Purple Pollution: How Rome’s Lust for Luxury Stained the Ancient Seas

Rome’s emperors wrapped themselves in purple, a color that signaled power and divinity. But beneath the gleam lay stinking vats, mountains of broken shells, and coastlines scarred by waste. The latest discoveries at Tel Shiqmona reveal the hidden cost of Rome’s most famous luxury.

Rome loved its symbols big and bold. Arches that swallowed avenues; forums that choreographed power in marble and shadow; colors that announced status before a word was spoken. Of those colors, none mattered more than purple. It was not a dye so much as a claim—on rank, on wealth, on the right to be seen.

In the Senate House, the broad stripe of the latus clavus carried the prosaic weight of law inside its narrow band. On the triumphal route, a general’s purple shimmered like a visible oath that Jupiter smiled upon Rome. Later, when emperors cocooned themselves in it, purple turned from accent into aura. Children born near the imperial porphyry were said to be “born in the purple,” as if the stone itself conferred legitimacy.

But prestige has a provenance; and prestige, in Rome’s case, smelled. Pliny the Elder, a meticulous gleaner of facts and gossip alike, praised the finest tone of the dye as “the colour of congealed blood, blackish at first glance but gleaming when held up to the light” (Natural History 9.135). No modern publicist could frame a luxury better. Then Pliny did the unthinkable and pulled back the curtain: those costly shells, he wrote, “have an unhealthy odour.” In two strokes, he gave us the whole economy of imperial glamour—radiance at a distance, rot at the source.

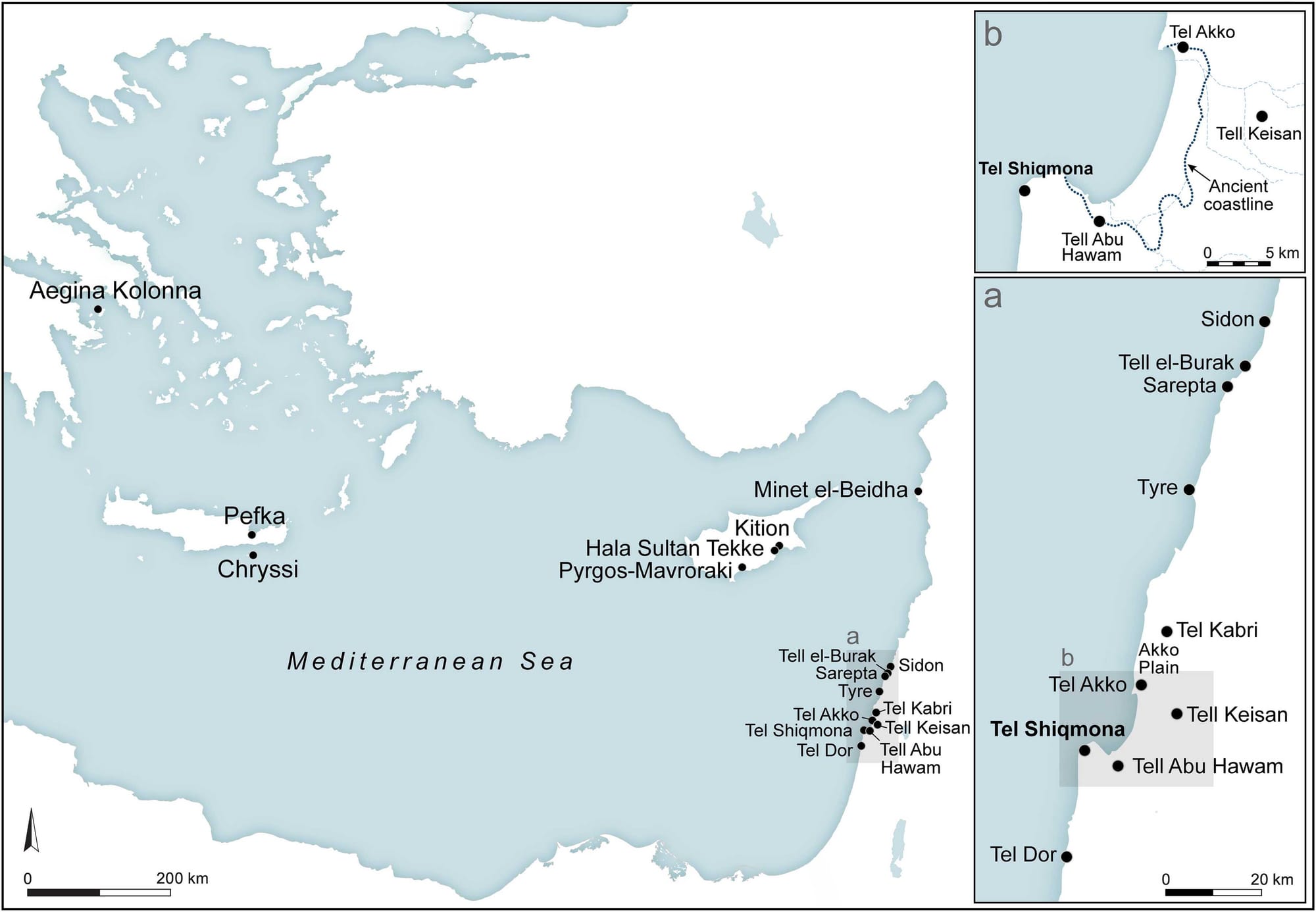

What recent archaeology has added is not a new metaphor but a floor plan. On Israel’s northern coast, at Tel Shiqmona, researchers have excavated the most telling site yet for the way purple was really made: a cluster of specialized installations, permanently stained by dye, used and reused across centuries.

The team’s plain-spoken summary lands with unusual force: Shiqmona is “a specialized facility for large-scale and long-term production (~1100–600 BCE) of the lucrative purple dye,” and “the first time that unequivocal large-scale production sustained for half a millennium is recognized in the Mediterranean” Before Rome, before the emperors’ wardrobes, before satire made Tyrian cloth a shorthand for excess, the industry that would drape the Empire was already humming here—stinking, staining, and reshaping a shoreline.

The Color of Empire—and Its Smell

Historians sometimes introduce purple as if it simply “became” the imperial color, a natural step in Rome’s escalator of spectacle. That’s tidy, but it flattens the labor and hides the waste. Purple took work: thousands of marine snails cracked in a specific way to free a tiny gland; fermentation in brine to coax out the precursor; controlled heating to turn the mess into miracle. Most of the animals involved never saw the light Rome later cast on them; they were wrenched from reefs, mangled, and dumped, their shredded shells rising in heaps that outlived their makers.

Roman writers knew the signal that purple sent. They rarely described the production, which by design stayed out of view. That is perhaps why Pliny’s pair of comments still sting: a line for the showroom, a line for the factory floor. The showroom line—“the colour of congealed blood”—makes the dye feel like destiny, the captured essence of victory itself. The factory-floor line—“unhealthy odour”—refuses to let the world forget what the essence costs. Both, together, tell us what purple really did in Rome: transform the labors and leavings of distant coasts into the bright shorthand of supremacy.

Rome codified that shorthand. Sumptuary habits—and eventually laws—fenced off purple for certain bodies and certain days. Senators wore a stripe, magistrates a broader mark, generals a cloak, and emperors the color entire. Restriction heightened desire; desire hardened the value; value justified restriction. The cycle fed on itself, like a myth of origins told over and over, more potent with each retelling. Yet beneath the theatre of scarcity, someone, somewhere, was boiling up the smell.

A Factory Before Factories

Enter Shiqmona. Long before textile mills made smoke a skyline feature, this low hill above the Carmel coast ran a quiet, pungent industry for centuries. The PLOS ONE team does not hedge: as aforementioned, the site can be “unequivocally… identified as a specialized facility for large-scale and long-term production (~1100–600 BCE) of the lucrative purple dye,” and it offers “the first time that unequivocal large-scale production sustained for half a millennium is recognized in the Mediterranean.” These aren’t superlatives for a press release; they are a sober rerouting of how we think about ancient economy.

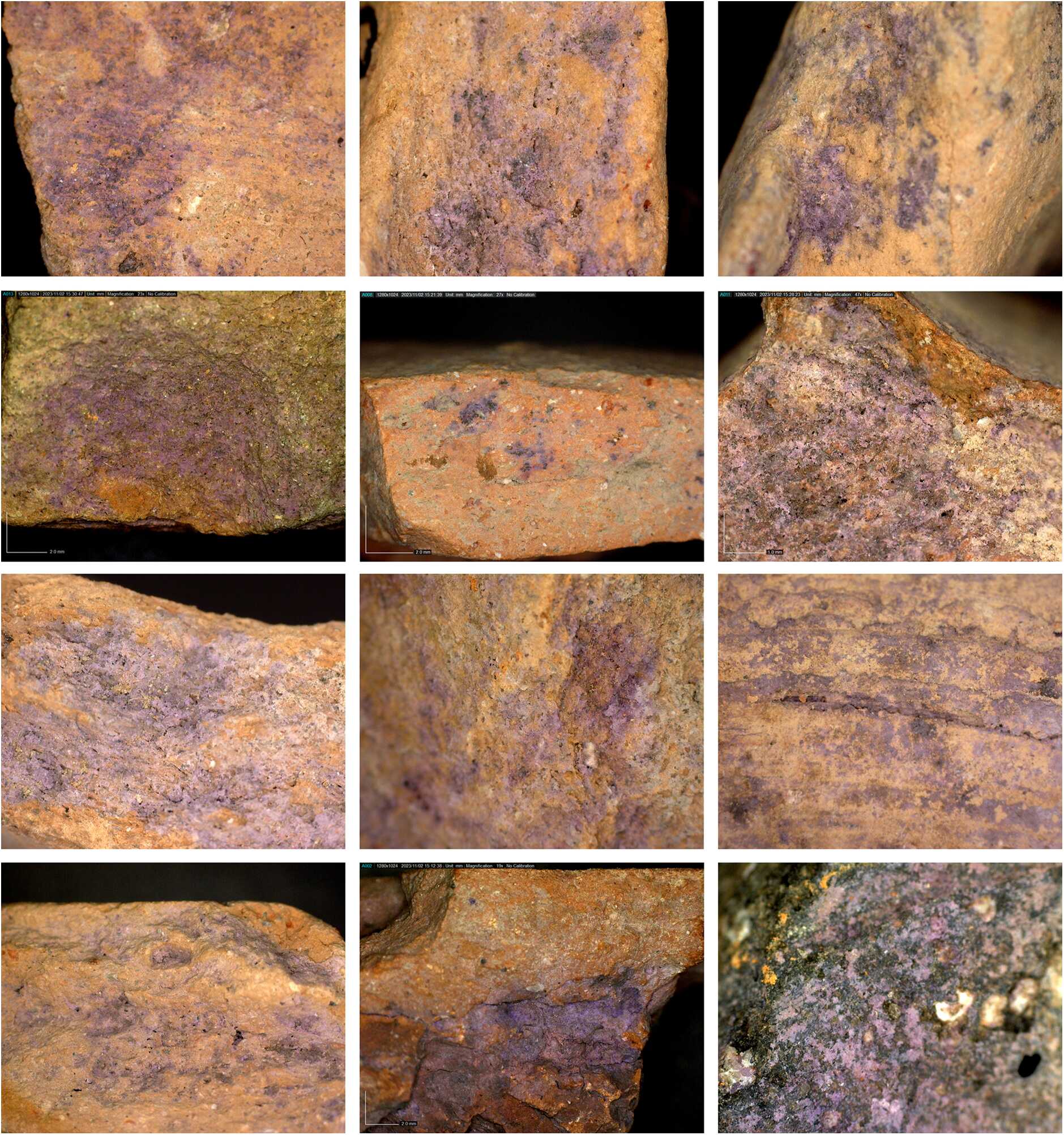

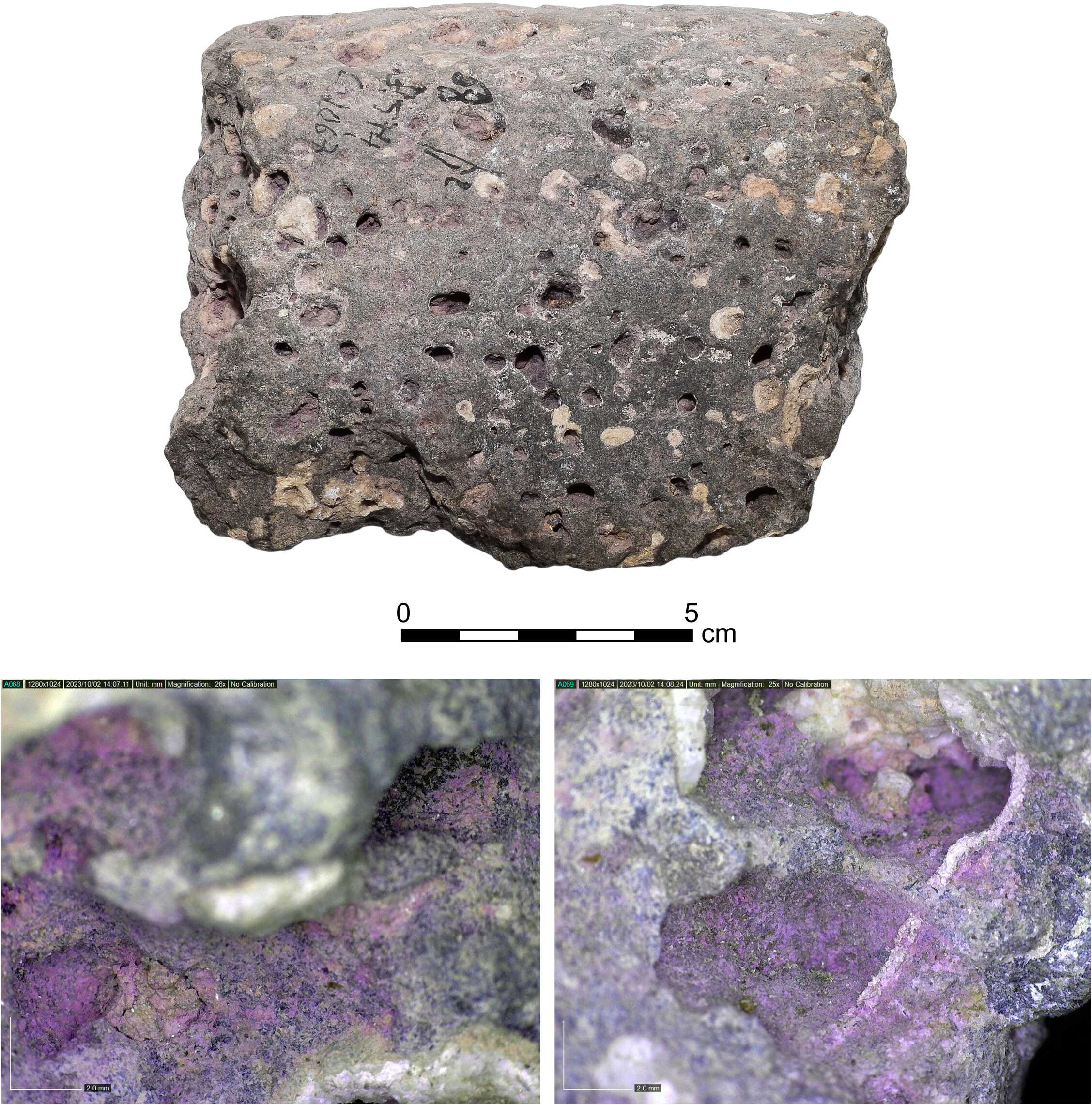

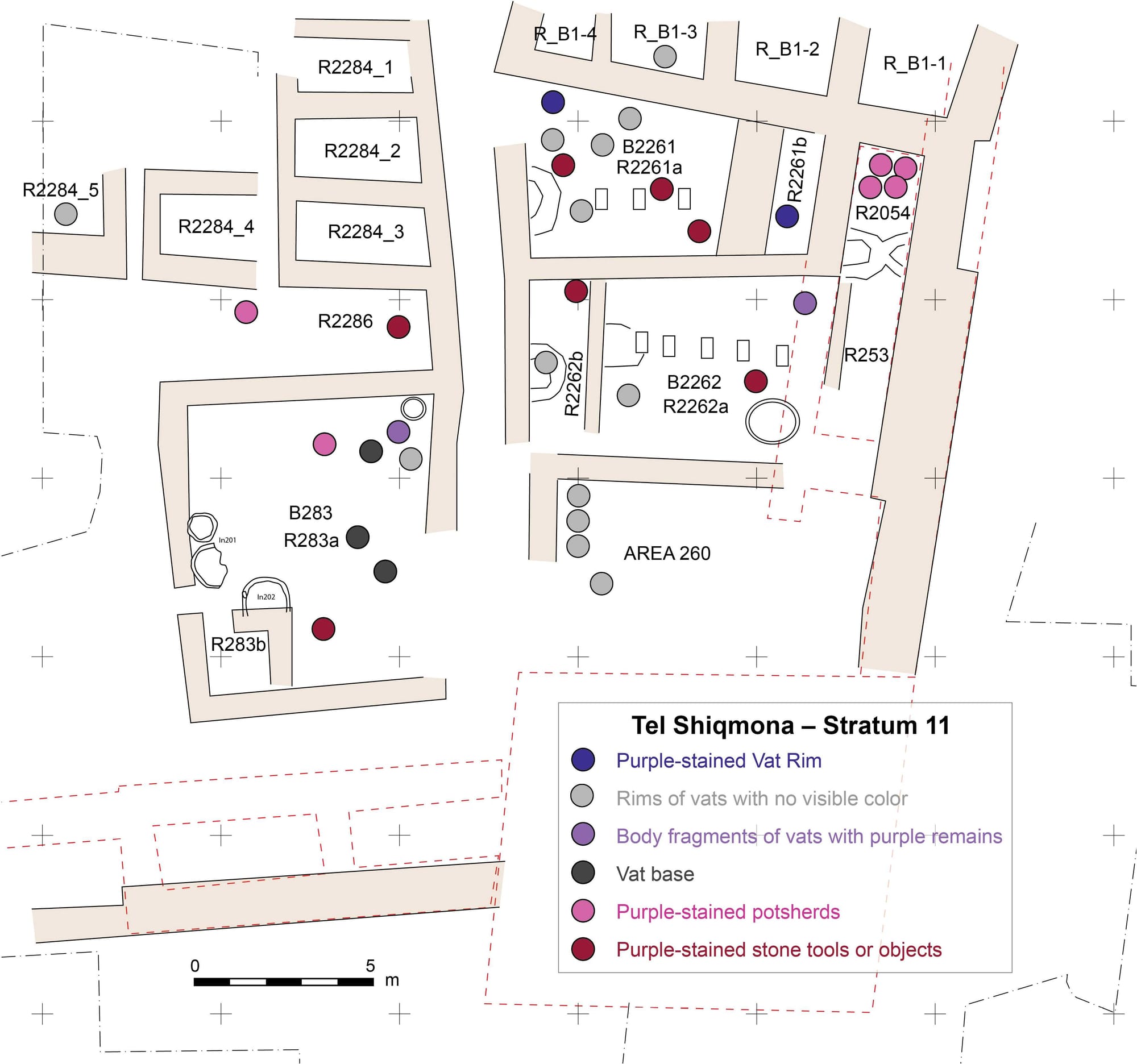

What do “large-scale and long-term” look like in the ground? Vessels with rims so saturated by purple that the color is still embedded in the fabric; distinctive heavy bases that match those rims; stone tools with dye ghosts on their broken faces; stained pebbles that served as hammers; and, crucially, a count.

In one layer alone, the team calculated a minimum number of at least sixteen vats; then they put a conservative bookend on use: “about 20 vats were active at some point during a phase lasting approximately 50 years.” Anyone who has ever toured an early modern manufactory will recognize the signatures—standardized kit, work surfaces marked by process, and a tempo of operation measured not in seasons but in generations.

The language we reach for—“proto-industrial,” “factory”—can feel anachronistic, but Shiqmona earns it. Between the eleventh and sixth centuries BCE, the installations here didn’t dabble in purple. They made it, again and again, until the places that made it became purple too. And that, in turn, feeds a larger truth about the world Rome inherited: when the city moved to the center of consumption, it did not invent a luxury; it conscripted one that already had its own geography, technology, and costs.

The Anatomy of a Dirty Miracle

There is a reason purple’s process rarely shows up in triumphal rhetoric. No one wanted to imagine a pearl of color inside a coil of glands. At Shiqmona, the archaeology refuses squeamishness. One of the most quietly devastating lines in the report sits in a list of tools:

“About 5% of the Iron Age stone artifacts at Shiqmona bear purple stains.”

Five percent is not a splatter here and there; it’s a workplace where the chemistry of prestige has soaked into the implements of labor. Hammers, grinding stones, bowls—the dye is on them all, not as ornament but as residue.

Ceramics tell an even tighter story. The team highlights “conspicuous rims with purple residues,” paired with “unique bases” that together define a powerful silhouette: the workhorse vat of the trade. They are, as the authors put it, “unparalleled uniform massive industrial vessels.” When you hold a rim and a base that match across contexts and decades, you aren’t holding a pot; you’re holding a system. Beneath the microscope, the chemistry cooperates:

“The HPLC analysis revealed that all 28 artifacts examined… were stained with ‘true’ purple dye produced from Muricidae species. All the samples contain at least one of the two molecules that are principal markers of this dye, namely MBI and DBI.”

The jargon hides a simple certainty—this is the real stuff, the dye that would become the Empire’s most talked-about color. And then there is the sentence that should sit above the door of any museum gallery that tries to make purple pretty:

“Large-scale purple dye manufacture was a messy business. Shiqmona clearly reveals that large-scale dye manufacturing and dyeing generated significant waste.”

A possible representation of a freshly painted Tyrian purple cloak. Credits: Roman Empire Times, Midjourney

You can feel the authors restraining themselves. The shells that gave up their glands did not dematerialize when the cloth left the coast. They piled up—smelly monuments to appetite. The brine that coaxed the molecules into life didn’t cease to exist when the tone was right. It soaked the ground. The vats didn’t wipe themselves clean for the next elite commission. They hardened into instruments whose very bodies testified to what they did.

The Luxury Economy as a Machine for Inequality

We are used to saying that luxury “signals status,” as if the signal were a neutral technical matter—power choosing a frequency and turning up the volume. Shiqmona invites a different lens. Luxury is also a machine, one that translates concentrated labor and concentrated waste into concentration of prestige.

In the Iron Age, that prestige attached to royalty and cult. Shiqmona’s authors open their study by stressing how purple sat at the apex of social and sacred dress from “the 2nd millennium BCE to the fall of Constantinople,” worn by “royalty, elites, and serving cultic purposes.” It was never common; it was never meant to be.

By the time Rome comes into view, the machine is merely scaled and formalized. The Republic and Empire don’t invent the exclusivity; they anthem it. Senatorial stripes, magistrates’ markings, the triumphal robe, and at last the emperor’s total claim—the ladder grows taller as it narrows. In sumptuary practice and then in edict, purple becomes a fence you can see.

On one side, the few who may wear it; on the other, the many who must live with its costs. Shiqmona visualizes that side of the fence. The people who fed the vats could not reap their social yield. The snails were local; the aura traveled.

Roman satire twitches with that tension, even when it doesn’t say so outright. The joke only works if everyone recognizes the code. That is why a throwaway Roman line about Tyrian cloth needs no explanation—the city was fluent in luxuries it would never touch. It understood that certain colors came freighted, like a seal on a letter you were not allowed to open.

Global Color: Networks Beneath the Shine

Shiqmona also clarifies a different kind of map. It’s tempting to tell the story of purple in Roman terms—Tyre and Sidon as glamorous brand names on a product the capital monopolized. The truth is both simpler and more interesting. Before Rome was Rome, there was a Levantine shoreline dotted with places like this one: skilled labor wrapped in standardized kit, local reefs harvested to feed distant wardrobes.

The dye itself was the hard-won prize of a niche ecological knowledge; the textiles were the vehicles of that knowledge through a sea of markets. Even Roman literature, which prefers the city as a stage for everything, preserves the foreignness of purple in its very nicknames. One poet teases a patron about garments “dyed twice in the shellfish blood of Tyre,” and the audience understands both the sneer and the cost. Another treats “Tyrian wraps” as a hallmark of people with more money than sense.

Under those lines are old routes and older habits: Phoenician sailors, Cypriot ports, Greek brokers, Italic buyers—all riding a current of color that began in places that smelled like work. By the imperial period, the current is deeper. Rome has the appetite and the administrative muscle to make scarcity an article of policy, and purple obliges, because its bottlenecks are built-in.

You can’t rush a gland; you can only crush more snails. You can’t fake the chemistry; you can only guard it. The more the city desires, the more coastlines are conscripted into making the desire visible. From Sidon to Carthage to Spain, the proof is the same: shell hills, stained soils, tools that forgot they were tools and became evidence.

From Sacred Cloth to State Skin

One of the most human things about purple is how it slid so easily between the language of gods and the language of government. The Shiqmona study notes what temples and offerings long suggested: in the Iron Age, dyed textiles belonged as much to ritual as to rank. A robe could make a body look more like a statue; a hanging could make an altar look more like a throne. When Rome absorbed the cultic grandeur of earlier Mediterranean worlds, it also absorbed the dye’s double life.

Triumph made the merger complete. A general in his purple stood at the axis where soldier, priest, and actor fused. The city watched him become a version of Jupiter’s favorite, briefly draped in a color that visually translated favor into fact. Later, emperors made the garment permanent, or pretended to. The robe that once marked a day became a skin that marked a dynasty. In Byzantium, purple chambers midwifed metaphors into birth certificates; dynastic prose turned a dye into a womb.

And yet—and always—the source remained what Pliny would recognize if he could walk the Carmel coast now and see the purple still inside the rims, again remembering his already mentioned passages: “The colour of congealed blood,” he’d mutter, approving the shade; “an unhealthy odour,” he’d add, wrinkling his nose. It is the paradox that made purple so useful to empires and so clarifying to archaeology: a thing holy and base at once, because human hands made it so.

Waste as Archive

If Shiqmona had yielded lovely fragments of cloth alone, we would have admired them and moved on. The site’s power lies in its refusal to curate away the costs. Vats do not lie, and neither do stains. The report’s line is not rhetorical but literal:

“Large-scale purple dye manufacture was a messy business. Shiqmona clearly reveals that large-scale dye manufacturing and dyeing generated significant waste.”

Waste is not a footnote here; it is a method. It allows a modern reader to stand inches from the residue of a process that ancient writers were happy to summarize but reluctant to display. The distribution of that residue lets us scale without romance:

“Counting MNI, the artifacts represent a minimum of 38 production vats from the Iron Age.”

“In Stratum 11… a MNI of 16 vats… about 20 vats were active… approximately 50 years.”

“About 5% of the Iron Age stone artifacts… bear purple stains.”

Each measure pushes us past the picturesque shell heap toward a recovered industrial landscape: not a one-off “factory” but a sustained way of making that turned years into work and work into marks.

And because Shiqmona is early, it forces us to widen the frame on Rome. The Empire’s taste did not invent the processes it loved. It concentrated them, regulated them, priced them, and—above all—wore them.

When triumphators stepped into the forum wrapped like divinity, they were wearing standardized vats, brined glands, stained tools, reef ecologies, and labor they would never smell. Whatever we mean by “globalization” in antiquity, Shiqmona gives it a texture: distant waste in the service of local shine.

What Purple Tells Us About Power

So much of Roman history, even at its most intimate, is about distance—between capital and province, between law and life, between spectacle and source. Purple collapses those distances into something you can hold and something you can see. Hold a Shiqmona rim and you are holding the same process that made a senator a senator at a glance. Watch a dyed stripe pass between colonnades and you are watching the afterlife of a reef.

It also returns an old moral vocabulary to its proper scale. “Luxury” in Roman invective often reads like a private sin with public consequences, a story about appetites unworthy of office. Shiqmona lets us flip the lens. Luxury is not just appetite; it is apparatus. It requires an infrastructure that makes appetite legible across space. It makes waste a constant and turns smell into the price of seeing.

Pliny tried to square the circle for his readers—“mad lust” on one side, “unhealthy odour” on the other—and he left us a neat pair of sentences to quote in perpetuity. The archaeology gives us the third line the ancient texts never wrote: this is where the smell lived, and this is how long it stayed.

The Carmel coast began it; Rome finished the story. The Empire’s most legible color, the densest symbol in its wardrobe, was born not just in glands or in myths, but in places like this one—places that were purple long before the cloth was.

Coda: The Stain That Lasts

The lesson that matters most for Roman history is simpler and older. Purple is what happens when a society invests meaning in a material so hard to make that the making becomes invisible. Shiqmona makes it visible again. It shows us vats with color trapped in their clay, tools with work etched into their breaks, and numbers that smell like scale. The site does not diminish Rome’s theatre; it adds a backstage and leaves the door ajar.

There is a temptation, when writing about Rome’s grandeur, to imagine that the grandeur has nothing to do with us. Shiqmona won’t allow it.

The paper pauses to note that along this same coastline today, mollusk communities have been “decimated… by global warming, salinization and pollution,” with some recovery in recent years where Muricidae remain relatively abundant. It is a sober reminder that seas have long carried the burden of our symbols, and still do. (Tel Shiqmona during the Iron Age: A first glimpse into an ancient Mediterranean purple dye ‘factory’, by Shalvi et al., 2025).

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: