustus or Hadrian, and emperors rose and fell too quickly for clear narratives to form. Still, certain points emerge. The epidemic spanned at least eight emperors, beginning under Decius (249–251 CE) and continuing until Claudius II (268–270 CE), who himself succumbed during a renewed outbreak at Sirmium.

Egypt appears as the likely origin: in 249 CE, a bishop in Alexandria wrote of a disease present in every household. Riots in that same year may have carried contagion into the ranks of soldiers and spread it along imperial networks.

In Rome the plague made itself known in 251 CE, when Hostilian, son of Decius and adopted heir of Trebonianus Gallus, died of the disease. Gallus, unpopular for his passivity, remained in the city and lashed out ineffectively at Christians. His inaction prompted the general Aemilian to march on Rome, leading to Gallus’s assassination and Valerian’s elevation.

Valerian and his son Gallienus divided imperial duties, but the plague afflicted their armies. Valerian was eventually captured in the East, leaving Gallienus sole emperor during the years when the epidemic seems to have struck hardest. Though the legions were not destroyed, outbreaks in their camps weakened them repeatedly, compounding the empire’s fragility.

Literary Testimonies

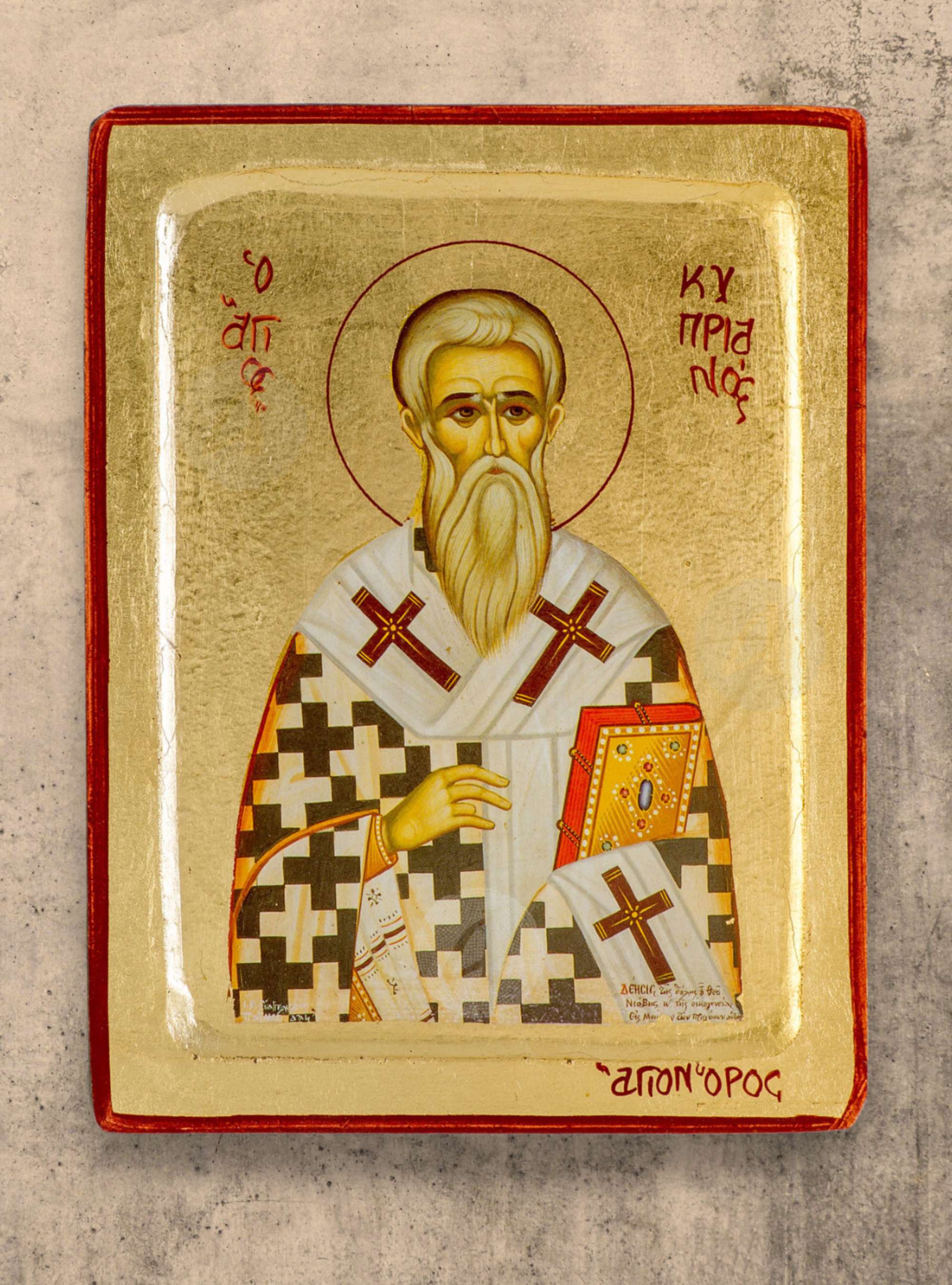

Cyprian of Carthage

The plague takes its name from Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, whose writings provide the only extant symptom list. In one letter, he responds to accusations that Christians had caused the disaster, countering that the epidemic exposed the corruption of individuals and that Christians, unlike their accusers, would find salvation beyond death. In his treatise Ad Demetrianum, he argued against pagan charges, insisting that the plague was not due to Christian impiety.

“…You accuse of the crime of plague and disease, although by plague itself and disease the crimes of individuals are either detected or increased, while mercy is not shown the weak and avarice and rapine await open-mouthed for the dead.”

St. Cyprian, Ad Demetrianum

His most important testimony is the sermon De Mortalitate, delivered around 252 CE, when compulsory sacrifices were being enforced throughout the empire. In it, Cyprian exhorts Christians not to fear the epidemic but to endure it as a trial of faith and a passage to eternal life. Here he gives his vivid description of the disease: severe diarrhea, burning fevers that ulcerated the throat, constant vomiting, inflamed and bloody eyes, gangrene consuming limbs, and long-term consequences including deafness and blindness.

“That now, the bowels, loosened into a stream, dissipate the strength of the body; that the fire taken up from the marrow boils up into wounds of the throat; that the intestines are shaken by constant vomiting; that the eyes burn with the force of blood; that the feet or other members of the body are amputated by the rottenness of the diseased infection; that either the gait is crippled through loss and weakness of the body, or hearing is obstructed, or sight is blinded—this serves as a proof of faith.”

St. Cyprian, De Mortalitate

Dionysius of Alexandria

Letters from Alexandria, preserved through later transmission, add more. In one, Dionysius remarks that after the epidemic, the number of people aged fourteen to eighty was less than the pre-plague tally of those aged forty to seventy, implying shocking mortality.

Another describes multiple deaths within each household and contrasts Christians—who cared for the sick and buried the dead—with pagans, who abandoned the afflicted but still fell ill. The rhetoric may exaggerate the moral contrast, but it underscores the epidemic’s contagiousness and places its beginning firmly in Egypt, earlier than the Carthaginian accounts.

"So that the number of people from fourteen to eighty years old no longer equals the number from forty to seventy before the disaster." Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica (Book 7, chapters 22–23)

"It would have been enough if only the first-born of each had died; but now death has carried off multitudes in every house." Eusebius, HE 7.22.10–11

He then contrasts behavior:

Christians —

"most of our brethren, in their exceeding love and affection, spared not themselves and clung to one another, visiting the sick without thought of danger, ministering to them continually, and treating them for their healing in Christ."

Pagans —

"the heathen behaved in the very opposite way. At the first onset of the disease they thrust away those who began to be sick, and kept aloof even from their dearest; they cast them half-dead into the roads, and treated unburied corpses as vile refuse, hoping thereby to avoid the spread and contagion of the fatal disease; but do what they might, they found it difficult to escape."

Other Contemporary Witnesses

Other near-contemporary voices also refer to the plague. A Christian deacon, Pontius, who later wrote Cyprian’s biography, described a devastating epidemic that killed many daily and transcended borders.

Another text, De laude martyrii, emphasized the novelty and mortality of the disease, portraying it as an unknown scourge that wasted entire cities and urged Christians to seek glory in martyrdom rather than fear infection. These accounts reinforce the scale and horror, even if tinged with theological interpretation.

Writers of the fourth to twelfth centuries continued to record memory of the third-century pestilence, often citing earlier, now-lost sources. Some late reports describe the plague as lasting fifteen years or being spread by contact with clothing or even sight. Others link it to the advance of the Goths or to poisoned air. Though colored by later biases, these accounts confirm that the epidemic left a long impression.

Archaeological Evidence

Coinage

Material culture offers further support. In these decades, coinage frequently emphasized divine powers. Apollo Salutaris, god of healing, appeared on coins of emperors such as Gallus, Volusian, Aemilian, and Valerian.

Depicted nude with a laurel branch and lyre, Apollo was linked to the emperor as a source of health and protection. Gallienus later paired Apollo with the legend Salus Publica, highlighting hopes of safeguarding the people. Such imagery signals an official recognition of plague and an appeal to divine healing.

Mass Graves

Excavations add physical testimony. At the catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus in Rome, more than 1,300 bodies were deposited hastily in layers, with alternating orientations to conserve space. In Thebes, Egypt, a mass grave was discovered where victims were covered with lime, perhaps to suppress miasma or to preserve remains, and lime kilns on site may have been fueled by burning coffins and bodies.

Other possible plague burials have been noted at San Callisto in Rome and, more recently, at Parion in Asia Minor, though dating is less secure. Such large, hurried deposits show unusual mortality crises consistent with epidemic disease.

Diagnosing the Plague

A Method from the Antonine Precedent

Determining the identity of an ancient epidemic is fraught with difficulty. Many signs—fever, chills, vomiting—are nonspecific. With the Cyprian Plague, the problem is sharper still: no medical author like Galen observed it, and only a handful of lines describe symptoms.

To approach it, a method known as differential diagnosis is used. Each symptom is weighed against diseases known to produce them; those that do not fit are eliminated until the closest match remains. This technique has been applied successfully to the Antonine Plague of the late 2nd century.

That earlier epidemic benefits from Galen’s scattered but firsthand accounts. He noted rashes, gastrointestinal bleeding, cough, and high fever, with death clustering around the ninth to twelfth day. Some patients survived, but those with blackened exanthem or blood-darkened stool nearly always perished.

Such patterns ruled out bubonic plague and typhoid, leaving hemorrhagic smallpox as the most convincing identification. This precedent shows both the value and the limits of ancient reporting: absence of a symptom cannot always be taken as proof of its absence, but repeated positive signs can guide diagnosis.

Evaluating the Diagnoses

Smallpox and Measles

Both smallpox and measles have been frequently proposed. Measles is easily discounted: it causes a flat rash across the body, not mentioned by Cyprian, and usually strikes children most severely, whereas sources imply widespread adult mortality. It also grants lifelong immunity, making recurring outbreaks in the same cities unlikely.

Smallpox fits more closely. Its symptoms—diarrhea, throat ulceration, ocular damage—align with Cyprian’s account, and its spread through military and urban networks is plausible. Yet Cyprian nowhere mentions the hallmark rash and pustules. Only the rare hemorrhagic form of smallpox produces the combination of bloody eyes, severe diarrhea, and ulcerated throats he describes. That form, however, was uncommon and typically left survivors scarred, another detail absent from his text.

Bubonic Plague

The disease caused by Yersinia pestis produces vomiting, fever, and limb pain. Its septicemic form brings diarrhea and internal bleeding, and the pneumonic form spreads person-to-person. But the most common sign of bubonic plague—the swollen, blackened buboes of groin and armpit—goes unmentioned by Cyprian. For him to describe continuous vomiting, diarrhea, and gangrene, yet omit such obvious swellings, weighs against this diagnosis.

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers

Diseases caused by viruses such as Lassa, Yellow Fever, Dengue, and Ebola all share a pattern of fever, hemorrhaging, diarrhea, and high mortality. Some, like Yellow Fever and Dengue, are mosquito-borne and less likely to have spread so widely in Roman Europe. Ebola, however, matches most of Cyprian’s details. It causes extreme fever, vomiting, diarrhea, conjunctival bleeding, tissue necrosis leading to limb loss, and sensory loss including blindness and deafness.

It also spreads through bodily fluids and even from the corpses of the dead—making the Christian care for victims and burials all the more striking, and dangerous. Unlike measles or smallpox, Ebola does not confer immunity, so cities could suffer repeated outbreaks.

When Cyprian’s symptom list is set against all proposed diseases, Ebola or a related viral hemorrhagic fever emerges as the best match. Its clinical picture aligns with his words, its contagion explains widespread fear of contact, and its persistence without immunity explains multiple waves across the empire. While no biomolecular evidence survives to prove the case, the fit between description and disease is striking.

The Legacy of the Plague

Exact numbers cannot be recovered, but ancient voices emphasize scale. Dionysius of Alexandria claimed that after the epidemic, the number of living between fourteen and eighty was smaller than the number aged forty to seventy before the plague.

Other reports claimed two thousand people died in a single day in Rome. (There are reports that claim 5000 people died every day) Modern parallels help estimate. In the 2013–2016 Ebola epidemic, mortality among the infected initially reached 70%, before falling closer to 40% with intervention. If the Cyprian Plague was similar, death rates among those infected could have been between 40–70%, though this would not mean the entire population was struck. More likely, pockets of high mortality devastated cities, villages, and armies, while other areas were spared.

The epidemic exposed deep tensions. Edicts required compulsory sacrifice to the gods, provoking Christian resistance. Christians, far from fleeing, were praised by their own leaders for nursing the sick and burying the dead—acts that may have increased mortality among them, yet also elevated their reputation. Pagan sacrifices, by contrast, were visibly ineffective. In a society where divine favor was expected to secure health, this failure undermined old rituals and gave Christianity credibility as a “religion of care.”

The cultural response echoes what is seen in later crises. Archaeology at Poggio Gramignano in Italy, for instance, shows pagan rituals reappearing during a later malaria outbreak, with puppy sacrifices and other rites to ward off evil. In the 3rd century, similar anxieties were channeled through compulsory sacrifices. Yet as the plague did not cease, the appeal of Christianity’s promise of eternal life grew stronger. ("A Plague in a Crisis: Differential Diagnosis of the Cyprian Plague and its Effects on the Roman Empire in the Third Century CE" by Amber Kearns)

While the evidence drawn from Cyprian, Dionysius, and the archaeological record already paints a vivid picture of the epidemic, further research has uncovered additional details that deepen our understanding of both its scale and its consequences. These findings bring into sharper focus how profoundly the plague shaped the empire’s demography, culture, and political order.

Rome’s Forgotten Pandemic

Research has revealed further dimensions of the Cyprian Plague that sharpen our sense of its scale and consequences. Records from Alexandria show that the epidemic began in Egypt around 249 CE and that the city’s population may have collapsed by more than sixty percent. This catastrophic demographic loss highlights the scale of devastation before the disease ever reached Carthage or Rome.

Some later testimonies also preserve details not found in Cyprian. One recalls the torment of extreme thirst, an additional symptom that reinforces the picture of a disease resembling a viral hemorrhagic fever. Reports also noted the epidemic’s seasonality: striking hardest in autumn and receding in summer, a pattern unlike smallpox or plague.

The archaeological record adds chilling confirmation. At Thebes in Egypt, lime kilns and pits were used for large-scale corpse incineration — rare, direct evidence of epidemic disposal in antiquity. In Rome, hurried burials in the catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter stacked over 1,300 skeletons in layers, a striking sign of mortality crisis.

The toll was staggering. Contemporary sources claimed up to 5,000 deaths in a single day in Rome, and observers insisted that entire cities were left emptied of inhabitants.

The plague also reverberated through politics, economy, and religion. The collapse of the silver-based currency system and its replacement with gold coincided with the epidemic. Military command shifted decisively to Danubian officers after senators were excluded from legionary leadership under Gallienus. Pagan philosophers lamented that traditional gods such as Asclepius had abandoned the cities, while the figure of Jesus was increasingly honored.

This climate of despair and religious reorientation helped accelerate Christianity’s expansion, as its communities provided care and hope where older cults seemed powerless. ("Pandemics and passages to late antiquity: rethinking the plague of c.249-270 described by Cyprian" by Kyle Harper)

The Plague of Cyprian was more than a medical mystery. It was a force that struck at the empire’s armies, emptied its cities, and unsettled its faith in the old gods. It left scars in the archaeological record, in the writings of bishops and philosophers, and —as aforementioned— in the coinage of emperors who turned to Apollo for deliverance.

Above all, it revealed the fragility of a world already in crisis. In the silence left by traditional rituals, Christianity’s promise of endurance and salvation found fertile ground, ensuring that this forgotten pandemic played a decisive role in reshaping the Roman world.

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: