The Remarkable Survival of Marcus Aurelius' Meditations: A Historical Overview

How have “Meditations” or better yet” To himself”, the thoughts of Marcus Aurelius survived through the centuries?

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, a collection of personal writings and reflections by the Roman Emperor, survived through a rather remarkable and somewhat serendipitous process of transmission over the centuries.

Marcus Aurelius, the Stoic Roman Emperor who reigned from 161 to 180 AD, penned a series of personal notes and reflections that would later be known as the "Meditations." These writings, deeply introspective and philosophical, were possibly never intended for public consumption. Yet, they have survived the ravages of time, wars, and the decay of empires to become one of the most revered philosophical texts in history.

How did this intimate diary of a Roman Emperor endure through the ages? Let's delve into the fascinating journey of the "Meditations" from the hands of Marcus Aurelius to the bookshelves of modern readers.

We don’t know what became of Marcus’ private writings immediately following his death. It is likely that, since these writings were composed during the latter part of his life while on campaign, they, along with his other personal belongings, were brought back to Rome. It’s possible they were placed in the imperial library there.

Clearly, some effort was made to preserve them.

A representation of the Roman Imperial Library, where Meditations survived for eons. Illustration: Midjourney

A happy —and lucky— young man

The future Marcus Aurelius, who would later take this name following his adoption by Emperor Antoninus Pius, was born in Rome in 121 under the name Marcus Annius Verus. His parents’ families owned several brick factories, which generated enormous wealth and required significant capital investment. This wealth provided them with considerable political influence, allowing factory owners like Marcus Aurelius’ grandfather to play a role in influencing construction projects.

After his grandfather’s death during Marcus’ early childhood, the young Marcus came under the notice and protection of Emperor Hadrian, who favored him. In 138, just before his death, Hadrian, seeking to secure the succession, adopted Antoninus Pius, who was Marcus’ uncle by marriage, and instructed him to adopt both Marcus and Lucius Verus, the son of Aelius Caesar, Hadrian’s original choice for successor who had recently died.

When Hadrian passed away on July 10, 138, Antoninus Pius succeeded him. A year later, at the age of eighteen, Marcus was elevated to the position of Caesar. In 145, he married Faustina, the daughter of Antoninus. The couple had thirteen children, but only six survived beyond childhood: five daughters and one son, the future Emperor Commodus. (The inner citadel: The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius by Pierre Hadot)

The journey of Marcus’ thoughts

The "Meditations" were written during Marcus Aurelius' military campaigns against the Germanic tribes. They served as a personal journal, a source of guidance, and a means to practice Stoic philosophy. Written in Greek, the text is divided into 12 books, each filled with concise aphorisms and reflections on virtue, duty, death, and the nature of existence.

Initial Preservation

The earliest direct mention of Marcus Aurelius’ writings comes from Themistius (nicknamed Euphrades — Εὐφραδής in Greek, meaning "eloquent"), a statesman, rhetorician and philosopher) who wrote in the fourth century AD.

In his Orations, Themistius, who studied and served as a senator and later as prefect in Constantinople, likely read Meditations there, possibly in the relocated imperial library, and referred to Marcus’ Admonitions (parangelmata).

It’s also plausible that Emperor Julian, a contemporary of Themistius and a fellow philosopher, might have read Meditations in Constantinople. Given Julian’s intellectual pursuits, it’s reasonable to think he would have taken an interest in Marcus’ writings if he was aware of them. In a letter to Themistius, Julian expressed his admiration for Marcus’ “perfect virtue” (teleia aretē) and his doubts about matching such an example.

By this time, Constantinople was becoming the main center for the Roman emperors, and much of the Imperial library from Rome might have been moved there. The fact that the earliest references to Marcus’ writings come from Constantinople suggests that his notes had made their way eastward.

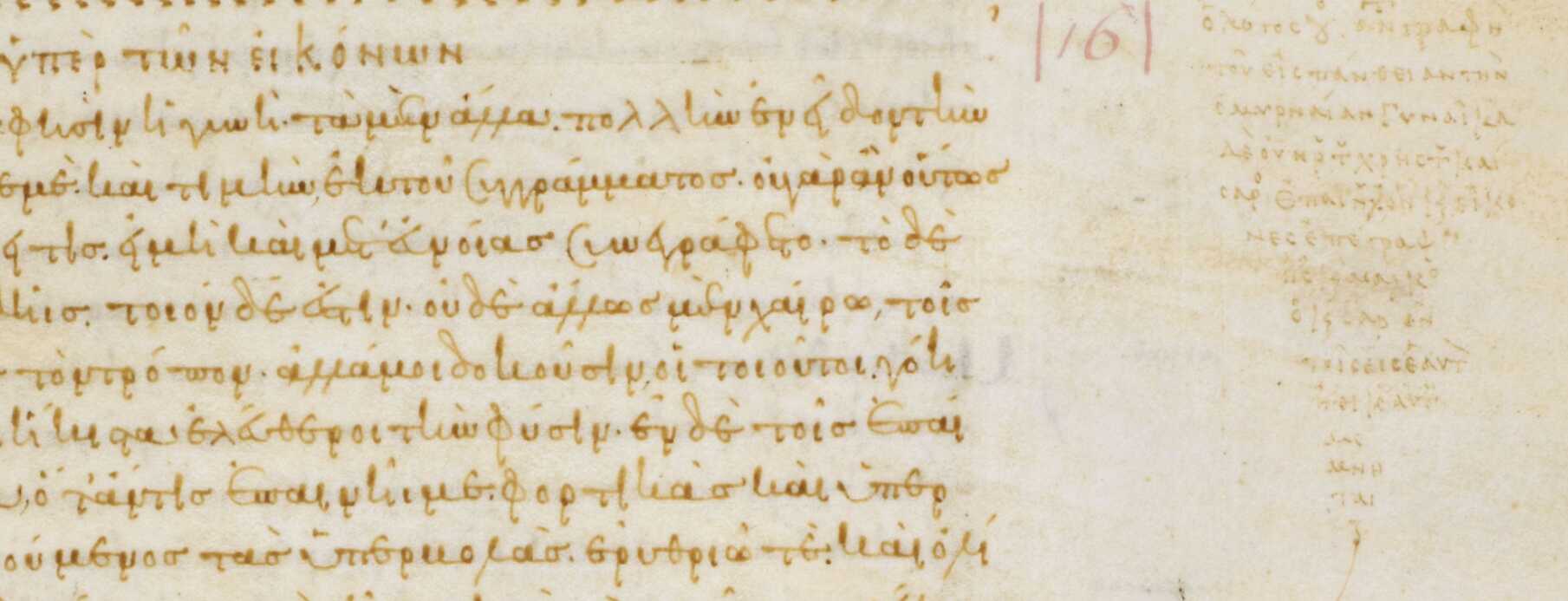

The Byzantine Era and Arethas of Caesarea

The next solid evidence of Meditations is found in the works of Arethas, Archbishop of Caesarea, who mentioned owning a copy around 900 AD. Arethas had a new copy made and sent the original to a friend, Demetrius. He also referred to Marcus’ work by the title To Himself (Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτὸν — ta eis heauton), marking the first use of what has become the standard Greek title of the work.

Although Meditations didn’t circulate widely, it remained accessible to some readers in the Byzantine world. The tenth-century Suda lexicon quotes it multiple times, noting it as a work in twelve books. In the thirteenth century, Maximos Planudes (a Byzantine Greek monk, scholar, anthologist, translator, mathematician, grammarian and theologian at Constantinople), produced an edition of selections from Meditations.

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Joseph Bryennius (a learned Byzantine monk of the 15th century and a monk at the Monastery of Stoudios), also quoted from Meditations several times, though he did not name the source. Some selections of excerpts, possibly derived from Planudes’ edition, circulated in fifteenth-century Italy.

However, Marcus Aurelius did not prominently feature in the Renaissance revival of Greek philosophical literature. While Marcus the emperor was respected through the works of Cassius Dio and the Historia Augusta, Meditations remained largely unknown.

Public domain

An homage to Arethas of Caesarea, pictured seated at a wooden table, surrounded by scrolls, with a large ancient tome open before him, reading intently under the warm candlelight.

Illustration by DALL-E

Rediscovery in the Renaissance

There was one notable exception: the German humanist Johann Reuchlin (1455-1522), known for his expertise in Greek and Hebrew. Reuchlin was familiar with Meditations and quoted from it in both his published works and letters. In his De verbo mirifico (1494), he translated five passages from Meditations into Latin without citing the source.

He also referenced Marcus in letters to contemporaries like Erasmus, using the title Ad se ipsum well before it appeared in print in the editio princeps. One idea that particularly caught Reuchlin’s attention was the phrase “simplify yourself,” which he quoted again in his later work De arte cabalistica (1517).

However, Reuchlin did not seem to view Meditations as a Stoic work but rather as a collection of ancient wise sayings.

A portrait of Johannes Reuchlin. Credits: Europeana, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Libro aureo

Aside from Reuchlin, it appears that no one else was reading Meditations in the early sixteenth century. However, Marcus Aurelius became something of a bestseller due to the Libro aureo de Marco Aurelio, first published in Spanish in 1528 and quickly translated into all major European languages.

This book was written by Antonio de Guevara, a courtier who later became a monk. Guevara claimed that his work was based on a Greek manuscript, but no evidence of such a manuscript has ever been found. He also suggested that he didn’t know Greek and relied on unnamed friends to translate the manuscript into Latin, which he then translated into Spanish.

The Libro aureo blends biographical details, such as the Antonine plague, with fictional letters and imaginary dialogues, like those between Marcus and his wife. The first edition was printed without Guevara’s knowledge from an unfinished manuscript, prompting him to release a more complete, authorized version the following year titled Libro del emperador Marco Aurelio con relox de principes.

Both versions were rapidly translated into French, Italian, and English, and reprinted multiple times. Although Guevara’s work had little connection to Meditations, it helped to shape the broader image of Marcus as a source of worldly wisdom and an ideal philosopher-prince. (Chapter:The early modern reception of the Meditations, by John Sellars)

The first printed edition

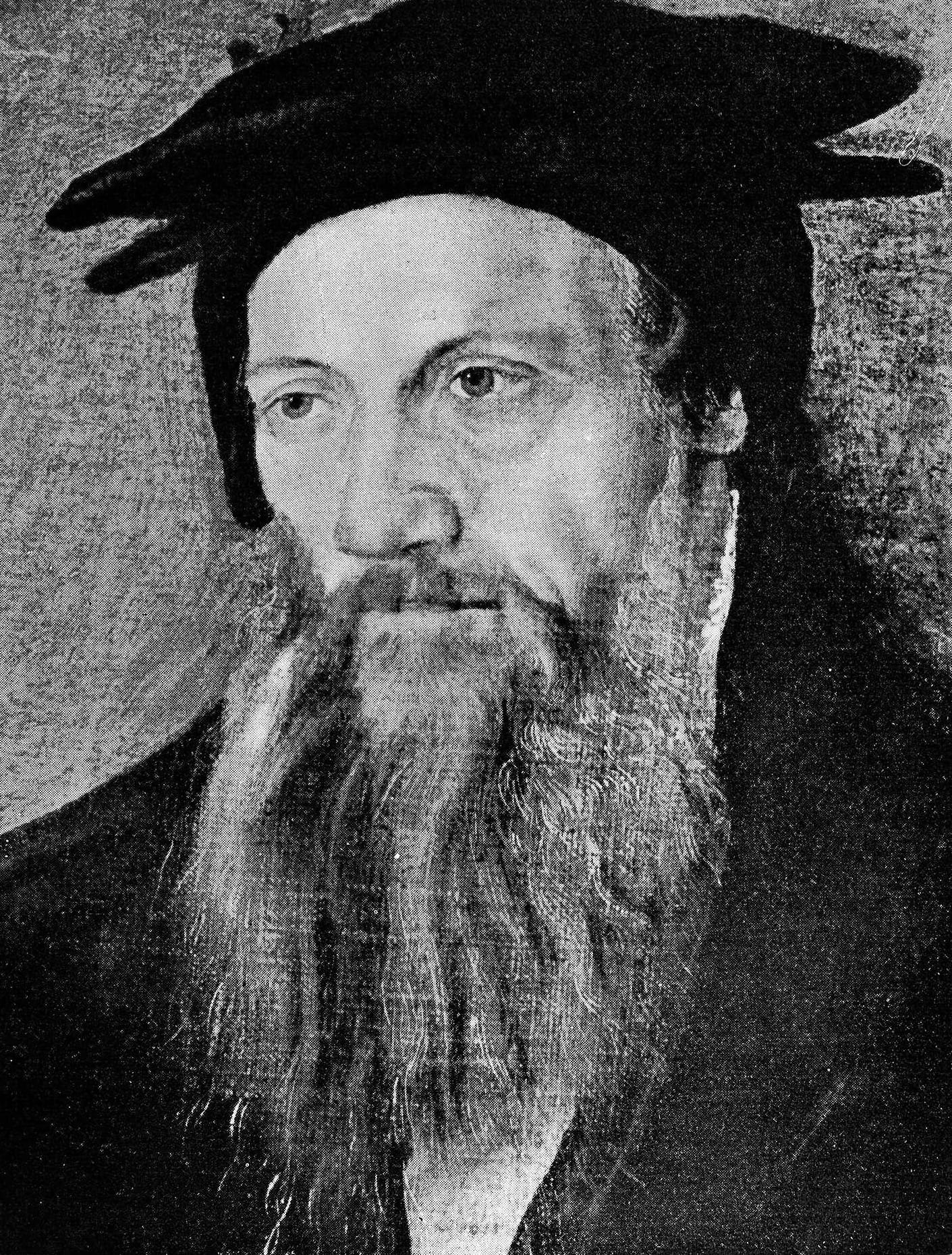

The Meditations were first printed relatively late, in 1559. This initial edition was overseen by the esteemed humanist Conrad Gesner, who based it on a manuscript from the Palatine library in Heidelberg, where he served as librarian.

Unfortunately, the manuscript itself has since been lost, which is not uncommon for first printings of classical texts.

Portrait of Conrad Gesner by Tobias Stimmer, CC BY 4.0

During the typesetting process, the manuscript pages were often taken apart and subsequently destroyed. Gesner enlisted Wilhelm Holtzmann, who Latinized his name to ‘Xylander,’ to prepare a Latin translation of the text, and it is under this name that the first edition of the Meditations is typically recognized.

This first edition sparked some interest, leading Xylander to make corrections for a second edition printed in 1568, with another reprint following in 1590. However, the Meditations did not seem to make a significant impact at the time. As many have observed, the Meditations did not become a prominent Stoic text in the handbooks of Stoic philosophy compiled by Justus Lipsius, which were printed in 1604.

- One reason for this might be that Lipsius primarily focused on elucidating Seneca’s works, and since Marcus wrote after Seneca, his writings were not considered relevant to Lipsius’ goals.

- Another reason could be how the Meditations were presented in Xylander’s edition. The title De vita sua (On His Own Life) might have led readers to mistakenly assume the work was an autobiography, especially if they began reading with Book 1.

In fact, there was little in the original edition to suggest that the Meditations was a work rooted in Stoic philosophy.

What are the “Meditations?”

Meditations is a unique philosophical work in which Marcus Aurelius reflects on a variety of philosophical topics and personal challenges. Unlike other philosophical texts from Antiquity, Meditations is a collection of notebook entries that were likely never meant for public distribution.

Except for Book 1, which focuses on the people who influenced Marcus’s life, the remaining eleven books consist of philosophical and personal reflections that are arranged without any particular order or clear structure. Although Marcus does not always explicitly state his philosophical positions or the reasoning behind them, it is evident from the text and other sources, like his correspondence with his rhetoric tutor Fronto, that Marcus was deeply committed to Stoicism.

Meditations includes numerous instances of Marcus grappling with everyday problems through the lens of Stoic ethics, physics, and logic. Despite frequently quoting Plato and using some Platonic terminology, Marcus’s philosophical outlook is fundamentally Stoic.

He often cites the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, acknowledging him as a significant influence, and he also quotes Heraclitus, whose concept of nature as an eternal fire had a strong impact on Stoic physics.

Challenges to Preservation

The journey of the "Meditations" was not without challenges. Wars, invasions, and the sacking of libraries threatened the survival of many ancient texts. The "Meditations" survived due to a combination of factors: its recognition as a philosophical masterpiece, the efforts of scholars and translators, and a degree of fortuitous luck.

The exact means by which Meditations was preserved after Marcus’s death and through the Middle Ages is unclear, and the text did not gain significant readership until its first printed edition in the 16th century. Since then, it has become especially popular among general readers, though less so among professional philosophers.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, figures like Henry More, the Third Earl of Shaftesbury, and Francis Hutcheson were enthusiastic readers of Marcus. More recently, Meditations has greatly influenced Pierre Hadot’s interpretation of philosophy as a way of life, which in turn impacted the later work of Michel Foucault. (Marcus Aurelius, by John Sellars)

The first connection to Stoicism

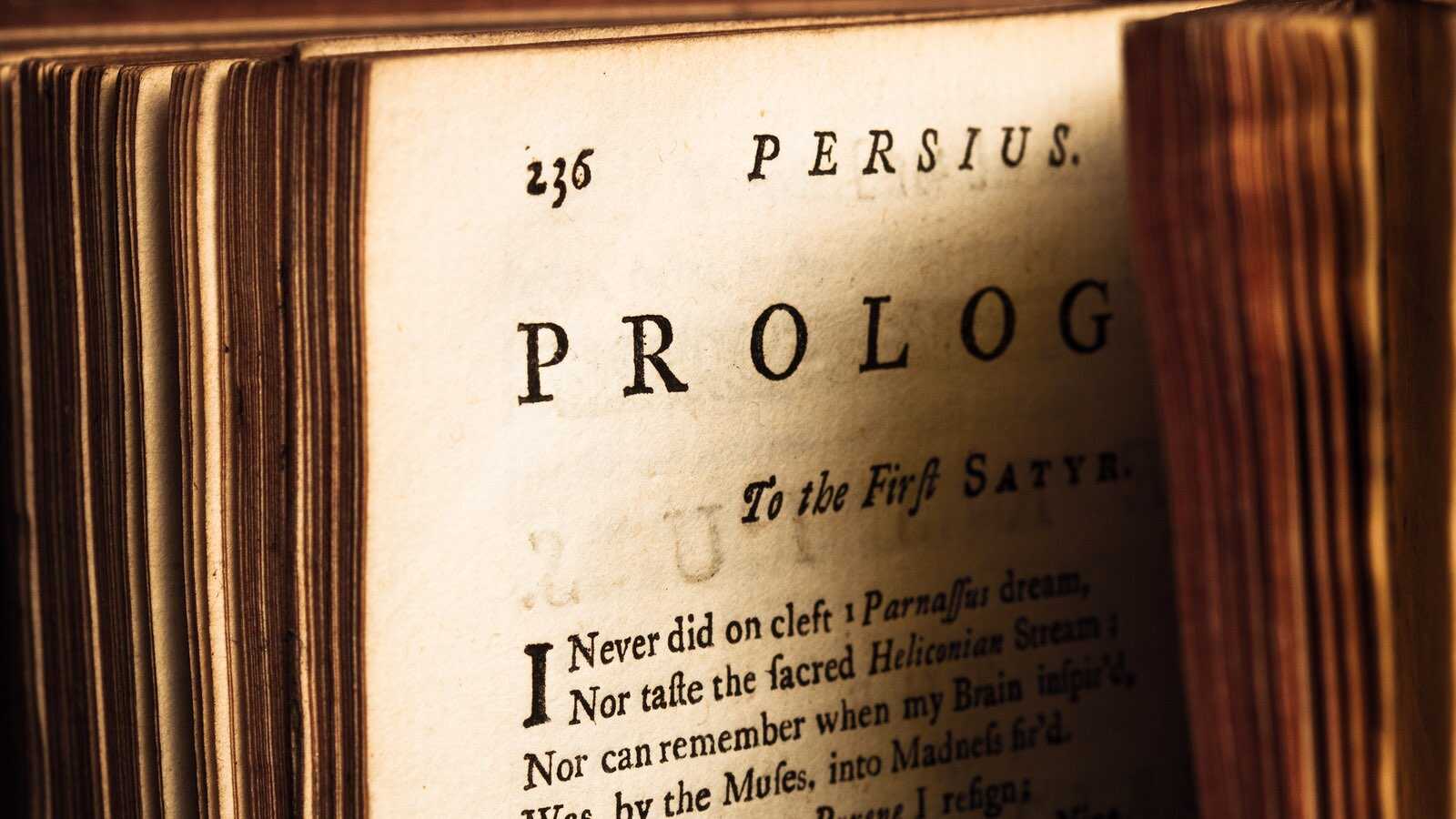

Isaac Casaubon, (a classical scholar and philologist), appears to be the first person to extensively use the Meditations and explicitly connect the work with Stoicism.

In 1603, Casaubon edited the Scriptores Historia Augusta, a collection of biographies of Roman emperors, which includes a biography of Marcus Aurelius traditionally attributed to Julius Capitolinus. In his commentary on Marcus’ biography, Casaubon frequently quoted the Meditations, particularly material from Book 1 that discusses figures in Marcus’ life mentioned in the ancient biography.

Two years later, in 1605, Casaubon published an edition of the Satires by the Stoic poet Persius, accompanied by a substantial commentary—23 pages of Persius’ text were met with 522 pages of Casaubon’s analysis.

Central to his interpretative approach was emphasizing Persius’ use of Stoic ideas, and his commentary is therefore rich with discussions of Stoic doctrine, supported by quotations from various Stoic sources. In this context, Casaubon often cited the Meditations, demonstrating his deep familiarity with the text.

For instance, in Persius’ first satire, which mentions praise, Casaubon connects this to the Stoic doctrine of ‘indifferents’ (adiaphora), referencing Diogenes Laertius, Cicero, Galen, and Seneca, and culminating with a quotation from Meditations: “In any case, what is it to be remembered forever? Nothing but vanity.”

Similarly, in the second satire, where Persius refers to a “soul steeped in nobleness and honour”, Casaubon interprets this in light of Stoic themes, citing doxographical material from Plutarch and Lactantius alongside Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, specifically Meditations: “an athlete contending for the greatest of all prizes (that of never being thrown by passion), deep-dyed in justice.”

When Persius mentions a “sleepless and close-cropped youth” drawn to Stoic doctrines, Casaubon references Meditations, where Marcus reflects on his own youthful asceticism as a student of Stoicism.

In these instances, and many others, Casaubon uses the Meditations as a key source for Stoic doctrine, presenting Marcus Aurelius—whom he calls “sapientissimus” (the wisest)—as a prime example of a Stoic.

Standardisation of the text of Meditations

Thomas Gataker’s edition of Meditations, published in 1652 nearly a decade after Casaubon’s edition, was a significant work that had been in development for some time. Printed in Cambridge with the help of influential friends, Gataker’s edition often referenced Casaubon’s work, indicating that he continued refining his manuscript long after their encounter.

This edition is notable for several reasons. It included an extensive commentary that is still highly regarded, and it introduced a new method of dividing the text, which has become the standard.

However, the most important aspect of Gataker’s edition was its interpretive focus, which sought to highlight the similarities between Stoicism and Christianity.

A gravure of Marcus Aurelius, and a golden Christian cross. Illustration: Midjourney

Gataker argued that the Stoics, more than any other ancient philosophical school, emphasized piety and virtue, aligning closely with Christian principles. He also made a clear distinction between Stoicism and Cynicism and strongly criticized Epicureanism, dedicating much of his introduction to cautioning against its moral risks.

Gataker admired the Stoics for their belief in a providentially ordered universe and their teachings on accepting this order with grace, loving others, and acting virtuously.

He considered the works of Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius to be the highest expressions of Stoic philosophy, noting their close alignment with Christian values. Gataker emphasized that Meditations provides practical guidance on how to live out these virtues in everyday life, making it a valuable supplement to the Gospels.

Gataker’s commentary continued this interpretation, drawing many parallels between Meditations and Biblical teachings and elaborating on Stoic ideas with references to a wide range of ancient sources. Both Gataker and Casaubon aimed to show that Meditations is a Stoic philosophical work that aligns with Gospel teachings and offers practical advice that can benefit Christian readers, despite being written by a non-Christian.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

The enduring appeal of the "Meditations" lies in its universal themes and timeless wisdom. From Renaissance scholars to modern-day readers, the text's reflections on resilience, virtue, and the transient nature of life have found a receptive audience. Today, the "Meditations" is not just a historical artifact but a source of inspiration for people from all walks of life. Its teachings have influenced leaders, writers, and thinkers, solidifying its place as one of the most impactful philosophical works ever written.

The survival of Marcus Aurelius' "Meditations" is a testament to the enduring power of profound thought. From the battlefields of Germania to the libraries of Byzantium, from the scholarly pursuits of the Renaissance to the digital pages of modern e-readers, the "Meditations" has traversed centuries and continents.

Its journey, marked by the efforts of individuals like Arethas of Caesarea, is a remarkable tale of preservation, rediscovery, and enduring relevance. As we reflect on its history, we are reminded of the timeless nature of wisdom and the enduring human quest for understanding.

Meditations, as John Sellar writes in his book Marcus Aurelius, travelled through the centuries being treated differently by its admirers and followers and each one of them added, explained, analysed and cross-referenced something new to what we know of the book today.

Even if Marcus just kept an imperial diary and never meant to let his thoughts meet the eyes of the public, even if he was just writing down things for himself to remember to be a better human, we can consider ourselves extremely lucky and blessed to be able to read what this extraordinary mind has put into words and what scholars have collected into a book.

Let us not forget, that this individual who speaks of piety, modesty, patience and virtue, was a Roman Emperor during the Empire’s height; quite possibly the most powerful person to live the Earth, at the time. Instead of enjoying a myriad pleasures or satisfying his personal ego, he wrote a personal diary of sorts, that today inspires millions, and some claim is more important and influential than religious books, like the Bible.

When you start to lose your temper, remember: There’s nothing manly about rage. It’s courtesy and kindness that define a human being-and a man.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations Book 11

About the Roman Empire Times

See all the latest news for the Roman Empire, ancient Roman historical facts, anecdotes from Roman Times and stories from the Empire at romanempiretimes.com. Contact our newsroom to report an update or send your story, photos and videos. Follow RET on Google News, Flipboard and subscribe here to our daily email.

Follow the Roman Empire Times on social media: